Hornsby developed a caterpillar artillery tractor before the war based on agricultural machines. It meant heavier machinery could be carried than traditional horse-drawn artillery

Little Willie at the Tank Museum, Bovington

An early model British Mark I “male” tank, named C-15, near Thiepval, 25 September 1916. The tank is probably in reserve for the Battle of Thiepval Ridge which began on 26 September. The tank is fitted with the wire “grenade shield” and steering tail, both features discarded in the next models.

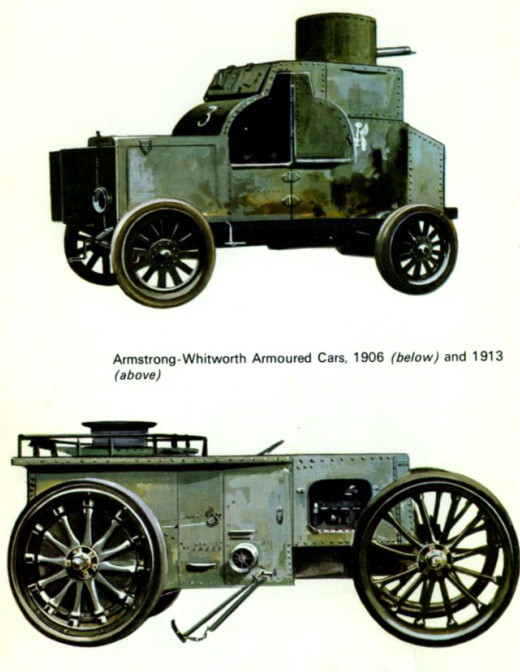

The Wolseley Car Company had shown a petrol-driven car with

a 16 horse-power Daimler engine at the Crystal Palace show of 1902. It had been

designed by Mr Frederick Sims, mounted a Maxim and was in some sort covered

with armour plating. In fact it was ahead of its time. The engine was too

feeble and the great weakness, as every pioneer motorist knew, lay in the

wheels. Pneumatic tyres had been in use for a long time but were still not to

be relied upon even on tarred roads. Heavy vehicles still, and for a long time

to come, stuck to the solid variety and put up with the jolting and low speed.

Nobody was much interested in Mr Sims’ car and it was quietly taken to pieces

again. In 1908 the Liberal Government gave to the cavalry the only new weapon

to be added before 1914. It was a sword; a very fine sword; a shovel would have

been far better value.

The reign of Edward the Peacemaker saw much happening in new

forms of military hardware. In 1904 a Danish officer, Major-General Madsen,

invented a light automatic gun which weighed only five pounds more than a

rifle, had a mechanism of the simplest kind and was better by far than anything

of the kind for a long time to come. Years later, on 6 June, 1918, an official

statement was made in the House of Lords that ‘the present Madsen gun is by

many considered “the most wonderful machine-gun of its kind ever invented” and

that it was admittedly superior in many respects to either the Lewis or the

Hotchkiss guns’. The gun was taken into service by the Danish cavalry but the

War Office in Pall Mall was not interested. Some years later, when the War

Office had moved to its fine new home in Whitehall and handed over Pall Mall to

the Royal Automobile Club, it brushed off Colonel Lewis in much the same way.

The Madsen gun would have been cheap. By the time of First Ypres the Government

would have paid any asking price for such a weapon. By then it was too late.

Efforts were made to get hold of some but Germany prevented the sale and

collared the guns herself. In a way this disinterest in automatics was a

compliment to the soldier. With the SMLE a recruit before leaving his Depot

could get off fifteen aimed rounds a minute; real experts could manage thirty.

The long-service regular infantryman was the best marksman in any army, as the

Germans readily admitted when the clash came. Nobody seemed to understand that

hastily raised units could not be expected to come anywhere near this standard.

The attitude of civilian ministers in the new Liberal

Government of 1906 was soon made plain to Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien when he held

the command at Alder-shot; ‘One day he (a Minister whose name had been struck

out by Lady Smith-Dorrien) honoured me at lunch, and I used the occasion to

impress on him, as a member of the Government, that it was most important that

we should be armed with the new Vickers-Maxim machine-gun, which was half the

weight of the gun we then had, and much more efficient, and I urged that

£100,000 would re-equip the six divisions of the Expeditionary Force. Mr —

jeered at me, saying I was afraid of the Germans, that he habitually attended

the German Army at training and was quite certain that if they ever went to war

“the most monumental examples of crass cowardice the world had ever heard of

would be witnessed”.’ Such, apparently, was Cabinet thinking in 1909. It is

hardly wonderful that any soldier of an innovative mind did not waste his time

by pressing ideas.

During Smith-Dorrien’s tour at Aldershot, in 1910, there was

a demonstration by the earliest of the British petrol-engined tractors, a

Hornsby chain-track. This was a splendid vehicle that looked as if it owed

something to Mr Heath Robinson or Mr Emmett. The exhaust led into an impressive

smoke-stack; the chains that drove it were surmounted by wooden blocks about

the size and shape of those commonly used for paving roads and the whole was

mounted on powerful springs that bounced it about alarmingly. Among those

watching was General ‘Wullie’ Robertson, later to be CIGS under Lord Kitchener.

He held the machine ‘to have a great future as a tractor for dragging heavy

guns and vehicles across broken ground. Universal sympathy was extended to the

drivers, who, in consequence of the caterpillar’s violent up-and-down motions,

experienced all the sensations of sea-sickness, and looked it’. In spite of

that there was no denying that the thing worked.

The Committee of Imperial Defence, however, was occupied

with more important matters. Between 1907 and 1914 the Channel Tunnel came up

for discussion fourteen times. Lord Wolseley’s Memorandum of 1882 was

resurrected and papers submitted by Field-Marshal Lord Nicholson, Mr Churchill,

Colonel Seeley and Sir John French. There is no mention of caterpillar tractors

anywhere in the Committee’s agenda over these years. As soon as the war started

and the demand came for guns heavier than the usual field pieces the question

of how they were to be moved along the roads of France demanded answer. Very

quickly, for Kitchener was now in charge, the War Office placed orders in

America for fifteen of the Holt machines. With 75 hp petrol engines, the best track

then on the market, and a weight of 15 tons (the Hornsby weighed 8) they could

manage a speed of 15 mph, though this fell to 2 with a gun hooked in. It was

still better than a large team of Clydesdale horses and they were soon at work

in France. Only a few people saw in them the beginnings of a war-winning

fighting machine.

It would be wrong, however, to assume that indifference was

limited to the allied camp. The German possessed one great advantage which

they, too, neglected. When the Zeppelin first appeared it became plain that

engines far more powerful than those used on roads were needful. After much

experiment, the firm of Maybach produced one of 450 hp. No other country had

anything like this. Fortunately no effort was made to apply the knowledge to

land-bound vehicles. The Maybach was far too heavy and clumsy for such uses.

Apart from the Rolls-Royce, which was in a class of its own, the best

motor-cars were made in France with Germany a good second. England lagged badly

behind; the United States produced excellent machines, the Hudson being perhaps

the fastest, but these belonged to quite another world.

To blame the Army for living happily in the past would be

entirely unfair. Soldiers, like everybody else, could hardly fail to see how

swiftly the country was becoming mechanized. As early as 1906 the land speed

record had risen to more than 125 miles per hour. At the end of the following

year London contained 723 motor taxi-cabs, a figure that had risen within two

years to just under 4,000. It was also noticeable that by far the greater

number of these were of French manufacture, Unic, Darracq and, above all, the

two-cylinder Renault that clung on for a very long time. The year, 1909, saw

the first movement of a formed body of troops by road. It was, admittedly, a

publicity stunt by the Automobile Association but the fact remained that a

composite battalion of the Guards, complete with all impedimenta, was carried

from London to Brighton and back in several hundred private cars at a good

round speed and without a hitch. The only military lesson learned was that the

service cap universally called a Brodrick, though St John Brodrick, Earl of

Midleton, denied all responsibility for it, blew off for want of a chin-strap.

This omission was made good. It was the AA, months before Lord Kitchener’s

call, that coined the phrase ‘The First Hundred Thousand’. In July, 1914, its

membership had reached 89,198 of whom 3,279 had been elected during the

previous month or so. It was confidently expected that the magic figure would

be reached by the time of the Olympia motor show and a great celebration dinner

was planned. Fate, however, got in first. There was no motor show in August,

1914.

It was not the General Staff, however, but the Home

Secretary who first realized that the motor car might have an unexpected

military use. On a day in the wonderful summer of 1911 Mr Churchill attended a

party at No 10 Downing Street where he fell into conversation with Sir Edward

Henry, Chief Commissioner of Police. As they talked about the European

situation and its gravity, Sir Edward casually remarked that by an odd

arrangement the Home Office was responsible, through the Metropolitan Police,

for guarding the whole of the Navy’s cordite reserves in the magazines at

Chattenden and Lodge Hill. This being the first the Home Secretary had heard of

it he pressed Sir Edward hard. The guard, it seemed, had for years consisted of

a few London bobbies armed with truncheons. To the question of what would

happen if a score of armed Germans turned up in motor-cars Mr Churchill

received the interesting answer that they would be able to do as they liked. He

left the garden party and telephoned the Admiralty. As both First Lord and

First Sea Lord were absent he spoke to an Admiral ‘who shall be nameless’. He

made it quite plain that he was not taking orders from any panicky civilian

Minister and flatly refused to send Marines. A second call to Mr Haldane at the

War Office had two companies of infantry installed within a few hours. The

motor car had introduced something new into military matters.

It was left to that erratic genius Mr H. G. Wells to move

things on a little further. Though the son of a professional cricketer, he had

some ideas that were certainly not cricket. In 1903, being well into what is

now called ‘science fiction’, a market that he had almost to himself, he sent

to the Strand Magazine a story of some future war in which armed and armoured

machines crawled over the countryside on their tracks and fought battles with

each other. It was called The Land Ironclads. Later he warmed to his work and

told not merely of wars in the air between various branches of the human race

but also of battles with invaders from outer space. All were regarded with

equal seriousness. The Holt tractor from America, an efficient petrol-driven

machine running on tracks, was given a demonstration at Aldershot. Its faults,

which were many, were pointed out; its virtues and potential were ignored. The

military mind, mercifully, knew no national boundaries. Not only did no other

War Office want Mr Holt’s tractor; none even wanted buses or lorries.

The scientific Germans, however, did not entirely abandon

the idea. In 1913 a Herr Goebel produced a machine of his own design. It was,

according to German custom, huge and ponderous; no picture seems to have

survived but it was described as resembling what we know as a tank, to have

been covered in thick armour and to have bristled with guns. In 1913 he drove

it over a high obstacle at Pinne, in Posen; the following year he produced it

before a huge crowd at the Berlin stadium. It broke down half way up the first

bank and refused to be started again. The crowd became truculent and demanded

its money back. Herr Goebel and his machine disappeared from history.

The Belgians took a few of their excellent Minerva cars to

the Cockerill works in Antwerp and had them fitted with a mild steel armour.

That apart, the armies of the great industrial powers of Europe walked slowly

towards each other in the summer of 1914 with masses of man-power and

animal-power as great armies had done since man discovered war. A reincarnated

Wellington could have taken command of any of them after only the shortest

refresher course.

In the rear areas of the BEF some concession was made

towards modernity. The War Office as long ago as 1900 had set up a Mechanical

Transport Committee, a brave gesture towards the coming century. It found

little occupation in Pall Mall but survived the translation to Whitehall in

1907. In 1911, Coronation year, new life was breathed into it with the

introduction of two subsidy schemes; these provided a means of mechanizing some

parts of the Army on the cheap. Civilian companies were given money on the

understanding that they would build vehicles more or less to a specification

and would on mobilization hand them over. The scheme did not work out too

badly. Each Division had a supply column of motor-lorries, working,

theoretically, between railhead and the Divisional Train. Homely names on their

sides like Waring & Gillow or J. Lyons rather spoilt the picture of a

twentieth-century army but the Army Service Corps drivers plied their new trade

well enough. All army ambulances remained horse-drawn; the best of the

motor-driven ones were furnished, along with their crews, by those old

reliables the British Red Cross Society and the Salvation Army.

On 31 May, 1915, Lord Kitchener submitted a secret report to

the Cabinet which set out the entire state of affairs very clearly. On

mobilization the Army had owned exactly 80 motor-lorries, 20 cars, 15

motor-cycles and 36 traction-engines. The subsidy scheme brought the lorry

total to 807; another 334 had been instantly commandeered. The 20 cars

simultaneously jumped by 193 and the motor-cycles by 116. On the day Kitchener

signed the report there were on the strength a further 7,037 lorries, 1,694

cars, 2,745 motor-cycles and 1,151 motor-ambulances. The Army Service Corps had

grown from 450 officers and 6,300 other ranks to ‘a strength today of 4,500

officers and 125,000 other ranks, i.e. 5,000 more than the whole of the Regular

Forces in the United Kingdom previous to the outbreak of war’. Petrol,

including that for the Royal Flying Corps, was being consumed at the rate of

35,000 gallons a day.

The war was still very young. On Armistice Day 1918 the Army

had on charge in all theatres 121,692 motor vehicles along with 735,000 horses

and mules.