“A Long Road Home”: Russian Prisoners in France,

1799-1801

Eman M. Vovsi

There were several reasons – economic, practical and

personal – why Russia participated in the Second Coalition. First, Bonaparte’s

Egyptian expedition 1798-1801 threatened Russia’s exports at the Mediterranean

to market in Europe and elsewhere. Second, Russia had been excluded from the

Second Congress of Rastatt, opening in December 1797 (where Russia, since 1779,

traditionally should have had a seat), which followed in the wake of the Treaty

of Campo-Formio, 17 October 1797, regulating some territorial questions between

France and Austria (as part of the Holy Roman Empire). Finally, the seizure of

Malta by the French at the end of June 1798 – where Tsar Paul I had been the

Protector of the Order of the Knights of the St. John since 1797 – was seen as

an additional expansion of the French hegemony in the Mediterranean. Thus,

Russian armies were sent to Europe – mainly to collaborate in the restoration

of the old pre-Revolutionary order.

According to the treaty with Austria – a major initiator of

the Second Coalition against France’s encroachment in Italy – Russia sent her

forces under overall command of Field Marshal Alexander V. Suvorov to support

the Habsburgs. However, these troops did not come to Italy all at once. The

corps under General of Infantry Diedrich Arend von Rosenberg (originally

21,976) arrived in mid-April 1799, while Lt.-General Maxim Woldemar von

Rehbinder’s corps (10,489) – only in June. Additionally, a corps under

Lt.-General Ivan Hermann von Fersen (17,736) was sent to assist the British in

their invasion of Holland, where the French had established a satellite

Batavian Republic. Finally, Lt.-General Alexander M. Rimsky-Korsakov’s corps

(32,399) was sent to join the Austrian troops under Archduke Karl against the

French army commanded by General André Masséna operating in Switzerland.

While the victories of Field Marshal Suvorov’s in North

Italy over the French Republican armies of Generals Jacques Macdonald and Jean

Victor Moreau are well known, the fate of the Russian soldiers who fell into

captivity during the unsuccessful operations in Switzerland and Holland,

remains little known and therefore merits an in-depth look. The following

article will try to consider the following three basic questions: how many

Russian prisoners were there? what was their experience of captivity, and did

this captivity correspond with the existing norms of international law?

finally, what was the fate of these prisoners in the wake of France’s First

Consul Napoleon Bonaparte’s sudden rapprochement with the Russian Emperor, Paul

I, who agreed to reestablish Franco-Russian diplomatic relations?

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of documents and studies on

this topic. French archival documents dealing specifically with the Russian

prisoners are yet to be discovered. By far the most comprehensive source on the

subject is Istoria voiny Rossii s Franciei v tzarstvovanie Imperatora Pavla I v

1799 [History of Russia’s War against France during the Reign of Emperor Paul I

in 1799], a vast multi-volume study undertaken by the Russian general officer

and historian, Dmitry Milyutin, in 1852-53 and 1857. Utilizing Russia and some

French archival documents, this work offers detailed analysis of military

operations but has only a brief discussion of the fate of the Russian prisoners

taken in Switzerland and Holland. By contrast, General Frédéric Koch’s Mémoires

de Masséna (1849) provides only general observations and imprecise numbers on

operations of General André Masséna in Switzerland in 1799. Equally

disappointing are British sources assembled by Edward Walsh in his The

Expedition to Holland in the Autumn of the Year 1799 (1800), which concentrates

primarily on military operations, the aftermath and following

Anglo-French-Dutch (Batavian) peace negotiations.

However, with the help of an integral approach and

‘microhistory,’ we may glean sufficient information from existing primary and

secondary sources to allow for a reconstruction of the experiences of the

Russian POWs and the subsequent work of the Russian and French governments

towards their release.

In September 1799, according to the new war plan, Field

Marshal Suvorov – fresh from his great victory over the French at Novi in North

Italy (15 August) – advanced through the St. Gothard Pass with some 28,000 men

into Southern Switzerland to relieve the army of Archduke Karl which was

supported by the Russian troops under Lt.-General Rimsky-Korsakov (about 27,000

men). Suvorov ordered Rismky-Korsakov to block French troops under General

Masséna (over 35,000 in close proximity) by attacking them frontally between

Zurich and Glarus – until the main Russian army could properly deploy and take

the French in rear. However, Massena anticipated this maneuver and, on 25

September, he attacked Rimsky-Korsakov in strength and routed his force.

The two-day battle had cost the Russian army nearly 3,000

killed and wounded; 26 guns, 51 artillery wagons and 9 colors were also lost.

Many Russian wounded found a shelter at a nearby monastery

and the farm houses of Einsiedeln (north of modern Schwyz), where monks and

local farmers, hostile to the French soldiers, attended to their needs until

victorious French entered the city and declared all wounded as prisoners of

war.

Meanwhile, some eight hundred kilometers northwest of

Zurich, the Russian corps under Lt.-General Hermann von Fersen supported the

British expeditionary force commanded by the Prince Frederick, Duke of York and

Albany, in a joint invasion of North Holland. After two indecisive battles at

Bergen (19 and 21 September 1799), the Allies went on the offensive, on 6

October 1799, against the Franco-Batavian army, commanded by General Guillaume

Brune, at Castricum. After several unsuccessful assaults, the Allies were

forced to retreat losing over 3,400 men. Disheartened by this setback, the Duke

of York informed General Brune of his readiness to negotiate an armistice. By

the convention signed on 18 October at Alkmaar, the Allied forces returned the

French and Dutch prisoners and evacuated Holland, the Russian contingent being

taken aboard the British vessels to the islands of Jersey and Guernsey.

As of April 1800, there were 11,238 Russian soldiers and

officers on those British islands, all that remained of the 17,736 soldiers and

officers who had originally set off on this Dutch misadventure.

The defeat in Holland, which had a profound effect on

Emperor Paul I, was blamed on the British failure to cooperate, just as the

Russian setbacks in Switzerland was explained by the “treacherous” behavior of

Austria. Field Marshal Suvorov personally wrote to the Austrian Emperor Francis

II requesting the proper exchange of prisoners, including the Russians taken by

the French in Italy and Switzerland. Yet, responding on behalf of his master,

the Austrian Director of Foreign Affairs, Baron Johann Amadeus Franz de Paula

von Thugut, had refused to take part in it. He wrote that the Russian troops in

Switzerland were acting while placed under British financial subsidies and that

therefore Britain should shoulder responsibility for these prisoners. Further

discussions between Russian and Austrian officials proved to be in vain.

On 22 October 1799, Emperor Paul I, incensed by the Austrian

behavior, announced his decision to withdraw from the coalition and ordered his

armies to return to Russia.

But for Russian soldiers and officers who had been captured

in Switzerland and Holland, the road home soon took an unusual turn.

The precise number of the Russian prisoners of war remains

debated. Field Marshal Suvorov’s report stated that “no more than 300 men were

taken prisoners in Italy and about 1,000 in Switzerland” but this document is

most definitely incomplete.

Dictating his reminiscences during his exile on St.-Helena,

Napoleon claimed that there were between 8,000 and 10,000 Russian military

personnel of various ranks taken prisoner during the Italian, Switzerland and

Holland campaigns in summer-autumn 1799.

More reliable are Russian archival documents that list

Russian prisoners being held in France (along with wounded and those who died

in captivity), as of January 1801:

Lt.-General Fabian

Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken; five Major-Generals: Markov, Likoshin, Nechaev,

Garin and Kharlamov (died in prison);

16 staff officers

(4 of which died in prison) and 150 company grade officers (14 died in prison);

6,628 NCOs and

rank-and-file, including 2,459 wounded

Thus, the total number was 6,800 general officers, officers,

NCOs and soldiers.

To this should be added Lt.-General Hermann von Fersen, who

was taken prisoner along with his staff, and some 1,500-2,000 Russian POWs

taken after the two battles of Bergen in September 1799 (total losses killed,

wounded and missing in action estimated at over 4,000). Furthermore, an unknown

number of Russian soldiers and officers were also taken prisoner after the

final Anglo-Russian defeat at the Battle of Castricum, 6 October 1799. At a

local town –now Egmond aan Zee – the Russians left 216 of their wounded who,

most likely, were also declared prisoners by victorious Franco-Batavian

soldiers.

The majority of them was imprisoned on the territory of the

Batavian republic. Therefore, the total number of the Russian prisoners

including wounded could be estimated well over 8,000 men of all ranks.

How did the French treat their prisoners of wars during the

numerous campaigns against the forces of European monarchies? If toward the

last decades of the Old Regime the treatment of prisoners among the major

European countries was more or less civilized – albeit captured officers were

often treated more “nobly” than the rank-and-file – that the outbreak of the

war in April 1792 changed the French attitude towards the first prisoners, such

as Austrians, Prussians, Croatians, etc. Attempting to apply ideals of the

Enlightenment to the harsh reality of war, the French government called for

humane treatment of prisoners. One of the first regulations, issued in early

May 1792, called for gathering prisoners in specially organized localities some

thirty miles from the frontier under “the safeguard of the nation against

violence and rigorous treatment.”

Furthermore, the law of 25 May 1793 established modes of the

prisoner exchanges, excluding from it all émigrés and deserters. Another

document, issued a year later, organized the first special depots, which were

to receive, organize and manage prisoners. Finally, on 3 May 1799, the

Directory issued a decree regarding treatment of enemy prisoners detained in

France: each soldier and NCO was to receive a food ration and a monetary

stipend according to his rank as if he was on the active duty; officers were to

receive payments in the amount equivalent to an inactive French officer’s

payment of corresponding rank. Additionally, this decision called for

establishment of a commission on exchanging prisoners, though it was limited to

the Austrian prisoners only.

Where were the Russian POWs detained? By 1800, all French

field forces – and all French field forces – and their prisoners, taken in

numerous campaigns – were dispersed amongst twenty-six divisions militaires

(military districts) that stretched from Brussels to the Eastern Pyrenees, and

from Paris to Marseilles – and soon, beyond. Since March 1790, the entire

French territory was divided, administratively, into départements (102 by

1800/1801) presided over by civil officials; the military districts, which

usually covered from two to five départements, were commanded by experienced

general officers and members of military administration appointed directly by

the Consular government. They were to act as liaisons between the civil and

military authorities, a task that included observation of territorial

administration and postal services, supervision of conscription and military

command in towns and fortresses, controlling units either stationed in or

marching through the territory; they were also responsible for prisoners

detained in their respective districts in special depots (soldiers) or under

house arrest (officers).

Commanders of military districts corresponded directly with

the Bureau of Prisoners and Foreign Deserters at the War Ministry in Paris,

which oversaw the situation by furnishing necessary funds, selecting depots and

residences, organizing exchanges of POWs or administering the parolees.

Regarding the Russian prisoners detained in France, the

Fourth Military District, led by sixty-six year old General of Division Joseph

Gilot, bore the brunt of responsibility.

With its headquarters in Nancy, his district included

north-eastern départements of Meurthe and Vosges where most of the POWs were

gathered as a result of military campaigns in Italy and Switzerland.

Additionally, Lt.-General Hermann and some of his officers were imprisoned at

the Lille fortress (modern département Nord). Being desperate, he requested

from General Brune’s permission to leave on parole; the French commander, in

turn, forwarded Hermann’s request to First Consul Bonaparte. In response,

Bonaparte’s Minister of War, General Alexander Berthier demanded the release of

general officers Emmanuel de Grouchy, Catherine Dominique Pérignon, Louis de

Colli-Ricci and others, all taken prisoner during Suvorov’s Italian campaign in

1799.

The formal exchange of prisoners began in summer 1800 when

First Consul Bonaparte firmly secured his position after victory at Marengo, 14

June; the French General of Brigade Joseph Julhien, in the service of the

Cisalpine Republic (Milan), was put in charge of this mission, but his

authority was limited to Franco-Austrian exchanges. After the armistice,

Austria was neutralized and the First Consul, feeling the change of political

climate and, no doubt, planning to enforce the Franco-Russian rapprochement –

one of the foundations of his early foreign policy – took this issue further.

Thus, in a letter to the commander of the Fourth Military District, General

Gilot, dated 24 June 1800, the new French War Minister Lazar Carnot, writing on

behalf of the First Consul, outlined the following instructions regarding the

Russian officers in captivity:

“The intention

of the First Consul is that all Russians, who felt victims by the destiny of

our arms, shall be looked after for their unfortunate fate and courage. You

shall personally seek to uphold the French conduct in this regard. The officers

of this nation now are coming under special consideration of the First Consul.

Their bravery, loyalty and delicate situation, which they undertook while in

detention, shall be held in high esteem.

He does not

make distinction [between the French and Russian officers – E.V.] by allowing

them to settle in Paris and hoping that they would find it pleasant; he also

would like to grant an audience to those of them who wish to request so.

You shall

deliver contents of this letter to the Russian officers who are detained within

the borders of your military district and order the issuance of traveling

documents to those who would request it.”

Soon, as an ice-breaker, Lt.-General Osten-Sacken received a

personal letter form the War Minister Carnot on a free lodging in Paris while

on parole, which confirmed First Consul’s good will and a hope that “the French

people would express their trust and good intentions toward the Russian

officer.”

More overtures followed. Since Russian foreign ministers

were forbidden from directly engaging with Republican France’s representatives,

French Foreign Minister Charles Maurice Talleyrand used his alternative

diplomatic channels in Hamburg to deliver, on 18 July 1800, an official letter

to Russian Vice-Chancellor Nikita Panin. This letter, besides placing blame on

both Britain and Austria for the previous conflicts, served as a chivalrous

gesture. First Consul Bonaparte offered, without any compensation, to return

all Russian prisoners held in France. At the same time, the Russian mission in

Berlin received a proposal from the Batavian Republic in which its government

expressed willingness to release Russian prisoners captured during the Holland

expedition.

This offer of prisoner exchanges marked not only a formal

end of the War of the Second Coalition but, as far as Russia was concerned, it

led to a veritable diplomatic revolution. Tsar Paul I, who felt embittered

towards his erstwhile allies, was won over by this sudden show of empathy from

his former enemy. Starting in August 1800, Berlin was chosen as a place for

negotiations between French and Russian representatives whereas the Prussian

Foreign Minister Christian August Heinrich Curt von Haugwitz acted as a general

mediator. During its sessions, the French minister plenipotentiary in Berlin,

General of Division Pierre Riel Beurnonville confirmed that since both Austria

and Britan refused to exchange the Russian POWs, First Consul Bonaparte was

willing “while paying respect to the brave Russian troops,” to release them

without any conditions or obligations from the Russian Tsar.

At first, Bonaparte’s original offer to release the Russian

POWs was met with a rather cool response from the Russian tsar who replied that

he could only accept it on the understanding that these troops would swear not

to fight against France. He wanted to avoid any imputation of an unconditional

gift.

However, this response marked a good start for the

negotiations; the Tsar soon communicated, through his minister in Berlin, Baron

Burghard-Alexis Krüdner, that he was grateful for the French offer and that he

would send Göran Magnus Sprengtporten, a Russian general of mixed

Finnish-Swedish origins who was well known for his pro-French sympathies.

Sprengtporten’s mission to Paris was not limited to just negotiating the return

of the Russian prisoners; Sprengtporten was, in fact, instructed to try to

improve Franco-Russian relations, as well. The Russian Tsar’s state of mind is

well illustrated in the instructions which were given to Sprengtporten:

“… [T]he

[Russian] Emperor participated in the coalition with the aim of giving

tranquility to the whole of Europe. He withdrew when he saw the powers were

aiming at aggrandizements which his loyalty and disinterestedness could not

allow, and as the two states of France and of Russia are not in position, owing

to the distance [separating them], to do each other any harm, they could by

uniting and maintaining harmonious relations between themselves, hinder the

other powers from adversely affecting their interests through their envy or

desire to aggrandize and dominate.”

Besides technicalities regarding the Russian POWs, General

Sprengtporten was also told to to form two infantry regiments out of the

prisoners of war; it was generally understood that in the event that Malta fell

to the English, the island would be occupied by Russian, English and Neapolitan

troops. But when British Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson took Malta on 4 September

1800, he announced that he intended to hold the island until a peace conference

could determine its future. A senior Russian officer was dispatched to take

over the newly formed regiments who, freshly armed and accounted, were to be

used to garrison Malta once the island had been recovered from the British.

This, however, did not happen, and Malta remained the apple

of discord which eventually led to the rupture of the Peace of Amiens and the

formation of the Third Coalition.

Meanwhile, Tsar Paul issued new instructions to General

Sprengtporten, who was told to lead former Russian POWs back to Russia; all

generals, staff and company-grade officers were to be reassigned to their

respective units while preserving their previous ranks and seniority. While in

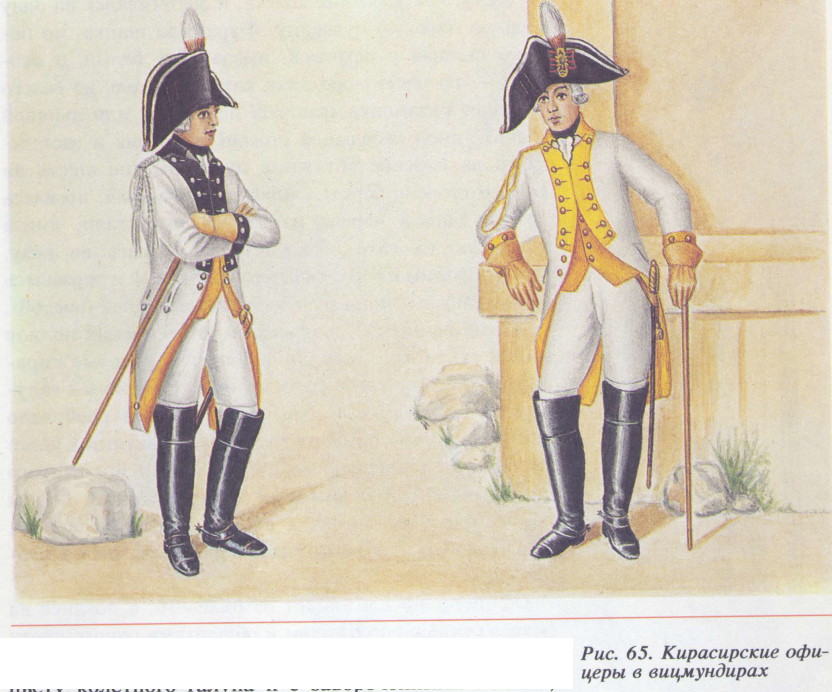

exile on St. Helena, Napoleon reminisced that all Russian officers received

their swords back; Russian prisoners were reunited at Aix-la-Chapelle/Aachen

where they supposedly received new uniforms, equipment and armament made at

local manufactures.

However, until today, no precise information has been

retrieved from the French archives that such new uniforms (subject to Tsar Paul

I regulation issued in mid-December 1796) along with new elements of equipment

and flags had been, in fact, made. Furthermore, there is no information

regarding the exact departure of the Russian POWs from France. General

Sprengtporten’s diary, which he submitted to the Topographical Department of

the War Ministry, stops after the 6 March 1801 entry when the column was

probably already on the march to Russia. Some of these soldiers and officers

would eventually return to France – either as new prisoners of the 1805-07

campaigns or as victors, such as general officers Osten-Sacken and Markov, in

1814. They certainly remembered the humane treatment by the French inhabitants

and officials during their days of misfortune and tried to pass these good

memories on to their soldiers.