The first recorded combat use of the Maxim was in the

British colony of Sierra Leone on 21 November 1888. A small punitive expedition

under General Sir Francis de Winton was sent out to deal with a tribe that had

been raiding various settlements. The British troops took with them a caliber

.45 Maxim gun that de Winton had purchased. Using the Maxim, the British troops

rapidly routed their opponents at the fortress of Robari. A contemporary report

in London’s Daily Telegraph noted that the “tremendous volley” of

fire caused the tribesmen to flee for their lives; it further stated,

“Such was the consternation created by the rapid and accurate shooting of

the gun that the chief war town was evacuated, as well as the other villages of

the same nature, and the chiefs surrendered, and are now in prison.”

The British Army adopted the Maxim in 1889, originally in

caliber .45 but later in caliber .303. The Maxim changed the equation in

colonial battles, giving the Europeans a decisive advantage. One of the first

uses of the new weapon after its official adoption by the British Army was by

colonial forces in the Matabele War of 1893-1894 in the Northern Transvaal of

South Africa. A detachment of 50 British infantrymen with four Maxims defended

them- selves against 5,000 native warriors who charged them five times over 90

minutes. Each time, the charges were stopped about 100 paces in front of the

English lines by the devastating Maxims. It was recorded that 5,000 dead lay in

front of the English position after the battle.

Maxims were also used effectively by British colonial troops

on the Afghan frontier during the Chitral campaign of 1895 against the mountain

tribesmen of the Hindu Kush. Elsewhere, the Maxim continued to make a name for

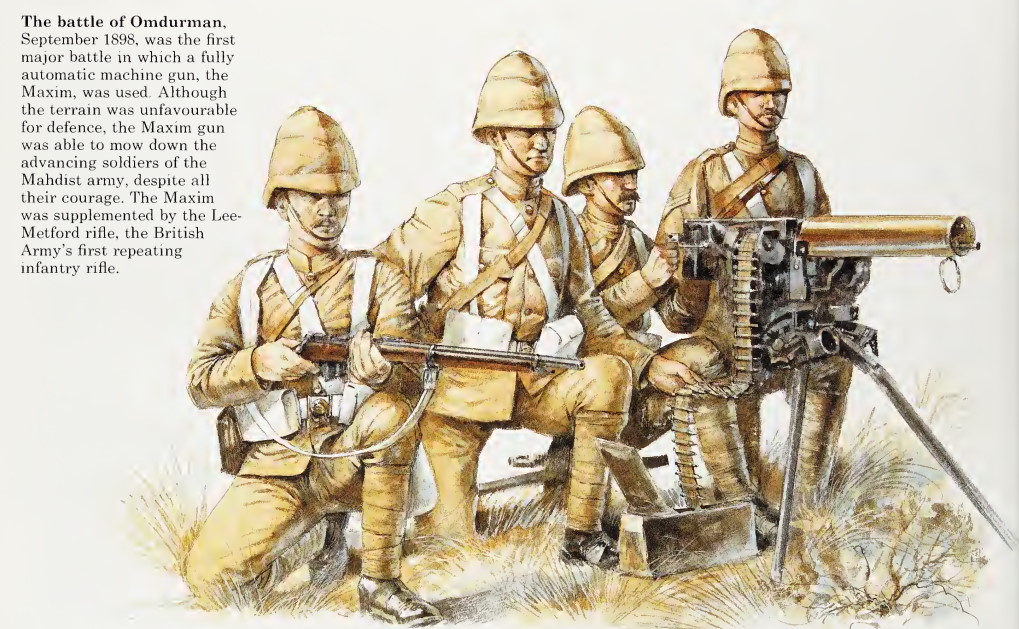

itself. In 1898, at the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan, the disciples of the

Mahdi, the fabled Dervishes, repeatedly hurled themselves against British

lines, only to be re- pulsed each time by six Maxim guns firing 600 shots per

minute. “It was not a battle, but an execution,” reported G. W.

Steevens. “The bodies were not in heaps … but … [were] spread evenly

over acres and acres.” Another British observer proclaimed, “To the

Maxim primarily belongs the victory which stamped out Dervish rule in the

Sudan.” It is doubtful that Lord Kitchener and his troops could have

prevailed without the Maxim guns.

Still, the weapon was not without its limitations. The

Maxims were not well-suited for mobile warfare in mountains and jungles, where

the enemy could fight dispersed or become invisible. There were also

difficulties in effectively employing the weapons; pushed too far forward, they

might become isolated and their crews overwhelmed. Also, the Maxim, at this

point in its development, was not free of mechanical problems and had a

tendency to jam at the most inopportune times. Nevertheless, the Maxim in the

hands of British troops proved successful in colonial campaigns on the Indian

frontier, in the Sudan, and in Africa. Still, progress in selling the army at

home in Britain on the utility of the machine gun was very slow. This suggested

that military authorities were not yet convinced of its applicability to more

traditional concepts of warfare due to the limitations of the weapons. The

British War Office exhibited little interest, regarding it as useful in warfare

against colonials but having little utility on the civilized European

battlefield. Such an attitude would inhibit the consideration of new tactics

and doctrines to make the most efficient use of these deadly weapons.

IMPROVEMENTS IN DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE

Maxim went back to his workshop and dedicated himself to

improving the weapon and making it lighter, simpler, and more reliable. Within

three months, he completed a major overhaul of the original design. The weapon,

reduced to just over 40 pounds in weight, still used recoil as the driving

force, but Maxim replaced the flywheel crank with a toggle-type lock that

greatly simplified the extraction, feeding, and firing cycle. This improved

design was so effective that it was to serve largely unchanged in some armies

until World War II.

In another major innovation, Maxim improved the feeding mechanism

by devising a cloth belt stitched into pockets, each pocket carrying a

cartridge. The movement of the block extracted a cartridge from the belt, fed

it down in front of the chamber, and moved the belt one cartridge at a time. As

long as the gunner pressed the trigger and the belt was long enough, the Maxim

gun could fire indefinitely, deriving its energy anew from every shot it fired.

Even though Maxim made the modifications requested by the

British Army, something that resulted in a much better weapon, he still met

resistance. In European armies, most officers came from the landowning classes;

left behind by the Industrial Revolution, they still thought of war in terms of

the bayonet and the cavalry charge. They clung to their belief in the centrality

of human power and the decisiveness of personal courage and individual

endeavor; after all, one did not pin a medal on any gun. Additionally, they

thought that the machine gun was an uncivil weapon to use against European

opponents. Thus Maxim changed his approach and began to market the weapon for

use in the colonies to pacify native colonial populations. Inevitably, cases of

slaughter by machine gun among the major powers’ far-flung colonies tainted the

weapon, making it even less palatable for European warfare in the eyes of many

officers holding traditional ideas toward combat and warfare.

MAKING THE ROUNDS

Undaunted by squeamishness among potential customers, Maxim

traveled Europe while demonstrating his weapon. He was accompanied by Albert Vickers,

a steel producer from South Kensington who had become intensely interested in

Maxim and his invention. In 1887, Maxim took one of his guns to Switzerland for

a competition with the Gatling, the Gardner, and the Nordenfelt. It easily

out-shot all competitors. The next trials were in Italy at Spezzia. There the

Italian officer in charge of the competition requested Maxim to sub- merge his

gun in the sea and allow it to be immersed for three days. At the end of that

time, without cleaning, the gun performed as well as it had before being

subjected to this officer’s unusual demand. The next trial was in Vienna, where

an impressed Archduke William, the field marshal of the Austrian Army, observed

that the Maxim gun was “the most dreadful instrument” that he had

ever seen or imagined. History would

prove the archduke’s observation to be only too true.

Many observers were first skeptical toward Maxim’s claim

that his weapon could fire 10 shots per second and maintain that rate of fire

for any extended length of time. At the Swiss, Italian, and Austrian trials and

those that followed, Maxim made believers out of all who saw the weapon in

action. One exception was the king of Denmark, who was dismayed at the

expenditure of ammunition and decided that such a weapon was far too expensive

to operate, saying that it would bankrupt his kingdom.

In 1888, Maxim formed a partnership with Vickers, an association

that would last until Maxim’s seventy-first birthday. Having successfully

demonstrated his weapon in Europe, Maxim and his new partner began producing

the machine gun. The first production model was capable of firing 2,000 rounds

in 3 minutes. It was very well built, easy to maintain, and virtually

indestructible. By 1890, Maxim and Vickers were supplying machine guns to

Britain, Germany, Austria, Italy, Switzerland, and Russia.

LATER MODELS AND DERIVATIVES

Maxim continued to perfect his weapon. In 1904, he produced

a new model that was the first gun to bear the name Vickers along with Maxim.

The Vickers was stronger and more reliable than its predecessors. Maxim’s

weapons were adopted by every major power in the world at one time or another

between 1900 and World War I.

The success of the Maxim gun inspired other inventors, and guns based on its principles appeared in armies in Germany, Russia, the United States, and other nations. The weapons that would have such a devastating impact on the battlefields of World War I were, largely, direct descendants of the first Maxim design.