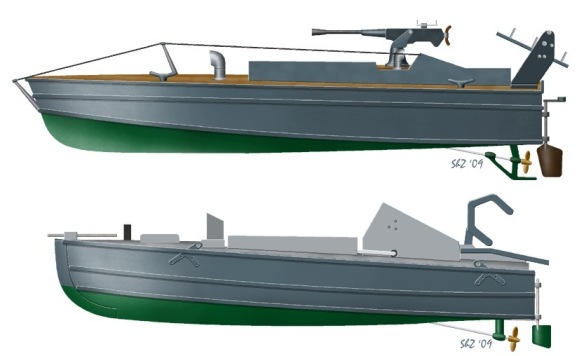

The Maru-in [top] and Shinyo Explosive Motoboats

Early Maru-re boats had the depth charges mounted

alongside the pilot’s compartment. The depth charges could be released manually

or by ramming the prow into the target ship. Division of Naval Intelligence, ONI

208-J Supplement No. 2, Far-Eastern Small Craft, March 1945, p. 31.

In March 1944, the Imperial Japanese Army’s Warship Research

Institute at Himeji, near Kobe, was directed to devote considerable effort to

the development of “special (attack) boats”; in other words, suicide boats. One

month later, the Imperial Japanese Navy issued a similar directive concerning

suicide weapons of all kinds to its departments of warship and aircraft

production. It is certain, however, that the employment of suicide weapons had

been under consideration since at least mid-1943, and that the activities of

early 1944 merely represented official sanction for such weapons; for the first

suicide boat units of both Army and Navy were being deployed for operations as

early as August-September 1944. Thus, as in the case of the kaiten torpedo and

the ohka piloted-bomb, the design and construction of a suicide weapon

considerably predated “official” references to it.

■ The

Army’s Suicide Boats

The Army’s interest in EMBs was provoked by the inability of

its aircraft, in the face of Allied air superiority, to strike effectively at

the most vulnerable element of the Allied amphibious landing forces – the

landing ships. Seeking a method of attacking at night and hitting the

transports while they lay off the beaches, the IJA adopted the concept of the

maru-ni (“capacious boat”) units. The name reflected a reluctance to be openly

committed to a suicidal weapon; the term renraku-tei (“communications boat”)

was also used. (The Navy displayed less reluctance to acknowledge the weapon’s

true nature, calling its EMBs shinyo, “ocean-shakers” or “sea-quake” boats.)

But the Army’s commitment to suicide tactics became

increasingly overt after the fall of Saipan in June 1944, when Imperial General

HQ issued a directive called Essentials of Island Defence. This stressed the

importance of attacking invasion shipping during the approach to the beaches

and the unloading phase. The Army Air Force was ordered to concentrate its

attacks on transports, ignoring escorts, and to employ low-level “skip-bombing”

techniques and, if necessary, suicide dives. Suicidal surface craft were to

strike at transports at anchor. The Navy’s need for suicide boats, on the other

hand, stemmed largely from its pre-war neglect of conventional MTB development

and its inability, in wartime conditions, to produce small, fast attack craft

comparable to the US Navy’s PT-boats.

■ The

Maru-ni Explosive Boat

The Army’s maru-ni was a one- or two-man boat of wooden

construction, a little over 18ft (5.4m) long and displacing about 1.6. Power

was provided by a rebuilt automobile engine, an 80shp unit giving a maximum

speed of 25–30kt (28–35mph, 46–56kmh). Its armament consisted of one 441lb

(200kg) depthcharge (or sometimes two smaller charges) held on dropping gear at

the stern.

Theoretically, the maru-ni was not a suicide boat. An Army

manual stated that the recommended method of attack was to make a high-speed

run on the target; release the depthcharge, fuzed to detonate in about 4

seconds, alongside; and then head away before the explosion. In practice, the pilot

obviously had little chance of surviving the attack and, according to the

testimony of former members of EMB units, most pilots elected to ensure a hit

by making ramming attacks.

The Army made an attempt to produce a truly high-speed

attack craft by fitting the Type N-1 maru-ni with booster rockets which could

be cut in on the last few hundred yards to the target. In experiments made at

Ujima, Hiroshima, late in 1944, rocket-assisted boats achieved speeds of

50–60kt (57–69mph, 92–111kmh) over short distances. However, since only two or

three such boats were built, it is obvious that they were deemed unsuitable for

operational use.

■ The

Shinyo Explosive Boat

Most accounts by western writers of Japan’s special attack

forces make little mention of the EMBs, and often fail to differentiate between

the maru-ni of the Army and the Navy’s shinyo. In fact, although the dimensions

and performance of the boats was much alike, there were significant differences

in armament.

The Type 1 shinyo was a one-man boat built largely of

plywood, although a few were of metal construction. It was 19.7ft (6m) long and

displaced 1.35 tons (1.37 tonnes). It was powered by a 67bhp internal

combustion engine, supposedly giving a maximum speed of 26kt (30mph, 48kmh) and

an action radius of 105nm (121 miles, 194km) at high speed. In fact, the use of

reconditioned automobile engines meant that the shinyo’s power units were

notoriously unreliable: the former commander of a shinyo squadron states that

none of his Type 1 boats was capable of more than 23kt (26.5mph, 42.5kmh)

unladen, or more than 18kt (21mph, 33kmh) when carrying a warhead.

The shinyo’s warhead consisted of a 551–661lb (250–300kg)

explosive charge. This was usually rigged to explode only on impact, when the

crushing of the boat’s bows completed a simple electrical circuit. On later

boats, a trigger or switch in the cockpit could be used to detonate the charge,

thus in effect turning the pilot into a human bomb. Most shinyo built after

January 1945 incorporated two RAK-12 rocket-guns, crude wooden projectors

mounted on either side of the cockpit. Each discharged a single 4.7in (119mm)

projectile weighing 49.5lb (22.4kg). These were intended to be fired at close

range, liberating a shot-gun scatter of metal slugs that would be effective

against the target ship’s 40mm and 20mm gunners in their lightly-protected or

exposed positions.

One boat in each squadron of 40–50 shinyo was to be crewed

by two men – the squadron commander and his pilot. It was intended that in a

mass sortie the commander should bring up the rear, observing the attacks made

by his men and, if possible, assisting them with covering fire from a machine

gun on a swivel mounting just forward of his cockpit. (The 13.2mm Type 93 heavy

machine gun was specified, to be mounted on the Type 1/Improved 4 and the

larger Type 5 boats.) Having seen all his men strike home, the commander would

then order the pilot of his own boat to attack and both men would perish

together.

■ The

First Suicide Boat Squadrons

By the summer of 1944, both the Army and Navy had formed and

were beginning to deploy suicide boat squadrons. The former commander of one of

the IJN’s first EMB squadrons related his own experience to the author. In

August 1944, having expressed his willingness to undertake hazardous duty (its

exact nature apparently unspecified, although he was in no doubt that he was

volunteering for suicidal operations), he was posted to Yokosuka Naval Base and

found on arrival that he had been given command of Shinyo Squadron No 6 (SS 6).

The Squadron – 48 shinyo and some 200 men – had already been formed. The shinyo

pilots, some 50 officers and petty officers, were volunteers for special duty;

the supporting personnel had simply been assigned in the usual way.

The early shinyo squadrons and maru-ni seem all to have been

made up in this way; that is, with volunteer pilots who had been made aware

that their duties would be “special”, ie, suicidal; and it must be remembered

that the Imperial Rescript concerning military conduct, the expression of the

Emperor’s will, assumed that Japanese servicemen were prepared to sacrifice

their lives at any moment should their duty demand it. In any case, all EMB

personnel seem to have accepted their postings with equanimity.

Although a three-month training period in small-boat

handling, mechanics and attack techniques was prescribed for EMB units, the

early squadrons were expected to fit their training schedules into a series of

rapid deployments necessitated by the urgent need for their services for the

defence of the Philippines, Okinawa, Formosa and Hainan Island. In September

1944, Shinyo Squadrons 1–5 were sent to Chichijima and Hahajima in the Bonin

Islands, while Squadrons 6–3 were ordered to the Philippines. Thus, it is

obvious that even before the “official” inception of EMB training (in

October-November 1944), some 650 pilots and 2,500 support personnel were

available for the Navy’s shinyo squadrons alone; while the scale of maru-ni

deployment in the Philippines at this time suggests that the Army’s numbers

were at least as great.

The semi-secrecy with which the early squadrons were formed

led to problems. The commander of SS 6 found it hard to fill his unit’s

equipment lists because “the nature of my squadron was kept so secret that the

relevant supply departments knew nothing about us”. Unable to get personal

weapons for his pilots through the proper channels, he made an unauthorized

flight to Tokyo and “by all but threatening an officer at the Navy Ministry”

obtained 50 revolvers and a supply of ammunition. On the trip back, he

encountered Vice-Admiral Sentaro Omori, overall commander of torpedo boat

training, who had a fearsome reputation as a disciplinarian. Questioned, the

officer confessed his breach of regulations – “and Admiral Omori wept! ‘Do they

really have to make a commander who may go to his death at any moment worry

about this sort of thing”?’ he said”. But the sentiments expressed by

Vice-Admiral Komatsu, commander of Sasebo Naval Base, were more conventional:

he ended his rousing address to an outward-bound EMB squadron with “a

thunderous shout of ‘Go, then, into battle!’” – being careful not to use the

Japanese form of speech that implies “go – and return again”.

■

Deployment of the EMBs

The deployment of shinyo and maru-ni units in the

Philippines before and during the American landings at Leyte that began in

October 1944 was as follows:

Shinyo Squadrons 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13, with a total

strength of 300 Type 1 boats, at Corregidor;

Advanced Combat Units (Army) Nos 11 and 12, with a total

strength of 200 maru-ni, around Lingayen Gulf, west-central Luzon;

Advanced Combat Units Nos 7, 9 and 17, with a total strength

of 300 maru-ni, around Lamon Bay, southeast Luzon;

Advanced Combat Units Nos 14, 15 and 16, with a total

strength of 300 maru-ni, around Batangas Bay, southern Luzon. Thus, a total of

300 shinyo guarded the island fortress of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila

Bay, while 800 maru-ni were deployed to cover the most likely invasion beaches.

In addition, two torpedo boat squadrons, equally ready for conventional or, if

necessary, suicidal operations, were available:

Torpedo Boat Squadron No 25, with 10 boats, based on Cebu

Island, west of Leyte;

Torpedo Boat Squadron No 31, with 10 boats, based at Manila.

The hurried deployment of the early EMB units had caused

problems. On 1 October 1944, SS 6, which had been transported to Manila aboard

two oil tankers, was ordered to be ready for action within two weeks. Its

pilots had received no practical training: “our boats were still crated up, as

they had been received from our workshops. It was highly unlikely that we could

get full power from them without a proper working-up period; and loading the

explosive warheads by hand-winch would take about 10 days”. In response to his

protests, SS 6’s commander was assigned 100 more support personnel, a

miscellaneous collection of survivors from sunken ships: “all in short-sleeved

shirts and shorts, with white kerchiefs round their heads and not a weapon

between the lot of them. They were like primary schoolchildren filing out on to

the playground for sports day!”

Although SS 6 had reached Manila intact, considerable losses

were suffered by other EMB units en route to the Philippines, whence a total of

more than 1,000 shinyo and maru-ni was dispatched in September–October 1944.

Some transports were sunk; accidents were caused by the instability of the

boats’ explosive charges and the unreliability of their engines; and men

succumbed to tropical diseases. The greatest danger came from air attacks: to

escape these, while awaiting the expected Allied invasion, SS 6 was posted from

its base at Zamboanga, western Mindanao, to Sandakan in North Borneo. The

Allied landing at Leyte on 17 October 1944 trapped SS 6 at Sandakan for the

rest of the war. Establishing a base on a small, swampy island in Sandakan Bay,

the Squadron trained for the attacks it would never have the chance to make;

and by August 1945 more than two-thirds of its personnel had died from tropical

diseases aggravated by rough living and semi-starvation.

The Army’s maru-ni units experienced similar vicissitudes.

Captain Takahashi’s Advanced Combat Unit No 12 (ACU 12; the Army units were

sometimes called “Sea Raiding Battalions”); formed at Etajima on 1 October 1944

with a strength of 100 boats, took ship for the Philippines only two days

later. By 15 November, after suffering the loss of several boats in a typhoon,

it had established a base just north of San Fernando, on Lingayen Gulf, central

Luzon. Thus, such training as was possible had to be carried out in the combat

zone where, while exercising on 15 December, the unit lost several boats to air

attack.

On 26 December, Takahashi was ordered by Major-General

Nishiyama’s 3rd Division HQ to move ACU 12’s base from San Fernando to Sual in

the southwest of Lingayen Gulf. Because only one small transport vessel was

available, many of the maru-ni had to make the voyage of some 20nm (23 miles,

37km) under their own power, and two boats and their crews were lost on the

way. The movement was not completed until 4 January 1945, only two days before

the US Navy’s Task Group 77.2 entered Lingayen Gulf to begin a pre-invasion

bombardment. Although both kamikaze and conventional aircraft struck hard at

Vice-Admiral J. B. Oldendorf’s battleships, cruisers and destroyers, Japanese

forces ashore suffered severely. Nine of ACU 12’s pilots were killed by naval

gunfire on 7 January and as many more on the morning of 9 January, when US

landings began. On that day, 3rd Division HQ ordered ACU 12 to attack Allied

invasion shipping.

■

Disaster at Corregidor

The Imperial Japanese Navy had hoped to have the honour of

launching the first EMB attack, but this was prevented by an accident of a kind

all too common. On 23 December 1944, Japanese commanders at Corregidor were

warned that major Allied warships were moving north in coastal waters from

Mindoro. Shinyo Squadrons Nos 7–3, based at Corregidor under the overall

command of LtCdr Oyamada, were ordered to readiness. In the hurried

preparation, the engine of one boat of Lt Ken Nakajima’s SS 9 caught fire.

Since the Squadron’s boats were packed tightly together in the cave chosen as

base, the fire quickly spread, detonating the boats’ warheads in a chain of explosions

that wiped out all the shinyo and most of their pilots. No sortie could be

made.

The frequent engine fires and failures of the shinyo (the

maru-ni seem to have suffered less from such accidents) had more than one

cause. Japan had failed to develop an efficient small-boat engine, and the

automobile engines which powered the shinyo were not purpose-designed and had

often had hard usage before conversion. And although petrol engines are better

suited to small, fast craft than are diesels – giving a better power-to-weight

ratio and being capable of running at full power for longer periods – they are

also more prone to take fire and require much more careful maintenance. Since

time and facilities for training shinyo personnel were so limited, skilled maintenance

was not always available.

As at Corregidor, EMB units facing the constant threat of

air attack often established their bases in natural caves or pens blasted from

rock or coral. When engines were run up in such cramped, semi-enclosed

quarters, the air became so thick with petrol vapour that any chance spark

might trigger off a holocaust. A former shinyo squadron commander states:

“Most personnel had no combat experience at all before they

were called upon to sortie, and it is not surprising that young, inexperienced

seamen should have neglected some vital precaution when preparing their boats

in such circumstances. The Imperial Navy, it must be admitted, provided very

little training in fire precautions, and fire-fighting equipment for shinyo

squadrons was practically non-existent.”

Although Japanese officers consulted by the author had no

criticisms of the explosives supplied for their boats, most Allied authorities

agree that Japanese explosives were not of a high degree of stability,

especially when exposed to excessive heat or humidity.

Date: 10 January 1945

Place: Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, Philippines

Attack by: Maru-ni EMBs, Imperial Japanese Army

Target: Allied invasion shipping

During daylight on 9 January, some 70,000 US troops, meeting

little initial opposition, established a beachhead at Lingayen. The invasion

transports and their escorts, commanded by Vice-Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson,

lay close inshore, ready to recommence landing men and materiel next morning

and meanwhile on the alert for kamikaze air attack. But the major threat was to

come from the sea: Captain Takahashi of the Imperial Japanese Army was ready to

launch the first and most successful of the mass suicidal surface attacks.

Takahashi had at readiness about 40 maru-ni of ACU 12, most

of them belonging to Lt Womura’s 3rd Company, reinforced by some 50 boats of

ACU 11. Since the Army’s maru-ni units were generally much larger than the

Navy’s shinyo squadrons – with as many as 200 pilots and 600 support personnel

to a unit of about 100 boats – it was not uncommon for a single maru-ni to go

into action with a crew of up to four men, rather than the “official” one or

two. Personal honour led supernumary pilots, and even support personnel, to

demand their chance of a glorious death in battle. This was the case at

Lingayen, where US combat reports spoke of EMB’s crews attacking with small

arms and grenades as well as depth charges. The same reports suggest that a

number of small MTBs may have taken part in the attack – but the majority of

the boats committed were maru-ni, carrying either one 441lb (200kg) or two

265lb (120kg) depth charges and with up to four crewmen armed with light

machine guns, rifles and pistols, hand grenades and Molotov cocktails.

A Japanese officer denies US reports that the maru-ni

incorporated a device that allowed the rudder to be locked in position, so that

the crew could take to the water after setting the boat on a collision course:

“Imperial General HQ and the Army and Navy staffs wished for

escape provisions of this kind to be made on the maru-ni and shinyo – but in

most cases the pilots themselves refused, saying that this was not necessary. I

believe that this stemmed from their personal sense of honour.”

The maru-ni sortied from Sual, some 5nm (6 miles, 9km)

northwest of the Lingayen beaches, before 0300 on 10 January. They approached

the Allied anchorage with engines throttled down, hoping to evade the screen of

escorts and strike at the soft-skinned transports. The first alarm appears to

have been given by the radar watch aboard the destroyer USS Philip (Cdr J. B.

Rutter), when three “blips” too small to be aircraft registered at 0320. The

night was too dark for unassisted lookouts, but in the glare of starshell a

number of small boats were spotted. The maru-ni pilots speeded up to attack.

At 0353 the battleship USS Colorado picked up a TBS appeal

from the 1,625-ton (1651 tonne) tank landing ship LST-925: “… damaged by

enemy torpedo boats … taking on water … send rescue boats”. At least three

maru-ni had dropped depth charges alongside LST-925, holing her beneath the

waterline and knocking out her starboard engine. These three boats had not

rammed their target but had executed a drill-book attack: coming in at about

20kt (23mph, 37kmh) from astern – one boat to port, one to starboard, and one

some 50–100yds (46–90m) to the rear backing up; dropping depth charges on a

four-second fuze as close as possible to the ship’s most vulnerable areas –

amidships, below the stacks or at the stern to damage propellers and rudders;

and then veering sharply away.

Most of the maru-ni, however, made straightforward ramming

attacks to ensure that their depthcharges exploded directly beneath their

targets. Such an attack was made on LST-1028: explosions stove in her bottom

and sent water pouring into her engine compartments. Near the two stricken

LSTs, the 6,200-ton (6300 tonne) transport War Hawk was rammed by a single

maru-ni. Signalling that his ship had been “torpedoed”, her skipper gave the

order to abandon ship; but War Hawk, with a 12ft (3.6m) gash in her side and 73

casualties, survived.

Soon after 0400, when a general warning of attack by “torpedo

boats” was given throughout the Allied fleet, USS Philip narrowly escaped

damage when a maru-ni racing in on a collision course exploded only 25yds (23m)

away when raked by 20mm fire. The Allied ships were hampered in their evasive

manoeuvring by the crowded anchorage (two transports and an LST were damaged in

collisions) and their fire against the diminutive attackers was limited by the

danger of hitting their own ships. The US destroyers Robinson and Leutze,

engaging a group of maru-ni between 0415 and 0445, were rarely able to move at

more than 5kt (5.75mph, 9.25kmh), and the small craft pressed so close that

only light automatic weapons could be brought to bear. The attack was beaten

off, but Robinson sustained superficial damage from a maru-ni exploded by

gunfire at close quarters. By that time, the general warning had been extended

to include midget submarines and “suicide swimmers”, as well as torpedo boats

and EMBs.

By about 0500, the surviving maru-ni had withdrawn. They had

suffered heavily: about 45 boats were lost and ACU 12 was incapable of further

operations. Relying on explosions reported by shore observers, Japanese

official sources claimed that 20–30 US ships had been sunk or seriously

damaged. In fact, apart from the ships already mentioned, LCI(M)-974 and

LCI(G)-365 – 246-ton (250 tonne) infantry landing craft converted for duties as

mortar and gun/rocket armed escorts respectively – had been sunk; LST-610 and

LST-925 had been seriously damaged; and seven transports had suffered lesser

damage. The results were serious enough for the US Navy immediately to expedite

the northward deployment of PT-boat squadrons from the southern Philippines and

significantly to increase the number of escorts assigned to guard attack

transports’ anchorages.

■

Suicidal Conduct by Survivors

From the conduct of Japanese survivors found in the water

after the attack stemmed the legend of the “suicide swimmers of Lingayen” – of

naked Japanese swimmers with explosive charges strapped to their backs being

mopped up by boatloads of US sailors armed with knives and small arms. (It is

true that the IJN trained teams of suicidal swimmers and frogmen, but these

were not committed at Lingayen.) The legend originated in the intransigence of

the maru-ni survivors. For example, the destroyer transport USS Belknap lowered

a boat to rescue two Japanese afloat on a piece of wreckage – and had to

machine gun both when they attempted to fling grenades at their would-be

rescuers. Eleven more survivors were killed under similar circumstances that

same morning by Belknap alone, and many more by other ships.

Resistance to rescue by Japanese who preferred suicide to

capture was nothing new. Of many incidents, one of the most striking occurred

off New Ireland in the Bismarck Archipelago on 22 February 1944, when the IJN’s

750-ton (762 tonne) salvage and repair vessel Nagaura, mounting two 25mm guns,

attempted to engage the five US destroyers of Captain Arleigh A.

(“Thirtyone-knot”) Burke’s Desron 23, and was blown apart by 5in (127mm) fire.

Of some 150 survivors, about half allowed themselves to be rescued (and within

one day were volunteering to act as ammunition carriers during the bombardment

of a Japanese-held island!) Of the remainder, some cut their throats while

others, unarmed, deliberately drowned themselves, sometimes diving many times

before the determination to die triumphed over the instincts of

self-preservation.

Similar suicidal determination was displayed by survivors of

an action on 26 March 1945, when four British destroyers led by HMS Saumarez,

assisted by B-24 bombers, sank two Japanese transports and their escorts, the

440-ton (447 tonne) submarine-chasers Ch 34 and Ch 63. Only 53 survivors from

the four ships were picked up, of whom one subsequently hanged himself aboard

HMS Volage; the rest simply swam away to drown. One man swam to HMS Saumarez

carrying a 25mm shell and, hanging on to the rescue net, hammered on the

destroyer’s side in a desperate attempt to detonate it until he was clubbed

into the sea.