Never before had so many Roman troops faced each other on a

single battlefield. Never before had two of Rome’s greatest generals fought it

out like this. Pompey, conqueror of the East, fifty-seven, a former young

achiever who had made history in his twenties, a multimillionaire, an excellent

military organizer, a master strategist, coming off a victory, with the larger

army. Caesar, conqueror of the West, who had celebrated his fifty-second

birthday only three weeks before in the month that would eventually bear his

name, who had been nearly forty before he made his first military mark, an

original tactician and engineering genius with a mastery of detail, a commander

with dash, the common touch, luck, and the smaller but more experienced army.

Plutarch was to lament that, combined, two such famous,

talented Roman generals and their seventy thousand men could have conquered the

old enemy Parthia for Rome, could have marched unassailed all the way to India.

Instead, here they were, bent on destroying each other.

It probably occurred to Centurion Crastinus that he might

know some of the 1st Legion centurions across the field, might have served with

them, might have drunk with them and played dice with them somewhere on his

legionary travels. He would have watched them talking to their men, animatedly

passing on instructions. They were easy enough to spot; like him, they wore a

transverse crest on their helmets. It made them easy to identify for their own

men, and marked them as targets for the opposition. Centurions were the key to

an army’s success in battle. Crastinus knew it, and Caesar knew it. The 10th

Legion’s six tribunes were back between the lines. Young, rich, spoiled members

of the Equestrian Order, few had the respect of the enlisted men. From later

events it is likely that one of the 10th’s tribunes, Gaius Avienus, had done

nothing but complain since they set sail from Brindisi that Caesar had forced

him to leave all his servants behind.

This day would be decided by the centurions and their

legionaries, the rank and file, and as Crastinus had told Caesar, he was

determined to acquit himself honorably. Four hundred fifty yards away, men of

the first rank of the 1st Legion would have been looking at Crastinus and

setting their sights on making a trophy of his crested helmet. The man who took

that to his tribune after the battle, preferably with Crastinus’s severed head

still in it, could expect a handsome reward. Without doubt they looked confident,

these legionaries of the 1st. Crastinus may have imagined they thought they

were something special, Pompey’s pets. Crastinus would see how confident they

looked in an hour or so.

Around the centurion, his men would have been becoming

impatient, knowing in their bones that this day would not be like the others

when they’d stood and stared at their opponents for hours on end before

marching back to camp at sunset. This day the air was electric, and the tension

would have been getting to some of them, wanting to move, to get started.

As if in answer, trumpets sounded behind the ranks across

the field. Many of Pompey’s men were more than nervous; the centurions of the

newer units were having trouble maintaining their formations, so Pompey decided

not to waste any time. Moments before, the thousands of cavalry horses banked

up on the extreme left of Pompey’s line had been waiting restlessly, some

neighing, some pawing the ground, some fidgeting and hard to control. Now, with

a cacophony of war cries, their riders were urging them forward. Within

seconds, seven thousand horses and riders were charging across the wheat field.

Behind Crastinus, trumpets of his own side sounded. In

response, Caesar’s German and Gallic cavalry lurched forward to meet the Pompeian

charge, with their auxiliary light infantry companions running after them. The

Battle of Pharsalus had begun.

On Pompey’s side, his thirty-six hundred archers and

slingers dashed out from behind the lines and formed up in the open to the rear

of their charging cavalry. On command, the bowmen let loose volleys of arrows

that flew over the heads of their galloping troopers and dropped among Caesar’s

charging cavalry.

The infantry of both sides remained where they were in their

battle lines, and watched with morbid fascination as their cavalry came

together on the eastern side of the battlefield. General Labienus would have

been at the head of his German and Gallic cavalry, cutting down any Caesarian

trooper who ventured near him, and issuing a stream of orders.

For a short while Caesar’s cavalry held its ground, but with

their men falling in increasing numbers, they began to give way. At least two

hundred of Caesar’s cavalrymen were soon dead or seriously wounded, and

Labienus saw the time had come to execute the maneuver that Pompey had planned.

Leaving the allied cavalry to deal with Caesar’s troopers, probably under the

direction of his colleague General Marcus Petreius, he led his German and

Gallic cavalry around the perimeter of the fighting and charged toward the

exposed flank and rear of the 10th Legion.

Caesarian auxiliaries scattered from the path of the

cavalry, and the men of the 10th Legion on the extreme right were forced to

swing around and defend themselves as Labienus’s troopers surged up to them. As

Labienus urged more squadrons to ride around behind the 10th and as they came

to the legion’s third line, Caesar, not many yards away, barked an order.

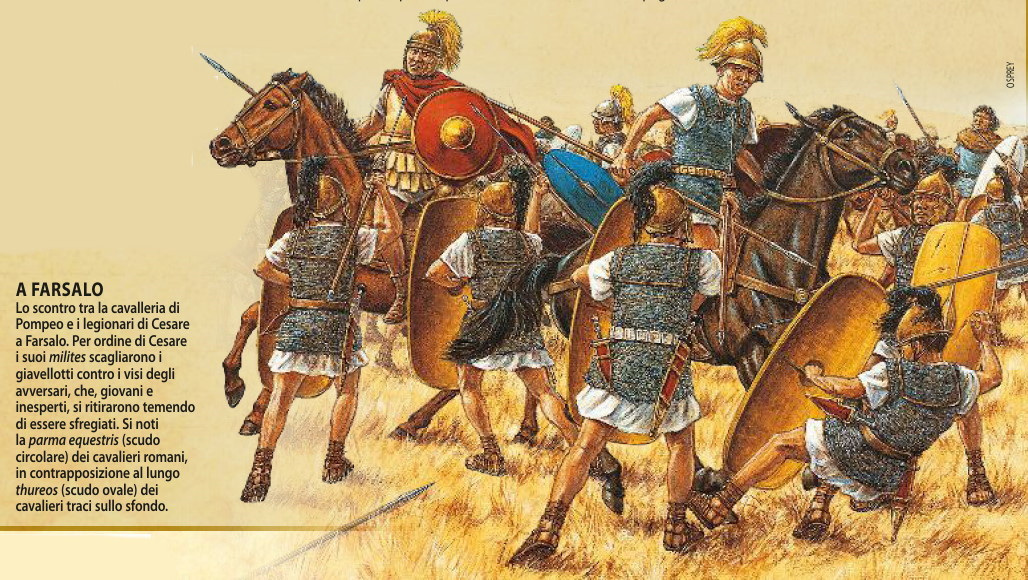

Trumpets sounded, and the reserve cohorts of the fourth line

suddenly jumped to their feet and dashed forward behind their standards,

slamming into the unsuspecting cavalrymen before they even saw them. The men of

the reserve cohorts had been given explicit instructions not to throw their

javelins but to use them instead like spears, thrusting them overarm up into

the faces of the cavalrymen. According to Plutarch, Caesar said, when issuing

the order for the tactic, “Those fine young dancers won’t endure the steel

shining in their eyes. They’ll fly to save their handsome faces.”

Now Caesar’s shock troops mingled with the surprised Germans

and Gauls at close quarters, pumping their javelins as instructed, taking out

eyes, causing horrific facial injuries and fatalities with every strike. The

congested cavalry had come to a dead stop, compressed between the rear ranks of

the 10th and the reserve cohorts. There were so many of them there was nowhere

for the riders to go; they merely provided sitting targets for the men of the

reserve cohorts as they swarmed among them.

As many as a thousand of Labienus’s best cavalrymen were

killed in this counterstroke. The panic that was created quickly spread to the

allied cavalrymen behind them. Seeing the carnage, with Labienus’s big,

longhaired riders falling like ninepins or reeling back and trying to protect

their faces from the javelin thrusts instead of pressing home the now stalled

attack, the allied riders disengaged from Caesar’s cavalry, turned, and

galloped from the battlefield, heading in terror for the hills.

This allowed Caesar’s cavalry to join the reserve cohorts

against Labienus’s men, and despite the general’s best efforts to rally his

troopers, the combination of infantry and cavalry was too much for them and

they broke and followed the allied cavalry toward the high country. Labienus

had no choice but to pursue his own men, with hopes of trying to regroup.

As Caesar’s cavalry chased Labienus and his troopers all the

way to the hills, Pompey’s left flank was exposed. With a cheer, Caesar’s

reserve cohorts spontaneously rushed forward to the attack in the wake of their

victory over the cavalry. All that stood in their way were Pompey’s archers and

slingers. These men of Caesar’s strategic reserve, high on their bloody success

against the mounted troops, quickly crossed the ground separating the two

groups, neutralizing the effectiveness of the archers’ arrows and the slingers’

lead shot. The slingers were armed merely with their slingshots. The archers,

men from Crete, Pontus, Syria, and other eastern states, were armed, apart from

their bows and arrows, only with swords. In close-quarters combat they were no

competition for legionaries whose specialty was infighting. As the slingers

ran, the archers bravely stood their ground and tried to put up a fight, but

they were soon mowed down like hay before the scythe.

Now Caesar issued another order. His red banner dropped. The

trumpets of the first and second infantry lines sounded “Charge.”

In the very front rank, on the right of Caesar’s line,

Centurion Crastinus raised his right hand, clutching a javelin now. Caesar

would later be told of his words. “Come on, men of my cohort, follow me!” he

bellowed. “And give your general the service you have promised!”

With that, he dashed forward. All around him, the men of

Caesar’s front line roared a battle cry and leaped forward, javelins raised in

their right hands for an overarm throw when the order came to let fly.

Ahead, to the surprise of Crastinus and his comrades,

Pompey’s front line didn’t budge. Pompey’s men were under orders to stand still

and receive Caesar’s infantry charge, instead of themselves charging at

Caesar’s running men, as was the norm in battles of the day. According to

Caesar, this tactic had been suggested to Pompey by Gaius Triarius, one of his

naval commanders. Pompey, lacking confidence in his infantry and anxious to

give them an edge in the contest, had grabbed at the idea, which was intended

to make Caesar’s troops run twice as far as usual and so arrive out of breath

at the Pompeian line.

Caesar was later scathing of the tactic. He was to write

that the running charge fired men’s enthusiasm for battle, and that generals

ought to encourage this, not repress it. In fact, Pompey’s tactic did have

something going for it, as his troops would present a solid barrier of

interlocked shields against Caesar’s puffing, disorderly men, who had to break

formation to run to the attack. It may have been effective against

inexperienced troops, but in the middle of the battlefield Centurion Crastinus

and his fellow centurions of the first rank drew their charging cohorts to a

halt. The entire charge came to a stop. For perhaps a minute the Caesarian

troops paused in the middle of the wheat field, catching their breath; then,

led by Crastinus, they resumed the charge with a mighty roar.

On the run, the front line let fly with their javelins. At

the same time, in Pompey’s front line, centurions called an order: “Loose!” The

men of Pompey’s front line launched their own javelins with all their might,

then raised their shields high to receive the Caesarian volley. Then, with

javelins hanging from many a shield, they brought them down again, locking them

together just in time to receive the charge. With an almighty crash Caesar’s

front line washed onto the wall of Pompeian shields. Despite the impact of the

charge, Pompey’s line held firm.

Now, standing toe to toe with their adversaries, Caesar’s

men tried to hack a way through the shield line. On Caesar’s right wing,

Centurion Crastinus, repulsed in his initial charge, was moving from cohort to

cohort as his men tried to break through the immovable 1st Legion line, urging

on his legionaries at the top of his voice above the din of battle. Crastinus

threw himself at the shield line, aiming to show his men how to reach over the

top of an enemy shield and strike at the face of the soldier on the other side

with the point of his sword. As he did, he felt a blow to the side of the head.

He never even saw it coming. The strength suddenly drained from his legs. He

sagged to his knees. His head was spinning. Dazed, he continued to call out to

his men to spur them on.

As he spoke, a legionary of the 1st Legion directly opposite

him in the shield line moved his shield six inches to the left, opening a small

gap. In a flash he had shoved his sword through the gap with a powerful forward

thrust that entered the yelling Gaius Crastinus’s open mouth. According to

Plutarch, the tip of the blade emerged from the back of Crastinus’s neck. The

soldier of the 1st withdrew his bloodied sword and swiftly resealed the gap in

the shield line. His action had lasted just seconds. No doubt with a crude

cheer from the nearby men of the 1st Legion, Centurion Crastinus toppled

forward into the shield in front of him, then slid to the ground.

It was a stalemate at the front line. Neither side was

making any forward progress. But on Caesar’s right, the reserve cohorts, fresh

from the massacre of Pompey’s archers and slingers, were swinging onto the

flank and rear of the 1st Legion.

Pompey had seen his cavalry stroke destroyed in minutes, had

seen the cavalry he’d been depending on for victory flee the field. And now his

ever-dependable 1st Legion was in difficulty. If the 1st couldn’t hold, no one

could. Without a word, he turned his horse around and galloped back toward the

camp on the hill. A handful of startled staff rode after him.

Plutarch says that as Pompey reached the camp’s praetorian

gate, looking pale and dazed, he called to the centurions in charge, “Defend

the camp strenuously if there should be any reverse in the battle. I’m going to

check the guard on the other gates.”

Instead of going around the other three gates of the camp as

he’d said, he went straight to his headquarters tent, and there he remained. He

hadn’t wanted this battle, he had known the likely outcome, especially if it

came down to a pure infantry engagement. But expecting something and then

actually experiencing it are two different things. In a military career spanning

thirty-four years Pompey the Great had never once experienced a defeat. And

never once, in all probability, had he put himself in the shoes of men he’d

defeated, and imagined what defeat might feel like. It would have made the

emptiness of failure all the more difficult to comprehend.

The men of the 1st, fighting now on three sides and

outnumbered, were in danger of being surrounded and cut to pieces. No orders

came from Pompey—he’d disappeared. None came from their divisional commander,

the useless General Domitius. Pompey had failed to maintain a reserve, which

might have been thrown into support the 1st now in its time of need. With no

hope of reinforcement, and with self-preservation in mind, the officers of the

1st decided to make a gradual withdrawal, in battle order, in an attempt to

overcome the threat to their rear. Orders rang out, trumpets sang, and

standards inclined toward the rear. Their pride and their discipline intact,

the 1st Legion began to pull back in perfect order, step by step, harried all

the way by the 10th Legion and the reserve cohorts.

Beside the 1st, the 15th Legion did likewise. Away over on

Pompey’s right, General Lentulus, seeing the left wing withdrawing, and with

his own auxiliaries and slingers already in full flight, ordered his

legionaries to emulate the 1st Legion and make an ordered withdrawal, for if

they attempted to hold their ground, the center would give way and the right

wing would be pressed against the Enipeus and surrounded. Like their comrades

of the 1st, the Spanish veterans of the 4th and 6th Legions maintained their

formation as they slowly edged back, pressed by their countrymen of the 8th and

9th. But in the center, the inexperienced youths of the three new Italian

legions began to waver. They tried to follow the example of the legions on the

flanks, but their formations, like their discipline, began to break down.

Now Caesar issued another order. Again his red banner

dropped. Again trumpets sounded “Charge.” Now the men of his third line, who

had been standing, waiting impatiently to join the fray, rushed forward with a

cheer. As the fresh troops of the third line arrived on the scene, the men of

the first and second lines gave way and let them through. The impact of this

second charge shattered what cohesion remained in Pompey’s center. Raw recruits

threw down their shields, turned, and fled toward the camp on the hill they’d

left that morning. Auxiliaries did the same, and the entire center dissolved.

It was barely midday, and the battle was already lost to Pompey’s side. It was

now just a matter of who lived, and who died, before the last blows were

struck.

The 1st Legion stubbornly refused to break, continuing to

fight as it backpedaled across the plain pursued by the men of the 10th Legion

and reserve cohorts. The 15th Legion appears to have broken at this point, with

its men turning and heading for the hills. Over by the Enipeus, General

Lentulus deserted his men and galloped for the camp on the hill. The 4th and

6th Legions, cut off from the rest of the army, withdrew in good order,

fighting all the way, following the riverbank, which ensured they couldn’t be

outflanked on their right. Mark Antony pursued them with the 7th, 8th, and 9th,

and, apparently, with a charge was able to separate two cohorts of the 6th from

their comrades. Surrounded, these men of the 6th, a little under a thousand of

them, resisted for a time, then accepted Antony’s offer of surrender terms.

Meanwhile, two cohorts of the 6th and three of the 4th

continued to escape upriver, with their eagles intact. Antony would later break

off the pursuit and link up with Caesar at Pompey’s camp. These five cohorts of

Pompey’s Spanish troops later found a ford in the river, slid down the bank,

crossed the waterway, then struggled up the far bank. That night they would

occupy a village full of terrified Greeks west of the river before continuing their

flight west the next day.

At the camp on the hill, several thousand more experienced

legionaries of the 15th, the Gemina, and the two legions from Syria had been

regrouped by their tribunes and centurions to make a stand outside the walls.

But as tens of thousands of Pompey’s newer troops and auxiliaries swamped

around them, a number without arms, their standard-bearers having cast away

their standards, and with Caesar’s legions on their heels, they abandoned their

position and withdrew to make a stand on more favorable ground in the hills.

Behind them, many of the men flooding through the gates began looting their own

camp. It seems that the camp’s commander, General Afranius, had already escaped

by this time, spiriting away Pompey’s son Gnaeus, probably as prearranged with

Pompey.

While Pompey’s guard cohorts and their auxiliary supporters

from Thrace and Thessaly put up a spirited defense of the camp, the

overwhelming numbers of the attackers forced them to gradually withdraw from

the walls. With fighting going on inside the camp, young General Marcus

Favonius found Pompey in his headquarters tent. A friend of Marcus Brutus and

an admirer of Cato the Younger, Favonius, who’d been serving on Scipio’s staff

and just been made a major general, was a fervent supporter of Pompey. Now,

horrified by the state in which he found his hero, the young general tried to

rouse his commander from his stupor. “General, the enemy are in the camp! You

must fly!”

Pompey looked at him oddly. All authorities agree on Pompey’s

words at the news: “What! Into the very camp?”

Favonius and Pompey’s chief secretary, Philip, a Greek

freedman, helped their commander to his feet, removed their general’s

identifying scarlet cloak, replacing it with a plain one, then ushered him to the

door. Five horses were waiting outside the tent. According to Plutarch, three

of the four men who accompanied Pompey as he galloped from a rear gate before

Caesar’s troops could reach it were General Favonius; General Lentulus,

commander of the right-wing division; and General Publius Lentulus Spinther.

The fourth man would have been Pompey’s secretary, Philip.

The five riders galloped north toward the town of Larisa,

whose people were sympathetic toward Pompey. On the road, they encountered a

group of thirty cavalrymen. As Pompey’s generals drew their swords to defend

their leader they recognized the cavalry as one of Labienus’s squadrons,

intact, unscathed, and lost. With the troopers gladly joining their commander

to provide a meager bodyguard, the thirty-five riders hurried on.

Many of the men who had found a temporary haven in the camp

now burst out and fled toward Mount Dogandzis, where a number of their

colleagues were already digging in. The 1st Legion, in the meantime, appears to

have withdrawn east. With Caesar summoning the 10th Legion to help him in the

last stages of the battle at the camp, the 1st was able to continue to make its

escape. It appears to have swung around to the south in the night and then,

substantially intact and complete with most of its standards, including its

eagle, marched west to the coast and Pompey’s anchored fleet.

Leaving General Sulla in charge of the continuing fight at

the camp, Caesar regrouped four legions, his veteran 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th,

and set off after Pompey’s men who had fled to the mountain. Upward of twenty

thousand in number, mostly armed, and well officered still, these Pompeians

continued to pose a threat. As scouts reported that these survivors had now

left the mountain and were withdrawing across the foothills toward Larisa,

Caesar determined to cut them off before they reached the town and its

supplies.

Caesar took a shortcut that after a march of six miles

brought his four legions around into the path of the escaping troops in the

late afternoon. He formed up his men into a battle line. Seeing this, the

Pompeians halted on a hill. There was a river running along the bottom of the

hill, and Caesar had his weary troops build a long entrenchment line on the

hillside above the river, to deprive the other side of water. Observing this,

the men on the hill, all exhausted, hungry, and thirsty, and not a few wounded,

sent down a deputation to discuss surrender terms. Caesar sent the deputation

back up the hill with the message that he was willing to accept only an

unconditional surrender. He then prepared to spend the night in the open.