Forty-one-year-old Mark Antony stood on the terrace of the

palace at Tarsus and watched with growing anticipation as the huge barge rowed

slowly up the Cydnus River from the nearby Mediterranean harbor at Rhegma. A

beautiful child, Antony had grown into a handsome and impressive man, with

broad shoulders and a large chest. His neck was as thick as a wrestler’s. His

jaw was square and set, his mouth large, his nose well defined, his eyes

hooded. Yet, for a man with his reputation as a fearsome fighter in battle, he

could be quite vain, and fashionably wore his hair curled into ringlets by

curling tongs.

Around Antony there were smiles on the faces of his generals

and the freedmen on his staff, as all eyes followed the slow course of the

glittering Egyptian barge coming up the river. After much prevarication,

Cleopatra, the twenty-eight-year-old queen of Egypt, had finally succumbed to

Mark Antony’s summonses and had sailed from Egypt to meet with him here in

Cilicia.

The capital of the Roman province of Cilicia, Tarsus was a

center of government, commerce, and learning—its university was famed for its

Greek philosophers. Tarsus had grown prosperous since its foundation 650 years

before, courtesy of the flax plantations of Cilicia’s fertile interior. These

provided the raw material for the linen and canvas factories and ropemakers of

Tarsus, whose products were exported the length and breadth of the Roman

Empire. The town was also strategically placed, being not far from the Cilician

Gates, the only major pass in the Taurus Mountains just to the east. Rome’s

longtime enemy the Parthian Empire, whose homeland occupied modern Iran and

Iraq, lay beyond those mountains. Julius Caesar had based himself in Tarsus in

47 B.C. following his conquest of Egypt. And during this stay, Caesar had

apparently granted Roman citizenship to the free residents of Tarsus. Antony,

since his arrival, had added to the honors, making Tarsus a free city by

removing all taxes on its citizens, and also freed all those who had been sold

into slavery in the city.

Word had reached Antony that Cleopatra was on her way when

her fleet was sighted sailing up the Syrian coast. For a long time it had

seemed that she would not come. She had ignored several letters, from Antony

and from friends, urging her to meet Antony in Cilicia. So, the previous fall,

Antony had sent Quintus Dellius, a member of his entourage, to the Egyptian

capital to personally require Cleopatra to meet him in Cilicia and answer the

accusation that she had provided financial support to Cassius the Liberator.

Dellius was a good choice as envoy. A renowned historian, he was as wise as he

was diplomatic. In Alexandria he had found Cleopatra very wary of Antony. She

had met Antony once, at Alexandria, when she was fourteen and he was a young

cavalry colonel in the army of Roman general Aulus Gabinius. General Gabinius

had brought his army down from Syria to reinstate Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy

XII, on the Egyptian throne after he had been deposed by his own people. Even

in those times Antony had a fearsome reputation as a soldier. Only recently he

had taken a rebel Jewish stronghold in Judea, while in the weeks prior to

arriving in Alexandria he had led General Gabinius’s cavalry advance guard in

swiftly seizing the Egyptian fortress of Pelusium.

During the fourteen years since that brief encounter between

princess and colonel, Antony’s military reputation had multiplied. By the time

that Dellius arrived at Cleopatra’s court, the queen had heard how Antony dealt

with opponents: he’d had hundreds, including famous orator Cicero, beheaded

following Caesar’s murder. And after the Battles of Philippi, he had executed

the officer responsible for the death of his brother Gaius, on Gaius’s tomb.

Realizing this, Dellius had assured Cleopatra that she had nothing to fear from

his master. Antony, said Dellius, so Plutarch records, was “the gentlest and

kindest of soldiers.” Dellius even advised Cleopatra to go to the Roman general

in her best attire, to impress him. Cleopatra, says Plutarch, had some faith in

Dellius’s assurances, but had more faith in her own attractions. As Plutarch

points out, those attractions had won her the hearts and support of Julius

Caesar, and before him, of the Roman military commander in Egypt, Pompey the

Great’s eldest son, Gnaeus Pompey. And now Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, consort

of the later dictator Caesar and mother of his son Caesarion, was coming to

Antony, the latest Roman strongman, intent on dazzling him.

The Egyptians, the best shipbuilders of the age, were famous

for creating massive pleasure barges for their sovereigns, and the craft that

brought Cleopatra up the Cydnus was no exception. Its stern was gilded with

gold, and the billowing sails were made from purple, the rarest and most

valuable of cloths. The oars jutting from the outriggers on either side of the

barge were of shining silver; they dipped and rose in perfect harmony to the

tune of flutes, fifes, and harps. Cleopatra herself lay on a bed on the deck,

beneath a canopy of gold cloth, dressed as the goddess Venus. Around her were

pretty young boys costumed as Cupids. The queen’s female attendants, dressed as

sea nymphs and graces, steered the barge’s rudder and hauled on ropes to bring

in the sails. The awestruck people of Tarsus had never seen anything like it.

Crowding along both riverbanks, thousands of locals kept pace with the huge,

slow-moving barge as it came upstream.

Antony decided that he would receive Cleopatra seated on the

raised tribunal, or judge’s platform, in the Forum of Tarsus. When he arrived

with his entourage to take his place on the tribunal, his Praetorian Guard

bodyguard spread around the city marketplace to secure it. They found the place

deserted—everyone had gone to see Queen Cleopatra. Shakespeare was to write

that the very air left the marketplace, such was her attraction. Once the barge

docked, Antony sent a message to Cleopatra, inviting her to dine with him.

Cleopatra sent back a message of her own, inviting Antony to instead dine with

her aboard her pleasure barge. Intrigued, Antony accepted the queen’s

invitation. According to Plutarch, it was said by the Tarsians that this would

be like a meeting of the gods—that it was as if Venus had come to feast with

Bacchus.

Antony arrived at the barge to find that sumptuous

preparations had been made. Most magnificent of all were the illuminations. As

he stepped aboard, tree branches were let down bearing glowing lamps forming

patterns, some in squares, some in circles. “The whole thing was a spectacle

rarely equaled for beauty,” Plutarch was to comment.

Now Antony was greeted by the diminutive, elegantly attired

Egyptian queen. Her olive skin was as smooth as silk. Her jet black hair had

been elaborately braided by personal hairdressers who worked on her coiffure

for hours every day. An asp of solid gold, her royal symbol, projected from the

front of a golden diadem on her head. Her elaborately decorated dress was almost

skin-tight, and accentuated her figure. A picture to behold, she was unlike any

woman Antony had previously seen. By all accounts Cleopatra was not an

incomparable beauty. She was petite and plain. But she had a charisma that

struck all who met her. The attraction of her person and the charm of her

conversation were bewitching, says Plutarch. According to Roman historian

Appian, Antony fell in love with her at first sight. That first night Antony

was polite, and enjoyed Cleopatra’s hospitality, although at this first meeting

both were restrained, as the young queen explained all that she had contributed

to the fight against Cassius the Liberator. Antony never raised the subject of

Cassius again.

On the day following the dinner on the barge, Cleopatra went

to dine with Antony in Tarsus. He strove to emulate or even outdo her but could

not match the magnificence of her reception. And he found himself trailing in

the wake of her conversation. She could speak numerous languages fluently and

was highly intelligent. According to later Arab writers, to add to her many

attributes Cleopatra was a learned scholar. Antony, in comparison, was a man

without gloss, or pretense. He was a soldier, and what you saw was what you

got. As Cleopatra shared his table, he was the first to poke fun at his own

lack of refined wit or sophistication. He was more comfortable with

hard-drinking men friends, telling bawdy barracks jokes. It was then that

Cleopatra demonstrated how clever she truly was. She began to tell Antony dirty

jokes—“without any reluctance or reserve,” says Plutarch. And by lowering

herself to Antony’s level, she captivated him. Here was a woman who could

drink, tell crude jokes, and gamble like a man, yet was still a sexual

temptress. He fell head over heels in love with her. Appian was to say, “He

became her captive as if he were a young man.”

After that, says Cassius Dio, Antony gave no thought to

honor but became Cleopatra’s slave, and devoted his time to his passion for

her. Abandoning his plans to invade Parthia, Antony accepted Cleopatra’s

invitation to return to Egypt with her. They promptly sailed to Alexandria.

There, Antony, Cleopatra, and the members of their entourages entertained each

other day in, day out, sparing no expenditure, calling themselves the

Inimitable Livers. Plutarch tells the story that during this period a friend of

his own grandfather visited the kitchens of the royal palace at Alexandria and

found eight wild boars in various stages of roasting on the spit. The visitor

remarked that the queen must be entertaining a large crowd, but the cook

replied that apart from Cleopatra and Antony there were only ten other dinner

guests. Not knowing when Antony would call for food to be served, the cook was

preparing the same meal, time and again, so that when the call came, the meat

would go to the guests perfectly cooked.

According to Appian, himself a native of Alexandria, Antony

dispensed with his military uniform and his general’s insignia, and wore a

square-cut Greek tunic and white Attic boots. His family claimed descent from

the mythological Greek figure Hercules, and now that he was wooing Cleopatra,

who was herself of Greek heritage, he took every opportunity to advertise his

Greek connections. And, totally trusting of Cleopatra, he let his bodyguards

idle in their quarters and went about without an escort.

Cleopatra was with Antony day and night. She drank and ate

with him, she played dice with him, she hunted and fished with him, and when he

undertook his daily weapons training she was there, watching and admiring. She

quickly talked him out of his plan to invade Parthia. Cleopatra was looking for

a new Caesar, a man alongside whom she could rule the world. What Antony needed

to concentrate on, she told him, was overthrowing the other triumvirs and

gaining control of the Roman Empire for himself. Marcus Lepidus, Antony knew,

could easily be elbowed aside; he had only been brought into the triumvirate

for the sake of appearances. But the powerful young Octavian was a much more

difficult opponent. In 44 B.C. Antony had made the mistake of underestimating

the then eighteen-year-old Octavian when the youth had turned up at Rome to

claim his inheritance from the assassinated Caesar. Octavian was wiser and more

cunning than men three times his age, and Antony’s initial grab for power at

Rome had failed because of the young man’s maneuvering. Antony had been forced

to settle for the three-way sharing of power with Octavian and Lepidus. But

now, at Cleopatra’s urging, Antony began to see a singular role for himself.

Ignoring reports that Parthian forces were massing in

Mesopotamia to the east of Syria—assuming this was merely in response to rumors

of Antony’s planned invasion of Parthia—Antony focused on Italy and Octavian.

The officers on Antony’s staff advised against opposing Octavian, and warned

him of the danger posed by the Parthian buildup in Mesopotamia. But he ignored

them; Antony had ears only for Cleopatra. Antony’s quaestor—his quartermaster

and chief financial officer—Lucius Philippus Barbatius, was so disgusted with

his commander that he quit his post and sailed for Italy, where he would work

against Antony’s interests. Meanwhile, Antony’s legions, including the 3rd

Gallica, maintained their positions in Bithynia. From there they could march on

Italy if the need arose, to support Antony’s latest bid for power.

General Quintus Labienus sat in the old Seleucid palace at

Antioch, capital of Syria, posing for a Greek portraitist who was sketching his

profile. Not so long ago Labienus had been a stateless youth, a man with a

price on his head, on the run from Mark Antony. Now he was the conqueror of

Syria, and his troops had hailed him imperator. This ancient title, which

literally meant “chief ” or “master,” had much symbolic meaning. In time

mutating into the word “emperor,” it was a title bestowed on victorious Roman

generals by their troops. Both Pompey and Caesar had been awarded the honor.

So, too, had Mark Antony, who began his letters with the title. And now

Labienus, only in his twenties, had the title and the victory to match Antony.

Now that he occupied Antioch, young Labienus ordered his treasurer to mint gold

coins for his troops when the time came to pay them in October. On those coins

would be stamped young Labienus’s image, from the sketch now being drawn, and

his name, added to which would be two titles: “IMP,” for imperator, and

“Parthicus.” At any other time, the Parthicus title would signify a Roman

general who had defeated the Parthians. But Labienus had just succeeded in

taking Syria from Mark Antony—at the head of a Parthian army.

The previous fall, just before the Battles of Philippi,

young Quintus Labienus, then a mere Roman tribune on the staff of Liberators

Brutus and Cassius, had crossed the Euphrates River in search of Orodes II,

king of the Parthians. The Parthians were a nation that had grown out of the

Parni, a tribe of nomadic horsemen who had built a rich empire astride most of

the trade routes from the Far East to the Roman world. Labienus had been sent by

the Liberators to plead for more military aid against Antony, Octavian, and

Lepidus. Orodes, a member of the ruling Arsacid royal house, had previously

permitted a contingent of Parthian horse archers to join the Liberators, and

they were among four thousand mounted archers from Media, Arabia, and Parthia

riding for brothers-in-law Brutus and Cassius by the summer of 41 B.C. But the

Liberators, knowing how devastatingly effective the Parthian horse archers

could be, after Cassius had faced them during the famous defeat at Carrhae,

wanted many more of them.

Although he was young—only about twenty-two at that

time—Colonel Labienus was an excellent choice for the mission to Parthia. With

a long nose; thick, curly hair; and a beetled brow, Labienus was not handsome,

but he was bright and energetic. More importantly, he had a famous father—Major

General Titus Labienus, Caesar’s brilliant and brave second in command, and

later Pompey’s general of cavalry after Labienus changed sides early in the

civil war. Both Pompey and Labienus Sr. had been feared and respected by the

Parthians. When young Quintus Labienus was escorted into the presence of the

Parthian king, old Orodes had given the young Roman a hearing—he knew that

Brutus and Cassius might end up controlling the Roman Empire. Orodes kept

Labienus waiting frustrating weeks at his court without answering him. And

then, in November, crushing news had reached Parthia, telling of the defeat of

Cassius and Brutus in the Philippi battles.

Aware that Labienus would be a wanted man in Roman

territory, Orodes had subsequently given the young Roman sanctuary at his

court. In early 40 B.C., once he learned that Antony had fallen for Cleopatra

and had withdrawn to Egypt, and with news coming of conflict between Antony’s

family and Octavian in Italy, Labienus had begun to work on the Parthian

monarch, suggesting a very bold plan. Throughout their history, the Parthians

had never shown an interest in conquering the Romans, or even of taking large

slices of Roman territory for themselves. But they were constantly made nervous

by the aggressive Romans, and never failed to fight them if they threatened

Parthian territory. As recently as 53 B.C. they had destroyed a Roman army

under the consul Marcus Crassus when he invaded Parthia, and two years later

they had made a brief incursion into Syria. They were always looking to control

states that bordered Parthian territory, to create a buffer zone between

themselves and the Romans. Now, Labienus suggested, with Antony distracted and

with only small Roman garrisons in Syria, here was an opportunity to seize

Syria and other Roman provinces in the East, creating a massive buffer against

Roman expansion.

Appreciating the opportunity, Orodes had assembled an army

in Mesopotamia under the command of his eldest son, Pacorus. This Parthian

prince was apparently in his thirties. Pacorus had been involved in a major

military expedition in his twenties and was an excellent soldier. He was also

extremely well liked by all classes for his pleasant manner and sense of

fairness, and was the apple of his father’s eye. Realizing that to win popular

support in the Roman provinces the invaders must be seen to have a Roman

leader, Orodes appointed young Quintus Labienus, sponsor of the idea, joint

commander with Pacorus. This Parthian invasion force led by Pacorus and

Labienus consisted entirely of mounted troops. It numbered about ten thousand

men, the same size as the army that had defeated Crassus’s legions thirteen

years before.

In the spring of 40 B.C., this Parthian army had crossed the

Euphrates River at Zeugma, east of the Syrian city of Apamea, unopposed. The

town of Zeugma straddled the Euphrates at a narrow canyon, with its

administrative center on the Syrian side and suburbs on the Parthian side. With

the aid of local boatmen, the Parthian army was quickly ferried across. Taking

the province entirely by surprise, the Parthians quickly surrounded Apamea, a

260-year-old garrison city and eastern crossroads, which sat on the right bank

of the Orontes River overlooking the Ghab Valley. The Roman commander at Apamea

was the quaestor Decidius Saxa, younger brother of Mark Antony’s governor of

Syria, Major General Lucius Decidius Saxa. The younger Saxa, in his early

thirties and serving as financial deputy to his brother, closed the city gates

and refused to surrender Apamea when Labienus demanded its submission.

The governor, General Saxa, who had been one of two generals

commanding Antony and Octavian’s advance force in Macedonia at the time of the

Philippi battles, marched from Antioch, which lay farther west on the Orontes.

He arrived with a force of infantry and cavalry, and met Labienus in a pitched

battle in open country. Saxa attempted to use his auxiliary cavalry against

Labienus’s Parthians. But his mounted troops were no match for the Parthian

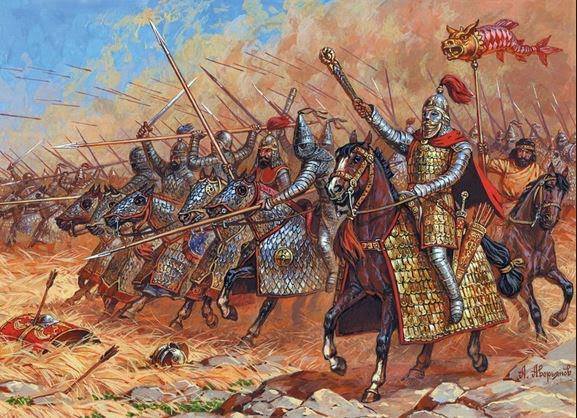

cavalry. Labienus’s horse archers drilled their opponents with arrows; then the

heavy cavalry moved in for the kill and mowed them down. Saxa and his infantry

retreated behind the walls and trenches of their marching camp. In the night,

Labienus had Parthian bowmen send thousands of leaflets flying into the camp

attached to arrows. Those leaflets urged the Romans to come over to Labienus’s

side, and when General Saxa saw the mood of his surrounded men change in favor

of Labienus, he broke out of the camp in the darkness. With a few supporters,

Saxa fled back to Antioch. Behind him, his men went over to young Labienus.

Labienus returned to Apamea, which Pacorus was still

besieging. The Roman garrison, now thinking General Saxa dead, went over to

Labienus. Saxa’s defiant younger brother was handed over to the Parthians and

executed. Labienus then advanced along the Orontes and surrounded Antioch. When

the city agreed to peace terms, General Saxa again fled, this time heading

northwest, toward Cilicia. The Antioch garrison then also joined Labienus.

Every city and town in Syria but one had soon gone over to the invaders. The

exception was Tyre. Here, Antony’s last supporters and loyal Tyrians combined

to stubbornly hold out. Because the Parthian besiegers had no naval support,

the Tyre garrison was able to get in fresh supplies by sea. Sending a ship to

Antony in Alexandria pleading for him to come to their aid, they prepared for a

long siege.

Now, with Labienus resident at the palace of the Seleucid monarchs at Antioch and enjoying his newly won power, a message from Jerusalem reached his co-commander, the Parthian prince Pacorus. It was from Antigonus, ambitious nephew of Hyrcanus, Jewish high priest. Antigonus promised a vast sum in gold and five hundred Jewish women to Pacorus if he used his forces to depose Hyrcanus.

Pacorus and Labienus now agreed on their tactics. The

Parthian army was divided in three. One part would accompany Labienus and the

foot soldiers he had won over in Syria as he advanced northwest into Cilicia.

His objective was to roll up all the Roman provinces east of Greece, hoping

that the garrisons in his path would come over to him as those in Syria had

done. Antony’s legions, including the 3rd Gallica, were the only unknown

quantity as far as Labienus was concerned. Sitting immobile in Bithynia while

their commander in chief caroused in Egypt, they represented the most powerful

card in the game. Labienus was hoping that he would be able to convince Antony’s

legions to abandon him the way he had abandoned them for Cleopatra.

The second force, made up entirely of cavalry under Prince Pacorus, was to advance down Judea’s Maritime Plain. At Joppa it would swing up into the hills and advance on Jerusalem from the northwest. The third force, also made up of Parthian cavalry and led by the Parthian general Barzaphanes, would sweep down through central Judea, follow the Jordan River as far as Jericho, then advance on Jerusalem through the hills from the northeast. The two Parthian forces would then link up outside Jerusalem and occupy the city, bringing Judea into the Parthian fold and installing Antigonus as their puppet ruler there. With the invasion just weeks old and Syria now under Parthian control, the three forces moved off on their individual missions. With news of civil war and chaos in Italy, and with Mark Antony still partying with Cleopatra in Egypt, the co-commanders were confident of success.

Meanwhile, the men of the 3rd Gallica Legion, sitting idly

at their camp in Bithynia, as they had been for months, with orders to stay

where they were, wanted to know what was going on. They had heard that the

Parthians had invaded Syria and Judea and had won swift victories. It hadn’t

been meant to be like that—it was supposed to be the other way around, with the

3rd Gallica and its brother legions marching into Parthia with Mark Antony. Now

Quintus Labienus was marching into Cilicia and drawing closer by the day. Why

weren’t Antony’s legions being ordered to prepare to confront the invading

upstart Labienus? And where in the name of Jove was Antony himself?

Two messages reached Mark Antony as he relaxed in Alexandria

in the early spring of 40 B.C. Both made him sit up with a start. He already

knew that the previous fall his brother Lucius had set off a revolt in Italy,

urged on by Antony’s ambitious wife, Fulvia. After initially occupying Rome,

being hailed by the populace, and being joined by thousands of retired soldiers

from Antony’s former legions and many raw levies, Lucius had been bottled up in

Perusia, modern Perugia in central Italy, north of Rome, by Octavian’s forces.

While Octavian himself would say in his memoirs that he felt Lucius was doing

Antony’s bidding, ancient authorities were convinced that Antony had no prior

knowledge of Lucius’s uprising. But if Lucius were to overthrow Octavian,

Antony would not have objected. Antony had learned that generals staunchly

loyal to the memory of Julius Caesar, and to Antony, including Publius

Ventidius and Gaius Asinius Pollio, had led thirteen legions to Italy from

Gaul, aiming to support Lucius.

But this latest news was not good. The relief forces had

been prevented from getting through to Lucius by Octavian’s eleven legions.

With the men of Lucius’s legions starving and unable to break through

Octavian’s complex entrenchments surrounding Puglia after months of fighting,

Lucius had surrendered, and the so-called Perusian War had come to an end.

Octavian had pardoned Lucius Antony, and had sent him to command on his behalf

in Spain. Fulvia had fled from Italy to Athens in Greece. And Lucius’s six

legions were being shipped to North Africa.

The second dispatch informed Antony that the Parthian

invasion of the Roman East was achieving spectacular success. The Parthian

prince Pacorus had entered Jerusalem and installed Antigonus as high priest.

Antigonus had sliced off the ears of his uncle, Hyrcanus, and sent him into

captivity in Parthia. Herod and his brother Phasaelus had been taken prisoner;

Phasaelus had committed suicide, but Herod and his family had escaped. Quintus

Labienus’s forces, meanwhile, had marched through Cilicia and as far as Ionia

and Lydia, with Greece tantalizingly close. Most cities and towns on his route

had surrendered without a fight. Only the island city of Stratonicea was

resisting, and was under siege by Labienus. General Saxa, Antony’s fugitive

governor of Syria, had been tracked down by Labienus, captured, and executed.

Now Antony finally stirred himself into action. Provided

with five warships by Cleopatra, he bade her good-bye and sailed for Syria,

ostensibly to help the port city of Tyre, which was still holding out against

Parthian siege. But as he was only accompanied by the one thousand men of his

Praetorian Guard bodyguard cohort, he bypassed Tyre and left the Tyrians to

their fate. Sailing on, Antony put in at Rhodes and then Cyprus, where he

learned that Labienus was plundering cities and temples in the territories he

had occupied to raise the gold to pay his troops. Still Antony’s eyes were on

Italy. Ignoring Labienus and the Parthians, he sailed on and landed in northern

Asia. There he sent for the two hundred warships he had ordered built the

previous year. Once the ships arrived, Antony took some of his legionaries from

Bithynia on board, but the bulk of his troops he ordered to cross the

Hellespont to Macedonia, away from Labienus and the Parthians, to await further

orders there. It is likely that his six legions were sent to a base Caesar had

created in Macedonia in 45-44 B.C. in preparation for his aborted Parthian

campaign. Antony himself sailed to Greece with his massive fleet, then

proceeded overland to Athens.

Antony’s wife, Fulvia, was waiting for him at Athens, and we

can only imagine the confrontation when they met. Ancient authorities say that

the ambitious Fulvia had encouraged Lucius to revolt because she was jealous of

Cleopatra’s influence over Antony, and had been determined to become the major

power broker, and sideline Cleopatra. Antony, meanwhile, blamed Fulvia for

Lucius’s failed revolt, which reflected badly on him. Exploding into a rage,

Antony is reputed by ancient authorities to have vented his anger on his wife.

In Athens, Antony was joined by Julia, his influential mother. After her son

Lucius’s surrender, Julia had initially fled to Sicily, which had been taken

over by Sextus Pompey, youngest and only surviving son of Pompey the Great.

Sextus had provided ships to take her to Greece, and senior members of Sextus’s

staff who accompanied her told Antony that their master was prepared to enter

into an alliance with him against Octavian. Antony responded that if he did go

to war against Octavian he would indeed ally himself with young Pompey.

As Antony spent the summer in Athens, a number of Antony’s

supporters flooded to him from Italy. They brought news that Generals Ventidius

and Pollio had assembled their legions at strategic coastal cities in Italy and

were urging Antony to come and launch his own bid to overthrow Octavian. At the

beginning of spring, Fulvia suddenly took ill. Leaving her in Greece, Antony

sailed from the island of Corfu with his two hundred warships, bound for Italy

and a showdown with Octavian. In the Adriatic he was met by Admiral Domitius

Ahenobarbus, who had previously fought for the Liberators and had been

something of a pirate since their deaths. Won over to Antony’s side by General

Ventidius, Ahenobarbus now allied his ships and troops to Antony. Landing at

the key naval city of Brundisium, modern Brindisi, Antony linked up with friendly

troops waiting nearby and lay siege to Brindisi, also sending forces along the

Italian coast to seize other cities. At the same time he sent word to Sextus

Pompey to act in accordance with their agreement. In response, Sextus’s forces

landed on Sardinia and wrested it from the two legions holding the island for

Octavian, and Sextus himself commenced operations against Italy’s southwestern

coast from bases he had established on Sicily.

As Antony continued the siege of Brindisi, he sent orders to

Macedonia for his legions, including the 3rd Gallica, to hurry across Greece to

the Adriatic coast, where his warships would ferry them over the Otranto Strait

to join him. As Octavian closed around Brindisi with forces that substantially

outnumbered Antony’s, and with Octavian’s best general, Marcus Agrippa, forcing

Antony’s troops to retreat elsewhere, Antony resorted to subterfuge. Each night

he sent ships away from Brindisi in the darkness carrying civilian passengers.

Next day those ships would return and land the civilians, armed and dressed as

soldiers, to let Octavian’s troops at Brindisi think that he was progressively

receiving his best troops from Macedonia.

News now arrived from Greece that Fulvia had died. According

to the Roman historian Appian, she had fallen sick because she could not endure

Antony’s anger with her and had subsequently wasted away with grief because he

had refused to see her on her sickbed. Shortly after Fulvia’s death, an

intermediary from Octavian went to Antony’s mother, Julia, at Athens, and urged

her to have her son come to the peace table with Octavian. The intermediary

went to Antony with the same proposal, and when his mother supported the

approach, Antony agreed. Now beyond Cleopatra’s influence, Antony concluded

that Octavian had far too much support in Italy for him to overthrow him, and

contented himself with sharing power and ruling the East.

Sending Admiral Ahenobarbus, who was despised by Octavian,

away to Bithynia to become its governor, and telling Sextus Pompey to withdraw

to Sicily and let him sort out matters with Octavian, Antony met Octavian at

Brindisi. Together they ironed out a new five-year triumval agreement. Octavian

would control the Roman empire in the West, Antony all the empire east of

today’s Albania. Marcus Lepidus was left with just two provinces in North

Africa. Octavian and Antony next met with Sextus Pompey at Misenum and sealed a

peace deal that gave him control of Sicily, Sardinia, and Achaea in Greece, and

promised him a consulship. In return, Sextus promised to marry his young

daughter to Octavian’s nephew once she was of marrying age.

Now, to cement their alliance, Octavian betrothed his elder

sister Octavia to Antony. Octavia, whose husband had recently died, was

apparently no beauty, but she was an intelligent and honorable woman, and it

seems Antony genuinely had affection for her. They quickly married, and Octavia

promptly fell pregnant. Now, as Antony and Octavian were feted in Rome for

their peace deal, Antony set the ball rolling to recover his eastern domains.

Now that Herod had arrived from Judea after escaping the Parthians, he had the

Senate decree Herod king of Judea and declare Antigonus, self-proclaimed Jewish

high priest at Jerusalem, an enemy of Rome. Herod was then provided with a ship

to take him back to the Middle East so he could raise a local force against

Antigonus. Anthony’s handy envoy Quintus Dellius went along as a Roman adviser.

Now, too, Antony ordered Publius Ventidius, his finest

general and loyal friend, to take the best Antonian legions, including the 3rd

Gallica, and throw Labienus and the Parthians out of Rome’s eastern provinces

and install Herod as king of Judea in accordance with the Senate’s decree.

Ventidius quickly sailed for Greece. The 3rd Gallica Legion, marching west

along the Egnatian Way across northern Greece with five fellow Antonian legions

to join Antony in Italy, was met on the march by Ventidius. He ordered them to

turn around and head for Asia, with him at their head. The men of the Gallica

would at last get their opportunity to fight the Parthians.