In the event, Hobart did not get to see the fruits of his

labour in action. In July 1939 Gordon-Finlayson was replaced as General Officer

Commanding-in-Chief by Lieutenant-General Henry Maitland Wilson, who had

attended the same course as Hobart at the Staff College at Camberley in 1920.

Initially their relationship was good, and Wilson praised the performance of

the Mobile Division after attending the final phase of a week long exercise at

the end of July. Things deteriorated rapidly following another divisional

exercise three months later however, when a series of misunderstandings and

missed communications ended in a stand up argument and a public dressing down

for Hobart. Wilson followed this up on 10 November 1939 with a request that

Hobart be relieved, and Wavell complied after a personal interview with Hobart

four days later; he was replaced by Major-General Michael O’Moore Creagh MC.

The news does not appear to have gone down well with Hobart’s men, for

according to his biography they lined the road from Hobart’s HQ and cheered him

all the way to the airstrip where he began his journey back to Britain.

The relief of such a technically proficient officer during

such perilous times was certainly curious, and Hobart’s biography suggests that

it was the upshot of long standing grudges against Hobart in the army’s upper

echelons, and that it was accomplished via improper use of confidential

competence reports. While Wavell’s decision is far more likely to have been

motivated by the need for harmonious working relationships than resentment over

an incident during an exercise in 1934, subsequent events do support the grudge

theory to some extent. Despite assurances to the contrary from the Chief of

Imperial General Staff General Sir Edmund Ironside, Hobart was retired from the

army with effect from 9 March 1940, and interestingly the British Official

History published in 1954 makes no mention of Hobart at all. Be that as it may,

this was clearly a waste of talent and expertise, but fortunately it was not

the end of the story. In August 1940, while serving as a Lance-Corporal in the

Chipping Camden detachment of the Local Defence Volunteers, Hobart took a

position with the Ministry of Supply linked to tank production. He came to

Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s attention at a conference at Chequers, and

by early 1941 he had been returned to the army active list and given the task

of forming the 11th Armoured Division. He was then given the same task with

regard to the 79th Armoured Division in March 1943, and oversaw the development

of a host of specialised armoured vehicles that played an important role in the

D-Day invasion on 6 June 1944.

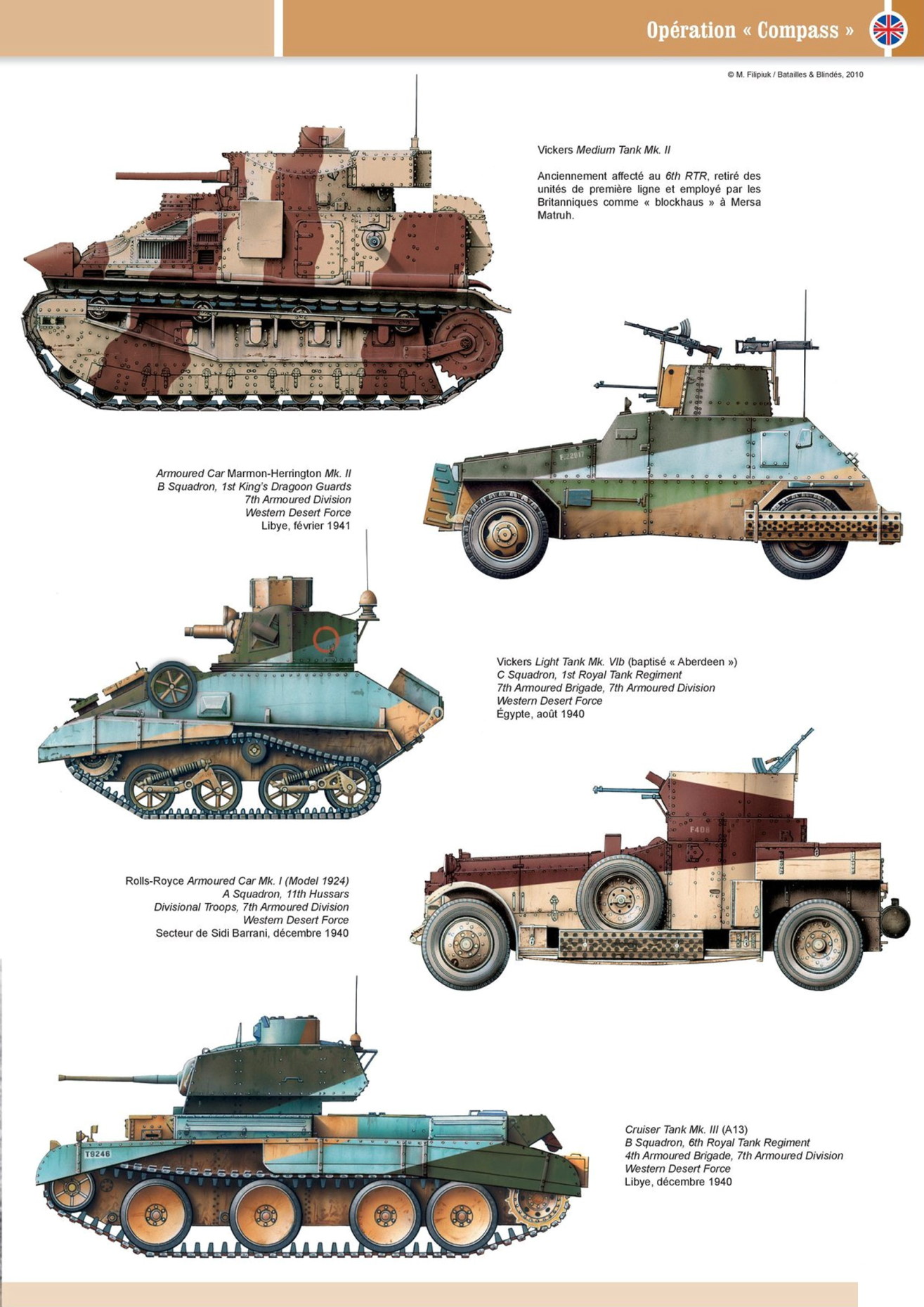

Wavell’s plan in the event of war with Italy was to seize

the initiative from the outset by using the Western Desert Force to attack

Italian border posts in Libya and dominate the border zone as far west as

practicable. This was intended to forestall or at least delay any Italian

attack into Egypt, with the object of denying it the coastal town of Mersa

Matruh, which housed the terminus of the coastal railway to Cairo. Thus the 7th

Armoured Division, as the Mobile Division had been renamed on 16 February 1940,

had been deployed in the area of Mersa Matruh and Maaten Baggush, where

O’Connor had established Western Desert Force HQ on 8 June 1940. The division

had been expanded, and its constituent formations had also been renamed and

reorganised. The Light and Heavy Tank Brigades had become the more balanced 4th

and 7th Armoured Brigades, made up of the 7th Hussars and 6th Royal Tank

Regiment (RTR) and 8th Hussars and 1st RTR respectively. The Pivot Group,

renamed the Support Group, was made up of the 1st KRRC, the 2nd Battalion, The

Rifle Brigade and the 4th RHA, while the 3rd RHA and 11th Hussars were grouped

together as Divisional Troops.

As soon as news of the Italian declaration of war was

received O’Connor ordered the 11th Hussars up to the border, followed at around

a forty mile interval by the 7th Hussars Light and Cruiser Tanks and the

Support Group. At around the same time Collishaw moved No. 202 Group HQ up to

one of his forward airfields and ordered all aircraft to be made ready, but

confirmation came too late to commence operations before nightfall on 10 June

1940. Dawn sorties by reconnaissance Blenheims from No. 211 Squadron to the

major Regia Aeronautica base at El Adem found aircraft parked in the open, and

eight Blenheims from No. 45 Squadron made the first of several attacks shortly

afterward. By the end of the day the RAF had destroyed or damaged eighteen

Italian aircraft for the loss of two Blenheims and three damaged. On the ground

the 11th Hussars reached the border in the evening of 11 June, and their Rolls

Royce and Morris armoured cars crossed the border at four points between Forts

Capuzzo and Fort Maddalena, after breaching the Italian concertina wire by the

simple expedient of flattening the picket posts with their vehicles and then

dragging the wire aside or churning it into the sand. At 02:00 on 12 June a

small detachment from B Squadron guarding one of the gaps shot up an Italian

truck on the path paralleling the border, capturing fifty-two very surprised

Italians who had not been informed that hostilities had commenced; the

occupants of another truck captured near Fort Capuzzo told a similar story.

This set the tone for the next few days and nights and once

the Support Group closed up and took responsibility for dominating the area

immediately inside the Libyan border, the 11th Hussars pushed their activities

further into Italian territory in company with elements of the 7th Hussars. On

14 June the Italian posts at Fort Maddalena and Fort Capuzzo were captured, the

former without a fight by A Squadron, 11th Hussars; the garrison of five

Italians and thirteen Libyans ran up the white flag on their approach. Fort

Capuzzo also surrendered after an RAF attack that failed to actually hit the

Fort and a few of the 7th Hussars’ Cruiser Tanks had put some 2-Pounder armour

piercing rounds through the walls. The heaviest fighting of the day took place

at Sidi Azeiz, the target of a subsidiary probe by a mixed force from the 7th

and 11th Hussars supported by an RHA battery. The 11th Hussars tanks

successfully overran outlying Italian infantry positions protecting the post

but ran into a minefield that knocked out three tanks and stranded several

more, which then came under accurate Italian artillery fire. When the

accompanying RHA battery proved unable to suppress the Italian guns, which were

deployed on the reverse slope of a ridge, the British force withdrew in the

afternoon. While all this was going on six Italian CV33 tankettes approached a

screening position held by elements of B Squadron, 11th Hussars, but retired at

speed when one of their number was knocked out with a Boys anti-tank rifle,

leaving the crew to be made prisoner.

By 16 June the 11th Hussars had expanded their marauding to

the north, and C Squadron had set a successful ambush on the stretch of the Via

Balbia linking Tobruk with Bardia using a felled telegraph pole as a roadblock.

Over the course of the morning this netted a number of Italian trucks and a

Lancia car carrying Generale di Corpo Lastucci, senior engineer officer to the

10° Armata, his aide-de-camp and two female companions, one of whom proved to

be pregnant. Lastucci carrying detailed plans of the Italian defences at Bardia

and, in one of those curious coincidences of war, was also a personal

acquaintance of Major-General O’Connor; the latter saw Lastucci briefly en

route to captivity along with his pregnant companion, who subsequently gave

birth in Alexandria. The same day saw the largest engagement of the period at

Nezuet Ghirba, south-west of Fort Capuzzo, when C Squadron 11th Hussars ran

into an Italian column of thirty trucks, four artillery pieces and twelve CV33

tankettes divided equally between the front and rear of the column. According

to orders subsequently found on the body of the Italian commander, a Colonello

D’Avenso, the column was part of a force – another larger column had also been

spotted by British scouts – tasked to ‘destroy enemy elements which have

infiltrated across the frontier, and give the British the impression of our

decision, ability and will to resist’, but things did not turn out quite that

way.

On being somewhat impetuously attacked by two Rolls Royce

armoured cars after a communications failure, the Italians made no attempt to

find cover or occupy defensible terrain but simply formed their trucks into a

square formation with their artillery pieces at the corners while the CV33

tankettes patrolled outside. The formation came as something of a surprise to

Lieutenant-Colonel John Combe, the commander of the 11th Hussars, when he

arrived on the scene and was presumably a drill developed to counter

unsophisticated colonial enemies. Whatever its provenance, the tactic proved of

little value against better armed and more adept opponents and having summoned tank

and artillery reinforcements, the British went on the offensive. The Italians

may have been tactically inept but they were not short of courage. Three CV33s

had been knocked out in the initial stages of the action, and seven of the

remainder mounted a counter charge to protect their infantry from the oncoming

British tanks, but their inadequate armour was not up to the task and they were

knocked out in quick succession. When the Italian square broke under the

British assault the last surviving CV33 was destroyed in an attempt to ram an

A9 Cruiser tank and the Italian artillerymen also fought to the last, being

machine-gunned as they tried to bring their guns to bear on the British tanks.

Only around a hundred Italians and a dozen trucks survived to be escorted back

through the frontier wire to captivity in Egypt; their opponents did not incur

a single casualty.

O’Connor’s men thus achieved Wavell’s objective of throwing

the Italians off balance and dominating the Libyan side of the frontier, but

the operational tempo soon began to tell on machines and especially men alike.

According to the history of the 11th Hussars the first two weeks of hostilities

were considered by some to be the most intensive of the entire war. The lack of

sleep, insufficient water and short and monotonous rations were bad enough in

themselves; it was not unusual for exhausted crewmen to simply collapse to the

floor of their vehicles, and bully beef and biscuits were literally the only

rations available for days on end. All this was exacerbated by the onset of the

khamsin on 19 June, with 25 June being recorded as the hottest day the 11th

Hussars had experienced to date. The heat was so intense that the armoured cars

were too hot to touch, and the unfortunate crews were obliged to dismount and

seek shelter beneath them. The severity of the conditions is well illustrated

by an episode involving the second-in-command of the 4th Armoured Brigade who,

during a reconnaissance for a joint operation to take the Italian-held oasis at

Jarabub, refused to subject his tanks to such furnace-like conditions and

insisted that they made operations impossible; the same officer collapsed later

when informing Lieutenant-Colonel Combe that he intended to get the armoured

car unit withdrawn.

By July the strain was becoming too much, and when C

Squadron 11th Hussars lost four men dead and fourteen captured in an abortive

action O’Connor intervened. The 11th Hussars were thus ordered to reduce their

activities to allow half its strength to be resting on the coast at Buq Buq,

while the 4th Armoured Brigade was rotated out of the frontier zone in its

entirety and replaced by the 7th Armoured Brigade. Thereafter the screening

force reverted to a watching brief, and kept the British commanders informed of

the Italian reoccupation of Fort Capuzzo, and their pre-invasion build-up and

reconnaissance activity in the vicinity of the latter, Sidi Omar and Bardia.

This prompted a further reorganisation to face the developing threat, and on 13

August all the British armour was withdrawn to Mersa Matruh, leaving

responsibility for the frontier zone to the 7th Armoured Division’s Support

Group, commanded by Brigadier W.H.E. Gott; the latter was instructed to

maintain close watch on the enemy, especially in the area between Sollum and

Maddalena. To achieve this, the Support Group had received reinforcements

including the 3rd Battalion The Coldstream Guards, the 3rd RHA, a section from

the 25/26th Medium Battery R.A., two anti-tank batteries, a detachment of Royal

Engineers and the 7th Hussars’ Cruiser Tank Squadron.

The reorganisation was in line with O’Connor’s defensive

plan, which required the Support Group to conduct a fighting withdrawal to

Mersa in preparation for an armoured thrust from the desert to the south against

the Italian’s flank, to cut off and hopefully starve their vanguard into

submission. This was a little less wishful than it appears, for on 10 August

1940 the War Office had presented Churchill with a list of the units and

equipment allocated for despatch to Egypt as soon as shipping and escorts could

be procured. The list included forty-eight 2-Pounder anti-tank guns, the same

number of 25-Pounders, twenty Bofors guns and over million assorted rounds of

ammunition. Perhaps more importantly, the list also included the 3rd King’s Own

Hussars and the 2nd and 7th Royal Tank Regiments, equipped with Light, Cruiser

and Infantry Tanks respectively.

O’Connor was obliged to put his plan into effect at dawn on

13 September 1940, when Graziani finally launched his invasion. It began with

the bombardment and seizure of Musaid via the gaps torn in the frontier wire by

the 11th Hussars on the night of 11–12 June, followed by an advance on Sollum

and the adjacent airfield. All this was observed by a platoon from the 3rd

Battalion The Coldstream Guards which primed mines emplaced along the tracks

leading east as it withdrew, and in Sollum proper the Royal Engineer detachment

attached to the Support Group busied themselves demolishing buildings and

supply dumps. The damage inflicted by the mines was compounded by the RHA,

which accurately dropped salvos of shells on the advancing Italian transport

using the reflections from their windscreens as a target indicator. British

artillery also shelled the large traffic jams that built up on the trails

leading down to the Halfaya Pass that cut through the Sollum Escarpment and

provided access to the coastal plain to the east. The 1st Libica and Cirene

Divisions were occupying the approaches to the Pass by nightfall, and began to

move through it on the morning of 14 September. By the afternoon Italian troops

were occupying the 11th Hussars rest and recuperation site at Buq Buq, almost

forty miles from the border. On 15 September the Support Group’s fighting

withdrawal toward Mersa Matruh continued, although the RHA batteries exhausted

their supply of 25-Pounder ammunition in the early afternoon, and the 7th

Armoured Division’s armour was moving west in readiness to begin their

counter-attack on 17 or 18 September.

The slow but seemingly unstoppable Italian advance continued

on 16 September, and by the early evening lead elements of the 1st MVSN

Division entered Sidi Barrani where, at least according to Italian propaganda

broadcasts, non-existent trams were still running. A defensive screen was

pushed out as far as Maktila, fifteen miles to the east, but there the advance

stopped. Over the next few days the remainder of Graziani’s force closed up in

the region of Sidi Barrani, having achieved ‘maximum exploitation’ as planned

sixty miles or so inside Egypt. At first the British assumed that the halt was

temporary, but a close reconnaissance by a Sergeant from the 11th Hussars

revealed the construction of permanent defences, and aerial observation noted

the construction of a surfaced road and water pipeline between Sollum and Sidi

Barrani and the arrival of large amounts of supplies. With that the 7th

Armoured Division’s tank formations were recalled and deployed to cover the

approaches to Mersa Matruh; according to O’Connor they considered their

withdrawal to be ‘rather a disappointment’. The Support Group was also

withdrawn for a well earned rest, and the 11th Hussars took up their watching

brief once again.

On the Italian side Mussolini was soon badgering Graziani to

push on, but the latter was intent on modernising and strengthening his

logistic links to Libya before resuming the offensive, and then only as far as

Mersa Matruh. It was at this point that the Germans made their first, brief

foray into events in North Africa. Following a meeting with his senior land and

air commanders Hitler had cancelled the invasion of Britain, codenamed

Operation Seelöwe (Sealion), on 17 September 1940. As a result the Oberkommando

der Wehrmacht (OKW) began to consider the possibility of deploying an armoured

force to assist their Italian allies in Libya, and with Hitler’s approval

despatched Generalmajor Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma to Libya to investigate the

possibilities. In the meantime the 3 Panzer Division was warned of possible

North African service, and Hitler formally offered Mussolini assistance at

their Brenner Pass meeting on 4 October 1940. Von Thoma’s report was not

encouraging. The situation was judged ‘thoroughly unsatisfactory’, largely due

to the poor road net and resultant logistical difficulties. As the presence of

a German mechanised force would compound the latter severely, von Thoma

therefore counselled against any deployment until Mersa Matruh was in Italian

hands. Hitler accepted the report, 3 Panzer Division was stood down and the

whole idea was placed on the back burner.

In the meantime the British had no intention of allowing

Graziani to make his preparations unmolested, and thus reverted to harassing

the Italians. RAF Blenheims destroyed three Italian bombers on the ground at

Benina airfield near Benghazi on 17 September, and sixty day and night sorties

were carried out against Italian road convoys and forward positions between 16

and 21 September alone. The RAF in Egypt was also receiving more modern

aircraft; by the end of September No. 202 Group had re-equipped No. 33 Squadron

with Hawker Hurricane monoplane fighters and No. 113 Squadron with Blenheim Mk.

IVs, and had operational control of the Vickers Wellington equipped No. 70

Squadron from Middle East Command. However, their effectiveness was offset by

the loss of the forward landing areas in the vicinity of Sidi Barrani. This

reduced the effective range of Nos. 6 and 208 Army Co-Operation Squadron’s

reconnaissance aircraft, a mixture of Lysanders and Hurricanes, by around a

hundred miles and also obliged Blenheims to operate at extreme range to reach

the port of Benghazi, through which much of Graziani’s materiel was passing. It

also removed the possibility of shuttling fighters from Egypt to Malta, and

curtailed air cover for RN vessels operating further west than Sidi Barrani.

This was offset to an extent by the activities of the latter. Fleet Air Arm

aircraft from HMS Illustrious mined the approaches to Benghazi and sank the

destroyer Borea and two cargo ships on 17 September, and nearer the front

destroyers and the gunboats Aphis and Ladybird bombarded targets of opportunity

along the coast from Sollum to Sidi Barrani. The damage was not all one-way,

however. On the night of 17–18 September the cruiser HMS Kent was attacked by

SM.79 torpedo bombers from 240ª Squadriglia Aerosiluranti whilst en route to

shell Bardia; Tenente Carlo Emanuele Buscaglia scored a hit on the cruiser’s

stern which damaged the vessel to the extent it had to return to Britain for

dockyard repair after a temporary fix at Alexandria.

On the ground the 11th Hussars continued to penetrate deep into Italian controlled territory, but the strain of virtually non-stop operations was taking a barely sustainable toll that manifested itself in unreliable and worn-out vehicles and a lengthening list of battle casualties at the hands of the increasingly adept Italians. The Hussars were reinforced in October 1940 with No. 2 Armoured Car Squadron RAF from Palestine, but in the meantime a stopgap response was the formation of small all-arms units equipped with artillery, anti-tank and anti-aircraft weaponry to protect the Hussars as they went about their business. Named ‘Jock Columns’ after the inventor of the concept, Lieutenant-Colonel J.C. ‘Jock’ Campbell RA and drawn largely from the Support Group, these units were tasked to support the 11th Hussars from the end of October. They also engaged in operations on their own, including surveying Italian defences and general harassment including attacking installations and transport in the Italian rear areas. This was all in line with the Support Group’s mission to dominate the seventy miles that separated the main forces between Maktila and Mersa Matruh, to which end the latter’s units also engaged in raiding on their own account. On 23 October 1940, for example, troops from the 2nd Battalion The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders supported by tanks from the 8th Hussars attacked a fortified Italian camp near Maktila. Unfortunately, the Italians were forewarned courtesy of poor security in Cairo, and the attackers were greeted by the Marmarica Division in its entirety. Despite this a platoon of Highlanders penetrated the camp and succeeded in taking prisoners and destroying a number of motor vehicles before escaping in a commandeered truck; unfortunately the truck was shot up by friendly anti-tank fire and the prisoners escaped in the confusion.