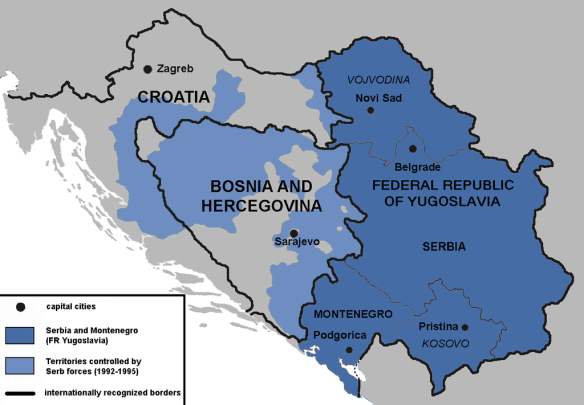

Serbian-held territories of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars. The War Crimes Tribunal accused Slobodan Milošević of “attempting to create a Greater Serbia“‘, a Serbian state encompassing the Serb-populated areas of Croatia and Bosnia, and achieved by forcibly removing non-Serbs from large geographical areas through the commission of criminal activity.

The Perpetrators

In every society people exist who voluntarily commit crimes.

Whether due to narcissistic personality disorders or sadistic dispositions,

these people experience a feeling of exuberance and liberation in their

actions. The snipers of Sarajevo, for example, enjoyed putting victims in their

crosshairs and having an unbridled power over life and death, as one of them

stated in an interview. Among the volunteers in the special operations units

were many who were filled with hatred toward an envisioned enemy, enjoyed

killing, or simply craved the business of war. The warlords attracted social

outsiders, petty criminals, hooligans, and weekend fighters who saw the war as

an adventure or a way to earn extra income.

However, the widespread expulsion on the scale experienced

in Bosnia was only possible because thousands of “ordinary men,” and very few

women, participated in these crimes alongside those who were predisposed to

violence. The International Criminal Tribune for the former Yugoslavia

estimates that 15,000 to 20,000 people participated in planning, administering

and executing “ethnic cleansing,” including members of the political

leadership, the bureaucracy, the police, and the military, who acted on their

own or carried out the instructions of their superiors. Many described later

that they experienced the war as a matter of defense in which killing was a

necessary evil. A sense of duty, an ideal of masculinity, and group pressure

interacted here. “There was no choice,” testified the Serb commander Dragan

Obrenović. “You could be either a soldier or a traitor. … We didn’t even notice

how we were drawn into the vortex of interethnic hatred.” Others were driven by

delusion, a sense of duty, opportunism, fear, sadism, or greed. Exhaustion,

stress, and alcohol led to emotional deadening and lowered inhibitions. The

police chief of Bosanski Šamac, Stevan Todorović, simply lost his nerve in the

face of the daily artillery shelling, the mountain of corpses, and the plight

of refugees. He was scared, panicky, and became an alcoholic. In this

condition, he paid little attention to the butchery carried out by his

subordinates. Many defended their actions on the reasoning that they were

simply carrying out their superior’s orders, similar to the excuses of German

executioners from the Second World War. Dražan Erdemović, a 23-year-old

executioner in Srebrenica, emphasized that he had fled from the executions at

the first available opportunity. Allegedly he did not kill willingly.

Amid all this, individuals still had leeway and opportunity

to make their own choices. Grozdana Ćećez, a Serb woman who was raped every

evening by her Muslim guards at the Čelebići camp, tried to ward off the

attacks by humiliating her abusers with the question: “I could be your mother …

don’t you have a mother?” The effect varied. Only one of the men was

embarrassed, apologized, and left without having done what he had come for.

Others, however, were not halted by her words, including one of her husband’s

former work colleagues and one of her son’s classmates.

Perpetrators found it easier to justify their own actions if

they could resort to symbolic forms of legitimation. The president of the Serb

Republic in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Biljana Plavšić, expressed remorse and referred

to her obsession over time with experiences and memories from the Second World

War. Radovan Karadžić reached into the prop box of folklore to proclaim himself

the descendant of the linguistic scholar Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and had

himself filmed in a bizarre pose wearing historical costume. Hajduks, the Robin

Hoods of the Balkans during the Ottoman era, were depicted as the role models

for the warlords. Whoever took part in the battles were perpetuating the

historical fight and carrying on the tradition of heroic deeds that had been celebrated

in oral history for generations.

The Media and the Escalation of Violence

The International Tribunal for Yugoslavia came to the

conclusion that the media was guilty of contributing significantly to the

brutalization of the war. Radio, television, and the printed press created

enemy images and stereotypes, spread rumors and untruths, provoked fear, hate,

and revenge, and broke down moral barriers. They resorted to well-tested

propaganda strategies to give the war the necessary psychological underpinning,

especially by portraying everything as black or white, by demonizing the enemy,

by ignoring, exaggerating, and falsifying information, by drawing parallels

between current occurrences and historic events and myths, by using hateful

language and constantly repeating the same messages. The authors of a study on

media communication noted correctly that the Yugoslav war was “the mere

continuation of the evening news by military means.”

Since the motto “no pictures, no news” prevailed in the

media age, the warring parties hired professional public relations agencies

abroad to promote their cause. Alone in the United States, they signed at least

157 contracts with partners between 1991 and 2002, a figure that most certainly

represents just the tip of the iceberg. Among the jobs to be done, for example,

was to improve the image of Slovenia and Croatia as Western European countries

or to equate the Serbs with Nazis. Thanks to satellite technology and digital

recording, editing, and transmission capabilities, international news

channels—especially CNN, BBC, and later Al Jazeera—brought images of the war

directly from the crisis regions to the rest of the world, thereby mobilizing a

global civil society calling for humanitarian and military intervention.

Hate-filled tirades appeared in the media on all sides,

making it soon hard to distinguish between true and false. In the Serbian

evening news, an alarmed public learned that Muslim extremists had supposedly

fed Serb children to the lions in the Sarajevo zoo. More dangerous than such

horror myths were the many unverifiable, one-sided, or falsified news stories

about events that sounded plausible, such as the report that Bosnian troops

were shelling their own civilian population in Sarajevo in order to place the

blame on the Serbs. German politicians were also tricked into believing a bogus

report or two, including one in which Serb doctors were said to be implanting

dog fetuses into Bosniak women. Such stories not only perpetuated repulsive

images of the enemy, they also appealed to forms of media voyeurism.

The war allowed aggression to be acted out openly and

provided a framework in which violent acts were suddenly wanted, encouraged,

and socially sanctioned. Under exceptional conditions, people can certainly be

tempted into committing deeds that they never would do under peaceful

circumstances. This makes it almost impossible to maintain friendly neighborly

relations in wartime. Once war has erupted, it becomes the source for a vicious

cycle of never-ending violence. It alters ideas, emotions, aims, behavior, and

identities of people from the ground up. People who are otherwise respectable

citizens may carry out personal vendettas under the guise of higher national

interests and thus attribute a type of private meaning to the war, and this may

even prompt acquaintances to go after one another.

Insecurity and anxiety are the most important means by which

to transform ethnic distance and latent nationalism into open antagonism. The

1993 British documentary We Are All Neighbors shows how uncertainty and fear,

rumors and media disinformation, followed by the first violent incidents and

finally the outbreak of war, turned peaceful coexistence into distrust, then

rejection, and eventually hate. In a village not far from Kiseljak in central

Bosnia, life seemed to be rather normal in 1993. As long as the artillery fire

was only to be heard faintly in the distance, Croats and Muslims met for coffee

as usual. No one believed that anything could change the good neighborly

relations. But the more the war interfered with daily life and the closer the

front approached the village, the more uneasy people began to feel. By the time

the first refugees arrived, people were talking about “us” and “them.” Visits

with one another became less frequent; some no longer greeted the others. Out

of doubt grew distrust, out of insecurity developed fear, and out of that,

betrayal. When Croat troops were about to launch an attack on the village and

therefore warned the local Croats, not one gathered up enough courage to inform

their Muslim neighbors. All Muslims could do once the assault started was to

tear out of town head over heels under a shower of grenades.

Similar examples of crumbling solidarity could be observed

everywhere as people became fearful of losing their homes or their lives. In

mid-1991, the Croat Witness E reported that, shortly before the assault on

Vukovar, his Serb friends left town. Why, he asked them. “They would shrug

their shoulders and they would say, ‘We believe you will see it soon too.’”

Witness DD, whose husband and two sons were murdered in the massacres in

Srebrenica, described the relationship to her Serb acquaintances: “We were

friends, in fact. We went to have coffee at each other’s houses. And if we were

working on something, we would help one another. We would help them, and they

would help us.” She later saw one of these neighbors standing among the

soldiers who took away her 14-year-old son, who was never seen again. At that

moment she remembered that many Serb women and children had left the area a few

days before the attack. “Then someone asked, ‘Where are you going? What’s

happening?’ … Their answer was very vague. ‘Some fools could come along and do

who knows what.’ … And we were wondering. Until then, they didn’t do anything

wrong. They didn’t hurt us and, of course, we didn’t hurt them either.”

Containment Policy

While public opinion in the West favored military

intervention in light of the horrific images from Bosnia that flicked across

people’s television screens every evening, political leaders remained reticent.

Die for Sarajevo? Politicians and military experts knew that it would not be

enough to simply make threatening gestures, but they feared the risks of

deploying ground troops. Nor was there any hope that an intervention could

offer political solutions since the warring parties had already rejected one

peace plan after another.

Because the war continued to escalate, the credibility and

reputation of the international community in dealing with Yugoslavia suffered.

Miscalculations and delayed reactions as well as conflicting national interests

and evaluations prevented the West from presenting a united front and made it

look thoroughly helpless, disoriented, and devoid of any overall concept on how

to cope with the situation. An army of special envoys, diplomats, and military

experts scurried around just trying to catch up with the tumultuous events,

hundreds of ceasefires were broken, and the heads of state of the world’s greatest

powers exposed themselves to public ridicule by arrogant provincial politicians

from the Balkans. Not only did the international community lack the political

will to form a united approach, it also possessed no effective instruments of

conflict management.

For all these reasons, the international community limited

itself to developing a strategy of humanitarian relief and containment. It

imposed an arms embargo and commissioned the United Nations in Sarajevo with

the distribution of food and medicine. Serbia and Montenegro, which had united

as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, were punished in May 1992 with

comprehensive economic and diplomatic sanctions. In February 1993, the UN

Security Council established the International Criminal Court for the Former

Yugoslavia to prosecute the worst war crimes.

In light of the relatively weak response from the West, the

Bosnian government received support from the Islamic world. Hundreds of

millions of U.S. dollars are thought to have been spent between 1992 and 1995

on illegal weapon sales. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Malaysia, and Indonesia were

particularly prominent sponsors. Radical, violence-prone groups from abroad

also arrived in the embattled region, including up to five thousand Iranian,

Afghani, and Saudi mujahideen fighters who joined the Bosniak armed forces.

Although conflicts between Saudi Arabia and Iran, between the Sunnis and

Shiites, stood in the way of a unified Islamic policy, pan-Islamic solidarity

was strengthened. This encouraged the re-Islamization of Bosnian Muslims, who

felt abandoned by the West.

Brutal “ethnic cleansing” continued to force thousands of

people to flee to the cities, where unsustainable conditions had prevailed for

months. Therefore, the UN Security Council declared Srebrenica, Sarajevo,

Tuzla, Žepa, Goražde, and Bihać “safe areas” in April and May 1993. Lightly

armed Blue Helmet peacekeeping forces were to provide humanitarian aid under

the protection of possible NATO air strikes. The concept of the safe areas

revealed serious flaws from day one, starting with the fact that peacekeepers

were being sent into a region in which there was no peace to keep. The rules of

their deployment referred to consent of the conflicting parties, impartiality,

and nonuse of force except in self-defense. The Blue Helmets therefore did not

have either the mandate or equipment and arms necessary for active battle.

“Knowing that any other course of action would jeopardize the lives of the

troops, we tried to create—or imagine—an environment in which the tenets of

peacekeeping … could be upheld,” stated UN secretary-general Kofi Annan later.

The Security Council passed more than 200 resolutions to stitch together a

complex and contradictory mandate, the boundaries of which were

incomprehensible to all. Where did this mandate start, where did it end? Ultimately,

the tragedy was that the term “safe area” duped the population into believing

these areas offered a measure of protection that actually never existed.

Furthermore, there was an extreme disparity between the UN’s aims and its

resources: instead of the 34,000 soldiers demanded by UN headquarters to man

the six designated safe areas, the UN member states only sent 7,500 soldiers to

serve.

Meanwhile, the possibility of “humanitarian intervention”

was being debated throughout the West. These debates between advocates and

opponents of such intervention were particularly controversial in Germany,

where the central question was whether Germany should and could participate in

military operations abroad in the future, although these were expressly

prohibited by the constitution. Because the German air force had been

participating in the international airlift to Sarajevo since July 1992, members

of Germany’s Liberal and Social Democratic parties turned to the Constitutional

Court in April 1993. The judges ruled on 12 July 1994 that Germany could take

part in peacekeeping missions without having to first amend the constitution,

as long as parliament approved the mission by simple majority. Step by step,

the self-imposed limitation on military involvement that had prevailed in

Germany since 1945 gave way to a greater acceptance of the idea to deploy

German troops abroad and to assume a new foreign policy role in world politics.

Srebrenica

On the morning of 11 July 1995, Bosnian-Serb army and police

units stormed the safe area of Srebrenica, which had been under artillery fire

for days. Although the president of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, had

ordered the removal of the Muslim population from the enclaves of Srebrenica

and Žepa back on 8 March, the attack caught the 150 Dutch UN troops deployed

there completely by surprise. During the torturous July days that followed, as

many as 8,200 men and boys were systematically executed by Serb forces, making

the Srebrenica massacres the first legally recognized genocide on European soil

since 1945. In a tragic way, this incident symbolized the belated, helpless,

and fully inadequate response of the West.

From the standpoint of the Bosnian Serbs, there were many

reasons to attack the city. They viewed eastern Bosnia as ancient Serbian

territory, the Drina River as an “internal river” and not a “border,” as

General Mladić expressed it. “The main obstacle today is Srebrenica with which

the Germans and Americans, who defend it, want to fix Serbia’s border at the

Drina,” he said in addressing his soldiers. “It is your task to prevent this.”

In the summer of 1995, Mladić’s troops controlled all of eastern Bosnia with

the exception of a few enclaves, while the Bosnian army only launched attacks

periodically against the regions surrounding what were actually demilitarized

safe areas. Bosniak troops had grown increasingly strong since 1994, had

retaken regions, and were preparing to break the siege of Sarajevo in the

summer of 1995. In this context, the Bosnian military pulled soldiers out of

Srebrenica, a clear indication that they did not intend to make a serious

effort to defend the enclave. Furthermore, the Serbs could count on

encountering no resistance from the UN peacekeeping troops. That spring a

precedent had been set in Croatia in which the Croatian army had overrun the UN

safe area in western Slavonia and driven out the Serb population living there.

Last but not least, contempt and revenge against the balija, a derogatory term

for Muslims, played a role after Muslim militias had caused a bloodbath in the

villages of Glogova and Kravica on the Orthodox Christmas Eve of 1993. “Kad,

tad”—sooner or later, Serbs vowed, there would be revenge.

A dangerous concoction of strategic scheming, nationalist

incitement, and outright vengefulness was brewing as Mladić’s men waited for an

opportunity for the ultimate reckoning with the Muslims. In the preceding

months, thousands had flown to the safe area from the large territories under

Serb control. Instead of 9,000 people, there were now 30,000 people in the

city—another reason why the UN military experts believed that Srebrenica could

not be taken by force. General Mladić assessed the situation differently and

assumed that he could force the city to surrender without a major battle by

placing it under siege. However, contrary to expectations, Muslim soldiers,

along with a good number of the male population, decided to break out of town

during the night of 11 July. This made the Serbs hopping mad. It was then, at

the latest, that Mladić must have given the order to massacre as many men and

boys as they could find. Following the assault on the city, his troops captured

all those seeking protection on the grounds of the UN compound in Potočari or

hiding in the surrounding woods. Thousands were taken away in buses, packed

into empty school buildings or warehouses, and then slaughtered like livestock

or systematically executed.

The 17-year-old Witness O, who was able to escape, severely

injured, after a mass shooting on the morning of 15 July 1995, recounted the

events of that night: “The situation was chaotic. We were all tied up. … the

firing started, and then they would call out people in groups of five. … And

when it was my turn … we were told to find a place for us, … when we were on

the right-hand side of the truck, I saw rows of killed people. It looked like

they had been lined up one row after the other. … And when we reached the spot,

somebody said, ‘Lie down.’ And when we started to fall down to the front, they

were behind our backs, the shooting started. … I felt pain in the right side of

my chest. … I was waiting for another bullet to come and hit me and I was

waiting to die. … I don’t know how long it took. They kept bringing people up.

… Once they had finished, somebody said that all the dead should be inspected …

and if they find a warm body, they should fire one more bullet into their

head.” Miraculously, Witness O was overlooked, so that he was later able to

crawl away on all fours into the forest.

Both the UN and the government of the Netherlands promised

to investigate and report their findings on the greatest mass murder of postwar

European history to a shocked world. Their reports placed responsibility on

many shoulders: the UN Security Council, for limiting its involvement to

containment and choosing a peacekeeping mission that was not implementable and

based on an ill-conceived concept of safe areas; the UN member states, for

sending too few, poorly trained, and insufficiently equipped Blue Helmets into

a highly dangerous operation; the imprudent UN commanders in Srebrenica who did

not have serious reconnaissance equipment at their disposal, for evaluating the

situation quite falsely up to the bitter end and for not concerning themselves

with the fate of those taken prisoner by the Serbs after the town fell; the

headquarters of the UN peacekeeping forces in Zagreb, for turning down requests

by the UN troops on site for NATO air power; and the defense minister of the

Netherlands, for supporting that decision because he feared reprisals against

fifty-five of his soldiers who served as Blue Helmets and who were being held

hostage by the Serbs. Yet, with all that said, incidents of mass murder on this

scale far exceeded what most people could have imagined.

The Dayton Peace Accord

NATO had been bombing Serb positions on a limited scale

since the brutal mortar attack on the Markale market in Sarajevo on 6 February

1994, in which at least 68 people were killed and 197 injured. But the

Srebrenica massacre became a clarion call to action for the West, and the

alliance started a campaign of massive bombardment. With the help of foreign

arms shipments and American military advisers, the Croatian and Bosniak armed

forces became more professionally run, improved their military clout, and could

seriously challenge the previously superior Bosnian Serb army. The myth of Serb

invincibility was definitely shattered when the Croatian army overran the UN

safe area in western Slavonia in May 1995 and finally conquered the so-called

Republic of Serb Krajina in its Operation oluja (Storm) in August 1995, thereby

driving away 150,000 to 200,000 Serbs. In cars, buses, and horse-drawn wagons,

tens of thousands of men, women, and children fled head over heels, with barely

any time to gather together the bare necessities. Once the political leadership

also bolted, the statelet collapsed altogether. The Serbs only managed to hold

onto an area in eastern Slavonia that was later reincorporated peacefully into

Croatia. As far as it was concerned, Zagreb had thus solved the “Serb question”

permanently. Very few of the displaced Serbs returned to their homes when the

war ended.

All of these factors led to a military standoff in mid-1995.

Bosnian Serbs and Croat-Muslim troops each controlled about half of the

territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina. That fall, U.S. special envoy Richard

Holbrooke presented an agreement that he intended to bulldoze through. For

three weeks, the presidents and the delegations from Bosnia-Herzegovina,

Croatia, and Serbia were housed in a lockdown situation at Wright-Patterson Air

Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, until they came to an agreement on 21 November

1995. The peace accord was formally signed in Paris a month later on 14

December.

The Dayton Accord squared the circle by keeping

Bosnia-Herzegovina as a unified state with its prewar borders (Muslim position)

and by dividing it into two quite independent yet constituent entities (Serb

position). The Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was ruled by Croats and

Muslims, received 51 percent of the territory and thus a symbolic majority. A

complicated system of cantons was meant to fulfill the Croat demand for

autonomy (but never did). The other entity continued to be the Serb Republic

(Republika Srpska), which received 49 percent of the territory. Very few

competencies were delegated to the central government in Sarajevo, namely

foreign policy, issues of citizenship, and monetary policy. The so-called

entities governed themselves practically autonomously and were permitted their

own currency, police force, and army. The agreement guaranteed that all

refugees and displaced persons could return and demanded the prosecution of war

criminals. To implement the accord, the international community installed a

High Representative with quasi-dictatorial powers and sent a 60,000-strong

peacekeeping force under NATO (and later EU) command.

The initial euphoria over the end of the war soon subsided,

and the general mood sobered. Society had changed to such a degree that

peaceful coexistence of the different nationalities seemed impossible. Roughly

100,000 people had lost their lives, and more than two million had been driven

from their homes. The Dayton Accord created a highly complicated and barely

functional state that was weakened by a general unwillingness to cooperate,

political radicalism, and serious economic problems. Last but not least, the

new state suffered from the fact that a major part of the population did not

identify with it.