The foundation of the Parthian legions did, however, lead to

changes in the expeditionary forces, particularly their overall command

structure. The legio II Parthica was designed to accompany the emperor on

campaign, a role it performed during Septimius Severus’ two Parthian wars and

his British expedition. The question of whether the legion came under the

direct command of the praefectus praetorio is a vexed one. In Cassius Dio’s

Roman History the character Maecenas advises Octavian that the praetorian

prefect should control all the forces stationed in Italy, a statement that

could be taken refer to the situation in Dio’s own lifetime. As an official

imperial comes during Severus’ Parthian campaigns, the prefect Fulvius

Plautianus certainly joined the emperor in the east, but he is not mentioned in

any specifically military capacity, in contrast with the abundant evidence for

Severus’ senatorial generals leading troops in battle. It seems likely,

therefore, that the authority of the praetorian prefect over the legio II

Parthica evolved gradually. During Caracalla’s campaign against the Parthians

his expeditionary force was composed of the legio II Parthica, the cohortes

praetoriae, and the equites singulares Augusti, as well as vexillations of

legions based on the German, Danubian and Syrian frontiers, totalling some

80-90,000 soldiers. This is what scholars call a `field army’, a modern term of

convenience used to describe a large force composed of vexillations from a

range of legions and auxiliary forces, which accompanied emperors or their

leading generals on campaigns. Apart from the legio II Parthica, the only other

legion that may have participated in Caracalla’s campaign as a complete unit

was the legio II Adiutrix of Pannonia. This meant that the legio II Parthica

was effectively the central core of the force and – although no ancient source

explicitly attests this – the logical commander of the field army would be the

praetorian prefect. Both of Caracalla’s prefects, M. Opellius Macrinus and M.

Oclatinius Adventus, are known to have accompanied him to the east. This necessitated

the appointment of a substitute prefect in Rome to handle the judicial

responsibilities of the position.

The legio II Parthica later formed the core of the forces

marshalled by Severus Alexander and Gordian III for their eastern campaigns

against the revived Persian empire. Indeed, it is during Gordian III’s reign

that the connection between the legion and the praetorian prefect is shown

clearly for the first time. Both the emperor’s praetorian prefects, C. Furius

Sabinius Aquila Timesitheus and C. Iulius Priscus, formed part of the retinue

that left Rome for the Persian front in AD 242. In the same year, Valerius

Valens, praefectus vigilum, is attested in Rome `acting in place of the

praetorian prefect’ (vice praef(ecti) praet(orio) agentis). In this capacity he

oversaw the discharge of the veteran soldiers of the legio II Parthica. These

men had originally enlisted in AD 216, and had been left behind in Rome rather

than journeying to the east. The prefects on campaign with their emperor became

enormously powerful individuals: C. Iulius Philippus, who succeeded

Timesitheus, was able to arrange the downfall of Gordian III in the east, and

returned to Rome as emperor. Successianus, an equestrian commander on the Black

Sea in the 250s, was summoned by Valerian to serve as his praetorian prefect in

the east, where he commanded the field army against the Persians. The

composition of Valerian’s army is strikingly demonstrated by the account of the

Roman forces in the account of the Persian king Shapur, known as the Res Gestae

divi Saporis. This includes the detail that the praetorian prefect was captured

by the Persians in AD 260 alongside the emperor and members of the senate. The

employment of the legio II Parthica as a permanent core of the emperor’s own

field army enhanced and consolidated the position of the praetorian prefect as

a senior military commander in addition to the senatorial generals.

The rise of the field armies attached to the emperor and the

praetorian prefect sometimes offered new opportunities to soldiers of other

ranks. In the previous section we observed the marked correspondence between

soldiers who served in the praetorian guard, the equites singulares, and the

legio II Parthica, and those who obtained advancement into the militiae

equestres or the promotion of their sons to equestrian rank. Proximity to the

emperor and his senior staff on campaign evidently had its advantages. The same

phenomenon can be observed in the careers of prefects of the legio II Parthica,

which, since it accompanied Caracalla to the east, was intimately bound up with

the political machinations of the years AD 217-18. In this period the empire

passed from Caracalla to his prefect Macrinus and then to the boy emperor

Elagabalus, with the crucial battles all happening in Syria. The commanders of

the legio II Parthica included Aelius Triccianus, who had begun his career as a

rank-and-file soldier in Pannonia and ostiarius (`door-keeper’) to the

governor. Other ostiarii are attested as being promoted to centurion, so it is

likely that Triccianus himself became a centurion and primus pilus, a career

path attested for comparable equestrian legionary prefects. This was a

spectacular career, but not unprecedented or improper. The same can be said for

P. Valerius Comazon, who served as a soldier in Thrace early in his career,

before rising to become praefectus of the legio II Parthica. Again, there is

nothing truly exceptional in and of itself about soldiers who ascended to the

Rome tribunates or camp prefecture via the primipilate. But the command of the

legio II Parthica offered connections to the imperial court, and the favour of

Macrinus and Elagabalus, respectively, enabled Aelius Triccianus and Valerius

Comazon to enter the ranks of the senate. Their promotion earned the ire of the

senatorial historian Cassius Dio, who disliked the progression of soldiers into

the amplissimus ordo. Dio did not resent the advancement of equestrians per se,

but the elevation of soldiers who were able to enter the equestrian order and

then into the curia. Triccianus and Comazon were quite different from M.

Valerius Maximianus, who originated from the curial classes of Pannonia. Such

opportunities would only become more common as emperors spent more time on

campaign with their field armies.

In addition to the creation of the Parthian legions and the

growing importance of the field army, the first half of the third century AD

witnessed equites appointed to ad hoc procuratorial military commands. We have

already noted this phenomenon in the wars of Marcus Aurelius, when M. Valerius

Maximianus and L. Iulius Vehilius Gallus Iulianus commanded army detachments

with the rank of a procurator, as a way of compensating for the lack of any

defined military pathway for equestrians after the militiae. In the reign of

Severus Alexander, P. Sallustius Sempronius Victor was granted the ius gladii

with a special commission to clear the sea of pirates, a command that was

probably associated with his existing procuratorship in Bithynia and Pontus.

This creation of new military commands within the procuratorial hierarchy can

also be seen vividly in the case of Ae[l]ius Fir[mus]. Following a series of

financial procuratorships in Pontus and Bithynia and Hispania Citerior

(high-ranking posts in and of themselves), Fir[mus] was placed in charge of

vexillations of the praetorian fleet, detachments of a legio I (possibly

Parthica or Adiutrix), and another group of vexillations, in the Parthian War

of Gordian III. In this capacity he ranked as an army commander and procurator

at the ducenarian level, without actually holding a standing military post

(such as fleet prefect, praesidial procurator or praetorian prefect). The

adaptability of the equestrian careers to meet the new demands is demonstrated

by the case of a certain Ulpius [-].227After series of administrative

procuratorial positions, Ulpius was praepositus of the legio VII Gemina. Since

this legion was normally stationed in northern Spain, Ulpius probably commanded

vexillations of the legion in a war conducted in the reign of Philip. He then

returned to the usual procuratorial cursus, serving as sub- praefectus annonae

in Rome.

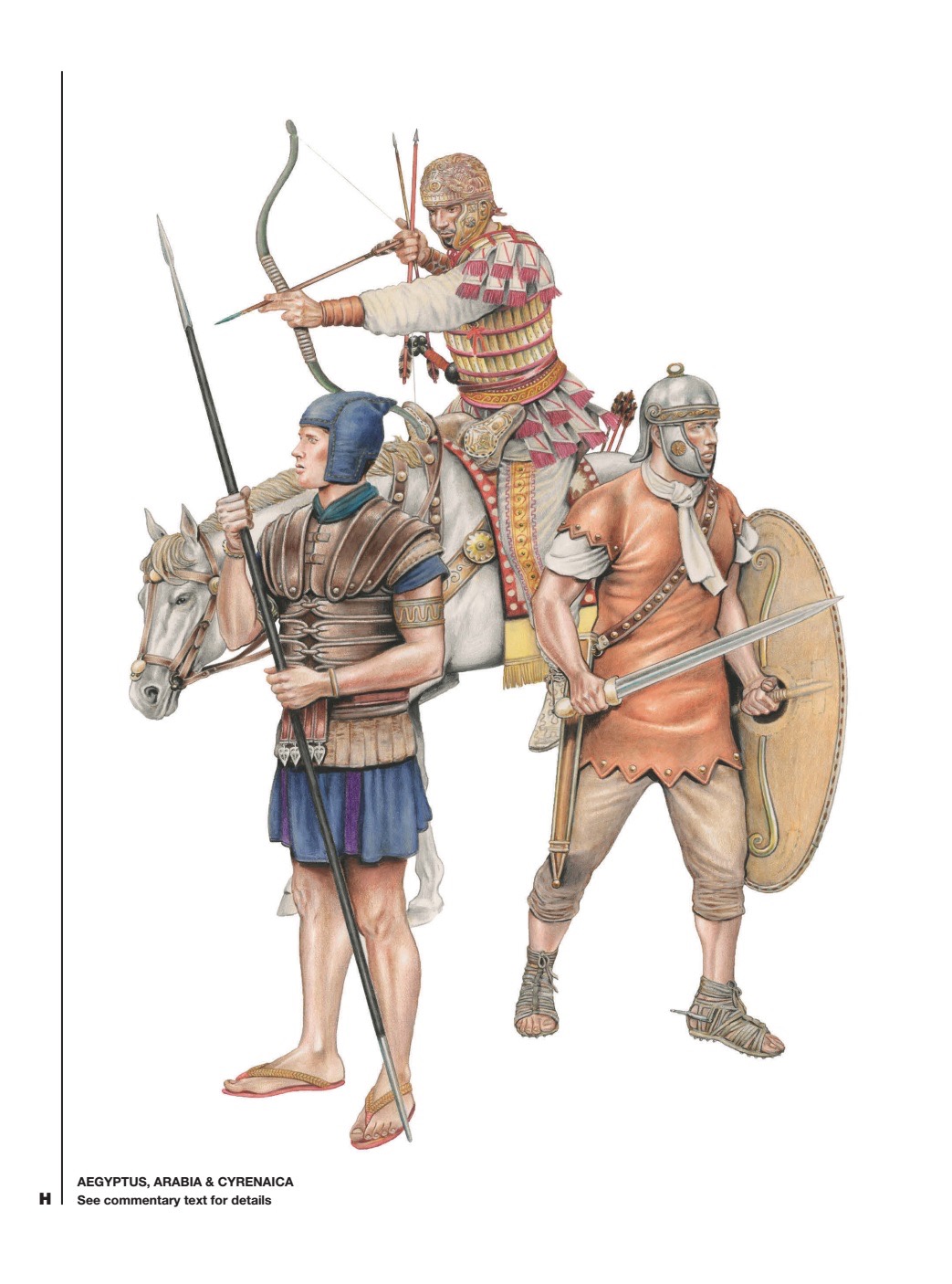

Some equestrians were given special appointments as dux with responsibility for a specific province or series of provinces. This can be observed in Egypt, where generals with the title of dux or commander appear in the 230s-240s. The archaic Greek word σρατηλάτης is rarely used in the imperial period before the third century AD; the only exception is inscribed account of the career of the Trajanic senator and general C. Iulius Quadratus Bassus at Ephesus. But it makes a reappearance in the third century AD to describe senior equestrian military commanders. The first Egyptian example is M. Aurelius Zeno Ianuarius, who replaced the prefect in some, or probably all, of his functions in AD 231. His military responsibilities should be connected with the beginning of Severus Alexander’s Persian War. The second dux/σρατηλάτης mis attested ten years later, in AD 241/2, which is precisely when war broke out between Romans and Persians again under Gordian III. This time, the dux was Cn. Domitius Philippus, the praefectus vigilum, who appears to have been sent directly to Egypt while retaining his post as commander of the vigiles. In both cases the new military command was an ad hoc addition to their usual equestrian cursus. The final example occurs in the 250s, when M. Cornelius Octavianus, vir perfectissimus, is attested as `general across Africa, Numidia and Mauretania’ (duci per Africam Numidiam Mauretaniamque), with a commission to campaign against the Bavares. This substantial command was in succession to his appointment as governor of Mauretania Caesariensis. Octavianus then departed to become prefect of the fleet at Misenum, working his way to a senior post in the equestrian procuratorial cursus. All these cases show the essential adaptability of the imperial system, which allowed third-century emperors to appoint equestrians to senior military commands when it suited them. This may have been because an equestrian was the person the emperor trusted most in the circumstances; for example, Cn. Domitius Philippus, as praefectus vigilum, was one of the most senior officials in the empire. This represents the same pragmatic approach we saw in the appointment of equestrians as acting governors. On a practical level, it did not matter whether an army commander was an eques Romanus or a senator, because the military tasks that he was capable of performing, and was entrusted with by the emperor, were essentially the same. The new ad hoc army commands gave members of the equestris nobilitas further opportunities to serve the state domi militiaeque alongside the senatorial service elite.

At the same time, it is necessary to point out that these

changes did not lead to senators being ousted from military commands prior to

the reign of Gallienus. Rich epigraphic evidence, combined with the testimony

of Dio and Herodian, preserves a long list of Septimius Severus’ senatorial

generals. P. Cornelius Anullinus, L. Fabius Cilo, L. Marius Maximus, Ti.

Claudius Candidus and L. Virius Lupus commanded Severus’ troops as duces or

praepositi in one, or both, of his civil wars against Pescennius Niger and

Clodius Albinus. Candidus also participated in the emperor’s Parthian

campaigns, alongside Ti. Claudius Claudianus, T. Sextius Lateranus, Claudius

Gallus, Iulius Laetus and a certain Probus. These senators were rewarded with a

range of honours, from consulships and governorships to wealth and property

(the sole exception was Laetus, who was executed for being too popular with the

troops). In the face of such overwhelming testimony, it proves difficult to

marshal support for the still-popular scholarly argument that Severus

prioritised equestrian officers over senators. Equestrian commanders continued

to participate in campaigns as subordinates to the senatorial generals, as we

see in the case of L. Valerius Valerianus, who commanded the cavalry at the

Battle of Issus under the authority of the consular legate, P. Cornelius

Anullinus.

The same pattern can be found in Severus Alexander’s Persian

War of AD 231-3. Herodian’s History, our major historical account of this

conflict, is notoriously deficient in prosopographical detail. Yet senators are

attested in inscriptions, as in the case of the senior consular comes, T.

Clodius Aurelius Saturninus, who accompanied Alexander to the east. The senator

L. Rutilius Pudens Crispinus, praetorian governor of Syria Phoenice and legate

of the legio III Gallica, also served as a commander of vexillations during

this conflict. But we only know about Crispinus’ command from an inscription

from Palmyra, which recounts the assistance rendered by the local dignitary

Iulius Aurelius Zenobius to Alexander, Crispinus and the Roman forces. The

inscribed account of Crispinus’ career from Rome merely states that he was

legatus Augusti pro praetore of Syria Phoenice. It is probable that senatorial

governors, such as D. Simonius Proculus Iulianus, consular legate of Syria

Coele, continued to play important roles in eastern conflicts under Gordian

III. Indeed, the evidence for equestrian procurators acting vice praesidis in

Syria Coele, discussed above, suggests that the procurator assumed judicial responsibilities

while the consular governor was preoccupied with warfare. This indicates that

senatorial governors continued to play a major part in military campaigns, even

if it was not specifically noted in inscriptions recording their cursus.

This argument is supported by the literary sources that show

senators assuming military commands through to the middle decades of the third

century AD. We can observe this in particular in the Danubian and Balkan

region, which was a near-continuous conflict zone. Tullius Menophilus fought

against the Goths as legatus Augusti pro praetore of Moesia Inferior in the

reign of Gordian III. During the incursion of the Goths under Cniva in AD

250/1, the Moesian governor C. Vibius Trebonianus Gallus successfully defended

the town of Nova. In AD 253 M. Aemilius Aemilianus, governor of one of the

Moesian provinces, pursued the fight against the Goths, before being acclaimed

emperor. Senators also continued to receive special commands, as in the case of

C. Messius Quintus Decius Valerinus and P. Licinius Valerianus, both future

emperors, who were placed in charge of expeditionary forces by the emperors

Philip and Aemilius Aemilianus, respectively. In Numidia, the governor C.

Macrinius Decianus conducted a major campaign against several barbarian tribes

in the middle of the 250s. In fact, if we examine the backgrounds of the

generals who claimed the purple up to and including the reign of Gallienus, the

majority of them were actually senators, a fact obscured by the common use of

the term `soldier emperor’ for rulers of this period. Decius, one of the few

known senators from Pannonia, successfully allied himself with an Etruscan

senatorial family when he married the eminently suitable Herennia Cupressenia

Etruscilla. His successor, Trebonianus Gallus, was of remarkably similar

background to Etruscilla, coming from Perusia in central Italy. The emperor

Valerian likewise had close links with the Italian senatorial aristocracy,

marrying into the family of the Egnatii. Some of the more ephemeral emperors

deserve notice too, such as Ti. Claudius Marinus Pacatianus, the descendant of

a Severan senatorial governor, who rebelled in the reign of Philip. P. Cassius

Regalianus, who was probably consular legate of Pannonia Superior when he began

an insurrection against Gallienus in 260, was himself descended from a Severan

suffect consul. These men were not soldiers promoted from the ranks, but

senatorial generals who used their positions to make a play for the imperial

purple.

The Roman military hierarchy in the first half of the third

century AD was therefore characterised by a mixture of continuity and change.

The creation of the legio II Parthica, and the necessity for the emperor and

his praetorian prefects to campaign on a regular basis, meant that emperor was

in close contact with members of the expeditionary forces. Officers in the

field army could receive imperial favour and embark on spectacular careers,

like Aelius Triccianus or Valerius Comazon, or even Iulius Philippus, the

praetorian prefect who snatched the purple from Gordian III while in the east.

It is no coincidence that many of the soldiers’ sons attested with equestrian

rank belonged to the praetorian guard, the equites singulares and the legio II

Parthica. At the same time, the imperial state tried to create senior army

roles for promising equites in a manner analogous to senatorial legates by

instituting ad hoc procuratorial commands (as seen in the case of Valerius

Maximianus and Vehilius Gallus Iulianus). This gave members of the equestris

nobilitas, the equestrian aristocracy of service, access to army officer

commands beyond the militiae equestres. It should be noted that for the most

part these men were not lowborn ingénues from the ranks, but members of the

municipal aristocracy who served the res publica in a comparable manner to

senators, as their predecessors had before them. It is also imperative to point

out the endurance of tradition within the high command. Senatorial legates and

generals still commanded armies in the emperor’s foreign wars on the Rhine,

Danube and Euphrates frontiers. Their military authority continued to make them

viable and desirable candidates for the purple in the first half of the third

century AD. There was as yet no attempt to undermine the positions of

senatorial tribunes or legionary legates. It was the dramatic developments in

the 250s-260s that provided the catalyst to set the empire on a radically

different path.