The OSS Special Operations and Operational Groups teams were

involved in supporting the Maquis of Vercors during one of the best-known and

much discussed episodes of the French Resistance during World War II. Vercors

is a plateau situated in the pre-Alps region between the cities of Valence and

Grenoble, about one hundred miles south of Lyon. Thirty miles long from north

to south and twelve miles wide east to west, Vercors is a formidable natural

fortress. To get inside it, an enemy had to go through an outer ring of

obstacles formed by the rivers Isère, Drôme, and Drar. Next, he had to cross

mountain ranges up to six thousand feet high that formed a perimeter over one

hundred miles long around the plateau. At that time only eight roads led into

Vercors, each of them with hairpin turns and narrow passes carved into the

sides of the mountain that a defender could easily keep under surveillance,

control, and if necessary destroy to prevent the advance of the enemy.

After the Franco-German armistice of June 25, 1940, Vercors

remained in the area of France controlled by the Vichy government, although the

Germans controlled Grenoble, the main city at the northern entrance of the

plateau. Being at the boundary of German-occupied zone and due to the

remoteness of its geography, Vercors became a place of refuge for people on the

run, including political refugees, French Jews escaping arrest, and former

French soldiers who did not want to serve under the Vichy regime. The plateau

came under the influence of the movement Franc Tireurs, founded in Lyon in 1941

and one of several resistance organizations that arose in France at the time.

Franc Tireurs, or “free shooters,” was a term used in France since the early

1800s to indicate irregular soldiers who fought behind enemy lines. In Vercors,

their actions began with publishing and distributing leaflets against the Vichy

policies and inciting passive resistance to the government directives.

The decision of Hitler and Mussolini to occupy the south of

France after the Allied landings in North Africa on November 10, 1942, caused

an influx of men to the Maquis of Vercors. The majority of them took to the

mountains to evade the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO), or Compulsory Work

Service, the mandatory labor service instituted in France that sent hundreds of

thousands of Frenchmen to work in Germany. The newly arrived were young, the

majority between nineteen and twenty-three years of age, and without any combat

experience. They came from all walks of life, had varied motivations, and were

affiliated with movements across the French political spectrum. Some attempts

to homogenize the members of the Maquis were made by equipes volantes, or

roaming teams of political agitators, who were mostly socialist-leaning members

of the Franc Tireurs movement interested in keeping other resistance factions

from establishing a following in Vercors. The military preparation of the new

arrivals was limited to studying a manual on guerrilla warfare assembled from

instructions on the use of irregular troops issued by the French Ministry of

Defense before the war. They also underwent physical training despite the

winter conditions and the fact that most of them wore city clothes not

appropriate for life in the mountains.

By the end of winter 1942–1943, four to five hundred members

of the Maquis had settled in a dozen camps around Vercors. Their main

preoccupation at the time was to secure provisions, including bread, meat, and

tobacco. Most of the veterans remembered the time in these camps as mostly

spent in boredom, filled with the drudgery of fetching water, collecting

firewood, and pulling kitchen duty. They launched some raids to secure arms and

munitions, but those remained marginal and most of the actions were against

Italian depots to secure provisions. Here is how Gilbert François remembered

the life in one of the camps:

When it was sunny, you could see a small flock being taken

to pasture in the morning and back to the stables in the evening, men lying in

the shade, others toasting in the sun, in other words, a vacation colony for

unemployed youth. This is what a solitary traveler would have seen venturing in

that abandoned landscape. We did water duty, vegetable cleaning duty, cutting

down trees, killing and preparing animals; and then there were alerts, raids in

Jossaud [the nearby village], and so on.

As long as the Maquisards remained in their camps and

limited their actions to raids on supply depots, the Italians were happy to

confine their actions to the discovery and collection of arms and ammunition

dumps hidden in caves around the area. Occasional hits against Italian soldiers

triggered raids on the Maquis camps or nearby villages, but no reprisals

against civilians ever occurred. Both sides had developed an unspoken mutual

warning system to signal each other’s presence and avoid head-on confrontations.

For example, on March 18, 1943, two hundred Italian soldiers left Grenoble

headed toward a Maquis camp. They sang all the way to ensure that there was no

surprise whatsoever in their arrival. The outcome of the operation was four

Maquisards arrested. One of the leaders of the Maquis of Vercors, Eugène

Samuel, later wrote that this relaxed behavior of the Italian army created bad

habits among the Resistance members. When the Germans took the place of the

Italians, the Maquisards learned the hard way to be more disciplined and paid

the price whenever they displayed reckless temerity.

The fight against the Maquis was primarily the

responsibility of the Fascist secret police, the Organization for Vigilance and

Repression of Anti-Fascism. Using a network of informers in the area, OVRA was

able to arrest the original founders of the Maquis, which left the movement

leaderless for a while and severed its connections with other Resistance groups

in France and the Free French in London and Algiers.

At the end of June 1943, a new generation of leaders stepped

up to reorganize the Maquis of Vercors. They embraced a strategic plan, known

as Plan Montagnards, or Highlanders Plan, that envisioned two ways in which the

Maquis could engage the Germans. In the first one, “Vercors would serve as a

center of unrest and refuge for guerrilla fighters who, at the opportune

moment, would attack railways, roads, bridges, electrical lines, and industrial

plants in the area. The area would be a launching point for incursions in the

rear of the German armies only at the time when they began their withdrawal

from the Rhône valley.” The second option, the most audacious one, envisioned

“the transformation of the plateau of Vercors into an aircraft carrier docked

on dry land.” Under this option, the main task of the Maquisards would be to

clear and prepare areas where Allied airplanes and parachutists could land.

The leaders of Vercors found a way to brief the French

leaders in Algiers about Plan Montagnards. They received the response over the

airwaves when the BBC broadcast the message “Les montagnards doivent continuer

a gravir les cimes,” or “The highlanders should continue to climb the summits.”

It meant that the plan was approved. No further instructions arrived to

indicate which of the two options was seen as more favorable, although during a

clandestine visit in Vercors, a senior French officer from Algiers made it

clear that “without artillery, or mortars as a minimum, there is no hope to

hold the plateau for long” in the event of an attack.

After the fall of Mussolini on July 25, 1943, and the

signing of the armistice between Italy and the Allies on September 8, Vercors

came under the 157th Reserve Division of the Wehrmacht, a unit created in

November 1939 in Munich from local recruits from Bavaria. It had been located

in southeast France since the fall of 1942 and did not have the combat

experience that had hardened other German troops, such as deployments in the

Eastern Front or in the Balkans. The division was under the commanded of

General Karl Pflaum, a career officer of the German military establishment

since 1910. Pflaum, born in 1890, had become a captain in 1921 and a colonel in

1937. He became general in 1941 and commanded the 258th Infantry Division in

the battles for Moscow between October 1941 and January 1942.

The Germans replaced OVRA with the Gestapo and the Milice

Française, or French Militia, the dreaded paramilitary force of the Vichy

regime. Known simply as the Milice, the French Resistance feared it even more

than the Gestapo and the SS for its ruthlessness and cruelty. The Gestapo and

the Milice quickly showed that they would not tolerate any acts of defiance in

the area. On November 11, 1943, when two thousand men marched to the monument

of the fallen in Grenoble to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the

French victory in 1918, Gestapo and French police surrounded them and deported

four hundred marchers to Buchenwald. The resistance responded by sabotaging

railroad and electricity lines, killing Milice members, and blowing up a depot

with two hundred tons of artillery munitions.

The Germans countered with Operation Grenoble, executed

between November 25 and 30, during which they arrested, killed, or deported

most of the resistance leaders in the area. It became known as the “bloody

week” or the Saint Bartholomew Massacre of Grenoble. On January 22, 1944, about

three hundred Germans responded strongly to a strike by the Maquis two days

earlier that had blocked one of the gorges leading into Vercors. The Germans

easily broke through their positions and moved in the village of

Chapelle-en-Vercors, forty miles south of Grenoble, where they burned down half

of the houses in reprisal. On January 29, the Germans attacked the Maquis at

Malleval, thirty miles south of Lyon on the opposite side of the plateau. A

French survivor of that engagement recalled later how the inexperienced

Maquisards had fallen into a lethal trap while advancing single file to meet

the enemy. A well-positioned machine gun opened up on them. About thirty

Maquisards died and only five or six were able to escape the massacre. The

Germans burned the village to the ground.

It became clear to the Maquis leaders that the numerous

camps where the Maquisards had spent the winter had become targets for the

Germans and created a great risk for the civilians around them who kept these

camps provisioned. A vast difference of opinions existed on whether it was best

to reinforce these camps with heavy weapons that the Allies would send or to abandon

them. Although all the Resistance military groups had been unified since

February 1, 1944, under the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), reaching a

consensus on the best way forward was very hard. Reflecting on the fate of the

Maquis groups recently attacked, the FFI commander for Vercors, Albert

Chambonnet, known as Didier, advised all Maquisards to “not engage in frontal

battles. Be flexible, fall back, and conduct guerrilla actions without mercy

against the flanks of the enemy.” At the end of March, Didier ordered the camps

abandoned and the men spread around Vercors in what he called “a state of

dispersed defense.”

In early January 1944, the Maquis of Vercors came into

contact with the Union mission, the first inter-allied team to be sent to France

as a precursor to the Jedburgh teams that would follow after the invasion

began. The team was led by British Colonel H. A. A. Thackthwaite and included

American Captain Peter J. Ortiz of the OSS and the French radio operator André

Foucault. The team parachuted on the night of January 6–7, 1944, near St.

Nazaire-en-Royans, in the outskirts of the Vercors plateau, halfway between

Valence and Grenoble. Within a few weeks, they had established contacts with

the military leaders of the area from the French-Italian border to Lyon and

impressed upon them that the main task of the Maquis at the time was to prepare

for guerrilla activities on or after D-Day.

Mission Union spend considerable amount of time in Vercors,

which had the widest concentration of Maquisards in the area. They advised the

French leaders to adopt a mobile defense, which meant letting the Germans move

freely by day and attacking their flanks and rear by night. They reported to

the Special Forces Headquarters in England that there was the potential to

mobilize up to three thousand Maquisards in Vercors; five hundred men were

already active and lightly armed. There were many former French military among

the Maquisards, with experience and training in the use of heavy arms, who

could form strong fighting groups if supplied with mortars, machine guns, and

other heavy weapons. When Mission Union returned to England at the end of May,

they prepared detailed accounts of their activities and were debriefed for

days. “Vercors has a very finely organized army,” they wrote, “but their

supplies, though plentiful, are not what they need; they need long distance

weapons and antitank weapons.”

The Allies had developed elaborate plans to activate all the

resistance networks and Maquis groups in France in a general national

insurrection against the Germans to coincide with the landings in the Normandy

beaches on D-Day. On June 1, 1944, at 1330 hours, the BBC began broadcasting

one hundred and sixty so-called personal messages, which were in effect code

words alerting their groups throughout France to prepare for action. The

messages were repeated at 1430, 1730, and 2115 hours of that day and then again

at the same times on June 2. Then, there was nothing on June 3, 4, and during

the day on June 5. Finally, at 2115 hours on June 5, the BBC broadcast for

sixteen minutes the code words for action directed at the twelve regional

organizations of the French Forces of the Interior and sixty-one Resistance

circuits controlled by the Allied Special Forces Headquarters.

The code words for the Maquis of Vercors were “Le chamois

des Alpes bondit,” or “The goat of the Alps leaps.” Those for the Drôme

department in which the lower half of the Vercors resides were “Dans la forêt

verte est un grand arbre,” or “There is a great tree in the green forest.” The

military and political leaders of the Resistance received these calls to action

with enthusiasm, believing that the moment had arrived to execute the Plan

Montagnards, mobilize the population, and close Vercors to the Germans. They

believed that “Vercors is the only Maquis in the whole of France, which has

been given the mission to set up its own free territory. It will receive the

arms, ammunition, and troops which will allow it to be the advance guard of a landing

in Provence. It is not impossible that de Gaulle himself will land here to make

his first proclamation to the French people.”

Calls went out to all nearby cities and villages for

volunteers to join the Maquis camps in Vercors. The Communist Party printed and

distributed leaflets in Grenoble calling for its supporters to take up arms.

“Don’t wait any longer to join the battle. There is no D-day or H-hour for

those who want to free the homeland. Let’s create everywhere combat groups to

support the movement and to defend ourselves against the Boches and the

murderous miliciens.” The calls were met with great enthusiasm. Within days,

the number of Maquisards in the mountains increased tenfold to several

thousand. This sudden influx of newcomers in the ranks of the Maquis created

immediate problems: they had to be armed, fed, clothed, supplied, and trained

before they could engage the enemy. Paradoxically, it worked to the benefit of

the Germans who preferred to have the Maquisards concentrated in the mountains,

away from the cities and main communication arteries, rather than wreaking

havoc in their rear areas.

The problems were not limited to Vercors but extended

throughout France. An intelligence report of the French Forces of the Interior

on June 13 warned:

The ranks have grown considerably and the recruitment

cannot be stopped. Those who have arms do not have sufficient ammunition. If a

considerable effort is not carried out, we will witness the massacre of the

French resistance.

All the partisan groups throughout France demand the same

thing: arms, ammunition, money, medications. All claim to have permanent

parachuting areas that they control where supplies can be sent day or night,

with or without prearranged signals.

FFI tried to stop the rush to insurrection especially when

reports of German atrocities and reprisals began arriving. The Germans

recovered quickly from their initial surprise on D-Day and moved swiftly to

restore order. Reinforcement divisions on their way to Normandy often went out

of the way to sweep the areas of Maquisards and leaving a swath of blood on

their wake. On June 9, in the city of Tulle, ninety-nine hostages were hanged

from trees and balconies. On June 10, the Germans massacred and burned alive 634

inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane, twenty miles northwest of Limoges.

On June 10, General Koenig issued the following clandestine

order to his subordinates in France: “Rein in to the maximum guerrilla

activity. Impossible at this time to provide you with arms and ammunition in

sufficient quantities. Break contact with the enemy everywhere to reorganize.

Avoid big gatherings. Operate in small isolated groups.” On June 17, Koenig

further instructed to avoid gatherings around armed groupings of elements who were

not armed and ready to fight. The focus of the guerrilla had to shift away from

mobilizing the population in general insurrection and toward classical

objectives such as disrupting enemy communications, railroad traffic, and

long-distance telephone lines.

The efforts to throttle back the enthusiasm of the Maquis

had little effect in Vercors. On July 3, 1944, the civilian authorities in the

massif announced the restoration of the French republic in Vercors. A

proclamation posted in all the towns and villages of the area informed the

citizens that “starting from this day, the decrees of Vichy are abolished and

all the laws of the republic have been restored…. People of Vercors, it is

among you that the great Republic is being born again. You can be proud of

yourself. We are certain that you will know how to defend it…. Long live the

French Republic. Long live France. Long live General de Gaulle.” The flux of

would-be fighters from the cities continued. Most of them had little experience

and there were many who had never fired a weapon.

An initial conflagration with the Germans, a harbinger of

things to come, did not bode well for the Maquis of Vercors. On June 10, two

companies of German soldiers attacked Saint-Nizier, a key mountain pass in the

northern extremity of the Vercors, which dominated the city of Grenoble in the

valley below, only a few miles to the northeast. Saint-Nizier was an excellent

observation point for all the automobile and railroad traffic into and out of

Grenoble. The Maquisards holding the pass had little military experience but

were able to hold out for several hours until more seasoned and better-equipped

men arrived from other camps. The Germans retreated but returned on June 15.

This time, there were between 1,000 and 1,500 German soldiers against 300

Maquisards stretched along a front of 2.5 miles. Within a few hours, the

Germans broke through their defenses, entered the town, and burned it down.

Throughout June, the Germans assembled forces and equipment

for the final assault on Vercors, which they gave the code name Operation

Bettina. Over 1,500 reinforcements arrived in Valence, a city west of Vercors,

among them troops specialized in mountain fighting and anti-guerrilla

operations. Seventy airplanes and armored equipment were positioned at the

airfield of Chabeuil, just south of Valence. General Pflaum took special care

in retraining and preparing the 157th Reserve Division for the upcoming battle.

He restructured the division around mobile columns who could operate more

effectively in Maquis territory. He supervised personally the instruction of

each unit of infantry and insisted on special drills at night and in

camouflage. He was able to change completely the division’s state of mind,

which resulted in a marked improvement in the ability of his soldiers to fight.

The German preparations did not go unnoticed by the French

Maquisards. Spotters observing the German movements from the mountains reported

in detail the preparations to the Vercors military commanders. They in turn

sent appeals for help of increasing intensity to their superiors in Algiers and

London.

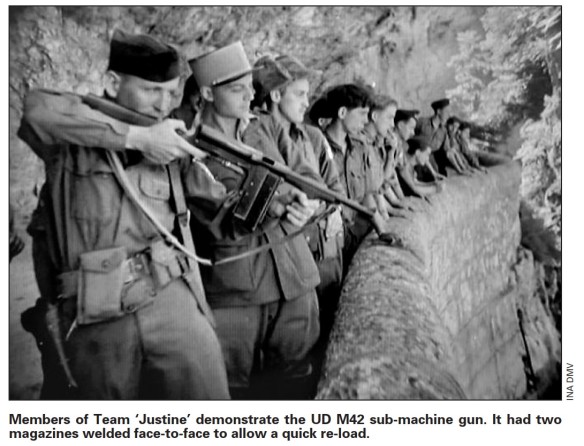

To strengthen the Maquis of Vercors and to coordinate

guerrilla attacks against the German lines of communications, the OSS

dispatched a team, code-named Justine, of two officers and thirteen enlisted

men from the French OGs based in Algiers. Captain Vernon G. Hoppers and First

Lieutenant Chester L. Myers led the team. They left Algiers in the evening of

June 28 and reached the designated drop zone near Vassieux at 0100 hours on

June 29. The sky was clear, the weather was calm, and the entire team

parachuted in perfect form to the reception area organized by the Maquis on the

ground. They moved all the containers dropped with them to a farmhouse nearby and

began distributing the supplies to the Maquisards.

They had been there for a few minutes when the excited

Frenchmen brought in another five parachutists. They belonged to an

inter-allied team, code name Eucalyptus, commanded by British Major Desmond

Lange. It included another British officer, Captain John Houseman, two

Frenchmen of the FFI, and a French-American member of the OSS Special

Operations branch, First Lieutenant André E. Pecquet, the radio operator of the

team. The French reception committee and the villagers were impressed and

excited by the presence of twenty Allied soldiers in their midst. They served

coffee, dark bread, and rich butter, which everyone took with gusto. The

paratroopers passed around their cigarettes and a lively conversation ensued.

After a while, vehicles arrived to transport the paratroopers—a smart private

car for the Eucalyptus team and a special bus for the American OGs. They were

taken to Vassieux and accommodated in villagers’ houses where they were able to

rest for a few hours.

The next day, Commandant François Huet, the Maquis leader in

the area, arrived early. He had coffee with the paratroopers and asked them to

attend the hoisting of the flag, a short ceremony that nevertheless astonished

the new arrivals for the strict military procedure with which it was conducted.

Houseman described in his diary what happened next:

On the way back the people of the village had turned out

to welcome us. We were shaken by the hand a score of times. The children kissed

us, and the infants were held up also to be kissed. Bouquets were pressed into

our arms—the whole unrehearsed greeting was very touching. They behaved as

though our very arrival had liberated them from the burdens and fears of

occupation.

The two teams began conducting their assigned missions

immediately. Eucalyptus acted as liaison between the Vercors commanders and the

Special Forces Headquarters in London. The OGs began training the Maquisards on

the use of British and American equipment at hand and in planning strikes

against the Germans. The news of the arrival of the Allied paratroopers spread

fast, and the FFI commanders wanted them to visit the area to boost the morale

and confidence of the Maquisards. On June 30, Captain Hoppers and a corporal

from Team Justine, Houseman from Eucalyptus, and a Maquisard escort went on a

three-day “see and be seen” tour in the southern part of Vercors in the

department of Drôme.

In contrast with the sharp-looking military personnel in

Vassieux, the Maquisards in these areas were “young and middle aged men, tough

and rough-looking from months of hard living, some dressed in what remained of

their wartime uniform, others in any civilian clothes they had managed to

scrounge.” They had only a fair supply of arms, ammunition, and explosives.

Throughout the villages they visited, they—the first Allied officers to visit

the area—were treated as the saviors of France. People simply did not know how

to express their delight and gratitude. Houseman wrote about the reception they

received in the town of Aouste, the last town they visited at the southern end

of the Vercors massif:

As we entered by some smallish streets I happened to see

a young girl staring at us—she stared for a moment only. Turning round on her

bicycle she shot off into the town itself—the news was out. No town crier can

have had such a response.

We stopped at a small shop and shook hands (I think we

were kissed as well) with the people inside. Wine appeared, and I had scarcely

raised my glass, when I heard a seething mob outside in the street—the people

of Aouste had come immediately to welcome us. They surged round us, shaking our

hands and hugging us—all were talking at once, and my very poor French met its

Waterloo. Armed with flowers and carrying children, they kept on streaming in,

telling us of their experiences, asking us when the invasion armies would come

and thanking us time and again for coming to their country and to their town.

The bouquets of red, white and blue flowers by now covered the large table in

the shop—more wine was brought up and the children reappeared with red, white

and blue ribbons in their hair.

After an hour or so we left the shop to make what proved

to be nothing less than a regal procession through the town. We had to walk at

the head of this excited ever-growing crowd along the main street to an outpost

at the far side of the town. Men saluted us, the women clapped, children ran to

kiss us and give us more flowers to carry. People rushed into the road and held

up the cavalcade to grasp us by the hand and to embrace us. On our way back, an

elderly woman ran across the road with tears in her eyes, to tell me about a

relation she had lost and to ask the ever-expectant question “when will the

invasion from the south begin?”

Upon return of the inspection group to Vassieux, both teams,

Justine and Eucalyptus, reported through their channels the need to send arms

and supplies to Vercors. They also advised the FFI military staff on measures

they could take to strengthen the ranks and discipline of the Maquisards. In

early July, Commandant Huet decided to militarize the volunteer force and return

to the military tradition of regular troop units. “In the past two years,” Huet

wrote to his subordinates, “the flags, the standards, the pennants of our

regiments and our battalions have been asleep. Now, with a magnificent drive,

France has risen against the invader. The old French army that has shone in the

course of centuries will reclaim its place in the nation.”

The old camps and companies of civilians were reorganized

into alpine battalions and even an armored battalion, which included a section

of irregular African riflemen from Senegal. Efforts were made to standardize

the uniforms, using in part battle dress uniforms that had arrived with teams

Justine and Eucalyptus. Requests were made to send more uniforms as well. In a

report to London, Lieutenant Pecquet, the French-American radio operator of

Eucalyptus, said that proper uniforms were a question of self-respect for the

French, who were very sensible to the enemy propaganda that described the

Maquisards as terrorists.