The first great strategic debate to face the war cabinet

concerned operations against South Georgia. The island was 800 miles beyond the

primary objective – 800 miles of hostile sea and danger from submarines. It was

largely irrelevant to the recapture of the Falklands, and would probably be

surrendered automatically once the major Argentine positions had been taken. It

seemed a major diversion of effort to dispatch Thompson’s entire brigade to

South Georgia, whatever the attractions for the marines of a rehearsal for

greater things to come. Conversely, the use of only the small force embarked

aboard Antrim and Plymouth seemed too risky. It would be a devastating

beginning to British operations in the South Atlantic to suffer any kind of

failure against such an objective. Virtually the entire navy staff, including

Leach and Fieldhouse, advised against it.

The decision to press ahead against South Georgia, like so

many others of the campaign, was primarily political. The British public was

becoming restless for action, more than two weeks after the task force had

sailed. Buenos Aires remained intransigent. Questions were even being asked in

Washington about Britain’s real will for a showdown. The former head of the

CIA, Admiral Stansfield Turner, suggested on television that Britain could face

a defeat. British diplomacy needed the bite of military action to sharpen its

credibility. To the politicians in the war cabinet, South Georgia seemed to

offer the promise of substantial rewards for modest stakes. The Antrim group

was ordered to proceed to its recapture.

The detached squadron led by Captain Brian Young in Antrim

rendezvoused with Endurance 1,000 miles north of South Georgia on 14 April. The

British believed that the Argentinians had placed only a small garrison on the

bleak, glacier-encrusted island. The submarine Conqueror, which left Faslane on

4 April, had sailed direct to the island to carry out reconnaissance for the

Antrim group. She slipped cautiously inshore, conscious that an iceberg 35 by

15 miles wide and 500 feet high had been reported in the area. Her captain

reported no evidence of an Argentine naval presence. The submarine then moved

away north-westwards to patrol in a position from which she could intervene

either in the maritime exclusion zone, or in support of the South Georgia

operation, or against the Argentine carrier, if she emerged. A fifteen-hour

sortie by an RAF Victor aircraft confirmed Conqueror’s report that the approach

to South Georgia was clear.

On 21 April, Young’s ships saw their first icebergs, and

reduced speed for their approach to the island, in very bad weather. The

captain summoned the marine and SAS officers to his bridge to see for

themselves the ghastly sea conditions. The ship’s Wessex helicopters

nonetheless took off into a snowstorm carrying the Mountain Troop of D

Squadron, SAS, under the command of twenty-nine-year-old Captain John Hamilton.

Antrim had already flown aboard a scientist from the British Antarctic Survey

team which successfully remained out of reach of the Argentinians through the

three weeks of their occupation of South Georgia. This man strongly urged

against the proposed SAS landing site, high on the Fortuna Glacier, where the

weather defied human reason. Lieutenant Bob Veal, a naval officer with great

experience of the terrain, took the same view. But another expert in England

very familiar with South Georgia, Colonel John Peacock, believed that the

Fortuna was passable, and his advice was transmitted to Antrim. The SAS admits

no limits to what determined men can achieve. After one failed attempt in which

the snow forced the helicopters back to the ships, Hamilton and his men were

set down with their huge loads of equipment to reconnoitre the island for the

main assault landing by the Royal Marines. One SAS patrol was to operate around

Stromness and Husvik; one was to proceed overland towards Leith; the third was

to examine a possible beach-landing site in Fortuna Bay.

From the moment that they descended into the howling gale

and snowclad misery of the glacier, the SAS found themselves confounded by the

elements. ‘Spindrift blocked the feed trays of the machine guns,’ wrote an NCO

in his report. ‘On the first afternoon, three corporals probing crevasses

advanced 500 metres in four to five hours . . .’ Their efforts to drag their

sledges laden with 200 pounds of equipment apiece were frustrated by whiteouts

that made all movement impossible. ‘Luckily we were now close to an outcrop in

the glacier, and were able to get into a crevasse out of the main blast of the

wind . . .’ They began to erect their tents. One was instantly torn from their

hands by the wind, and swept away into the snow. The poles of the others

snapped within seconds, but the men struggled beneath the fabric and kept it

upright by flattening themselves against the walls. Every forty-five minutes,

they took turns to crawl out and dig the snow away from the entrance, to avoid

becoming totally buried. They were now facing katabatic winds of more than 100

m.p.h. By 11 a.m. the next morning, the 22nd, their physical condition was

deteriorating rapidly. The SAS were obliged to report that their position was

untenable, and ask to be withdrawn.

The first Wessex V to make an approach was suddenly hit by a

whiteout. Its pilot lost all his horizons, fell out of the sky, attempted to

pull up just short of the ground and smashed his tail rotor in the snow. The

helicopter rolled over and lay wrecked. A second Wessex V came in. With great

difficulty, the crew of the crashed aircraft and all the SAS were embarked, at

the cost of abandoning their equipment. Within seconds of takeoff, another

whiteout struck the Wessex. This too crashed on to the glacier.

It was now about 3 p.m. in London. Francis Pym was boarding

Concorde to fly to Washington with a new British response to Haig’s peace

proposals. Lewin, anxiously awaiting news of the services’ first major

operation of the Falklands campaign, received a signal from Antrim. The

reconnaissance party ashore was in serious difficulty. Two helicopters sent to

rescue them had crashed, with unknown casualties. For the Chief of Defence

Staff, it was one of the bleakest moments of the war. After all his efforts to imbue

the war cabinet with full confidence in the judgement of the service chiefs, he

was now compelled to cross Whitehall and report on the situation to the Prime

Minister. It was an unhappy afternoon in Downing Street.

But an hour later, Lewin received news of a miracle. In a

brilliant feat of flying for which he later received a DSO, Lieutenant

Commander Ian Stanley had brought another helicopter, a Wessex III, down on the

Fortuna Glacier. He found that every man from the crashed helicopters had

survived. Grossly overloaded with seventeen bodies, he piloted the Wessex back

to Antrim and threw it on to the pitching deck. His exhausted and desperately

cold passengers were taken below to the wardroom and the emergency medical

room.

A disaster had been averted by the narrowest of margins. Yet

the reconnaissance mission was no further forward. Soon after midnight the

following night, 23 April, they started again. 2 Section SBS landed

successfully by helicopter at the north end of Sorling Valley. Meanwhile, fifteen

men of D Squadron’s Boat Troop set out in five Gemini inflatable craft for

Grass Island, within sight of the Argentine bases. For years, the SAS had been

vainly demanding more reliable replacements for the 40 h.p. outboards with

which the Geminis were powered. Now, one craft suffered almost immediate engine

failure and whirled away with the gale into the night, with three men helpless

aboard. A second suffered the same fate. Its crew drifted in the South Atlantic

throughout the hours of darkness before its beacon signal was picked up the

next morning by a Wessex. The crew was recovered. The remaining three boats,

roped together, reached their landfall on Grass Island but, by early afternoon,

they were compelled to report that ice splinters dashed into their craft by the

tearing gale were puncturing the inflation cells. The SBS party in Sorling

Valley was unable to move across the terrain, and had to be recovered by

helicopter and reinserted in Moraine Fjord the following day. All these

operations provided circumstantial evidence that the Argentine garrison ashore

was small. But they were an inauspicious beginning to a war, redeemed only by

the incredible good fortune that the British had survived a chapter of

accidents with what at this stage seemed the loss of only one Gemini.

On 24 April, the squadron received more bad news: an enemy

submarine was believed to be in the area. The British already knew that

Argentine C-130 transport aircraft had been overflying the island, and had to

assume that the British presence was now revealed. Captain Young dispersed his

ships, withdrawing the RFA tanker Tidespring carrying M Company of 42 Commando

some 200 miles northwards. It seemed likely to be some days before proper

reconnaissance could be completed, and any sort of major assault mounted. Above

all, nothing significant could be done until more helicopters arrived. That

night, the Type 22 frigate Brilliant joined up with Antrim after steaming all

out through mountainous seas from her holding position with the Type 42s. She

brought with her two Lynx helicopters. Captain Young and his force once again

moved inshore, to land further SAS and SBS parties. British luck now took a

dramatic turn for the better.

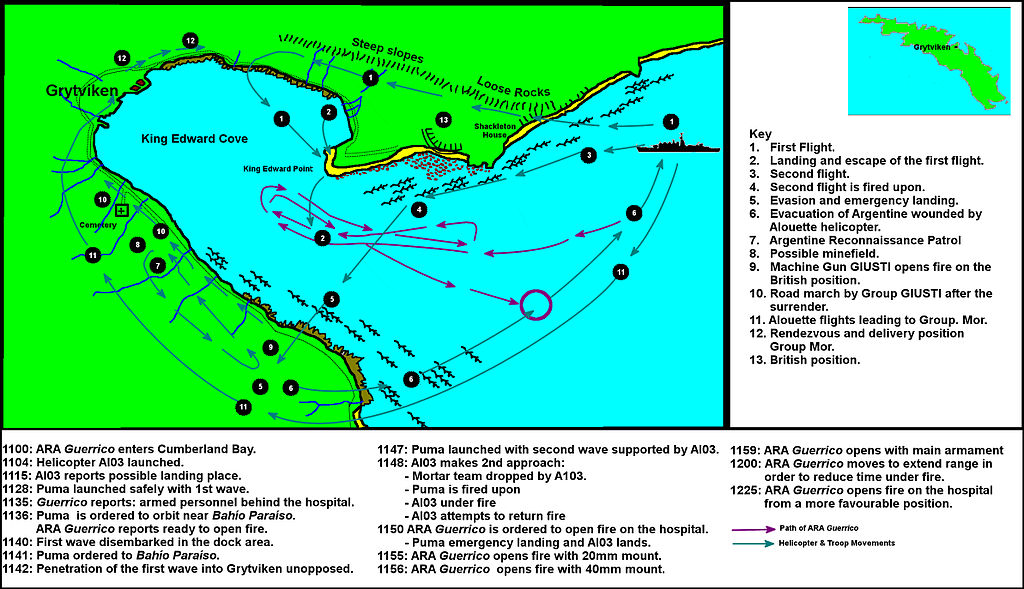

Early on the morning of 25 April, Antrim’s Wessex III picked

up an unidentified radar contact close to the main Argentine base at Grytviken.

Endurance and Plymouth at once launched their Wasps. The three helicopters

sighted the Argentine Guppy class submarine Santa Fe heading out of Cumberland

Bay, and attacked with depth charges and torpedoes. Plymouth’s Wasp fired an AS

12 missile, which passed through the submarine’s conning tower, while

Brilliant’s Lynx closed in firing GP machine-guns. It may seem astonishing

that, after so much expensive British hardware had been unleashed, the Santa Fe

remained afloat at all. It was severely damaged, and turned back at once

towards Grytviken, where it had been landing reinforcements for the garrison,

now totalling 140 men. There, the submarine beached herself alongside the British

Antarctic Survey base. Her crew scuttled hastily ashore in search of safety.

There was now a rapid conference aboard Antrim, and urgent

consultation with London. The main body of Royal Marines was still 200 miles

away. But it was obvious that the enemy ashore had been thrown into disarray.

Captain Young, Major Sheridan of the marines and Major Cedric Delves,

commanding D Squadron, determined to press home their advantage. A composite

company was formed from every available man aboard Antrim – marines, SAS, SBS –

seventy-five in all. In the cramped mess-decks of the destroyer, they hastily

armed and equipped themselves. Early in the afternoon, directed by a naval

gunfire support officer in a Wasp, the ships laid down a devastating

bombardment around the reported Argentine positions. At 2.45, under Major

Sheridan’s overall command, the first British elements landed by helicopter and

began closing in on Grytviken. There was a moment of farce when they saw in

their path a group of balaclava-clad heads on the skyline, engaged them with

machine-gun fire and Milan missiles, and found themselves overrunning a group

of elephant seals. Then they were above the settlement, where white sheets were

already fluttering from several windows.

As the SAS led the way towards the buildings, a bewildered

Argentine officer complained, ‘You have just walked through my minefield!’ SAS

Sergeant Major Lofty Gallagher ran up the Union Jack that he had brought with

him. At 5.15 local time, the Argentine garrison commander, Captain Alfredo

Astiz, formally surrendered. He was an embarrassing prisoner of war, as he was

wanted for questioning by several nations in connection with the disappearance

of their citizens while in government custody on the Argentine mainland some

years earlier. Britain was eventually to return him to Buenos Aires,

uninterrogated. Somewhat reluctantly, the fastidious Royal Navy began to embark

a long column of filthy, malodorous and dejected prisoners aboard the ships.

The following morning, after threatening defiance by radio overnight, the small

enemy garrison at Leith, along the coast, surrendered without resistance. The

scrap merchants whose activities had precipitated the entire drama were also

taken into custody, for repatriation to the mainland.

The British triumph became complete when a helicopter picked

up a weak emergency-beacon signal from the extremity of Stromness Bay. A

helicopter was sent, managed to home on it, and recovered the lost three-man

SAS patrol whose Gemini had been swept away in the early hours of 23 April.

They had paddled ashore with only a few hundred yards of land left between them

and the Atlantic. Thus, with a last small miracle, the British completed the

recapture of South Georgia, the first operation of the Falklands campaign, without

a single man lost. One Argentine sailor had been badly wounded and one was

killed the following day in an accident.

The news of the operation was immediately relayed back to

London. A sense of relief turned to euphoria. Two days earlier, Mrs Thatcher had

personally visited Northwood to be briefed by Field-house and his staff and to

endure with them the agonised suspense of the SAS and SBS debacles. Her

constant supportive remarks to the fleet staff made a deep impression. The

simplicity of her objectives and her total determination to see them achieved

came as a welcome change to men used to regarding politicians as hedgers and

doubters.

Sunday’s news was greeted by the public as a triumph long

expected and not a little overdue. The British people had, after all, been led

to believe that the task force was irresistible. As a result, when Mrs Thatcher

joined John Nott on the steps of Downing Street and called to waiting pressmen,

‘Rejoice, just rejoice!’ it seemed a curiously hard and inappropriate heralding

of the onset of war. Yet it was the reaction of a woman overwhelmed with

relief. The first stage of her gamble had only narrowly been rescued from

catastrophe.

The euphoria was not confined to London. On 26 April, aboard

his flagship Hermes, Admiral Woodward gave a rare interview to a task-force

correspondent, in which he declared robustly, ‘South Georgia was the appetiser.

Now this is the heavy punch coming up behind. My battle group is properly

formed and ready to strike. This is the run-up to the big match which, in my

view, should be a walkover.’ The British were told, he said, that the

Argentinians in South Georgia were ‘a tough lot. But they were quick to throw

in the towel. We will isolate the troops on the Falklands as those on South

Georgia were isolated.’ Woodward subsequently denied much of the substance of

that interview as reported in the British press. But, to many of his officers,

it had the authentic flavour of the admiral, anxious to inspire the greatest

possible confidence in what his task force could do.