Whatever might be the Reich’s advantages on the levels of

policy and strategy, the approximately 130 German infantry divisions in

Barbarossa’s order of battle carried weapons looted from a half dozen armies.

There were five divisions of Waffen SS, with greater reputations for ferocity

than fighting power. Client states—Romania, Finland, Slovakia—provided between

20 and 30 more divisions of limited operational value. Occupied Europe was

stripped of everything with four wheels and an engine to provide logistic

support for this mixed bag. Trucks were purchased from Switzerland. Other

trucks were requisitioned from French North Africa. And in the final analysis,

sustaining the invasion still depended heavily on captured railroads whose

track gauge had to be altered to fit Western rolling stock.

Traditional logistics were just the tip of an iceberg of

improvisation. The army expected to sustain itself directly from the campaign’s

beginning by utilizing captured Red Army resources and systematically

exploiting the civil population. Whatever the military merits of this approach

for foot- marching, horse-powered formations, its applicability to the

mechanized troops was marginal. To cite only the most obvious example, German

tanks had gasoline engines. In the West they had been able to refuel from local

filling stations. In Russia such facilities were limited, and Russian gas was

of sufficiently lower octane to be a positive risk for already overworked

motors. If anything at all went wrong, solutions would have to be improvised.

Meanwhile, the theater-level planning for Barbarossa virtually guaranteed

problems.

Hitler based Operation Barbarossa on the assumption that

success depended on shattering the USSR in one blow. His directive of December

18, 1940, could not have been plainer: the bulk of Russian forces in the west

was to be destroyed in a series of bold operations. The generals concurred.

They never proposed to match the Russians face-to-face, gun-for-gun, and

tank-for-tank. Mechanized war depended on timing: a dozen tanks on the spot

were preferable to 50 an hour later. Mechanized war depended on disruption:

confusion produced entropy while discouraging resistance. And mechanized war

depended on hardness. An enemy could not merely drop his weapon and raise his

hands. He needed to feel defeat in his ductless glands—and in his soul. The

close synergy between Nazi principles and military behavior demonstrated from

the beginning of the Russo-German War was not entirely a consequence of shared

racist values. It reflected as well the “way of war” the German army had been

developing since at least 1918.

How best then to break the enemy comprehensively? The first

operational study began in July 1940. It projected a dual strike, one directly

on Moscow, the other on Kiev. This should be enough to destroy the Red Army and

disrupt the Soviet state. The ultimate objective was a line:

Rostov-Gorki-Archangel; anything to the east would remain “Indian country”

until further notice. A parallel study projected three simultaneous assaults,

toward Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev. From the beginning, in other words, long

before Hitler’s direct involvement, the army’s plans incorporated dispersion of

the army’s striking power.

This was not a manifestation of ignorance, willful or

otherwise. German planners were fully aware of the size of the Soviet Union.

They had reasonable ideas of the kinds of changes it might impose on an

operational approach designed for application against small countries. Attaché

reports and clandestine reconnaissance flights provided information both

negative (on such issues as the lack of roads appropriate for rapid movement)

and positive (indicating significant recent buildup of industrial capacity on

both sides of the Urals). A series of map exercises in early December 1940

indicated significant problems of overstretch, producing results much like

those of a similar exercise in 1913: German forces hung up in the middle of

Russia as the enemy massed for a general counteroffensive. The conclusion was

that German forces were barely sufficient for the assigned mission. And that

was at the beginning.

Germany’s overall mobilization might have been incomplete,

but by the summer of 1941, 85 percent of men between 20 and 30 were serving in

the Wehrmacht. The remainder were considered indispensable to the war economy.

In May, Halder informed the Replacement Army that the initial battles would

cost 275,000 casualties, with another 200,000 expected in September. The

available replacement pool for the army was 385,000. Simple arithmetic

indicated that the pool would be empty before autumn even given Halder’s

optimistic time frame.

Shortfalls were certain in another crucial area. The success

of mobile war as practiced in Germany depended heavily on air support in a

context of air superiority. The planes need not always be present, but they had

to be available. The Luftwaffe had exponentially more experience than the Red

Air Force, along with significantly superior aircraft and tactics. The

Luftwaffe was also fighting in the West and the Mediterranean, suffering steady

attrition of planes and crews. It would be covering a far greater geographic

area than in 1940, with corresponding extension of technical and logistical

demands. Even in a short campaign, the ground forces were correspondingly

likely to be depending on their own skills and resources a higher proportion of

the time than ever before.

Planning for Barbarossa rolled on, moving from conceptions

into details without a bump. Private reservations, expressed in such

passive-aggressive ways as buying and reading Baron Caulaincourt’s memoirs of

Napoleon’s disastrous 1812 campaign, did not prevent participation of the

middle-ranking officers who would be the field commanders. What emerged,

significantly independent of Hitler’s direct involvement, was a sophisticated

version of what was essentially a military steeple-chase: three army groups

lined up on the frontier, and at the starter’s barrage, going as fast as

possible in three extrinsic directions. Instead of the single clenched fist of

Frederick the Great, or the elder Moltke’s “moving separately and fighting

together,” the projected operation resembled a martial artist spreading his

fingers as he struck what was intended as a killing blow. Instead of being

structured into a decisive point, soldiers, cities, and resources shifted

priorities in an ever-changing kaleidoscope. The closest thing to

prioritization was Hitler’s emendation of the army’s original plan to provide

for Leningrad’s capture before mounting a decisive attack on Moscow. And all

this was to be achieved on a campaign of four or five months’ duration.

Scholars and soldiers increasingly, one might say

overwhelmingly, describe Barbarossa as fundamentally flawed, a program for

defeat even in a narrow military context. But while its dysfunctional genesis

may have been in the fever swamps of hubris and racism, a steel thread linked

Barbarossa to the real world: the panzers. The Führer and his generals were

convinced that the army of the Third Reich had developed a style of war not

merely countering the historic Russian strengths of mass, space, and

determination, but rendering them irrelevant: a heavyweight boxer confronting a

sawed-off shotgun. In his December directive Hitler emphasized “bold armored

thrusts.” The army’s map exercises concluded that mobile units would decide the

campaign and the war. At every turn the structure of Barbarossa was an inverted

pyramid, with the panzers at the tip. Va banque, all or nothing—the Reich’s

fate rode with the tanks.

Barbarossa Commences

The barrage opened with Teutonic precision at 3:30 AM on

June 22, 1941. A half hour earlier, Luftwaffe bombers had crossed into Russia

to strike major air bases. Earlier still, special operations detachments had

infiltrated Russian territory, setting ambushes and seizing bridges. As dawn

broke, three million men crashed forward under an umbrella of more than a

thousand planes.

The Russians were taken completely by surprise at all

levels. A train carrying Russian goods had crossed into Germany shortly after

midnight. One unit of the Red Army reported it was under attack only to receive

the response, “You must be insane!” Stalin suffered a nervous collapse. Foreign

minister Vyacheslav Molotov confronted the German ambassador: “Surely we have

not deserved this!”

Martin van Creveld’s careful calculations have long since

discredited the long-standing argument that the Balkan operation delayed

Barbarossa by a significant amount of time—enough, perhaps, to set up the

Germans’ eventual defeat by “General Winter.” Instead the unexpectedly rapid

collapse of Yugoslavia made it possible to transfer and refit the mobile

divisions ahead of the originally projected schedule. The reason their

transport was not expedited was the slow arrival of the motor vehicles for the

panzers’ rear echelons. There was no point in rushing movements from the

Balkans when trucks and related equipment were still arriving at what Halder

called the last moment: the end of May and early June. Drivers and unit

mechanics had scant time to get acquainted with their vehicles’ quirks even had

they nothing else to do—an unlikely circumstance in the context of the great

invasion.

Spring also came late to western Russia in 1941. Thaws were

heavy; streams and rivers overflowed; ground was soft. Here was a case when

losing time in the short run meant saving it in the long run—especially given

the ramshackle nature of the mobile divisions’ supply columns.

The scale of Barbarossa and the subsequent operations of the

Russo-German War preclude continuing at the level of detail presented earlier

in the text. It is correspondingly useful to begin with a scorecard. Wilhelm

Ritter von Leeb’s Army Group North included Panzer Group 4. Erich Hoepner had

three panzer and three motorized divisions, with two corps headquarters. One

was commanded by Erich von Manstein. Restored to favor, in the coming weeks

Manstein would emerge as a rising star of the armored force. Bock’s Army Group

Center had two panzer groups. Number 3, under Hermann Hoth, had three panzer

and three motorized divisions. Panzer Group 2 was Heinz Guderian’s: five panzer

and three motorized divisions, plus Grossdeutschland. Guderian was also

assigned the army’s only horse cavalry division—an apparent contradiction in

technological terms that reflected the potential threat from the waterlogged

Pripet Marshes on his flank. Rundstedt commanded Army Group South, with five

panzer and three motorized divisions along with the Leibstandarte, all under

Kleist’s Panzer Group 1.

As in France, the command relationships between panzer

groups and field armies were left ambiguous—a situation that would contribute

significantly to friction and ill- will as Barbarossa developed. In contrast to

1940, however, each group was assigned a number of infantry divisions: two for Hoepner,

three for Hoth, no fewer than six each for Guderian and Kleist. As early as

February, Hoth protested that the infantry would slow his advance and block the

roads for the panzers’ rear echelons. Bock and Guderian were unhappy for

similar reasons. Bock’s comment that his superiors did not seem to know what

they wanted reflected Halder’s ongoing concern about the mobile formations

getting too far ahead of the marching masses. But in 1941, Guderian commanded

more infantry than panzer divisions, and had fewer tanks than in the previous

year. In 1940 his corps frontages rarely exceeded 15 miles; in Russia, the norm

for his group would be 80 and more. Precisely how the infantry was supposed to

cope remained unaddressed.

The generally accepted rule of thumb is that an attack needs

a local advantage of three to one in combat power to break through at a

specific point—assuming rough equality in “fighting power.” On June 22,

tactical surprise produced a degree of operational shock denying conventional

wisdom. The Red Air Force lost almost 4,000 planes in the war’s first five

days—most of them destroyed on the ground. Other material losses were

proportional. Command and control at all levels seemed to disintegrate. The

Germans were nevertheless encountering not an obliging enemy, but one caught

between two stools. The impact of Stalin’s purges on the officer corps has

recently been called into question on the basis of statistics indicating that

fewer than 10 percent were actually removed. The focus on numbers overlooks the

ripple effects, in particular the diminishing of the mutual rapport and

confidence so important in the kind of war the Germans brought with them.

At the same time, in response to substandard performances in

Poland and Finland, the Red Army had restored a spectrum of behaviors and

institutions abolished after the revolution of 1917, designed collectively to

introduce more conventional discipline and reestablish the authority of

officers and senior NCOs. These changes did not sit well with a rank and file

appropriately described as “reluctant soldiers.” Nor did they fit well on

officers who were themselves profoundly uncertain of their positions in the

wake of the purges..

One result was a significant decline in training standards

that were already mediocre. Western images are largely shaped by German myths

describing the Russian as a “natural fighter,” whose instincts and way of life

made him one with nature and inured him to hardship in ways foreign to “civilized”

men. The Red Army soldier did come from a society and a system whose hardness

and brutality prefigured and replicated military life. Stalin’s Soviet Union

was a society organized for violence, with a steady erosion of distinctions and

barriers between military and civilian spheres. If armed struggle never became

the end in itself that it was for fascism, Soviet culture was nevertheless

comprehensively militarized in preparation for a future revolutionary

apocalypse. Soviet political language was structured around military phrasing.

Absolute political control and comprehensive iron discipline, often gruesomely

enforced, helped bridge the still- inevitable gaps between peace and war.

The winter campaign in Finland during 1939-40 had shown that

Russian soldiers adapted to terrain and weather, remained committed to winning

the war even in defeat, and maintained discipline at unit levels under extreme

stress. But a combination of institutional disruptions and prewar expansion

left too many of them ignorant of minor tactics and fire discipline—all the

things the German system inculcated in its conscripts from the beginning. The

Rotarmisten, the Red soldiers, would fight—but too often did not know how to

fight the Germans.

The quality of Soviet tanks in the summer of 1941 has often

been misrepresented. The Red Army fielded about 24,000 of them on June 22,

1941. More than 20,000 dated from the mid-1930s. The major types were the T-26

infantry tank, 9.5 tons with either a 37mm or a 45mm antitank gun; and the BT-7

“fast tank,” a 14-ton Christie model with a 45mm gun whose road speed of 45

miles per hour had been bought at the expense of armor protection. Frequently

and legitimately described as obsolescent, these tanks were nevertheless a

reasonable match for anything in the German inventory, one for one, on anything

like a level field.

The Red Army’s institutional behavior prior to Barbarossa

could not have been less suited to providing that level field had it been

designed by the Wehrmacht. Since the 1920s the USSR had been developing

sophisticated concepts of mobile armored warfare, and using the full resources

of a command economy to produce appropriate equipment. By 1938 the Soviet order

of battle included four tank corps and a large number of tank brigades whose

use in war was structured by a comprehensive doctrine of “deep battle” that

included using “shock armies” to break through on narrow fronts and

air-supported mobile groups taking the fight into the enemy’s rear at a rate of

25 or 30 miles a day. But in November 1939 these formations were disbanded,

replaced by motorized divisions and tank brigades designed essentially for

close infantry support.

One reason for this measure—the public one—was that the

Spanish Civil War had shown the relative vulnerability of tanks, while large

armored formations had proved difficult to control both against the Japanese in

Mongolia and during the occupation of eastern Poland. Reinforcing operational

experience were purges that focused heavily on the armored forces as a potential

domestic threat. Not only were the top-level advocates of mobile war

eliminated, including men like Mikhail Tukhachevsky; all but one commander at

brigade level and 80 percent of the battalion commanders were replaced—and many

of those they had replaced had succeeded men purged earlier.

German successes in 1940 combined with the running down of

the purges to encourage reappraisal already inspired by the Red Army’s dubious

performance in Finland. Beginning in 1940 the People’s Commissariat of Defense

began authorizing what became a total of 29 mechanized corps, each with two

tank divisions and a motorized division: 36,000 men and 1,000 tanks each, plus

20 more brigades of 300 T-26s for infantry support! The numbers are

mind-boggling even by subsequent standards. Given the Soviets’ intention to

equip the new corps with state-of-the-art T-34s and KV-1s, the prospect is even

more impressive. Reality was tempered, however, by the limited number of the

new tanks in service—1,500 in June 1941—and tempered even further by

maintenance statistics showing that 30 percent of the tanks actually assigned

to units required major overhauls, while no fewer than 44 percent needed

complete rebuilding.

That left a total of around 7,000 “runners” to face the

panzer onslaught. It might have been enough except for, ironically, a command

decision that played directly into the Soviet armored force’s major weaknesses.

Recently available archival evidence shows that, far from collapsing in

disorganized panic, from Barbarossa’s beginning the Red Army conducted a

spectrum of counterattacks in a coherent attempt to implement prewar plans for

an active defense ending in a decisive counteroffensive. The problem was that

the mechanized corps central to these operations were too cumbersome to be

handled effectively by inexperienced commanders, especially given their barely

adequate communication systems. Their efforts were too often so poorly

coordinated that the Germans processed and described them as the random

thrashings of a disintegrating army. Most of the prewar Soviet armored force,

and more than 10,000 tanks, were destroyed in less than six weeks.

Yet even in these early stages the panzers were bleeding.

War diaries and letters home described “tough, devious, and deceitful” Russians

fighting hard and holding on to the death. What amounted to a partisan war

waged by regular soldiers was erupting behind a front line at best poorly

defined. Forests and grain fields provided favorable opportunities for

ambushes. Isolated tanks could do damage before they were themselves destroyed.

Casualties among junior officers, the ones responsible for resolving tactical

emergencies, mounted as the Germans found themselves waging a 360-degree war.

In Poland and France, terrain and climate had favored the

panzers. From Barbarossa’s beginnings they were on the other side. Russian road

conditions were universally described as “catastrophic” and “impossible.” Not

only impressed civilian vehicles but army trucks sacrificed suspensions,

transmissions, and oil pans in going so makeshift that armored cars balanced

precariously on the deep ruts. Russian dust, especially the fine dust of sandy

Byelorussia, clogged air filters and increased oil consumption until overworked

engines gave in and seized up. Personal weapons required such constant cleaning

that Soviet hardware, especially the jam-defying submachine guns, unofficially

began replacing Mausers and Schmeissers in the rifle companies.

The earlier major campaigns had lines of communication short

enough to return seriously damaged tanks to Germany. Divisions needed to

undertake no more than field repairs. Russian conditions demanded more, and

maintenance units proved unequal to the task. Not only was heavy equipment for

moving disabled vehicles unavailable; workshops began running short on

replacement parts almost immediately. Too often the result was a tank

cannibalized for spares, or blown up before being abandoned.

Then conditions worsened. By early July episodic storms

became heavy rains that turned dirt roads to bottomless mud and made apparently

open fields impassable morasses. A first wave of vehicles might get through,

but attempts at systematic follow-up usually resulted in traffic jams regularly

described in words like “colossal.” Dust and mud combined to make fuel

consumption exponentially higher than standard rates of usage. Empty fuel tanks

as well as breakdowns began immobilizing the panzers. Though figures vary

widely, the histories and records of the panzer divisions in Army Groups South

and Center present rates of attrition eroding combat-effective strengths to

levels as low as 30 or 40 percent. Even small-scale Russian successes—three

tanks knocked out here, a half dozen there; one searing encounter that left 3rd

Panzer Division 22 tanks weaker in just a few minutes—had disproportionate

effects on diminishing numbers.

Vehicle losses were only part of the panzers’ problem, and

arguably the lesser part. Effectiveness decreased as men grew tired and made

the mistakes of fatigue, ranging from not checking an engine filter to not

noticing a potential ambush site. Infantrymen constrained to leave their trucks

to make corduroy roads from tree trunks, motorcyclists choked with dust that

defied kerchiefs soaked with suddenly scarce water, and tankers trying to

extract their vehicles from mudholes that seemed to appear from nowhere were a

long way from blitzkrieg’s glory days. There were still plenty of volunteers

for high-risk missions. But by its third week Barbarossa had already cost more

lives than the entire campaign in the West. And Moscow was a long way off.

With supply columns increasingly vulnerable to ambushes and

concentrating on bringing up material, the panzer troopers helped themselves to

what was available. Stress and fatigue synergized with ideologically structured

racism to underpin behavior that from the beginning caused levels of bitterness

noticed even in German official reports. It usually began by “requisitioning”

food: portable items like chickens, eggs, fruit, and milk; stores of grain;

cattle and hogs for impromptu butchering. Looting was regularly accompanied by

destruction, and the effect on the victims was compounded by personalized

meanness: smashing dishes, ripping up clothes and bedding, using boots and

rifle butts in place of words and gestures.

The Germans as well found themselves facing “colossal” tanks

against which German panzers and antitank guns seemed to have no effect. The

T-34 disputes the title of the war’s best tank only with the German Panther.

Its design, featuring sloped armor, a dual-purpose 76mm gun, and a diesel

engine and Christie-type suspension allowing speeds up to 35 miles per hour,

set standards in the three essentials of protection, firepower, and mobility.

Germans sometimes confused the T-34 with the BT-7. Few made that mistake a

second time. Distributed in small numbers and manned by poorly trained crews,

from Barbarossa’s beginnings not only did the T-34 prove impervious to German

armor-piercing rounds at fifty feet and less; it ran rings around Panzer IIIs

and IVs used to dominating in speed and maneuverability.

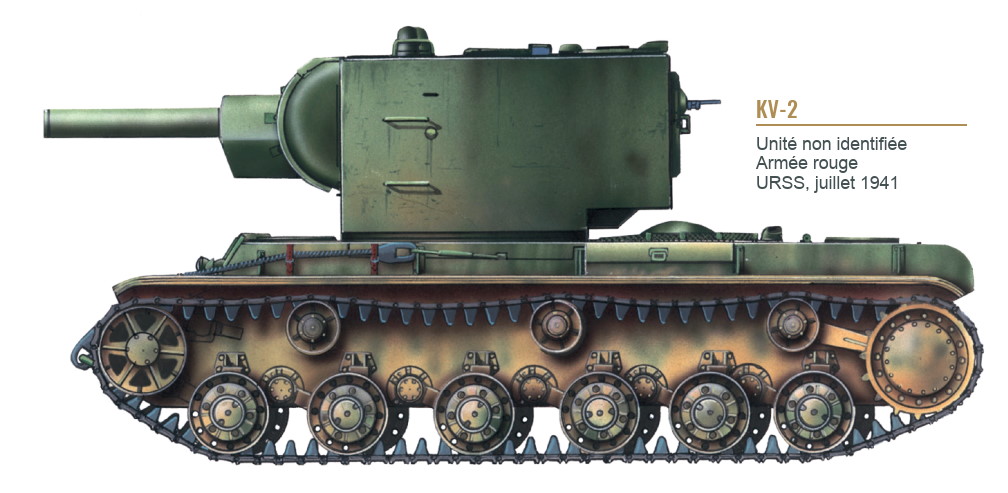

More frightening, because it could not be mistaken for

anything else, was the KV-I. At 43 tons, it was undergunned with a 76mm piece.

It was mechanically troublesome and not particularly maneuverable. But with

armor up to four inches thick, the KV did not have to move very often. Panzer

Group 4 initially found the dense northern forest a greater obstacle than the

Russian army. Manstein’s new LXVI Panzer Corps covered almost 100 miles in four

days, crossing Lithuania in a knife-thrust that carried it into Daugavpils and

across the vital Dvina River bridges. The course for Leningrad seemed well set.

Then the KVs made an appearance. The 37mm guns were useless. Mark IV rounds

made no impression from front or sides. Six-inch howitzer shells burst

harmlessly on the plating. One KV rolled right over a bogged-down 35(t),

crushing it like a tin can. Another, in an often-told vignette, held up the

entire 6th Panzer Division of Georg-Hans Reinhardt’s XLIV Panzer Corps for two

days, blocking a key crossroads, defying even 88mm rounds until, in an attack

coordinated by a full colonel, pioneers were able to shove grenades into the

turret.

Initially Leeb gave Hoepner a free hand. His group remained

unattached to either of the armies and was allowed to make its own way forward.

But more and more KVs appeared in the van of Soviet counterattacks. Sixth

Panzer Division’s 35(t)s engaged them at 30 yards. They overran the 114th

Motorized Regiment, leaving in their wake a trail of crushed and mutilated

bodies that sparked and fueled stories of unprovoked massacre. First Panzer

Division’s command post was caught so badly by surprise that the staff and

commander used their pistols. The roads, few, narrow, and unpaved, had a way of

disappearing entirely. Closely flanked by forests and swamps, they channeled

and constrained German movement and were ambush magnets even for demoralized

stragglers. Tanks, trucks, and half-tracks lurched from village to village as

bemused officers discarded useless maps and sought directions from local civilians

who offered only blank stares and shrugged shoulders.

Nor could towns be bypassed readily. Clearing them took time

and lives. As the panzers approached Pskov their purportedly supporting

infantry was mopping up in Daugavpils, 60 miles to the rear. Leeb’s repeated

reaction was to halt the armor despite vehement objections from Hoepner and his

corps commanders that operations were being sacrificed to tactics. And

Leningrad seemed ever farther away.

In contrast to Leeb’s sector, Army Group South had ample

open ground in front of it. Rundstedt used his infantry to make the initial

breakthrough on a 50-mile front, and by the morning of June 23 the Landser were

past the frontier positions. Breakout was another matter. The commander of the

Southwestern Front (the Soviet counterpart of a German army group), Colonel

General M. P. Kirponos, had four infantry armies and six mechanized corps under

his hand, and understood how to use them. Panzer Group 1 met resistance

featuring large-scale counterattacks better organized, and fighting withdrawals

more timely, than those facing its counterparts. Not until early July would the

panzer spearheads crack Soviet defenses and erode Soviet command and control to

a point where one can speak of systematic maneuver operations beginning. Even

then Soviet attacks regularly threw the Germans off balance.

Army Group Center’s sector is usually referenced as the site

of Barbarossa’s greatest initial success. Panzer Groups 2 and 3 drove so deeply

into the Soviet rear on each side of the fortress of Bialystok that on Day 2 of

the offensive, Halder spoke of achieving complete operational freedom. On June

28, Hoth’s and Guderian’s spearheads linked up at Minsk in history’s greatest

battle of encirclement. The Germans claimed 5,000 tanks and 10,000 guns

destroyed or captured. A third of a million Russians were dead or wounded;

another third of a million were on their way to German POW camps.

Seen from the sharp end, the situation was less spectacular

and less tidy. The mobile forces so far outpaced the marching divisions that

the “pocket” was in many places no more than a line on a headquarters map. Red

Army units might have been cut off but they neither surrendered nor dissolved.

“Worse than Verdun,” grimly noted one infantry colonel. Russian soldiers

filtered through and broke through the purported encirclement in numbers that

set German generals quarreling. Guderian and Gunther von Kluge, commanding 4th

Army in Guderian’s wake, reprised the earlier debate in France by disagreeing

over whether it was best advised to seal the Minsk pocket tightly or continue

driving along the high road to Moscow. Bock and Halder could see the advantages

of both prospects too clearly to decide on either.

The High Command’s decision to make another army headquarters

responsible for clearing the pocket and put Kluge temporarily in command of

both panzer groups (and confusingly retitled his command 4th Panzer Army for

that period) has been interpreted as simplifying the command structure, and as

braking the overaggressive panzers. Both were Band-Aids that did nothing to

resolve the fundamental issue of overstretch. What they did was signal a level

of indecision that encouraged Hitler to extend his direct involvement with

operational issues.

To a degree the generals’ behavior in these critical weeks

reflected the ambiguities of the matrix established 70 years earlier by Helmuth

von Moltke. While he stressed the importance of realizing that “no plan

survives first contact with the enemy,” he also asserted that the original plan

needed to be good enough to allow improvisations within its overall framework.

What held this dialectic together were the nineteenth century’s limitations on

mobility and shock. Subordinate formations—armies and corps—lacked the fighting

power to achieve decisions separately, but could not usually move far enough

away from each other to create real risks—at least when properly commanded.

The internal combustion engine and the radio had changed

those parameters—but to what degree? When exactly did the “artistic” daring and

initiative postulated by the “German way of war” cross the line into chaotic

solipsism? Or had that question lost its relevance to war-making through what

would later be called a paradigm shift?

The bones of contention, or perhaps the pawns on the board,

were the panzer and motorized divisions, consistently and haphazardly shifted

among higher commands, now as fire brigades cleaning up the rear, now as

spearheads restoring momentum at the front—and always eroding their fighting

power. But the panzer generals understood better than their more conventional

superiors that the battles of the frontier were no more an end in themselves

than their predecessors in 1914 had been. They understood as well, albeit more

viscerally than cerebrally, the volcano’s rim on which the campaign was

dancing. No matter the initial victories’ costs and successes, they were the

first stages of a campaign whose outcome depended on the armored force

maintaining its cohesion, its mobility, and its focus. Intelligence was

reporting new Soviet forces occupying positions on the road to Moscow. The

schoolboy wisdom of running faster to restore balance after stumbling seemed

all too applicable.