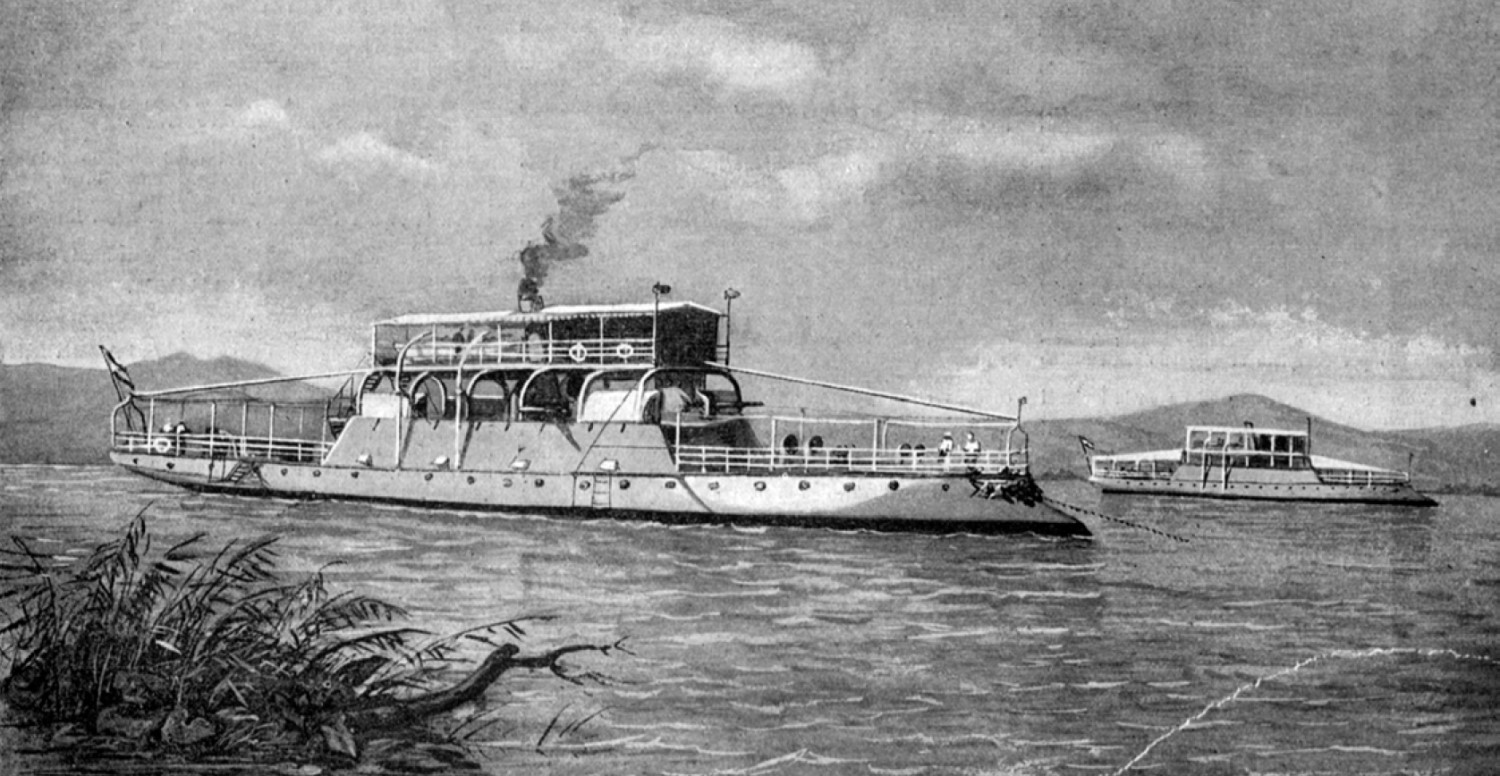

Gunboats “General Blanco” and

“Lanao”

Gunboat “General Blanco”

Gunboat General Blanco. Midsection cross-section frame

(drawn by one of the crew)

The Spanish Empire, once the greatest in the world, largely

disappeared during the Napoleonic era, leaving only a few colonies in Africa

(Morocco), the West Indies (Puerto Rico and Cuba), and the Pacific Ocean (the

Philippines and smaller island groups, among them the Carolines and Marianas).

During the latter years of the 19th century, anticolonial movements emerged in

the most important of Spain’s possessions, the Philippines and Cuba. Spain’s

Restoration Monarchy, which had been established in 1875, decided to put down

these insurgencies rather than grant either autonomy or independence. The

Spanish Army crushed the first outbreaks, the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878) in

Cuba, and the First Philippine Insurgency (1896-1897).

Spain attempted to gain support from the great powers of Europe

but failed to do so. The nation had no international ties of importance, having

followed a policy of isolation from other nations during many years of internal

political challenges, notably the agitation of Carlists, Basques, Catalonians,

and other groups. Wide- spread domestic unrest raised fears of revolution and

the fall of the Restoration Monarchy. Given these domestic challenges, Spain

did not involve itself in external affairs. The European powers, preoccupied

with great issues of their own including difficulties with their own empires,

refused to help Spain, having no obligations and no desire to earn the enmity

of the United States. Bereft of European support, Spain had to fight alone

against a formidable enemy.

Popular emotions influenced the Madrid government to some

extent; many Spaniards believed that the empire had been God’s gift as a reward

for the expulsion of the Moors from Europe and believed that no Spanish

government could surrender the remaining colonies without dishonoring the

nation. War seemed a lesser evil than looming domestic tumult.

GENERAL BLANCO Class gunboats

These steel-hulled vessels were built in 1895-96 at Cavite

for service in the Philippines against the insurgents. They were built in lieu

of the series of torpedo-boats that were originally planned in the 1887

shipbuilding program.

The vessels of the GENERAL BLANCO class are as follows:

GENERAL BLANCO (1895)

60 tons, 11

knots., Armament: 1 x 42mm/42cal quick-fire gun, 1 machine gun.

The vessel was

named for General Blanco, who served as general-governor of the Philippines at

the time, prior to being sent to Cuba, where he spent the Spanish American War.

Career: She was built

for service on Lanao lake.

Details and fate

are unknown.

LANAO (1895)

60 tons, 11 knots,

Armament: 1 x 42mm/42cal quick-fire gun, 1 machine gun.

The vessel was

named for a lake on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

Career: She was

built for service on Lanao lake.

Details and fate

are unknown.

Specifications: General Blanco, Lanao

General Blanco launched 8/18/1895

Lanao launched 9/22/1895

Displacement 65 tons

Dimensions (length × width × bead height × draft) 25.0 × 4.8

× 2.0 × 1.3 metres

Powerplant 2 propeller shafts, 20 kW

Speed 11 knots

Range 1200 miles (coal 7 tons)

Armament 1 – 42mm, 2 (1 on Lanao) – 25mm, 2 – 11mm mitrailleuse

Crew 29

U.S. Navy (ex-Spanish) gunboat Villalobos

American Gunboat Operations, Philippine Islands

Following the Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, U. S.

Navy ships blockaded Manila until army forces could arrive. In August, army

troops captured the city. Over the next five months, gunboats helped U. S.

troops seize key positions around the islands. When the Philippine-American War

began in February 1899, naval gun- fire helped repulse Filipino attacks on

Manila. In the insurgency that followed, U. S. Navy gunboats provided essential

mobility to American troops and played a vital role in winning the Philippine-

American War. Indeed, gunboats were absolutely essential during an insurgency

that theoretically spanned some 7,000 islands and 500,000 square miles of

terrain.

Rear Admiral George C. Remey, who commanded the Asiatic

Squadron, deployed its gunboats and other small warships to four patrol zones:

one on the island of Luzon; the second on the islands of Panay, Mindoro,

Palawan, and Occidental Negros; the third on the Moro country of the Sulu group

and southern Mindanao; and the last one on the Visayas group composed of Cebu,

Samar, Leyte, Bohol, Oriental Negros, and northern Mindanao from the Straits of

Surigao to the Dapitan Peninsula. Some gunboats patrolled as far away as Borneo

and China to cut off arms shipments to the Filipino guerrillas.

The gunboats patrolled Philippine waters to isolate Filipino

forces on individual islands and interdict the flow of arms and supplies to

them. The gunboats also supported ground operations with fire- power, escorted

troop transports, covered landings, and evacuated endangered garrisons. Ships,

particularly the army’s improvised troop transports, frequently ran aground,

and gunboats then helped pull them free, frequently under hostile fire. At

night, gunboats sailed deep behind insurgent lines, landing and retrieving

scouts who reported on enemy positions and strength. The gunboats maintained

communication with scattered army and marine garrisons and mobile columns and

delivered their supplies, pay, and mail.

To supplement its meager forces, the navy seized 13

former Spanish gunboats and converted yachts and other small civilian craft

to naval service. Most of these gunboats, particularly the converted yachts,

were of small size. They averaged about 90 feet in length and carried a variety

of weapons including 1-, 2-, and 3- pounder guns; 37-millimeter cannon; Colt

and Gatling guns, and various small arms. Among them, however, were a few

heavily armed warships such as the Petrel, an 892-ton, 176-foot gunboat armed

with four 6-inch guns that earned it the nickname “Baby Battleship.”

A landing force from the Petrel seized the important port of Cebu in the first

weeks of the war.

Despite the acquisition of Spanish and converted civilian

ships, the navy could rarely deploy more than two dozen gunboats to patrol the

thousands of islands and numerous navigable rivers of the Philippines.

Dispersed across the islands, gunboats generally operated singly or in pairs.

Fairly typical of gunboat operations were the final

campaigns to secure the island of Samar. Despite earlier campaigns there, including

a celebrated effort by Major Littleton W. T. Waller and 300 marines, Filipino

insurgents continued to operate on Samar, eluding U. S. forces in its dense

jungle and mountainous terrain. In January and February 1902, the gunboats

Frolic and Villalobos carried soldiers on a series of raids on Samar that

yielded valuable intelligence and led to the capture of Filipino commander

Vicente Lukban. Four more gunboats arrived in March, and these allowed their

commander, Lieutenant Commander Washington I. Chambers, to blockade the island,

cutting off vital supplies to the insurgents, particularly food, which Samar

imported from neighboring islands. In April, Chambers’s squadron embarked the

troops of Brigadier General Frederick D. Grant and carried them deep into the

island along its rivers. These forces overran the insurgents’ main camp and harried

them across the island in a three-week campaign that forced their surrender,

ending the war on Samar two months before the official proclamation of peace on

July 4, 1902.

As the war wound down, the navy shifted gunboats to other operations.

Some worked to suppress the slave trade among the Moros in the Sulu

archipelago, southern Mindanao, and southern Palawan. Others hunted pirates in

Philippine and Chinese waters. Gunboats thus played a vital role in the

Philippine-American War. Without them, conquest of the Philippines might well

have been impossible.