Although the presence of the imperial administration and

court in Sicily was brief, Constantinople continued to send officials,

messengers, and administrators to Sicily on a regular basis. Many official

visits to Sicily from Constantinople were occasioned by violent incidents and

rebellions on the island, much like the one following Constans II’s

assassination. For example, Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818) notes in his

Chronographia that in 718 Emperor Leo III (r. 717–741) dispatched to Sicily a

man named Paul, whom he appointed to be the stratēgos (general) for the island.

Paul traveled with a group of imperial guards charged with regaining control

over the island after Sergius, the previous governor, had rebelled against

Constantinople and declared a rival emperor in Syracuse. This Sicilian

rebellion took place during a massive Muslim siege of Constantinople (717–718),

but the emperor was nonetheless willing and able to dispatch officers to quell

it and thus maintain control over the government of Sicily. He clearly

considered it to be in the empire’s best interest to deploy the resources

necessary to do so, even in the face of threats to the imperial capital, a

conclusion suggesting that the loss of the western frontier would also threaten

the center of Byzantium.

The final outcome of this story, and its analysis by

Theophanes, shows that the maintenance of order in and control of Sicily was of

central importance for the entirety of Byzantium’s western possessions. The

rebel Sergius fled to the Lombards in Calabria, leaving behind his puppet

emperor Basil (renamed Tiberius), whom the imperial appointee Paul beheaded

alongside the rebellious generals. Those heads were sent back to Constantinople

while Paul remained on the island to enforce order. According to Theophanes,

“As a result, great order prevailed in the western parts … all the western

parts were pacified.” Pacifying Sicily was thus equated with bringing order to

all of Byzantium’s western holdings.

Sergius’s rebellion was not the only such uprising on the

part of the Sicilian Greek leaders. Sicily’s significant distance from

Constantinople, and its position at the edge of the empire, meant that, despite

imperial efforts to control the island, it was in a prime location for those

wishing to break free from Byzantine central authority. Likewise, the relative

independence from Constantinople of the southern Italian Greek cities may have

provided a model for the aspirations of Sicilian governors hoping for greater

local power. In 780/781, for example, the Sicilian ruler Elpidios rebelled

against imperial authority after having been in office only a few months. In

response, the empress Irene (regent, 780–797, regnant, 797–802) commanded a

spatharios (a member of the imperial guard) named Theophilos to sail to Sicily

and arrest Elpidios, but the Sicilians refused to hand the latter over. The

following year, Irene sent to Sicily an entire fleet, led by an official named

Theodore, to put down the revolt; the Byzantine forces at last triumphed over

the rebels.

The latter rebellion took place during a period of peace

between Byzantine Sicily and Muslim North Africa—a pause in the semiregular

raids on Sicily’s southern shores. This peace between Syracuse and Qayrawān was

one of several treaties that halted the regular raiding parties from Egypt and

Ifrīqiya that had been attacking the island for around a century by that point.

The initial aim of these raids does not appear to have been the conquest of the

island, but rather the collection of booty and slaves. Nonetheless, Greek

Sicily was facing regular security threats that prompted Constantinople to

increase its grip on the island. The late eighth century was a time when

Constantinople tried to preserve Sicily as a Byzantine stronghold in the

Mediterranean, perhaps fearing that the island’s loss would spell the end of

Byzantine power in the western Mediterranean. At the time, Byzantium maintained

only loose control over other formerly Greek lands in Italy, having lost direct

influence in the majority of southern Italy. Even the Exarchate of Ravenna had

been drifting away from Greek control and functioned independently in many

arenas; it would fall to the Lombards in 751, leaving Sicily as the last

holdout of direct Byzantine power in the West. Despite Irene’s successful

defense of Sicily against internal rebellion, less than fifty years later the

island would fall under Muslim control, and Constantinople would never again

wield great influence in the western Mediterranean. The imperial government

could not know this future, however, and the continued efforts (even until the

eleventh century) to reclaim the island demonstrate Sicily’s centrality in the

Byzantine agenda.

That said, not all of the acts of travel between

Constantinople and Syracuse indicate the island’s importance to the empire; in

fact, some imply nearly the opposite. At several points during the eighth

century’s political tumult, for example, Sicily served as a place of exile for

political rebels whom the Byzantine ruler wanted to keep far away from the

political center of Constantinople. Theophanes’s Chronographia mentions several

cases of political exiles who were sent to Sicily so that they could not

continue to cause trouble in the imperial capital. Despite the island’s history

as a site of repeated rebellions, Sicily presented itself to some emperors as

an expedient spot for marginalizing political troublemakers. In these cases,

the distance between the two locations was key to the effectiveness of the

political move.

In 789/790 both Emperor Constantine VI (780–797) and his

mother, Empress Irene, banished their political rivals to Sicily. Constantine

VI likewise sent rebels to exile on this and other islands in the year 792/793.

Distance and relative inaccessibility were vital for keeping an exiled person

far from the center of political power. However, because Constantinople

maintained regular communications with Syracuse, it was possible for the rulers

to remain aware of the activities of their exiles. It is important to note that

Sicily was not the only location chosen for receiving political deportees, as

there were many islands closer to Asia Minor that routinely served as places of

exile, such as the Princes Islands in the Sea of Marmara and Aegean islands

such as Patmos. In some cases, Sicily may have been preferred because a

particular governor of Sicily was deemed to be trustworthy in safeguarding

against rebel activities. In any event, the island was both geographically far

from the capital and conceptually near to it—near enough that the imperial

government could keep a close watch on its rivals’ actions, by means of

established networks of communication. Thus, it seems, Sicily could be

considered both close to and far from Constantinople, depending on the

political need.

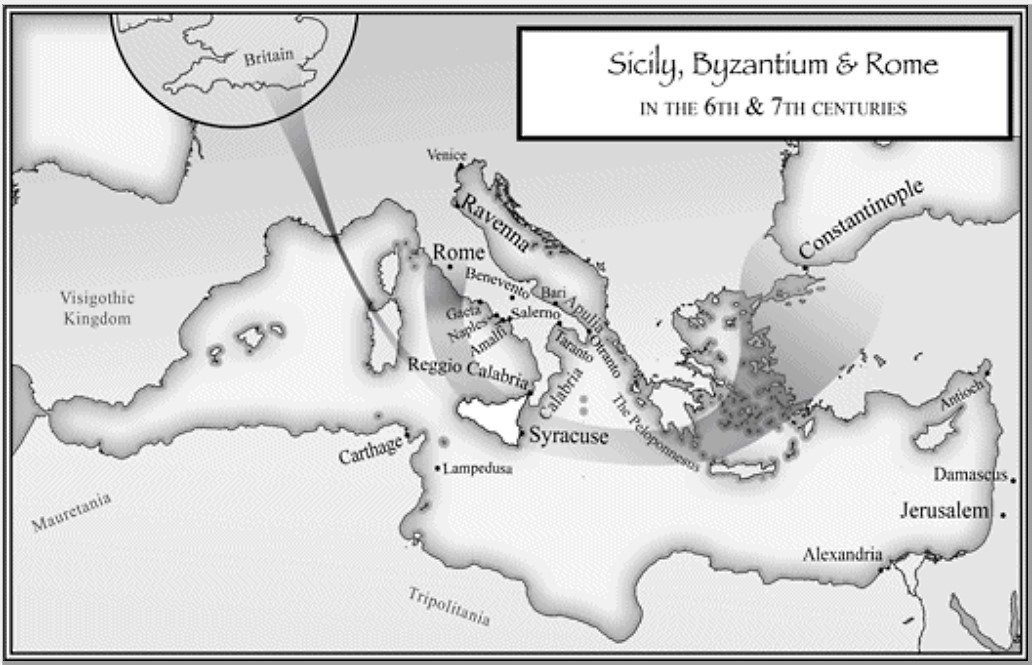

While geographically distant from Constantinople, the island

was directly adjacent to Greek-claimed territories in southern Italy. Proximity

to these Greek regions of southern Italy was thus another advantage Sicily had

in its political utility for Constantinople. During its years under Byzantine

rule, Sicily often functioned as a link between Constantinople and the

Byzantine territories in mainland Italy, both as a transit point for messengers

and as a base for enforcing order in Italy, particularly when the mainland

Greek cities were more successful in their efforts to establish their

independence from imperial rule. Greek imperial officers often sailed to Sicily

and stayed there briefly before taking the land or sea route to Greek lands in

Italy.

One example of Constantinople’s use of Sicilian government

officials against Byzantine territories in Italy occurred around the year 709.

Felix, archbishop of Ravenna (r. 705–723), attempted to liberate his city from

Byzantine rule, and so Emperor Justinian II (669–711, r. 685–695 and 705–711)

sent the governor of Sicily, Theodorus, to take hold of Felix and the rebels.

Theodorus and the Greek fleet sailed from Sicily to Ravenna to carry out the

order. He arrested and shackled the rebels aboard a ship, alongside the riches

they had purportedly stolen, and sent them to Constantinople. Felix was exiled

to Pontus until around 712, when the next emperor, Philippicus, restored him to

the church in Ravenna and had him sent back there with an escort, again by way

of Sicily. Sicily does not necessarily lie on the most obvious route between

Ravenna and Constantinople, and, notably, other trips between the two cities

did not always involve Sicily. Therefore, on these trips there must have been

compelling but unstated reasons for the entourage to stop on the island. It is

not clear from the text if Sicilian officials were involved in this return trip

or why Sicily was the chosen route between Constantinople and Ravenna.

Nonetheless, this anecdote allows us to see Sicily and its officials as key

factors in Constantinople’s attempts to maintain power in southern Italy, even

when geography was not the determining reason for using Sicily as a way station

along the journey.

The Royal Frankish Annals contain a reference to similar

activity in the year 788. It is recorded that Emperor Constantine VI ordered

the governor Theodorus to destroy the city of Benevento in revenge for the

emperor not having received Charlemagne’s daughter as his wife. The Byzantine

forces traveled from Sicily to Calabria, where they met the Frankish-allied

Beneventan troops in battle but were defeated. Thus we again see a Sicilian

governor tasked with carrying out imperial edicts on the mainland. While its

placement close to mainland Italy certainly made the island useful

geographically, the presumed ability of the island’s officials to raise

appropriate armies and attack the mainland, along with the trust the emperor

placed in those distant representatives to carry out such campaigns,

demonstrates the island’s conceptual utility to the Byzantine Empire. Sicily

was not simply a distant province at the periphery of the empire but was at

times an integral extension of the central authority of Constantinople.

In general, then, early medieval Sicily’s communications

with Constantinople show the island in a number of important roles: a site of

political rebellion and exile, an agent of imperial authority within Italy, and

a stronghold of Byzantine power along the vulnerable three-way border at the

far western edge of the empire. Sicily and its governors acted in the West as

an extension of Constantinople, relying on a steady stream of officials, news,

messengers, and troops between the capital and the island. The island also

functioned as a specific site of imperial authority when it was the temporary

capital of the empire under Constans II, and even though this was a brief and

isolated instance, it demonstrates the multiple ways in which Sicily was deemed

central to the goals and safety of the Byzantine Empire as a whole. As the

bulwark of Byzantine power in the central Mediterranean, Sicily both protected

the empire’s western edge and represented imperial authority in the region.

And, in the case of revolt against Constantinople, the island could serve as a

base for rival power and as a stepping-stone to the center of the empire: if

rebels were to gain power on the island, they might be able to use the

established relationship between Syracuse and Constantinople to assert their

claim to authority over all of Byzantium. Even when the emperors were

distracted by business closer to home, the imperial authorities strenuously

worked to maintain their hold over Sicily. By keeping control of this island

borderland, the Byzantines were able to use Sicily in the enforcement of their

will in Italy as well as in diplomatic relationships with sites of power in the

Latin world, Rome, and the Frankish court (represented by Aachen) and, after

the mid-seventh century, with the new centers of Muslim power in North Africa.

While Sicily functioned as an important Byzantine borderland

in the western Mediterranean and maintained close communications with

Constantinople, ties between Sicily and Rome and the Latin world also remained strong.

Having been a Roman province for several centuries, the island featured a

population with many Latin speakers and numerous Latin churches. Due also to

the persistence of communication networks between Rome and Sicily, the island

was never fully detached from the Latin West in terms of culture, religion,

and, to some degree, politics. Simply because the island shifted from Roman to

Germanic and then to Greek administration does not mean that cultural or social

connections between the island and Rome were severed. The endurance of these

links is partly due to the continued presence of a Latin population and the

maintenance of papal estates on the island, and many Sicilians remained

adherents of the Latin Church. Simultaneous connections to Rome and to Constantinople

allowed the island to function, in some ways, as part of both the Latin and

Greek worlds and therefore as a vital point of connection between them. Thus,

in addition to functioning as a link between Constantinople and the

Byzantine-claimed territories in mainland Italy—both as a transit point for

messengers and as a base for enforcing order in Italy—Sicily could serve as a

mediator in communications between Constantinople and Rome.

Indeed, Sicily functioned as an important node in the networks

of communication that existed between emperors in Constantinople and popes,

kings, and emperors in the West. In terms of papal-imperial business and

diplomacy, Sicily appears to have been a regular stop on the route between

Constantinople and Rome, although it was not the only path for information or

messengers between the two places. Official and political business between Rome

and Constantinople was conducted often by way of Sicily and, it appears, less

often via an overland route. Many early medieval travelers between

Constantinople and Italy made Sicily a way station on their travels, even if

their business did not directly involve the island. For example, in 653 Pope

Martin I (649–655) was arrested in Rome and taken by ship to Constantinople. The

journey, which lasted from the middle of June until mid-September, followed a

route through Sicily as well as many other Mediterranean ports. In this case,

even though the affair had nothing to do with Sicily, a Sicilian Byzantine

official was involved in the delegation sent to Ravenna. A similar journey took

place in 709, when Pope Constantine (708–715) answered a summons by the

Byzantine emperor Justinian II to appear at Constantinople. The papal party, as

detailed in the pope’s vita in the Liber Pontificalis, journeyed to the

Byzantine capital by way of Sicily, although their return trip did not follow

the same route, and they skipped Sicily on that second leg. Evidently,

therefore, various itineraries were available for travelers between mainland Italy

and the Byzantine capital during the early eighth century. Sicily was, however,

an obvious choice of route when the pope and his entourage were traveling on

the orders of the Byzantine emperor or through the political agency of Sicilian

officials—even when they did not have any particular business to transact on

the island. This fact may have been due to a larger number of

Constantinople-bound ships sailing from Sicilian ports than from other ports in

Italy. Likewise, Sicily’s importance as a transit point for papal-imperial

business may have resulted from the involvement of Greek Sicilian officials as

representatives of the imperial government. In either case, officials

frequently chose routes involving Sicily over other routes to Constantinople;

that is, Sicily often found itself at the nexus of Byzantine-Latin

relationships even when a stopover there was not necessitated by the

involvement of Sicilian personnel.

There is also evidence that, during the seventh through

ninth centuries, Roman Church officials traveled to Sicily on administrative

business that did not involve transactions with Greeks. Representatives of the

Latin Church at Rome traveled to the island to govern the Latin churches there

and the agricultural lands in papal estates. The papal patrimony in Sicily was

concentrated in the cities of Syracuse and Palermo, and some Sicilian lands

were also held by the churches of Milan, Ravenna, and other mainland Italian

cities.33 Latin sources show that early medieval popes frequently traveled to Sicily,

either personally or via their officials, on routine affairs of land and church

administration. Papal visits to Sicily are recorded from the sixth century and

continued at least through the eighth century. One of the earliest papal

visitors, Pope Vigilius (537–555), arrived on the island very soon after

Justinian’s reconquest of Sicily from the Goths: he traveled from Rome to the

Sicilian city of Catania, where he appointed priests and deacons. He then

sailed to Constantinople in order to negotiate with the emperor Justinian I (r.

527–565) and empress Theodora (500–548) about a dispute over ecclesiastical

leadership. Later, after an illness, Vigilius died in Syracuse, whence his body

was taken to Rome for burial. Vigilius obviously deemed the island useful both

as a stopover en route to the eastern Mediterranean and as a significant place

within the wider Latin Church. Other popes and their officials, throughout the

sixth through ninth centuries, likewise traveled to Sicily regularly,

demonstrating the island’s integral position in the Mediterranean system and

its role as a node of Rome-Constantinople communications.

This integration of Greek-ruled Sicily with the church in

Rome is most evident in the corpus of letters written by Gregory the Great (pope

from 590 to 604). Pope Gregory maintained continuous contact with Sicily and

left a series of letters concerning the island that serves as the most

important source of information about Sicily in the sixth century. For example,

one of Gregory’s earliest extant letters, written in 590, was sent to all of

the island’s bishops, and in it he appointed Peter as his subdeacon on the

island, in charge of administering the Sicilian patrimony on the pope’s behalf.

Throughout his letters, Gregory shows himself to have been deeply concerned

with the political, ecclesiastical, and economic affairs of the island. Also

the personal owner of extensive lands and the founder of several monasteries in

Sicily, Gregory remained, throughout his papacy, in regular contact with his

agents and with the Roman clergy on the island. He intervened often in the

affairs of the Sicilian churches, appointed and corresponded with local

bishops, founded monasteries and convents on Sicily, and kept a watchful eye on

the Greek praetors who ruled the island on behalf of Constantinople. For

example, he wrote a letter in 590 to Justin, the praetor of Sicily, in which he

noted that he would be closely observing Justin’s administration of the island.

The connection between Greek Sicily and the church at Rome

continued throughout the seventh and eighth centuries, even at the highest

level of church authority.40 In fact, several popes from those years were born

and educated on the island, some from the Latin population and some from the Greek.

Pope Agatho (r. 678–681) was originally from Sicily (natione Sicula), although

very little is known of his life there; he seems not to have maintained a

particularly close relationship with the island. Likewise born in Sicily was

Pope Leo II the Younger (682–683), who was renowned for his knowledge of both

Greek and Latin; his biographer asserts that he translated into Latin the acts

of the Third Council of Constantinople (680–681), which condemned

Monothelitism. Another seventh-century pope, Conon (686–687), was born in

Greece but was raised and educated in Sicily before he traveled to Rome and

took leadership of the Latin Church. Also raised and educated in Sicily was

Pope Sergius I (687–701), whose father, Tiberius, was of Syrian origin, having

migrated to Palermo (called at the time Panormus; see figure 2) from Antioch.

Likewise, Pope Stephen III (768–772) was born in Sicily and moved as a youth to

Rome, where he became a cleric and a monk in St. Chrysogonus’s monastery before

ascending to the papacy. Despite having been transferred to Greek political

control, Sicily was, to some significant degree, still considered part of the

Latin Church, such that the island could be the source of so many popes during

these centuries. The island may have served as a convenient source of

Greek-educated candidates during a period in which Constantinople continued to

try—increasingly unsuccessfully—to appoint and approve the election of the

popes. Sicily, with its connections to both churches, may have been an easy

place for emperors to find candidates for the papacy with enough familiarity

with the two traditions to serve the interests of both institutions.

Some of the relations between Byzantium and the leaders of

western Europe, as directed through Sicily, were more hostile. For example, the

vita of Pope John VI (r. 701–705) records that the Byzantine exarch of Italy,

Theophilactus (r. 701/702–709), traveled from Sicily to Rome for unknown

reasons and encountered there a violent reception. In Rome he was met by the

local military troops (“militia totius Italiae”), who attempted to kill him.

The pope sheltered the Byzantine official, thus demonstrating his commitment to

maintaining an amiable relationship with the Byzantine emperor, even if the

local population was less welcoming to the Greek envoy. A more detailed account

of hostile relations between Rome and Constantinople being negotiated via

Sicily concerns a confrontation that took place in 732, during the first

iconoclastic period. Pope Gregory III (731–741) sent a representative named

George to the Byzantine capital with a condemnation of Emperor Leo’s position

on iconoclasm. George failed in his mission the first time he traveled from

Rome to Constantinople, so he was sent a second time. This second attempt to

deliver the pope’s message was disrupted by George’s yearlong detention in

Sicily, and the letter never made it to Constantinople. Later, the pope tried

again to send the Byzantine emperor a condemnation of iconoclasm, this time

with Constantine the defensor. On his way to Constantinople, he passed through

Sicily where he and his party were arrested and imprisoned by Sergius, the

stratēgos of Sicily, who was acting on the emperor’s orders. Sergius

confiscated the letter and held Constantine captive for nearly a year. In this

extended episode, the Sicilian Byzantine official obstructed the ability of

Rome to communicate with Constantinople its displeasure on the divisive issue

of iconoclasm. Sicily, as a regular stopping point on Rome-to-Constantinople

journeys, was well situated to act as a regional representative of the emperor

and his policies, as well as an intermediary in the relationship between pope

and emperor—whether that enhanced or limited the actual communication between

the two parties.

Like these popes, the Frankish ruler Charlemagne also used

Sicily as a locus of political leverage with the Byzantine Empire. In this, he

appears to have been following the established pathways of East-West

communication by way of Sicily. One potential point of tension between

Charlemagne and Constantinople was the political and military opportunity the

island presented to western rulers: one could invade Sicily to claim it as his

own and thus gain a foothold in a Byzantine territory with strong connections

to Constantinople. This suggestion is not found in Latin sources, however, but

only in Greek ones: for the year 800/801, Theophanes recorded that Charlemagne

had planned a naval attack on Byzantine Sicily in order to conquer the island

for his new empire. The chronicle stated that the Frankish emperor then

abandoned this plan and decided instead to seek the hand of Empress Irene as

his wife and thus sent ambassadors to Constantinople on that mission. Even if

this story was fabricated by the Greeks in their response to Charlemagne’s

claim to be the Roman emperor, it demonstrates that they recognized the

possibility that Sicily could potentially be used as a stepping-stone between

West and East. Another example of Sicily as a locus of political conflict

between eastern and western claimants to the Roman imperial title concerns a

Byzantine official from Sicily who defected to the court of Charlemagne in the

year 800, for an unknown reason. He stayed in Charlemagne’s service for ten

years before requesting that he be sent back to Sicily. The story of this

official may reflect the competition between East and West over claims to

authority. Both of these examples, however tenuous, suggest that Sicily served,

to some western political leaders, as a nearby representative of the Byzantine

Empire and thus as a mediator of both diplomacy and potential aggression.

Charlemagne’s supposed choice between conquering the island and marrying the

empress suggests that the island could, in fact, be as much of a key to uniting

the two empires as could a marriage alliance.

Sometimes the Rome-to-Constantinople route through Sicily is

only implied in the extant sources by notifications about the transmission of

news. Several early sources relate that western leaders received important

messages from Constantinople by means of ambassadors sent to Rome by Greek

Sicilian officials, but we learn nothing else about the trips to and from

Sicily. For example, in 713 a messenger arrived in Sicily from Constantinople

and announced that Anastasius II (713–715) had deposed Philippicus (711–713)

and replaced him as emperor; this news then traveled from Sicily to Rome.

Another similar incident is found in the brief notice that in 799 Michael, the

governor of Sicily, sent a representative named Daniel to the court of

Charlemagne, although the business he was charged with conducting between

Charlemagne and Sicily’s governor is unknown. He may have been carrying news or

orders on behalf of Sicily or, like many of the other messengers found in the

sources, on behalf of Constantinople via Sicily’s Byzantine officials. It is

likely that other such travel between the two courts occurred but was not

documented, as the arrival of a Sicilian envoy to Charlemagne’s court was not

recorded as an incident out of the ordinary. Most travel by messengers is only

implied in our sources, through the record of the news that was transmitted or

by a report that envoys appeared as passengers on ships on which other

travelers were sailing. For example, there is a brief reference in a saint’s

life to both imperial and papal envoys sailing on the same ship from

Constantinople to Sicily as the holy man, but we learn nothing of the missions

on which these messengers traveled. The travels of these particular envoys are

not known from other sources, and it is likely that many other such journeys

took place but were not recorded in surviving texts.

Two letters dated November 813, written by Pope Leo III

(795–816) to Charlemagne, also provide evidence that news traveled from

Constantinople to both Rome and the Frankish imperial court via Sicily. In the

first, Leo mentions a letter sent to him on Charlemagne’s behalf by the

Sicilian stratēgos, Gregory, in response to one that the pope had delivered.

The pope’s letter conveys that the Byzantine emperor Michael (Michael I

Rangabe, r. 811–813) had entered a monastery and had been replaced on the

imperial throne. Leo explains to Charlemagne in the letter that he had learned

the news from a papal representative who had traveled from Rome to Gregory’s

court in Sicily. The second letter from Leo continues the discussion of the

events in Constantinople, bringing news about the ascension of Leo V, “the

Armenian,” (r. 813–820) to the imperial throne. These two pieces of

correspondence indicate that at times both Rome and the emperor’s court relied

on Sicilian officials for news from Constantinople and that Sicilian envoys

were accustomed to taking such news to Europe. The movement of information via

Sicily also suggests that travel both between Constantinople and Sicily and

between Sicily and Rome was routine: Sicily stayed regularly connected to both

the Greek and Latin Christian worlds, simultaneously sending messengers to and

receiving them from multiple places.

On the other hand, some accounts of communications between

Constantinople and Rome highlight the fact that Sicily was not the only route

by which information or envoys traveled between Constantinople and the West. In

797, the emissary Theoctistos, sent by Nicetas, the stratēgos of Sicily,

arrived at Aachen with a letter for Charlemagne from an emperor (Constantine

VI, r. 780–797) who had in the meantime been deposed in Constantinople (by his

mother, Empress Irene, r. 797–802). That vital piece of information had already

reached Aachen by another route before the Sicilian messenger arrived, making

the deposed emperor’s message obsolete before it even arrived at Aachen. This

anecdote shows that the overland route was sometimes faster than the sea route

through Sicily. This, then, suggests that Sicily acted as a significant node in

the communication linkage between Rome, the Frankish court, and Constantinople

not simply for its geographical expedience but for other reasons as well.

Indeed, if messages could reach Rome or Aachen more quickly by routes not

involving Sicily, then the utilization of the island as a stopover in other

instances must have been related to other factors, such as the perceived

reliability of particular Sicilian officials or the ease of finding passage to

the island’s ports from the eastern Mediterranean. The use of Sicily as a

transit point reflected official needs and communication patterns, not simply

the necessity to transmit information in the fastest way possible, meaning that

in certain instances Sicily could serve as a proxy for imperial authority

within the western Mediterranean and a point of connection between East and

West. At the edge of the empire, Sicily was also a useful mediator of the

relationships between Byzantium and the societies at its borders.