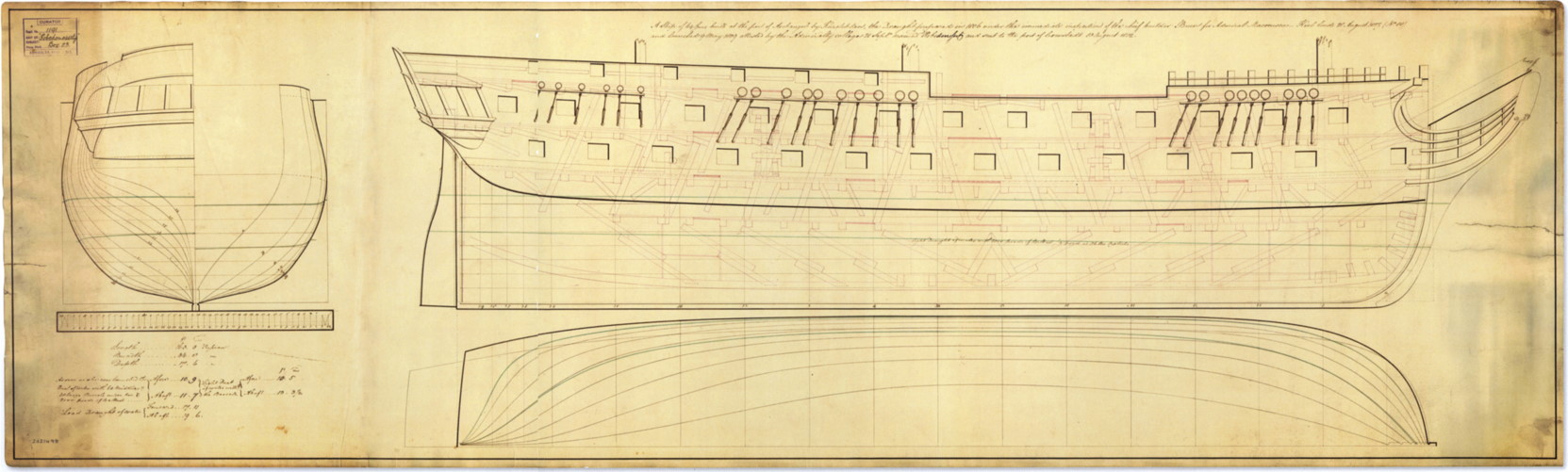

A SHIP OF 64 GUNS BUILT AT THE PORT OF ARCHANGEL BY

KUROTCHKIN, THE DRAUGHT PREPARED IN 1806 UNDER THE IMMEDIATE INSPECTION OF THE

CHIEF BUILDER BRUN FOR ADMIRAL MACOEUSCA. KEEL LAID 28 AUGUST 1807, (NO 88) AND

LAUNCHED 1809 ATTESTED BY THE ADMIRALTY COLLEGE 21 SEPTR NAMED POBEDONOSSETS

AND SENT TO THE PORT OF CRONSTADT 10 AUGUST 1812.

The provenance of this draught is conundrum: on the one hand

it is decidedly English in style, calligraphy and even ink colours, but on the

other, it is annotated with information that could only have come from Russian

sources – the launching draughts of water are quoted in Russian units and a

note describes the lower green line as ‘Light Draught of water with 2000 poods

of Ballast (a pood is 36 lbs English)’. The ship was in British waters with

Admiral Crown’s squadron in 1812–1814 and may have had the lines taken off

then, or this may have been copied from a Russian original and annotated in

English. A noteworthy feature of the structure is the system of substantial

diagonal braces in the hull; this is not the full trussed frame as developed by

Seppings, but a less effective fore-runner, and when considered alongside the

numerous top-riders may suggest the ship was lightly framed. This reinforcing

may have been required by the ship’s heavy armament of twenty-six short 36pdrs,

twenty-eight short 24pdrs and fourteen guns on the upperworks (a mix of long

8pdrs and 24pdr carronades). The ‘lightweight’ guns were supposedly inspired by

Swedish models, but there were many other experiments around this time with

weapons mid-way between carronades and traditional long guns, like the

proposals of Sadler, Gover and Congreve in Britain.

[SKETCH OF THE FRIGATE VENERA, 48 GUNS]

This is actually a Russian draught whose provenance is

unknown, although it may be associated with Samuel Bentham, who was

well-connected in Russia, having served there before the war – indeed, Bentham

was in Russia from 1805 to 1807 trying to arrange for the construction of

British ships on the White Sea. Built at St Petersburg and launched in 1808,

Venera was a big ship, measuring 162ft 6in between perpendiculars, with a 42ft

beam, and a calculation on the draught puts her displacement at 1693 tons

(although the conventional figure for burthen would be less). The absence of

barricading on the forecastle looks backwards, but the hull form, with its

rising floors and wall sides, is more reminiscent of the 1820s and ’30s than

the first decade of the century. The armament was originally thirty 24pdrs and

eighteen 6pdrs, but in 1810 she was converted to a flush two-decker and two

24pdrs and all the 6pdrs were replaced by twenty-eight 24pdr carronades, giving

the ship a one-calibre weapons-fit and anticipating the ‘double-banked frigate’

of the post-war decades.

The ‘edinorog’ was a uniquely Russian artillery piece,

designed to fire either solid shot or an explosive round. This is a 1780 Model

gun of ‘1/2-pood’ calibre – roughly equivalent to a British 24pdr when firing

round shot (the explosive shell weighed less at about 20 pounds). On line of

battle ships, it was usual to mount one per deck on each broadside, alongside

the solid-shot guns of the nearest calibre. This very limited employment

suggest that their advantages were more theoretical than real – they are known

to have suffered from massive recoil, and the dangers of handling explosives

aboard wooden ships deterred other navies from pursuing similar experiments, so

their use in the Russian service may well have been limited.

The Russian navy was no better understood in the West during

the eighteenth century than its Soviet successor was in the twentieth.

Distance, the Cyrillic alphabet, and a Tsarist penchant for secrecy conspired

to keep information to a minimum, yet the Russian navy in 1790 was a major

force: at about 142,000 tons the Baltic fleet alone was larger than all Dutch

naval forces combined, while a further 40,000 tons in the Black Sea was

approximately the same size as the Swedish navy. Depending on the precise date

chosen, together they constituted the world’s third or fourth largest navy. In

1798 the Baltic fleet’s official establishment comprised nine 100-gun ships,

twenty-seven 74s, nine 66s, nine 44s, one 40 and nine 32s; for the Black Sea in

1797 it was three 100s, nine 74s, three 66s, six 50s and four 3 6s. These

figures, however, were aspirations – the first 100-guns ships for Black Sea

were not launched until 1801–2 – but they do indicate the magnitude of the

Russian navy.

It was also a successful force, having won significant

victories over Sweden in 1788–90 and the Ottoman Empire in 1787–92. Although

Peter the Great is regarded as the father of Russian seapower, it was Catherine

II (1762–96) who was responsible for the development of a European-standard battlefleet

that was employed with so much strategic impact. This period also saw much

technical improvement, with considerable effort expended keeping up with

British, and to a lesser extent French, naval technology. A decline in numbers

set in during the reign of Alexander I after 1801 and thereafter the navy did

not recover its relative position until the mid-1820s.

For much of the struggle with Revolutionary and Napoleonic

France, Russia was Britain’s ally. Elements of the Baltic fleet co-operated

with Duncan in the blockade of Dutch ports, and made a major contribution of

fifteen sail of the line to the Helder expedition in 1799. Catherine had

experienced some success in attracting British officers into the Russian fleet,

but its general state of efficiency did not impress the Royal Navy nor the

officials of the Dockyards who had to refit and maintain the Russian ships.

They were regarded as poorly built of inferior timber, and a list of the Baltic

Fleet in 1805 gives an average age of ten years for thirty-two ships of the

line.

In 1798 the Russians deployed some of the Black Sea fleet to

the Mediterranean, where a squadron under Vice-Admiral Ushakov occupied the

Ionian Islands and after a long siege captured Corfu. The force was withdrawn

in 1800, but a more significant development was the formation of a

Mediterranean fleet by the dispatch of a squadron from Cronstadt, a long voyage

by Russian standards, to join elements from the Black Sea at Corfu. Commanded

by Vice-Admiral Seniavin, who had served six years in the Royal Navy, this

fleet of ten sail of the line was active against both the French in the

Adriatic and later the Turks, where it successfully blockaded the Dardanelles

and won a crushing victory over the Ottoman fleet at Lemnos on 19 June 1807.

The events leading up to the Tilsit agreement between

Napoleon and the Tsar rapidly turned the Russian fleet from ally via neutral to

enemy in a matter of weeks. Having given up Corfu to the French, the Russians

were forced to leave the Mediterranean, but in the face of a hostile British

fleet took shelter in the Tagus, where they were promptly blockaded. Eventually,

in September 1808 Seniavin agreed to the internment of his fleet in Britain and

the repatriation of its crews. Eventually, eight two-deckers and two frigates

were turned over. While laid up they gradually deteriorated and only two ships

returned to Russia in 1813.

In the 1790s the Baltic fleet could boast eight 100-gun

three-deckers of the Chesma class (supposedly inspired by, or even copied from,

Slade’s Victory), but they were poorly constructed and by 1801 none was fit for

active service. A huge 130-gun ship, the Blagodat, was launched in 1800, again

modelled on a famous western prototype, in this case the Spanish Santisíma

Trinidad. Armament was usually 3 6pdrs on the lower deck with 18s and 8s

respectively on the higher gundecks, and 6pdrs on the upperworks. Contrasting

with this investment in concentrated firepower, the majority of the Russian

battlefleet was made up of small two-deckers in the 66-gun class, which were

built in large numbers down to 1797. Even with 24pdr main batteries, they

proved perfectly adequate against their usual opponent, the Swedes (which was

equally true for the Black Sea fleet and the Turks). The 74-gun ship came late

to the Russian navy, the first pair being launched in 1772, and although they

carried 30pdrs on the lower deck they were still relatively small ships,

comparing in size with the British ‘Common Class’. By 1800 the Baltic fleet’s

two-deckers comprised twenty 74s and twenty-four 66s.

A unique feature of Russian naval weaponry was the edinorog,

a large calibre lighweight gun capable of firing a wide range of ammunition

including explosive shells. Generally known by the French term licorne

(‘unicorn’), they usually filled a pair of ports on the two lower gun-decks of

battleships (and two pairs on 100-gun ships), but they were regarded as a

dangerous and doubtful asset by other navies. Eventually the Russian navy came

to agree and the gun establishment of 1805 abolished them. It also introduced a

homogeneous armament for all two-deckers of new lightweight-pattern 36pdrs and

24s, and added the first carronades (24pdrs) to the upperworks.

The Black Sea fleet was a recent venture, established in

1770, but growing from seven ships of the line in 1790 to thirteen in 1800.

Although an equivalent of a First Rate was not laid down until 1799, the

average size of its ships tended to be greater than those of the Baltic fleet,

where navigational conditions and the restricted dimensions of the opposing

Swedish warships constrained growth. The Black Sea squadron, in fact,

introduced both the two-decker 80 and the 24pdr-armed big frigate to Russian

service – in the latter case, what were termed ‘battle frigates’ stood in the

battle line when required. The first was launched in 1785 and thus pre-dated

the better-known 24pdr frigates of either the French or US navies. However,

even this was later than the Swedish Bellona class designed by af Chapman,

although these usually cruised with 18pdrs and were designed to ship light

24pdrs only when war threatened so that they could reinforce the outnumbered

Swedish battlefleet. As counters to these vessels, Russia’s Baltic fleet built

five 24pdr frigates in the 1790s, and more after 1801, thus becoming one of the

first major sponsors of the type – and as potential oceanic commerce-raiders,

as much a concern to the Royal Navy after 1815 as US big frigates. This was in

marked contrast to Russia’s earlier conservatism in cruiser design, being slow

to adopt the frigate-form (in either 12pdr or 18pdr calibres), and persevering

with small two-deckers until the late 1780s. Not having the same requirement as

the Atlantic navies for long-distance, all-weather cruisers, the advantages of

a high battery freeboard combined with a low topside height were less

compelling. Nevertheless, the Baltic fleet built nine 18pdr frigates before

1800, when they were eclipsed in construction programmes by the 24pdr type.

Although the Russian navy list included sloops, brigs and

many of the small craft familiar from other navies, these did not exist in very

large numbers. Russia had little ocean-going commerce to protect, and fleet

scouting and support duties usually fell to small frigate-like vessels.

However, in both the Baltic and the Black Sea it invested heavily in specialist

types for inshore warfare, usually craft that could be rowed – including

traditional ‘Mediterranean’ galleys – and amphibious warfare vessels. These

were not as ingenious as the special types devised by AF Chapman for the

Swedish archipelago fleet, but were equally effective in their chosen

environment. A significant contributor to this requirement was a force of large

sea-going bomb vessels, making both Russian main fleets the only force outside

the Royal Navy to employ such vessels on a regular basis. Four survived in the

Baltic into the 1790s and two more were built in 1808; in the Black Sea fleet

two were in service up to 1795, and another was built in 1806.