William B. Fawcett

Only in the loosest sense, was the

pre-conquest Aztec nation a nation in the European meaning of the word. The

very concept of nation would have been virtually inconceivable to the average

Aztec. He was a Texcocan or a Tlaxcalan. The Aztec nation was, in fact, a

patchwork of city states with varying degrees of independence and mutual

animosity. An individual’s allegiance was to his clan and tribe. (Most cities

were inhabited by one tribe which was determined by customs and deities

worshipped more often than common ancestry.)

The Aztec “empire” was in fact a

conglomeration of city states that formed rather fluid coalitions which were

normally centered on the most powerful cities found in the area of present day

Mexico City. In these coalitions there were normally one or two major powers

who, by their size and military strength, were able to compel the lesser cities

to join in their efforts. When a city was ‘conquered’ the result was the

imposition of tribute and economic sanctions rather than social or political

absorption, as occurred in Europe or China. This tribute was reluctantly paid

to the victorious city only until some way to avoid it was found (such as an

alliance to an even more powerful city). Any political or military alliance was

then ruled entirely by expedience, and quickly and easily dissolved.

This constant shifting was demonstrated by

the actions of Texcoco when Tenochtitlan, then the chief power, was attacked by

Cortes. Texcoca joined with several other cities in aiding the Spanish. Just a

few years earlier Texcoco had been the reluctant ally of Tenochtitlan in her

unsuccessful war with Tlaxcalans. (During which the Tenochtitlans arranged to

have the Tlaccalans ambush a part of the Texcocans involved. Such treacheries

were not uncommon.) Later the Spanish were able to play these former allies

against each other.

The citizen of an Aztec city was imbued

from birth with the concept that the city and tribe were important and the

individual should act only in ways that benefited the whole. The concept of

individualism we value would have been considered anti-social and obscene to

the Aztecs. Though they amassed individual wealth and possessions most of the

land was considered to either belong to the tribe outright or to be held in

trust for the city by the individual. Anyone dying without an heir (male, son)

automatically left his land and possessions to the city or clan for

redistribution. Material wealth was considered less important than value to the

tribe, as reflected by the positions held and honors received. If you do not

realize how deeply this selfless spirit was ingrained in every citizen, it will

be difficult to accept the attitudes demonstrated by captured warriors.

War itself was viewed by the Aztecs as a

part of the natural rhythms. These rhythms were felt to permeate every level of

existence and only by keeping in step to them could an individual and (more

importantly) a tribe or city survive and prosper. Each day was seen as a battle

between the sun and the earth. The sun losing every sunset and gladly sacrificing

himself to the earth, so that men could prosper. Many of the workings of nature

were viewed as being reflections of the rhythm of the war between the opposing

natural and spiritual forces. War then took on a religious and ritual nature

that both limited it in extent and made it part of the spiritual life of the

community with strong metaphysical overtones. Rituals arose around the

conducting of wars and to vary from them would have caused the war to lose its

very reason for existing. On the more mundane level wars were fought for

Revenge, Defense, or Economic reasons. A common cause for the formal

declaration of war was that a city’s merchants were being discriminated against

or attacked. (These merchants normally doubled as each city’s intelligence

force and so were often harassed in times of high tensions.) Behind all

political and economic justifications was always the strong force of the

religious nature of war, and a never ending need for captives to sacrifice.

A common proximate cause for war was the

failure of a vassal state to pay the tribute demanded. It is surprising to

discover, but true, that in a system where tribute was one of the key

ingredients, no system (such as hostages) was ever devised to guarantee the

payment of tribute from a previously conquered area. If tribute was refused the

only alternative was to go to war again.

The process of declaring war was long and

elaborate. Followed in most cases, it left no room for the deviousness common

in Aztec wars. The procedure to be followed was set in a series of real, but

ritually required, actions. The actual declaration of war involved three State

visits, often by three allied cities planning to attack. The first delegation

called on the chief and nobles of the city. They boasted of their strength and

warned that they would demand some of the nobles as sacrifices if the war

ensued. The group would then retire outside the city gate and camp for one

Aztec month (20 days) awaiting a reply. This was normally given on the last day

and if the city or coalition did not accept their terms, token weapons were

distributed to the nobles. (This was so that no one could say they defeated an

unarmed foe.)

The second delegation would then approach

the city’s leading merchants. This second delegation would describe the

economic “horrors” of a defeat, comparing them badly to the terms

offered, and generally trying to persuade the merchants to get the chiefs to

surrender. This delegation then also retired for a month to await a reply.

Should this also be negative a third and final delegation would arrive. This

group was to talk to the warriors themselves. They would harangue a mass

meeting with reasons why they should not fight and tales of the horrors of

battle. Once more they would ask for the city to meet their terms (normally a

virtual surrender or the loss of some territory) and then retire to a camp for

the ritual one month wait. Finally, after all of this, the armies (having had

plenty of time to assemble) would meet in a battle. Here any deception was

acceptable and a cunning general as valuable as a courageous one.

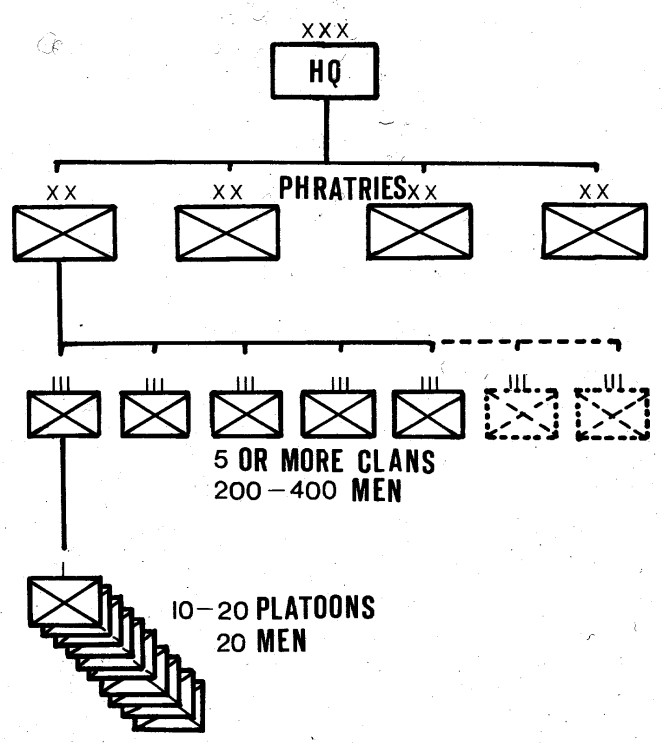

The leadership of the Aztecs was the same

in times of peace and war. Between wars the officers served as the

administration, judiciary, and civil service of the city. Heading this organization

was the Supreme War chief or Tlacatecuhtli. This was the position held by the

unfortunate Montezuma in Tenochtitlan when Cortes arrived. Each clan was

assigned to one of four phratries each having its own leader called a Tlaxcola

who served as their divisional commander in wartime, and on a council with the

other three that ran the actual administration of the city in times of peace.

The head of each clan served as a regimental commander and was known as a

Tlochcautin. In peace he would serve in a role similar to the English Sheriff.

Below the clan level was a unit of approximately 200 to 400 men. This was the

equivalent of our company and was really the largest unit over which any

tactical control could be held once a battle began. The smallest regular unit

was the platoon of 20 men. This organization was rigidly observed by the major

cities and was such an integral part of Aztec culture that the symbol for ’20’

was a flag such as each platoon had.

The military techniques of the Aztecs were

inferior to those of Europe or China at that time. This is probably due

primarily to the fact that while ritually involved and religiously important,

war was less developed as a social solution in pre-conquest Mexico. This was

caused by several factors, the major one being that the population density of

the area was much less than in other parts of the world. In the period

immediately preceding the Spanish only one area had really felt the pinch of

overpopulation. This was the area around Lake Titicocca occupied today by

Mexico city. Here is where the powerful and most warlike cities developed. Even

then their tradition of war (as opposed to individual combat) was only a few

hundred years old as opposed to thousands in other lands. The result was that

while having a warrior attitude and with war deeply ritually ingrained in their

culture, the techniques of battle were still quite unsophisticated and basic.

One reflection, of the undeveloped nature

of Aztec wars was the absence of any sort of drills. Units acted as a group

only during civil duties, or during the several religious ceremonies that they

assembled for each year. The tactics of a battle then most often resembled the

mass or swarm tactics of biblical times.

Another factor mitigated in favor of only

limited military activities. This was the fact that it was extremely difficult

for an army to engage in an extended campaign. Since the army was also the work

force, a campaign during the planting and harvest seasons was prohibited. This

is especially true since the agriculture was not so efficient as to be able to

support the massive priests hierarchy and a standing army of any size. Nor

could an army live off of the country, since it was likely that the area they

would travel through would be inhabited by several city states that were not

involved in the war and were independent of those involved. This meant that it

was necessary not only to set up supply depots along any proposed route, but

also to negotiate permission to trespass on other cities’ lands.

The marginal nature of the agriculture was

also such, that sieges that lasted any length of time were virtually

impossible. The besieging army would as likely starve as the besiegers. The

result of this was that formal walls and other fortifications were rare. In

their place canals (useful in trade also) were often used with portable

bridges. Many cities were also located in easily defensible terrain such as on

a mountainside or on the end of a narrow isthmus. There has also been no

evidence that siege weapons of any sort were developed or used to any extent.

Despite all of the problems listed the Aztecs were able to wage campaigns over

a wide area of Mexico. Most often these were fought with armies made up chiefly

of local allies with a contingent of Aztecs to stiffen them. In some cases it

is recorded that the Aztecs were forced to engage in the laborious technique of

having to subdue each of the towns and cities on their route.

The weapons and tools of the Aztecs were

basic and simple in nature. Rather than developing new variations of weapons

the efforts of the Aztecs went into elaborate decorations on them. There were

four main weapons used by the Aztec warrior. A wooden club with sharp obsidian

blades was used. Javelins were common and often used with a throwing stick

called an atl-atl. The bow and arrow was also found in most armies as was a

heavy javelin or lance for in-fighting. Occasionally a clan would have a

tradition that caused some of them to employ the sling or spears. Axes were

used as tools, but do not seem to have been a regularly used weapon.

The bulk of the weapons in a city was kept

in an arsenal called the Tlacochcalco or roughly the “house of

darts.” One of these was found in each quarter of a city and held the

weapons for five clans (one phratrie). These arsenals were always located near

the chief temples and were designed with sloping walls that enabled them to

serve as a fort. The Tlacochcalcos served as the headquarters, assembly points

and rallying points for the defenders of a city. Religious ceremonies were also

held there by the military leaders and “Knights.”

The shields of the Aztecs were wickerwork

covered with hide. Most were circular and elaborately painted and decorated.

Skins and feathers were also often attached to augment their beauty. The

warriors who used the clubs carried shields, but those using the large javelin

or lance were unable to as they needed both hands to employ their weapon. Body

armor was made of quilted cotton hardened in brine. This was quite successful

against the weapons used by other Aztecs, (and useless against crossbows and

steel swords). This cotton armor was in fact quickly adopted by the

conquistedores as being effective enough and much cooler than their own metal

armor. The quilted armor was often dyed bright colors, brocaded and embroidered

with intricate designs and symbols.

Wooden helmets were worn by some warriors

and the chiefs, (who rose to chief by being outstanding warriors). These

quickly became elaborate and bulky. It was often necessary for them to be

supported by shoulder harnesses. Most headdresses or helmets were stylized

animals or protecting deities. The more elaborate the helmet the more renown

the warrior in battle. There is mention of copper helmets in a few codexs, but

none have been found and in any case would have been extremely rare. Metal

working for tools and weapons was not advanced and obsidian was the basic (and

effective) material.

As during comparable periods on other

continents the Aztecs wore no uniforms. Each side would identify itself with a

prominently worn badge or insignia. This often would be elaborated to show also

the rank of the wearer. With the myriad of colors in the cotton armor and the

elaborate helmets an Aztec battle was a kaleidoscope of swirling colors. A

young warrior was taught the use of weapons as part of his schooling. (All males

were soldiers.) All boys were required to either be tutored or to attend the

Telpuchcalli or public school. Later, in lieu of unit training and drills, a

new warrior was attached to veteran for his first battles. This program was

actually quite similar to the apprenticeship or squire systems developed for

the same purpose in medieval Europe.

The tactics and weapons of the Aztecs were

greatly influenced by the goal of their wars, captives and whatever tribute or

land demanded. It was the ultimate sign of ability in a warrior to bring back

from a battle a live enemy suitable for sacrifice. Warriors then often strived

not to kill their enemy, but to knock him out or deliver a non-fatal, but

disabling wound. A victory was valued then by the number of enemies captured,

not killed. To this end warriors were trained rigorously in individual combat,

with little emphasis on formations or teamwork. The best warriors were admitted

to select societies of “knights.” Only the most skillful

(as judged purely by the number of captives

taken) were allowed to enter. These were known as the Knights of the Eagle, the

Knights of the Ocelot (Tiger), and a less common group the Knights of the

Arrow. Helmets depicting their namesakes were often worn and ceremonial

costumes that copied their coloration were worn in ceremonies and into battle.

These orders performed dances and participated in rituals at the Tlacochcalco.

They also participated in the mock battles of sacrifice. These Knights received

large shares of land when conquered territories were divided between the

warriors. (This practice gave an occupation force a way to support itself.)

A warrior who was slain in battle or

sacrificed after a defeat was guaranteed entry into a special warriors heaven.

This was to be found in the East and a special heaven for women who died in

childbirth was in the West (they were felt to have sacrificed themselves for a

potential new warrior). To die in these ways was the greatest honor a defeated

warrior could receive. (Non-warriors and cowards were sold into slavery.) To

some it was the culmination rather than the ruin of the lives. There is

recorded the story of Tlahuicol who was a Tlaxclan chief. Having been captured

in battle he was given the honor of the mockgladitorial sacrificial combat.

This meant that he was chained to a large round stone representing the sun and

given wooden weapons, (no obsidian points or edges), and attacked one at a time

by members of the Knights of the Eagle. In single combat he managed to kill a

few and wound several more. The combat was stopped and Tlahuicol was offered

the choice of the generalship of the Tlaxclan army or to be the sacrifice in

their highest ritual. He choose to be the sacrifice, viewing it probably as the

greater honor.

These sacrifices were viewed then not as a

punishment (criminals were killed or enslaved, but never sacrificed), but as an

opportunity to give their final great contribution to their communities. It was

believed that the sacrifices were needed to prevent the wrath of the gods and

bring anything needed such as the rain or spring. Perhaps the only close honor

was to obtain a prisoner in battle.

A typical Aztec battle consisted of both

sides coming upon each other, quickly forming up to charge and then rushing at

each other amid fierce cries. Quickly this would break down into many combats

between individuals and small groups. Both sides would contend, until one

seemed to be gaining an advantage. The other would then break and run, avoiding

capture to minimize their enemy’s victory. Often the defeat and capture of a

major chief was enough to cause the morale of one side to break.

Many stratagems were used. Feints and

deception were common, especially in the battles between the major cities. It

was a common maneuver for one side to fake a route and then lead their pursuers

past a second force in hiding. This force would then fall on the rear of their

pursuers while the routing force rallied. A cunning war chief was considered as

valuable as a courageous one. Whoever won, sacrifices were assured and the gods

appeased.

If there was no war occurring, then an

artificial war was instituted to assure sacrifices and give the warriors an

opportunity to prove their skills. This was incongruously named the “War

of Flowers.” Though it was an artificial war those participating in it

fought a very real battle. Many died and many more were captured for sacrifice

before one group would concede defeat.

Invited to participate were the best

Knights and warriors of two or more rival states. The best warriors contended

to be able to participate. If he won, a warrior would gain in renown throughout

the cities. If he was killed, the warrior was given the honor of cremation.

Reserved only for warriors, cremation guaranteed entrance to the special

warriors’ heaven. Finally, if defeated and captured a warrior was given the

supreme honor of being sacrificed. So popular were these Wars of Flowers that

some were repeated annually for years.

The institution of war among the Aztecs

evolved into something quite different from that which we perceive. It was

foremost a means by which an individual could serve the all important tribe or

city. It was an inherently ritualized and mystic event of deep-meaning and

necessity. It was the only means by which captives needed to appease their

bloodthirsty gods (actually it was the hearts they tore out and offered still

throbbing). In a truly collective, military society it was the one area where

an individual could gain renown and prestige.

Aztec Command Structure

Tlacatecuhtli -War chief, C in C

Tlaxcola – Phratry Commander (4)

Tlochcautin – Clan Commander