When the Carthaginian had spoken thus, Kaiso replied:

`This is what we Romans are like . . . [W]ith those who make war on us we agree

to fight on their terms, and when it comes to foreign practices we surpass

those who have long been used to them. For the Tyrrhenians used to make war on

us with bronze shields and fighting in phalanx formation, not in maniples; and

we, changing our armament and replacing it with theirs, organised our forces

against them, and contending thus against men who had long been accustomed to

phalanx battles we were victorious. Similarly the Samnite shield was not part

of our national equipment, nor did we have javelins, but fought with rounds

shields and spears; nor were we strong in cavalry, but all or nearly all of

Rome’s strength lay in infantry. But when we found ourselves at war with the

Samnites we armed ourselves with their oblong shields and javelins, and fought

against them on horseback, and by copying foreign arms we became masters of

those who thought so highly of themselves. Ineditum Vaticanum, ed. H. von

Arnim, “Ineditum Vaticanum,” Hermes 27 (1892): 118-30 (= Jacoby

FGrHist 839 F. 1), 3, in Cornell’s translation, Beginnings of Rome (n. 1), 170.

Cf. Diod., 23.2.1; Ath. 6.273 e-f; Sall. Cat. 51.37-38.

Map showing expansion of

Roman sphere of influence from the Latin War (340–338 BC) to the defeat of the

Insubres (222 BC).

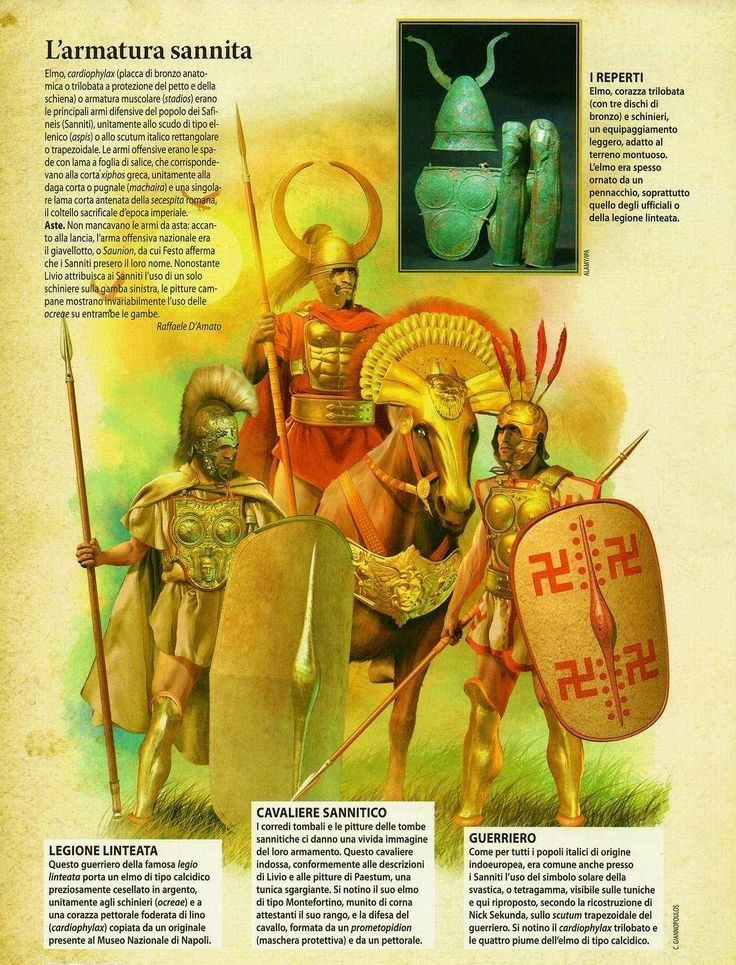

The Samnites were the archetypal warriors of the ver sacrum

(Sacred Spring). Claiming descent from the Sabines (hence the Samnites and

other Oscan speakers were known as Sabelli or Sabellians) they believed that a

bull sent by Mamers guided them to their homeland in the southern central

Apennines. They divided into four tribes, the Pentri, Caudini, Caraceni and

Hirpini. The latter took their name from Mamers’ hirpus (wolf), which they

followed in a subsequent ver sacrum. The four tribes cooperated in a military

alliance.

They fought long and hard against the Romans in a series of

wars from 343 BC to 272 BC, and were the only Italian nation whose military

qualities the Romans feared. According to Livy they were warlike, brave and

resolute even in adversity. Their main strength was in swift moving

javelin-armed infantry, organised in cohorts and legions. Many of them being

armoured. Their preferred tactic was to surround an enemy and pelt him with

javelins while avoiding hand-to-hand contact. If possible they would ambush the

enemy rather than risk a pitched battle. The wooded hills of their home

territory were ideally suited to such tactics. However, they were prepared to

fight it out in the open if necessary.

In 354 BC the Samnite League sent an embassy to Rome,

requesting friendship and alliance between their peoples. According to Livy,

the Samnites were prompted to do so because they were impressed by a Roman

victory over Tarquinii, but Rome’s reduction of the Hernici in 358 BC would

have been of more interest to the Samnites; the victory over Tarquinii merely

reinforced the growing reputation of Roman military prowess. However, the

allies fell out in 343 BC when the Samnites attempted to expand west into

northern Campania and the territory of the Sidicini, and Capua, the leading

Campanian city-state, appealed to Rome for help against the invaders. The

Romans scented an opportunity to massively expand their little empire and

renounced the treaty with the Samnite League.

The Romans sent priests called fetiales to the border of

Samnium, perhaps in the vicinity of Sora, where the chief fetial declared war

by symbolically casting a spear into the territory of the enemy. The consul

Valerius the Raven (Corvus) was assigned the war in Campania, while his

colleague Cornelius the Greasy (Arvina) invaded Samnium. The Raven pushed south

to Mount Gaurus, in the hills above Puteoli, drawing the Samnite army away from

Capua. The Samnites were defeated after a long struggle, requiring the heroic

Valerius to dismount from his horse and lead a counter-attack on foot, and they

withdrew from Campania.

Meanwhile, Cornelius the Greasy had advanced into the

territory of the Caudini located immediately east of Capua. In the vicinity of

Saticula his army was trapped in a heavily wooded defile; this was a favourite

tactic of the Samnite mountain men. However, Cornelius’ army was extricated by

a military tribune, Publius Decius Mus. Tradition asserted that before the

Samnites completed the encirclement and closed in, the military tribune led the

hastati and principes of the consular legion (2,400 legionaries) through the

woodland to a hill above the enemy; distracted by Mus’ sudden appearance on the

hill, the rest of the consul’s army was able to escape. The dauntless Decius

was now surrounded by the full Samnite army (apparently numbering in excess of

30,000 warriors), but during the night the tribune led his legionaries down the

hill, broke through the encirclement and reunited with the consul’s army. In

the morning the Samnites, still disorganized from the confusion resulting from

Decius’ escape, were surprised by the Romans and soundly defeated. Decius was

where the fighting was thickest, claiming that he had been inspired by a dream

in which he achieved immortal fame by dying gloriously in battle. It has been

suggested that Decius’ peculiar cognomen, Mus, meaning ‘rat’, derived from his

exploits at Saticula, perhaps because he dared to fight at night, a most

unusual enterprise for a Roman commander.

Despite these two heavy defeats the Samnite League was not

ready to throw in the towel. A new army of 40,000 men (another exaggeration of

the later Roman sources) was raised from the populous tribes of Samnium, and it

established a camp by Suessula, a city on the eastern edge of the Campanian

plain. The army of Cornelius Arvina had evidently withdrawn from the territory

of the Caudini, and it fell to the Raven to fight this last battle of the

campaign. He marched from his camp at Mount Gaurus and overcame this new

Samnite army as well. Suessula was located at the mouth of a valley that led to

the Caudine Forks, an important pass into western Samnium. The defeated

Samnites presumably retreated by way of the Forks into the country of the

Caudini and Hirpini and thence to their homes, but the Raven did not follow. He

was sensible not to. The Suessulans may have informed him that the pass was the

perfect spot to trap an army and he had no desire to repeat the error of his

colleague.

The consuls returned to Rome to celebrate triumphs (21 and

22 September 343 BC) and news of their victories spread quickly across Italy.

The Faliscans were prompted to seek a formal treaty of friendship and alliance

(foedus) with their old enemy, perhaps fearing that if they simply maintained

the forty years’ truce imposed on them in 351 BC, the bellicose Romans would

find an excuse to declare war and seize their territory. The news also

travelled overseas. Ambassadors from Carthage arrived in Rome, keen to bolster

the alliance of 348 BC, full of congratulations for the victories over the

Samnites and bearing the not inconsiderable gift of a gold crown weighing 25

pounds. However, the war was not over and substantial Roman garrisons were

installed in Capua and Suessula to protect them from Samnite incursions.

In 342 BC the Samnites nursed their wounds. The scale of

their defeats could not have been as great as Livy’s account suggests, but the

Romans had administered a serious blow to their military prestige and

confidence. Samnite manpower in 225 BC (by which time their territory was very

much reduced) is reported by the reliable Polybius as 70,000 infantry and 7,000

cavalry. Afzelius and Cornell have estimated the population of Samnium in the

middle of the fourth century BC at around 450,000 persons, and the report of

the geographer Strabo that the Samnites had 80,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry

may belong to this period. Strabo’s manpower figures would represent somewhat

less than 20 per cent of the estimated population. The total number of adult

males, including seniores, would have been well in excess of 100,000, but these

figures are misleading and should be regarded as potential reserves of manpower

rather than the number of warriors the Samnite League could mobilize at one

time. If the Samnites had lost 30,000 men at Saticula and suffered similarly

enormous casualties at Mount Gaurus and Suessula, as Livy’s accounts suggest,

then their military power would have been utterly broken and their rural

economies, which required men to tend crops and herds, would have collapsed.

The strengths of the consuls’ armies are not attested. It is uncertain if the practice of enrolling two legions per consular army was yet in effect. It is generally believed that the regular strength of a consular army was raised from one to two legions in 311 BC. However, because the Romans could not draw on any substantial Latin manpower in the 340s BC, it may be that extra consular legions were raised. Campanian levies would have bolstered the Roman legions, and the aristocratic cavalrymen of Capua and the other cities were famed for their martial prowess. The number of soldiers in a consular army may be estimated at 9,000 – 18,000, that is one or two legions of c. 4,500 (4,200 infantry plus 300 cavalry) and an equal number of Campanians. The Samnite armies were probably of similar size.