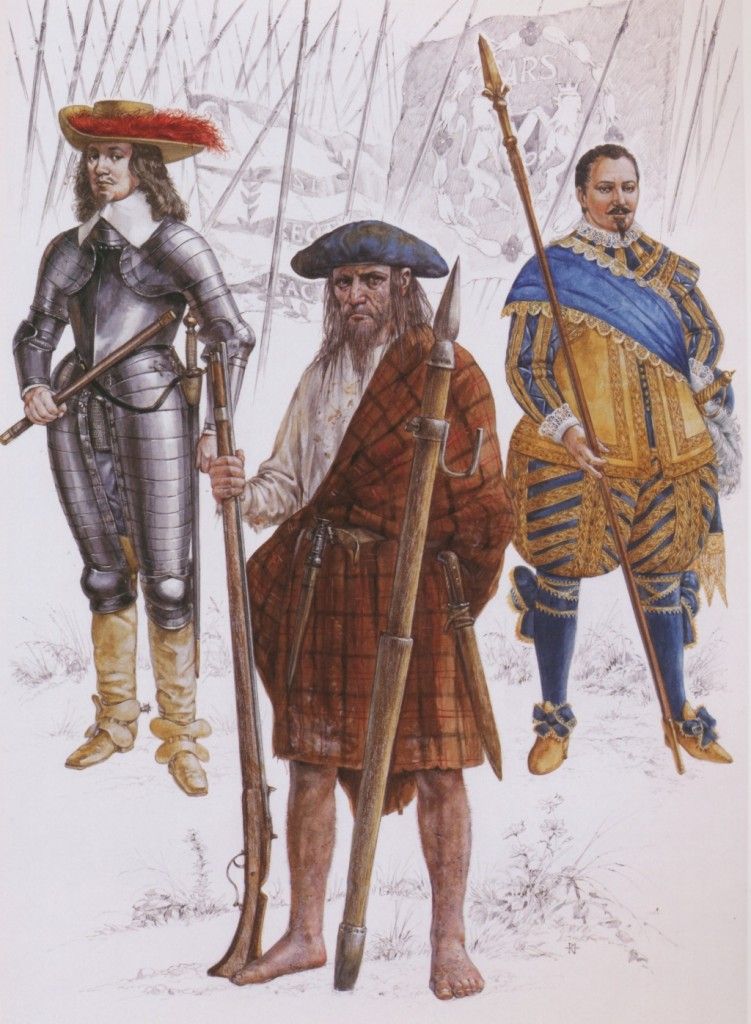

Scots in Swedish Thirty Years’ War service.

John Seton and his musketeers were still in Bohemia. After

occupying the town of Prachatice and the country as far east as Neuhaus, they

had been forced back by the advancing Imperial armies to Wittingau (now Trebon)

and had been there since September. In July 1621 only two places held out

against the Imperial forces: Wittingau and Tabor, where a Captain Remes

Romanesco was in command. Seton kept his mixed force of locals, Scots and

Germans on a tight rein, something for which he gained favour among the civil

population, although in February 1621 he had threatened to pillage the burghers

unless they provided him with some funds. That the ordinary inhabitants of

Wittingau preferred such a soldier to the kind of marauder they might have

found themselves stuck with is indicated by the fact that they warned him of an

impending Imperial attack in time to allow him to mount a surprise ambush to

thwart it. At the beginning of April he had replied in writing to one

invitation to surrender:

My dear sir, I have received from bugleman Antonia Banzio

your estimable letter in which you inform me that Tabor has returned to

obedience to His Imperial Majesty and request me to do the same. I am unhappy

that a place such as Tabor, which so bravely defended itself against your

forces, was obliged to surrender, and I may also say that the defenders

conducted themselves with valour. It is my wish to conduct myself in a like

manner, and since I have promised my king my loyalty unto death, my only

course, if I do not wish to deserve the name of liar, is to declare that, as a

testimony to my loyalty, I wager my life on the struggle. Awaiting whatever war

may bring, I remain, etc.

Seton’s defence was brave but finally futile and at last, on

23 February 1622, he surrendered on terms: the defenders and the people of

Wittingau were granted a full pardon and confirmed in their lives and

possessions. Seton later found service in the French army. His stand was not

the last hurrah of the Bohemian cause: that honour belongs to the town of

Kladsko, under the command of Franz Bernhard von Thurn, which resisted until

October.

The Spanish army, under Ambrogio Spinola, gained control of

almost all the Rhineland during the autumn of 1620, cutting off garrisons loyal

to Frederick in Frankenthal, Mannheim and Heidelberg. English troops led by Sir

Horace Vere, a thousand men who had crossed from Gravesend in May, formed the

core of the defence in the former two fortresses, while a mixed Dutch–German

contingent occupied Heidelberg. On 25 October Mansfeld relieved Frankenthal and

then crossed the Rhine to winter his troops in Alsace. As was typical of the

period, Mansfeld was content to allow his troops to live off the land, by

plundering every village and settlement they came upon. Refugees streamed into

Strasbourg to escape the pillaging soldiers, bringing with them typhus, which

wreaked its own havoc on the displaced peasants. The Imperial forces, under

Tilly, meanwhile wintered in the Upper Palatinate until campaigning resumed in

the following year. Disturbed by the presence of Spanish troops in the

Rhineland and sympathetic to their fellow-Calvinist Frederick, still in their

eyes the king of Bohemia, the leaders of the German states of Brunswick and

Baden-Durlach came out for his cause and put armies in the field. Frederick

himself joined Mansfeld at Germersheim in April, just in time to witness a

repulse of an Imperial advance at Mingolsheim. For the rest of the season the

Spanish/Imperial forces and the Protestant armies played a game of manoeuvre in

the Rhineland, shifting warily across the country, enjoying local victory and

temporary advantage. The trend, however, was against success for Mansfeld. When

the Baden-Durlach forces were cut off by the Imperialists at Wimpfen, the

mercenary commander crossed the Neckar and moved north, trying to outrace Tilly

to the Main. At Höchst, a few miles to the west of Frankfurt, the Brunswick

army suffered a crushing defeat on 20 June. In September Frederick’s capital,

Heidelberg, fell to Tilly’s army, and in November Sir Horace Vere abandoned

Mannheim. Frankenthal held out until March 1623. The whole of the Rhineland now

lay in Imperial hands.

The truce between the Netherlands and Spain had expired in

1621 and Spinola had renewed his offensive against the rebellious republic. At

this time there were two Scottish foot regiments in the Dutch army, a senior

one commanded by Sir William Brog and the other by Sir Robert Henderson.

Spinola’s first actions were to occupy the province of Jülich, on the

Dutch–German frontier, and carry out a surprise attack on the Dutch camp at

Emmerich on a Saturday morning, as a result of which Sir William Balfour was

taken prisoner for a time and had to be ransomed.

A stir was created in Scotland when it was learned that

Archibald Campbell, seventh Earl of Argyll, was recruiting for the Spanish

cause – the Privy Council noted the ‘disgust’ of the people, who were decidedly

pro-Dutch – and a Spanish galleon was attacked when it anchored in Leith Roads.

Argyll gave out that the destination of the twenty companies he sought to raise

was Sicily, to fight the Turks, but, as he had been sticking his toe into

Spanish affairs for some time, suspicions were not allayed. On a visit to Rome

in 1597 he had become an ardent Catholic and had married the daughter of a

prominent English Catholic family. In 1618 he expressed the wish to visit

Spain, ostensibly for his health but really to gather Spanish gold for his

debt-burdened estate. Spain was equally interested in the earl, as his lands in

Argyll offered men and an invasion route into Britain. In February 1619 the

burgesses of Edinburgh labelled Argyll a traitor. He took service in the

Spanish army in the Low Countries, even visiting Madrid in the autumn of 1619,

but he saw no fighting and finally changed tack and tried to restore himself to

Stuart favour. Spain was also interested in the clan Donald, the traditional

enemy of Argyll and his Campbells. A few Donald individuals, such as Sir James

Macdonald of Dunnyveg and Ranald Og, a relation of the Keppoch bard Iain Lom,

were in the Low Countries under a Spanish flag, and other Highlanders may have

been among the contingents of Irish mercenaries, but there was no large-scale

recruiting among the clans. Relatively few Scots in fact served in the Habsburg

forces in the Low Countries. There were three captains in Brussels in 1619:

James Maitland, Lord Lethington; William Carpenter and Robert Hamilton, both of

whom had been with Semple at Lier.

The composition of Spinola’s army, as estimated by the Dutch

government in August 1624, illustrates the cosmopolitan nature of the forces

now contesting across Europe. The Spanish commander had at his disposal 12,000

High Dutch [Germans], 4,000 Spanish and Portuguese, 5,600 Italians, 6,800 Walloons,

2,200 Bourguinions [Burgundians] and 3,000 English, Scots and Irish (probably

mostly the latter). With these motley thousands, Spinola initiated in 1622 a

siege of Bergen-op-Zoom, an important port and commercial town on the North

Brabant coast, where the garrison was under the command of Sir Robert

Henderson. The defending troops included English, Scots and Dutch, and it was

one of the former who noted: ‘They [the Dutch] mingle and blend the Scottish

among them, which are like Beans and Peas among Chaff. These [Scots] are sure

men, hardy and resolute, and their example holds up the Dutch.’ Early in the

siege, Henderson fell while leading a large sally against the attackers. ‘He

stood all the fight in as great danger as any common soldier, still encouraging,

directing, and acting with his Pike in his hand. At length he was shot in the

thigh.’ Henderson was carried to safety but he died soon afterwards, impressing

all who saw him with his bravery. Command of his regiment was passed to his

brother, Sir Francis.

As with the siege of Ostend some years before, the assault

on Bergen assumed the nature of ‘a publique Academie and Schoole of warre, not

only for the Naturalls of the Countrie, but for the English, Scots, French, and

Alamines [Germans], who being greedie of militarie honour, resoirted thither in

great numbers’. This notion of honour seems to have led men into acts of great

bravery, if not foolhardiness. The near-contemporary English historian William

Crosse wrote of a typical incident: ‘the English and Scottes being jealous of

their honours, and unwilling that any Nation should be more active than

themselves, resolved to assault the Spaniard works which they had made . . .

and to give them a Camisado the night following. They effected this assault

accordingly with their Musket shot and fire-balles, by which they forced the

Enemies to forsake their Trenches, after they had lost many men in the fight.’

News of the siege came to Mansfeld and he set off westward

to Bergen’s assistance. The mercenary commander’s army was not in very good

shape by this time, suffering from hunger and ill-armed, but he made good

speed. ‘When the Count departed from Manheim he was sixteene or seventen

thousand strong Horse and Foot of all Nations . . . and his Foot were all

Musketiers, there being few or no Pikes among them.’ The greater part of

Mansfeld’s force was mounted and this, combined with a lack of gear, enabled

them to move fast, via Saverne and through ‘the Straits and Fastnesses of

Alsatia, the Wildes and Woldes of Loraine’. Among them were the Scots under Sir

Andrew Gray’s command. They came through Sedan and crossed the Sambre at

Marpont on 27 August and two days later reached the small village of Fleurus,

six miles from Namur. The speed of the march had taken the Spanish completely

by surprise but they recovered sufficiently to attempt to intercept Mansfeld

here. The mercenary army battered its way through and continued towards Bergen,

finally rendezvousing with Dutch forces. By now ‘the Mansfelders were not above

sixe thousand strong that could ride or stand under their Armes, and those wre

for the most part Horse, all or the greatest part of their Foot being either

slaine in the battell of Fleurie, or disbanded in their long march out of the

Palatinate.’ But Spinola was also enduring heavy losses and the threat of a

desperate relief force on its way was enough to make him call off the siege of

Bergen.

While Mansfeld stayed with his troops, Sir Andrew Gray

crossed to England to seek further assistance from the Stuart monarchy. He

alarmed James when he was brought into the royal presence still wearing his

customary weapons – sword, dagger and a pair of pistols – but he was appointed

a colonel and prepared to lead a force of English mercenaries to rejoin his

colleagues in Europe. Before this was to happen, however, Spinola laid siege in

1624 to the town of Breda, where towards the end of the year plague cut a

swathe through the inhabitants, reducing the population by a third.

Mansfeld himself crossed the Channel in March 1624 to take

command of the new English levies for the war, with the aim of recovering the

Palatinate for Frederick and his Stuart spouse. Britain saw very high

recruitment for the continent in the latter half of 1624 – including 6,000 for

the Low Countries and 12,000 for Mansfeld. In November Alexander Hamilton was

appointed as an infantry captain and ordered to lead his men to Dover by

Christmas Eve, and presumably other contingents were given similar

instructions. Initially the plan was to land the men in France, through which

country they would be allowed to pass to join the campaign to recover the

Palatinate. At the last moment, however, fearing a counter-invasion of Spanish

troops from the Low Countries, the French withdrew permission, and Mansfeld had

no choice but to sail north to find a landing at Flushing. As the Dutch were

equally unwilling to allow such a large body of undisciplined troops ashore

under the control of Mansfeld, a commander they did not fully trust, the fleet

of ships, almost one hundred in number, was left swinging at its anchor chains

for two weeks at the end of February. The raw levies, described by William

Crosse as ‘the dregges of mankind . . . the verie lees of the baser multitude .

. . the forlorne braune and skurfe of human societie’, suffered dreadfully from

cold, hunger and thirst and began to die in their hundreds. The Dutch provided

some food but it was not enough. A few taken for dead and dumped overboard

recovered in the cold sea and were able to swim ashore to start a new life.

More commonly, corpses were washed up with all the consequent risk of disease.

Mansfeld was caught in a terrible dilemma: he could not provide for his troops

and equally he could not simply let men ashore for fear of desertion, although

a few escaped anyway and joined the enemy. One of the infantry regiments was

commanded by Sir Andrew Gray but, as the recruitment had taken place in the

south of England, there were probably few Scots among the wretched rank and

file, whose fate was as undeserved as it was typical of what could befall the

common soldier. At last Mansfeld was able to land his men, but that was not the

end of their woes.

The Dutch wanted to employ them in the relief of Breda but

after this town fell to the Spanish at the end of May they had no further use

for Mansfeld and simply wanted rid of him and his men as fast as possible.

Mansfeld led them through Brabant to Cleves on the Dutch–German border, losing

men daily through desertion. By this time, the unlucky mercenary commander had

only about half of his original strength but he struggled on against tremendous

odds, betrayed by those who had undertaken to supply him. Back in Scotland, the

Privy Council issued a warrant to Sir James Leslie to travel about the country

to levy another 300 foot soldiers to serve under Mansfeld. Leslie’s recruits

eventually rendezvoused with Mansfeld’s main body in north-western Germany. At

last, at the end of the year, the survivors found some food and rest in the

bishopric of Münster, around the town of Dorsten. Before long, though, Mansfeld

had to lead them further north, through Lingen, Haselünne on the River Hase,

Cloppenburg and at last to Emden, extorting supplies as he went, his men

passing through each district like a swarm of locusts. The prospect of having

to feed mercenaries led the citizens of Emden to open sluice gates and to flood

land in an effort to deter them, but this only angered Mansfeld, who had

endured so much in the cause he fought for, and he held the town to ransom for

130,000 reichsthaler, until finally the King of Denmark stepped in to settle

matters and provide a degree of security for the bedraggled remnants of the

army.

The fate of Sir Andrew Gray remains obscure but he seems to

have remained in the Netherlands before returning to Scotland and then, in

1630, going to France. With a band of followers, John Hepburn went north to

offer his services to Gustavus Adolphus; he was welcomed and made a colonel in

command of a regiment. Hepburn was to prove to Gustavus Adolphus that the royal

judgement had not been misplaced, and opened a new chapter in the story of the

Scottish soldiers in Europe.