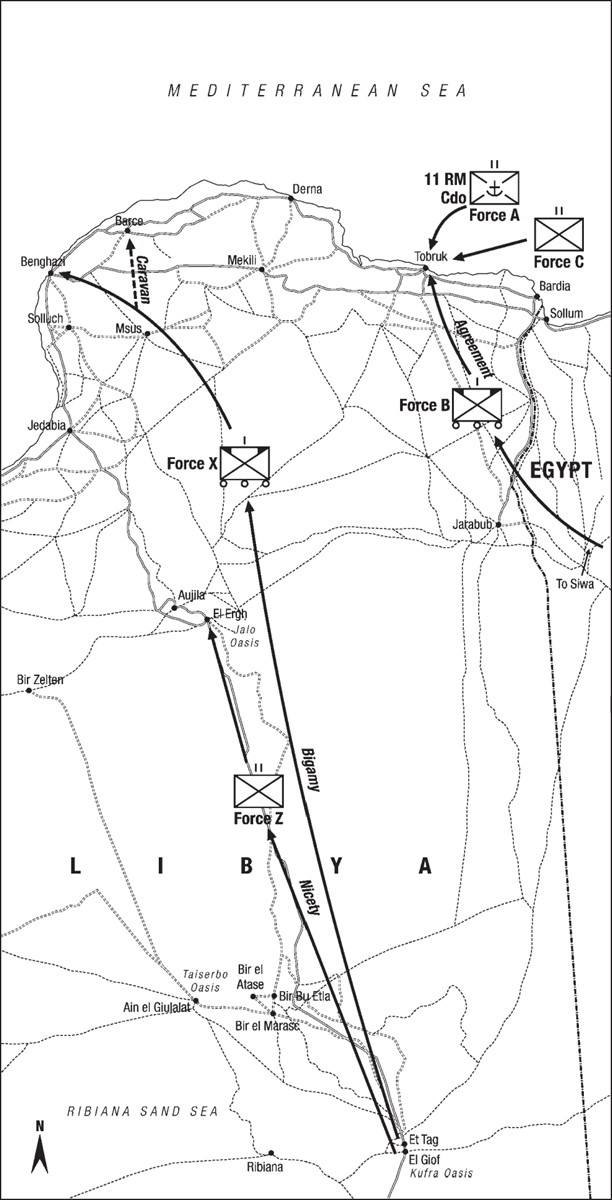

Whilst Tobruk was being attacked, the second raid, Operation

Bigamy, would target Benghazi. This group, dubbed Force X, would comprise

Stirling himself leading L Detachment of 1st SAS marching in 40-odd jeeps,

supported by two LRDG patrols (S1 and S2) with a further detachment of Royal

Marines. Their objectives were still substantial – to block the inner harbour,

sink ships and blast port installations. Mission accomplished, Force X would

retire only as far as Jalo Oasis and launch more raids over an intense,

three-week period.30 At one point, it was proposed to ferry in a full battalion

from Malta and throw in a couple of Honeys. This enlargement was, happily, soon

mainly forgotten.

Another LRDG patrol would guide a unit of the SDF (Sudan

Defence Force) to Jalo Oasis (then in enemy hands), on the night of 15/16

September, in Operation Nicety. It was thought the place was weakly held by

Italians and the SDF was to be beefed up with howitzers, anti-tank and AA guns.

The RAF would bomb Benghazi as well as Tobruk. Planes would sow a harvest of

dummy ‘parashots’ over Siwa, which would be ostensibly threatened by a feint

mounted by SDF. Two more LRDG patrols, led by Captain Jake Easonsmith, would

also attack Barce, purely their affair. This merest of mere sideshows would be

the only successful operation.

Lieutenant Colonel Unwin would lead 11th Battalion Royal

Marines in the amphibious assault. The CO, a mature officer recalled to

service, was described as ‘taciturn but a good leader, bold in nature and

concerned to turn 11 RM into an aggressive commando force’. His battalion had

endured a frustrating war. They’d been raised as part of the Mobile Naval Base

Defence Organization (MNBDO). Their function was to provide and secure

temporary naval havens wherever the need should arise. Employment had been

found for them on Crete in the superb anchorage of Suda Bay, but 11th Battalion

had arrived too late for this deployment; a blessing as it turned out after the

skies over Crete darkened with General Karl Student’s Fallschirmjäger.

Throughout the remainder of 1941, the marines trained around

the Bitter Lakes, possibly once an extended finger of the Red Sea, but they

spent a depressing amount of their time guarding Morscar Barracks. In 1942 they

spent long periods at Haifa, a crucial port and link to the lifeline of

Anglo-Iranian oil. On 15 April they finally went to war in earnest when Unwin

led a company sized force in an amphibious raid on the small island of

Kuphonisi off the south-east tip of occupied Crete.

Their mission was to destroy an Axis wireless station. It

became very lively but they got the job done and left the place wrecked. An

enemy collaborator in the pleasing form of an ample swine was made captive (POW

= ‘pig of war’). This was rich booty indeed. Ironically, the codes and ciphers

they’d filched had already been cracked, but the marines’ larceny prompted the

enemy to change these.

The marines trained aboard the two Tribal Class destroyers

Sikh and Zulu. These were larger type destroyers but they were well above

reasonable capacity when 200 marines and their boats were embarked.33

Land-based fitness training took place in Palestine, Trans-Jordan and Egypt.

The men were strong and they were ready. The difficulty lay in how they might

be got ashore. Clearly, this is the critical element in any amphibious

operation, and has exercised commanders since the Siege of Troy. The plans for

Waylay had favoured purpose built timber craft as opposed to ships’ boats. On

paper this made sense. In practice it did not, as Major Mahoney recalled:

The selected small craft dumb lighters towed by small

powered craft, and these small three ply power boats with their dumb lighters

were all the contemplated boats for the landing. They were pathetically slow

and subjected mainly to fouled propellers in shallow waters during exercises.

Nobody liked the boats, as Gunner Wilson stated:

We first practiced the landings at Cyprus with these

special boats built in Lebanon, and the ‘Sikh’ could carry about half a dozen

of these I think. They were built with green Lebanon wood and were extremely

fragile and far from handy … As far as I can remember they were not very

long, about fifteen to sixteen feet and very lightly built of wood on steel

frames.

Here lay the problem, the fatal flaw. The concept for

getting the marines ashore was wrong from the start, as it involved cheap nasty

little boats, barely seaworthy in calm water, far less so in rough. This

tactical design failure would come back to haunt the execution of Operation

Agreement. The marines did not fail, but these shoddy excuses for landing

craft, or ‘shoeboxes’, did for them as surely as any Axis guns.

This was bad, but the security situation was worse, as

Fitzroy Maclean remembered:

For obvious reasons, secrecy was vital, and only a very

small number of those taking part in the operations were told what their

destination was to be. But long before we were ready to start there were signs

that too many people knew too much. At Alexandria a drunken marine was heard

boasting in a canteen that he was off to Tobruk; a Free French officer picked

up some startling information at Beirut; one of the barmen at the hotel, who

was generally thought to be an enemy agent, seemed much too well informed.

Worse still, there were indications that the enemy was expecting the raids and

taking counter measures.

If surprise was the key, then so was secrecy. If the enemy

got wind of the plan, the game was effectively up. That Tobruk was a likely

target required no hint of genius. Intelligence is at the heart of all

successful operations. So far the Allies, thanks to the brilliance of the

Bletchley code-breakers, were doing rather well. The arrival of Rommel in the

North African Theatre coincided with the establishment of a special signals

link to Wavell and Middle East Command in Cairo. Hut 3 at Bletchley could now transmit

reports directly to the GOC. Ultra intelligence was not able to identify

Rommel’s immediate counter-offensive, but Hut 6 had broken the Luftwaffe key

now designated ‘Light Blue.’ Early decrypts revealed the concern felt by OKH

(Oberkommando des Heeres) at Rommel’s maverick strategy and indicated the

extent of his supply problems.

Though the intercepts were a major tactical gain in

principle, the process was new and subject to delay to the extent that they

rarely arrived in time to influence the events in the field during a highly

mobile campaign. Equally, Light Blue was able to provide some details of Rommel’s

seaborne supplies but again in insufficient detail and with inadequate speed to

permit a suitable response from either the RN or RAF.

Then, in July 1941 a major breakthrough occurred. An Italian

navy cipher, ‘C38m’, was also broken, and the flood of detail this provided

greatly amplified that gleaned from Light Blue. Information was now passed not

just to Cairo but to the RN at Alexandria and the RAF on Malta. Every care, as

ever, had to be taken to ensure the integrity of Ultra was preserved. Jim Rose,

one of Bletchley’s air advisors, explains:

Ultra was very important in cutting Rommel’s supplies. He

was fighting with one hand behind his back because we were getting information

about all the convoys from Italy. The RAF were not allowed to attack them

unless they sent out reconnaissance and if there was fog of course they

couldn’t attack them because it would have jeopardised the security of Ultra,

but in fact most of them were attacked.

Ultra thus contributed significantly to Rommel’s supply

problem. On land a number of army keys were also broken; these were designated

by names of birds. Thus it was ‘Chaffinch’ that provided Auchinleck with

detailed information on DAK supply shortages and weight of materiel including

tanks. Since mid-1941 a Special Signals Unit (latterly Special Liaison Unit)

had been deployed in theatre. The unit had to ensure information was

disseminated only amongst those properly ‘in the know’ and that, vitally,

identifiable secondary intelligence was always available to mask the true

source.

Experience gained during the Crusader offensive indicated

that the best use of Ultra was to provide detail of the enemy’s strength and

pre-battle dispositions. The material could not be decrypted fast enough nor

sent on to cope with a fast changing tactical situation. At the front,

information could be relayed far more quickly by the Royal Signals mobile

Y-Special Wireless Sections and battalion intelligence officers, one of whom,

Bill Williams, recalled:

Despite the amazing speed with which we received Ultra,

it was of course usually out of date. This did not mean we were not glad of its

arrival for at best it showed that we were wrong, usually it enabled us to tidy

up loose ends, and at least we tumbled into bed with a smug confirmation. In a

planning period between battles its value was more obvious and one had the

opportunity to study it in relation to context so much better than during a

fast moving battle such as desert warfare produced.

Wireless in the vastness of the desert was the only

effective mode of communication, but wireless messages are always subject to

intercept. Bertie Buck’s Jews from Palestine provided specialist skills. Most

were German in origin and understood only too well the real nature of the enemy

they faced. The Germans had their own Y Dienst (Y Service) and the formidable

Captain Seebohm, whose unit proved highly successful.

The extent of Seebohm’s effectiveness was only realized

after his unit had been overrun during the attack by 26th Australian Brigade at

Tell el Eisa in July 1942. The captain was a casualty and the raiders

discovered how extensive the slackness of Allied procedures actually was. As a

consequence the drills were significantly tightened. If the Axis effort was

thereby dented, Rommel still had a significant source from the US diplomatic

codes, which had been broken and regularly included data on Allied plans and

dispositions, the ‘Black Code’.

Reverses following on from the apparent success of Crusader

were exacerbated, as Bletchley historians confirm, by ‘a serious misreading of

a decrypt from the Italian C38m cipher’. Hut 3 could not really assist the

British in mitigating the defeat at Gazala or, perhaps worse, the surrender of

Tobruk. This was one which Churchill felt most keenly as ‘a bitter moment.

Defeat is one thing; disgrace is another’.

Until this time it had taken Bletchley about a week to crack

Chaffinch, but from the end of May, the ace code-breakers were able to cut this

to a day. Other key codes ‘Phoenix’ and ‘Thrush’ were also broken. Similar

inroads were made against the Luftwaffe. ‘Primrose’, employed by the supply

formation and ‘Scorpion’, the ground/air link, were both broken. Scorpion was a

godsend: as close and constant touch with units in the field was necessary for

supply, German signallers unwittingly provided a blueprint for any unfolding

battle.

On the ground 8th Army was increasing the total of mobile Y

formations, whilst the intelligence corps and RAF code-breakers were getting

fully into their stride.40 None of these developments could combine to save the

Auk, but Montgomery was the beneficiary of high level traffic between Rommel

and Hitler, sent via Kesselring (as the latter was Luftwaffe). The Red cipher,

long mastered by Bletchley, was employed. Monty had already predicted the

likelihood of the Alam el Halfa battle, but the intercepts clearly underscored

his analysis.

By now the array of air force, navy and army codes

penetrated by Bletchley was providing a regular assessment of supply, of

available AFVs (Armoured Fighting Vehicles) and the dialogue of senior

officers. The relationship between Rommel and Kesselring was evidently

strained. Even the most cynical of old sweats, Bill Williams, had cause to be

impressed: ‘he [Montgomery] told them with remarkable assurance how the enemy

was going to be defeated. The enemy attack was delayed and the usual jokes were

made about the “crystal-gazers”.’ A day or two later everything happened

according to plan. Ultra was dispelling the fog of war.

In some ways, the Desert War provided the coming of age for

the Bletchley Park code-breakers, as intelligence officer Ralph Bennett

explains:

Until Alam Halfa, we had always been hoping for proper

recognition of our product … Now the recognition was a fact and we had to go on

deserving it. I had left as one of a group of enthusiastic amateurs. I returned

to a professional organisation with standards and an acknowledged reputation to

maintain.

By the time of Agreement, the Allies were getting ahead in

the intelligence and ciphers game. What would let them down, and what to some

extent remains controversial, was the apparent total lack of secrecy

surrounding planning and preparation for the mission.

Fitzroy Maclean was not the only one hearing rumours. J. J.

Fallon, a Royal Marine, recalled ‘friends telling me their destination; it was

equally common knowledge in the cafes and bars together with the clubs

frequented by servicemen’. On 2 September, Lieutenant Colonel Unwin had

dispatched a corporal of his 11th Battalion from Haifa to the combined training

centre at Kabret to pick up some kit. Later that same day, the wretched NCO was

overhead gabbling in the NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institute). He had

recounted details of a supply convoy he passed, talked about the gear he had

transported and where it was going. He confided that a big ‘op’ was imminent

involving destroyers and hundreds of marines. He speculated this was an

outflanking expedition aimed at Halfaya and more. He soon found himself in very

serious bother, but the damage may have been done.

‘Loose talk cost lives’ – an always true wartime saying, and

yet to what extent loose talk compromised the operation is very hard to judge.

Gossip generally doesn’t leave traces in any archives. Marines were warned not

to appear on deck in their battledress while the destroyers were berthed at

Alexandria. This was probably too little and far too late.45 Stirling

emphatically denied any leak emanating from his SAS, Guy Prendergast would have

been equally vehement on behalf of LRDG, and both would very probably have been

right. Those at the sharp end know their lives depend on secrecy. It’s those

behind who are never at risk who might blab.

Stirling was adamant that the problem was to be found in the

clubs and bars of Cairo. David Lloyd Owen warned Haselden that the bazaars were

buzzing and the latter agreed, though he was hopeful the Axis would not have

picked up sufficiently on the chatter. Rear Admiral L. E. H. Maund, serving

with combined operations, was more specific in his allegations. He asserted

that security within LRDG HQ at Kufra was lax and details of the mission were

being openly discussed there, and that the presence of SIG personnel in German

gear was common knowledge.

At the other end of the operational zone, talk at Haifa

focused on the marines. Gossip breeds rumour, which leads to speculation and

debate, practically as good as a signed copy of the operational orders for any

lurking Axis agents. Moving the entire contingent, men, ships and supplies to

Kabret, which could be effectively sealed off, was considered and then

rejected. A New Zealand officer stationed at the divisional base outside of

Cairo was apparently heard openly discussing the operation.

There was an element of comic opera when laundry-men bringing

the men’s shirts back aboard the ships were demanding immediate settlement ‘as

you go to Tobruk’! This was hardly calming. Did the Axis in fact know? This is

uncertain. There is some anecdotal evidence suggesting a heightened awareness,

but no specific proof that security in Tobruk was beefed up to any extent.

Surely if the enemy did know, then Haselden’s party would never have passed

through the wire unchallenged, as they were to do. The Operational History is

emphatic that there is no evidence of Axis foreknowledge, and nothing of the

actual events suggests they were in any way primed.

Nonetheless, this was potentially very bad. Despite the

Allies’ capacity for successful eavesdropping and accurate reporting, knowledge

of the actual garrison strength at Tobruk was very thin indeed, and based, as

it appeared, mainly upon wishful thinking. It was estimated that the Italians

might have a weak brigade with perhaps a battalion of Germans. Optimistically,

it was suggested that most of these would be bivouacked some way above and

outside the town. Nor was it considered likely the Axis possessed sufficient MT

(motor transport) to bring their men in.

If information on troop strengths was scanty, assessments of

attack aircraft available both from the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica were

far more accurate. Intelligence suggested the latter could deploy some 30

Macchi 200 fighters from El Adem and Tobruk aerodromes and two dozen torpedo

bombers at Derna, with some Ju 88s and Me110s. Another 30 Ju 87 Stukas could be

scrambled from Sidi Barrani and be on target within the hour.

Within a couple of hours’ flying time, the Germans could

fill the skies with planes from Crete and other airfields, an offensive total

of some 130 aircraft. The raiders would be at high risk during daylight, even

if they could take and mount the port’s complement of AA guns. The marines had

been blandly assured that the RAF had the matter in hand. There was no detail

on this and Air Marshal Tedder’s* objections to the whole scheme were based on

the lack of Allied fighter cover. This planning gap was to produce fearful

consequences.

What would be of considerable value to the mission was up to

date aerial reconnaissance. If the planners could get their hands on a full

photographic survey in 1:16.800 scale this would reveal the extent of any new

defences, new dumps and camps, enhanced transport and railway links, and, as a

useful bonus, would corroborate (or show the lack of) the accuracy of current

maps. This intelligence would be a tremendous boon, and Brigadier George Davy

entreated the RAF to oblige via their Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) on

30 August. His request came with a health warning in that increased air traffic

over the port might alert the enemy. In any event the PRU was too busy to

comply: as the commanding officer put it, ‘the existing operational commitments

of PRU aircraft can barely be met with present resources … I cannot place the

demand for special photography of the Tobruk area on the highest priority from

any given date.’

This was not helpful, but such a recce might not have

provided much useful information anyway. The photos would have enabled the

planners, and therefore the participants, to build up a better picture, but it

appears unlikely this would have had an impact on the final outcome. Training

and preparation were in the event inadequate, the landing boats were totally

unsuitable and the entire scheme hopelessly over-reliant on a series of

disconnected elements coming together.

Unwin’s marines would deploy an HQ section with

communications detachment, A, B and C companies of the 11th, an MG (machine

gun) platoon, mortar platoon, attached gunners, sappers and medics. All would

wear light desert kit with commando boots and carry bare rations and water.

This was ideal fighting gear, and having everyone dressed the same would reduce

the risk of ‘blue on blue’ incidents. Additional stores of ammunition (100,000

rounds of .303, 100 3-inch mortar rounds, 200lb of gun-cotton slabs with 50

primers) were to be off-loaded on No. 4 jetty by late morning.

Before a single marine was able to come ashore, the landing

beach would be marked by an SBS detachment using Folbots. Lieutenant Kirby was

in charge of the canoeists who, with their boats, would be carried on the

submarine Taku. They would ship out from the sub at 0130 hours and Taku would

signal the destroyers at 0200 hours that the SBS team was safely ashore. Once

on the beach at Mersa Mreira, Kirby would set up the landing lights: one would

be placed on the eastern flank of the cove entrance, the other half way down

the passage on the same side. Two long flashes would be sent out every two

minutes from NE to NW from 0245 hours and keep flashing till the landing boats

were safely in. A red light meant all clear; white spelled danger.

Both destroyers would disembark their marines in the small

lighters, strings of which would be pulled by the motorized launches. Marines

were to be ashore at Mersa Mreira by 0330 hours, sorted, formed and moving on

their objectives within 45 minutes. It was A Company’s job to secure the outer,

west-facing perimeter. C Company would move against the coastal gun positions

at Mengar Shansak, taking these and German AA guns alongside. Having

neutralized these they would probe westwards, rolling up the outer batteries

till they had reached the No. 4 jetty. This would allow the sappers to begin

their work of destruction. The mortars would go with C Company, but could be

retrieved by battalion HQ to attack enemy positions wherever they needed

battering.

While A and B companies were thus gainfully employed, B

Company would head straight for the town centre, sweeping up AA positions en

route. This done, they’d look to the ravaging of the MT workshops and

facilities. Once the Argylls were put ashore on the eastern flank from Force

C’s MTBs, they would reinforce the western perimeter. C Company of the marines

would redeploy in support, leaving three full companies to hold the rim. B

Company of the marines would support the Scots but, at the same time, were

tasked to effect the liaison with Haselden’s Force B. The demarcation line

between the seaborne units and Force B would be the road that linked the

hospital to the western extremity of the quays. Essentially, the regular

infantry, beefed up by the Fusiliers’ MG platoon, would secure the area whilst

the specialists continued blowing things up.

Part of the intended booty comprised the numerous SFs or

Siebel Ferries; squat, square and ungainly, these workaday lighters were ideal

for the movement of supplies from ship to shore. They each carried their own

light AA guns and it was hoped to net at least ten of them. Those that could be

cut out were to be dispatched eastwards, and those that couldn’t were to be

sunk to the bottom of the harbour. Once the blowing up was finished, Force B

would send up a multi-coloured flare, a signal for the British ships and MTBs

to enter the port, confirmed by radio. Casualties would either be shipped out

to the destroyers by captured ferry or, if too badly wounded, handed over to

the Italian hospital. By 1900 hours the entire force was to be up and away.

With their initial, vital mission complete, the SBS team

would pitch in with the marines targeting the harbour and cutting out the

German lighters. Taku, having launched her cargo, would steam clear at top

cruising speed and stand to some 40 miles offshore. Once the port itself was

secure, this would be the trigger for the two destroyers to enter. Both Sikh

and Zulu had been cannily camouflaged to look like Italian craft. Once they got

into the harbour, they would list over to one side and pump oil, accompanied by

ample outpourings of black smoke; the guns would be depressed and upper decks

kept clear.

The purpose of all this mummery would be to give the

impression the destroyers were already crippled and out of action. This, it was

fervently hoped, would be sufficient to persuade any nosey Stukas that they

weren’t viable or hostile targets. Some would argue Allied fighter cover might

have served rather better. This was all both very complicated and

inter-dependent. And this was just Force A. The marines could not accomplish

their part without the other two main elements fulfilling theirs.

John Haselden, often viewed as the prophet of Operation

Agreement, would lead Force B. This was the stuff of Henty. The unit would

attack from the landward side after an epic desert crossing. The colonel’s

friend and admirer David Lloyd Owen, with Y1 Patrol of the LRDG, would guide 83

commandos from D Squadron Special Service Group, commanded by Major Colin

Campbell of the London Scottish. The raiders, with added detachments of

gunners, sappers and signallers, would be crammed into eight 3-tonners. LRDG

would rely on their tested and more nimble Chevrolets. Lieutenant Poynton, the

RA (Royal Artillery) officer, had a tough assignment; he and his very modest

squad were expected to man the captured guns while Lieutenant Barlow would look

to AA defence. Bill Barlow had in fact served during the siege of Tobruk, so

possessed considerable personal knowledge, likely to be an invaluable asset.

The SBS contributed Lieutenant T. B. Langton, an ex-Irish

Guards officer, who as well as being adjutant had the vital task of signalling

to Force C, the MTB-borne detachment offshore, that the vital cove had been

secured. Without this confirmation they could not land. Lieutenant Harrison

commanded the sappers, charged as ever with the blowing up of things, and

Lieutenant Trollope led the signals section. The team also fielded a lone

representative of the RAF, Pilot Officer Aubrey L. Scott, responsible for

liaison.

Bertie Buck with Lieutenant David Russell of the Scots

Guards was in charge of the tiny SIG squad. As they had previously at Derna,

the SIG troopers would pose as German guards, the commandos their POWs. This

ruse, it was hoped, would get them through the perimeter wire. If they were

closely challenged, the SIG would be close enough to the sentries to ensure

they caused no further difficulties. Russell, like Buck, was a fluent German

speaker.

Peter Smith, incorrectly, lists two further British

officers, a Captain Bray and Lieutenant Lanark. These men did not in fact

exist. Gordon Landsborough in his 1956 classic Tobruk Commando assigns these

names to Buck and Russell. At the time of Smith’s writing, certain War Office

restrictions still applied and the use of these noms de guerre was a necessary

literary fiction. Likewise, Landsborough lists the four other ranks as Corporal

Weizmann (real name Opprower), privates Wilenski (probably Goldstein), Berg

(30777 Private J. Rohr or Roer) and Steiner (10716 Corporal Hillman 1 SAS).

There was also a Private Rosenzweig.

The SIG behaved, spoke and were equipped as Germans; their

love letters, carefully written, were also in German. Opprower called his

fictitious girlfriend Lizbeth Kunz, in fact an ardent Nazi and near neighbour

of his before he fled the Fatherland.56 Buck tested his men relentlessly. Their

cover stories had to stand up, though none could be in any doubt as to their

likely fate if they fell into Axis hands. After the previous debacle, the

Germans were aware of the unit’s existence. As a bonus, Buck did entertain

hopes, in Stanley Moss/Patrick Lee Fermor style, of seizing a German general

who had a billet in the town!

This was the reason Buck took only one other officer and

five soldiers with him. The bluff really needed around a dozen to look totally

convincing. Operation Agreement did not succeed, but the SIG did. Their role in

the mission was absolutely critical. If the bluff failed, if Force B had to

fight their way in, the whole plan would be unravelling from the start. As a

sub-unit, they kept themselves apart; the commandos frankly preferred this.

Since the earlier betrayal, the whole unit was looked on with suspicion.

Haselden had his own pet project once inside the wire, which would involve

releasing the thousands of Allied POWs who it was believed were being held in

large holding areas (‘cages’) inside the defences. Popski was cynical from the

start, or perhaps this was providential hindsight; success, as they say, has a

thousand fathers, but failure is always an orphan!

So much for land and sea: what of operations in the skies?

The RAF was due to appear overhead at 2130 hours on D1 and the raid would

continue to 0330 hours on D2, though no flares would be dropped after 0100

hours. It would be massive, one of the biggest of the Desert War. The northern

flank would get the heaviest pounding, and even once the raid was ended a

number of planes would stay in the air above the harbour until 0500 hours to

keep the AA guns and radar fully diverted. It was hoped, as mentioned, that the

fury of the bombardment would drown the noisy approach of Force C’s MTBs.

Another job for Force B’s signaller was to set up a marker

at Mersa Umm Es Sciausc. This was a very large triangle with sides 20 yards

long, lit by three glim lamps with the signal ‘OK’ being flashed from an Aldis.

Once this was sighted, the planes would return their acknowledgement ‘TOC’ and

then transmit the codeword for success, ‘Nigger’ (this was considered an

acceptable term at the time), to Captain Micklethwait. The RAF also hoped to

bomb other Axis airfields along the coast and drop a few bombs on Crete for

good measure (Crete was subsequently taken off the hit-list as a target too

far, given the resources available).

Admiral Harwood, whose reduced fleet bore the lion’s share

of eventual losses, described the operation as ‘a desperate gamble’. He

acquiesced because he felt he had no choice, yet one feels his predecessor, the

brilliant Admiral Cunningham, would have rejected the whole business. Operation

Agreement, like other strategic failures grew and acquired an irresistible

forward momentum all of its own. Wise counsels were not sought or heeded.

Subsequent, equally ill-judged intervention in the Dodecanese in 1943 was

another example of hasty and inadequate planning, as was, most clearly, the

Arnhem disaster the following year.

Yet not all were necessarily caught up in the unbridled

enthusiasm for Agreement. On 29 August, the joint planners published a very

sober assessment of the likely consequences, not of failure but of success. The

overall effect on the Axis’s maintenance position if the capacity of Benghazi

was curtailed would be minimal unless Tobruk was effectively neutralized. Raids

carried out in the Jebel Akhdar would have little beneficial effect, as the

enemy had moved the bulk of his operations and supply eastwards. Substantial

reserves had been accumulated both inside Tobruk and to the east, enough for up

to a fortnight if normal traffic and supply through the port, measured daily,

matched consumption. Assuming that the harbour could not be effectively blockaded

and thus denied to the enemy, it would be unlikely to remain out of use for any

more than a week and any lighters lost could be replaced. At best, then, the

operation, if it achieved its objectives, would inconvenience the Axis for a

very short time only and oblige them to live off their stores.59 In the light

of so downbeat an assessment, the overall worth of the operation was

questionable from the outset. Derring-do is laudable and boosts morale, but

only if it produces tangible results.