THE STRATEGIC LEVEL

The strategic level Prussian war aims and strategy changed

in the course of the three Silesian Wars from territorial expansion in the

first two wars to the survival of Prussia as a great power with the

Hohenzollern dynasty at its head in the Seven Years’ War.

Frederick had to wage war simultaneously against three other

major powers and a number of smaller powers. Since Prussia enjoyed no

protection either by a fortress belt like France or by strategic depth like

Austria and Russia, the multiple onslaught could only be stopped by the

Prussian army in battle. Therefore, attempting to fight decisive battles, and

forcing one enemy after the other to withdraw from the war, answered best

Frederick’s interests.

The high stakes in this war, the imperative to raise and

maintain an army equal to the military threat and the scarcity of Prussian

manpower and resources forced Frederick to mobilize his country for war to the

utmost degree. In addition, Frederick’s battle-seeking strategy made a high

degree of mobilization even more urgent, since frequent combats would tear gaps

into the Prussian ranks and call for numerous replacements. Furthermore,

efficient administration permitted not only exhaustive but also rapid

mobilization, which helped Frederick to occupy key strategic territory such as

Saxony at the outset of hostilities.

Frederick was able to mobilize the necessary quantity of men

and material because Prussia’s social and economic structures were designed to

sustain Prussian military power. Economic policy ensured that the army’s

material needs were fulfilled and as much revenue as possible filled the war

chest. In this context, Frederick made considerable strides towards

industrialization. The army, in turn, helped the economy since soldiers were a

source of cheap labour. Agriculture received military assistance as the army

gave artillery horses to farmers in times of peace. This served both army and

farmers: the army did not need to feed the horse in peacetime, and the farmer

had a strong farm animal at his service. Another example of interlocking

economic and military arrangements was the grain magazines: when grain prices

were low, magazines would fill their stocks. When grain prices were high, thus

making life difficult for recipients of fixed wages such as soldiers and

labourers, magazines sold stocks and pushed prices down again.

Social policy also played its part. Townspeople were exempt

from service but they had to provide billets and forage and pay taxes for the

war effort. The peasantry not only paid taxes and rendered ancillary services,

many of them also had to serve in the army. This service obligation was due to

the canton system, which required each regimental district to apply selective

conscription in order to fill the regiments if not enough mercenaries could be

recruited. In order to prevent economic damage and consequent loss of revenue,

only the least productive elements of that part of the population liable for

canton duty were called up and even they would serve for only two months per year.

Care was taken to recruit as many mercenaries as possible to leave most

Prussian subjects free to work and pay taxes. Consequently, no more than a half

to two-thirds of troops consisted of cantonists. The army’s control over them

was absolute. Officers granted or refused the right to marry, intervened in

legacy matters in order to ensure that the strongest son, even if firstborn,

would become a soldier, demanded labour service on roads and fortifications,

driver services for train and artillery and excessive contributions in cash and

kind. The recruitment demands on that part of the population liable for canton

duty were high. In 1762, the Prussian army mustered 260,000 men, seven per cent

of the population, most of them cantonists.

In addition to the tax-paying townspeople and the serving

and tax-paying peasantry, the nobility was also a major source of Prussian

military strength. The relationship between king and nobility was symbiotic.

The power of the king rested on the loyalty of his nobles, who were obliged to

serve in his army. Supervision was close, each officer being subjected to

institutionalized scrutiny of his behaviour in service as well as private life.

The strong grip of the king on his noblemen became obvious in the winter of

1741- 1742 when Frederick had driven his officers so hard that scores of them

asked for dismissal, only to see their demands turned down. In return for

faithful service in danger and hardship, the noble officer corps enjoyed the

highest social standing, symbolized by the king himself wearing the uniform and

leading his army as the first among equals. In order to bolster this status,

the nobility enjoyed a near-monopoly on the military profession, and was

granted an immense amount of power and control over their serfs. When an

officer became invalid or old, he served in the administration, seconded by

former non-commissioned officers in subordinate administrative positions.

Having military men in the bureaucracy not only permeated this body with the

military code of loyalty and honour but may also have reduced friction between

army and administration, which was useful in the context of mobilization.

Not only this administrative arrangement, but also

Frederick’s role as a soldier-king proved important for the war effort.

Frederick was his own minister of finance, economics and foreign affairs as

well as commander-in-chief. The integration of policies and military strategy,

due to Frederick’ s close control over every aspect of affairs of state and

war, probably contributed to Prussia being the only continental power that was

not just able to cater to all the army’s needs in terms of weapons, uniforms,

equipment, supplies and cash, but also finished the Seven Years’ War with

well-filled coffers. The close interrelationship between economy, social

structure and military organization made Prussia a military state able to

mobilize manpower, money and material to a degree astonishing for such a small

country.

Yet, for all these efforts, mobilization was not complete.

Mercantilist principles called for a strict distinction between those who had

to fight and those who had to produce revenue, demanding that as many men as

possible should work rather than fight. Consequently, only a part of the

able-bodied male population was called up. Mercantilism discouraged recourse to

the full mobilization of Prussian males, and the feudal structure of society

prevented the large-scale admission of commoners into the officer corps.

Commoners had career prospects only in the artillery, the engineer corps, the

hussars and the free corps, though, due to rising officer casualties, they were

increasingly to be found in all arms towards the end of the war. This

restriction of admission to the officer corps barred the military talents of many

commoners from being employed in the service of the Prussian state.

Consequently, Prussia’s human resources were only partly exploited.

Limitations in the mobilization of Prussian manpower, such

as the failure to introduce universal military service and the meritocratic

principle, could not be overcome without radically changing Prussia’s social

structure and the attitudes on which this structure was based. The same kind of

limitations applied to agricultural reform. The evolution of agriculture from feudal

to capitalist modes of organization and production was deliberately delayed in

order to preserve the economic and social bases of Prussia’s noble officer

corps.

Apart from the mobilization of manpower and material, modest

efforts towards spiritual mobilization were made. Frederick and Maria Theresa

launched a war of propaganda against each other. Frederick tried to impress the

justness of his cause on the public, to the point of producing faked Austrian

diplomatic correspondence in order to justify his pre-emptive strike against

Saxony in 1756. Austrian writers regaled their mostly Catholic audience with

comparisons between the Protestant Frederick and Lucifer.

In the century to follow, the state would appeal to the

force of nationalism in order to rouse the population for war. Not so in

Frederician Prussia. The Prussian subject had to obey the laws and pay taxes.

The king had no interest in rousing the feelings of the population and

supplying it with arms. He was, nonetheless, prepared to take recourse to

state-organized guerrilla warfare and the mobilization of peasant militias if

this seemed unavoidable. Most instances of armed resistance by the Prussian

peasantry, however, were prompted by the spontaneous desire to defend personal

property and the safety of the family rather than by royal order or nationalist

sentiment.

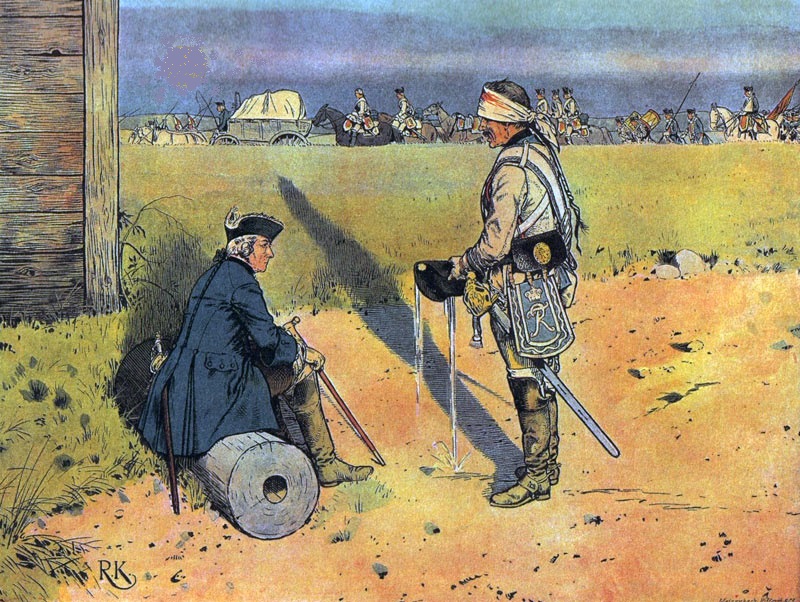

Rather than kindling the fervour of the population, it was

more imperative to motivate soldiers to countenance the risks of their

profession. High rates of desertion in the Prussian army, as in other armies of

the period, suggest that soldiers were not always willing to accept these

risks. The prevalence of this problem is highlighted by Frederick’s

instructions to his generals which begin with a long list of measures to prevent

desertion. Such measures had a deleterious effect on military effectiveness.

Generals had to keep marches short in order to prevent straggling; this reduced

strategic speed. Generals had to avoid night marches since they offered

soldiers opportunities to disappear into the darkness; this reduced strategic

flexibility. Generals had their troops sleeping in tents rather than in the

open in order to keep them under close supervision; the consequence being that

tents swelled the baggage train. Hussars were more busy circling the army like

shepherd dogs than carrying out reconnaissance. Patrols were kept close to the

main body to prevent them from vanishing. Generals had to forbid soldiers to

search for food, fearing that they might not return. This fear, apart from the

general poverty of local supplies, prevented the army from living off the

country. Generals were forced to take utmost care of their communications since

a hungry army could simply melt away like the Prussian army in Bohemia in 1744.

Generals were reluctant to have their troops fight in open order since this

offered the individual soldier opportunities to skulk. In spite of this

preoccupation with preventing desertion, the willingness of soldiers to fight was

often astonishing and gave lie to the popular notion that Frederician soldiers

only fought because they feared their officers more than the enemy.

That fear of punishment alone cannot explain this bravery

becomes obvious with a look at battalions of Saxons, press-ganged into the

Prussian army, which went over to the enemy in scores in spite of a severe

penal code. There are enough other examples which show that troops, and even

officers, would run if they were determined not to fight. Positive motivation

can be credited to esprit de corps, the pride of the soldier in his profession,

Frederick’ s charisma, paternalism and cohesion due to cantonists of the same

village serving together.

Prospects for plunder, cash rewards and promotion also

played a role. Nationalism had not yet become a potent force, though it was not

uncommon for ethnic antagonisms to increase troops’ aggressiveness. The

much-quoted use of the stick in Frederick’s army need not have had a very

deleterious impact on morale. On the one hand, the use of violence as a

pedagogical cure-all was commonplace as teachers hit their pupils, parents hit

their children and craftsmen hit their journeymen. In this period, offenders as

young as 9 years were publicly executed for minor offences. On the other hand,

corporal punishment may even have increased morale. Since only the stupid,

vicious or lazy soldiers were beaten, their more attentive or intelligent

comrades who avoided the stick may have felt honoured by this distinction. The

importance of the Lutheran faith and its concept of duty should also not be

overlooked as there were several instances where regimental chaplains rallied

broken battalions. Only the consistently high spirit can explain why the

Prussian army’s morale did not crack during this long and bloody conflict, why

desertion sometimes decreased prior to battle, and why the army did not simply

dissolve after the crushing defeats of Kolin and Kunersdorf.

When mobilization was complete, the army took to the field.

Campaign objectives varied from year to year. The aim of some campaigns, such

as those of 1744 and 1758, was to put pressure on the Austrian court by

attempting to advance on Vienna. The objective of the 1756 campaign was to take

Saxony out of the reckoning as an opponent and to exploit its resources, which

were essential for the Prussian war effort. The aim of most Prussian campaigns

during the Seven Years’ War was to expel armies which had intruded

Prussian-controlled territory or were bound to do so. This strategic situation

called for the pursuit of decisive battle. Limitations inherent to warfare in

this period, however, made it difficult for Frederick to achieve such a

decisive battle.