Late 1941 and early 1942 saw Britain’s darkest hours, pushed

back in the Western Desert and with its eastern empire crumbling to Japanese

aggression, the country stood alone with only the Atlantic convoys keeping the

country afloat. These convoys were threatened by one of Germany’s greatest

weapons, the Tirpitz, a battleship that far outclassed anything in the British

armoury. The sheer size of the ship limited it to only a few ports where it

could be repaired if it were to be damaged, a dry dock of immense proportions

would be required, the only one that could be accessed from its main hunting

ground, the Atlantic Ocean, was at Saint Nazaire, in western France. Originally

constructed for the ocean liner ‘Normandie’, the dry dock was itself an

impressive structure and an impossible target to destroy from the air. A force

would have to be landed and destroy it with explosives, this was the task

handed to the chief of Combined Operations, Lord Louis Mountbatten.

A force of Commandos was to be taken six miles up the Loire

estuary to Saint Nazaire aboard an antiquated destroyer packed with explosives

and modified to resemble a German destroyer. The vessel would ‘bluff’ its way

past the many German defensive positions using captured recognition codes, the

destroyer would then ram the dry dock gates, set a fuse and disembark the

Commandos who would set about various sabotage tasks. This force was to be

escorted by eighteen small motor launches, who would then embark the Commandos

and withdraw. It was an impossible task, perhaps the only chance of success was

the Germans would never imagine the British to carry out such an audacious

raid.

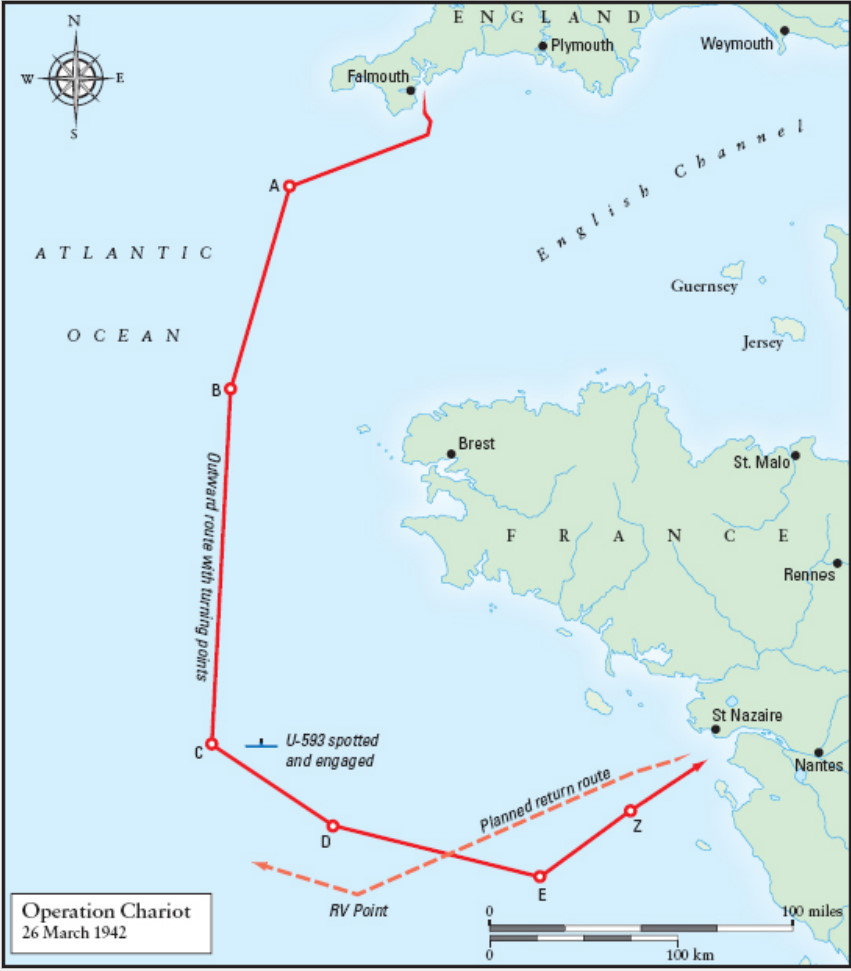

The Plan

As they sailed steadily towards the open sea the force

changed formation into Cruising Order No. 1, which was their simulation of an

anti-submarine sweep. On Atherstone’s signal, the longitudinal columns to port

and starboard of the destroyers opened out from the rear until they were

disposed in the form of a broad, open arrowhead, four cables behind the tip of

which steamed Atherstone. In the open spaces to the rear of each ‘wing’ steamed

Campbeltown, still with the MTB in tow, and Tynedale.

Remembering that fine first day, Newman, who with his staff

was being made very comfortable on board the Atherstone, writes that ‘the

thrill of the voyage was upon me – the study of the navigational course with

the Navy – the continuous lookout for enemy aircraft – the preparation of one’s

own personal kit to land in – and the deciphering and reading of W/T messages

from the Commander-in-Chief made night fall on us in no time.’

Across in Campbeltown, Copland and the eighty-odd men of his

Group Three parties were being made just as welcome by the truncated crew of

the old destroyer. ‘There was little to do’ he remembers; ‘all our preparations

had been made on PJC and it only remained to arrange our tours of duty for AA

Defence, rehearse “Action Stations” and wait. Troops and sailors were very

quickly “buddies”, and as no khaki was allowed to be seen on deck the limited

number who were allowed up . . . appeared in motley naval garb, anything from

oilskins to duffle coats, not forgetting Lieutenant Burtinshaw who discovered

one of Beattie’s old naval caps and wore it during the whole voyage. During

this first day too, we allocated all our landing ladders and ropes in places on

deck where we thought they would be most wanted. Gough [Lieutenant Gough, RN,

Beattie’s No. 1] was to be in charge of all tying-up and ladder control and his

help in the allocation was invaluable.’

In the MLs also the pattern of ready camaraderie between

‘pongos’ and ‘matelots’ was quickly established, the representatives of the two

services managing to live cheek-by-jowl in the crowded living spaces without

dispute. Feeding more than twice the normal complement of men from the limited

resources of the tiny midships galley was something of a problem for the

designated cook, although in the early stages of the voyage seasickness, or the

fear of it, robbed more than a few Commandos of their appetites. Tough as they

might have been on dry land, some Commandos had nonetheless blanched at the

mere thought of doing battle with the fearsome Bay of Biscay; typical of these

was Bombardier ‘Jumbo’ Reeves, of Brett’s demolition party for the inner

dry-dock caisson. A member of 12 Commando who had volunteered from the Royal

Artillery, Jumbo was a qualified pilot whose aerial ambitions had been dashed

as the result of an extreme susceptibility to airsickness. As one of those

unfortunates whose stomach tended to come up with the anchor cable, he had had

pronounced misgivings about setting off from Falmouth. For Jumbo, as for many

others, the unexpected quiescence of the sea came, therefore, as a gift from

God.

In the crowded messdecks as the sailors came and went with

the changing of the watches, the Commandos talked and smoked, dozed on the

matelots’ bunks, played cards and checked and re-checked their equipment. Proud

of their hard-won skills, they were happy to demonstrate their prowess to their

hosts, such as the nineteen-year-old Ordinary Seaman Sam Hinks, the forward

Oerlikon gunner on ML 443, who had gone so far as to change his name so that

his parents couldn’t stop him from joining up. As with so many of the other

young sailors, who, unlike their thoroughly briefed Commando brothers, were

only now being made aware of their target’s identity, Sam was still coming to

terms with the fact that they were really on their way to attack a distant

foreign port. In keeping with the times when foreign travel was still the

exclusive preserve of the monied classes, Sam knew little of France and nothing

at all of this place called St Nazaire: in fact, when first hearing the name

during a conversation with a Commando by the forward gun, he recalls that, ‘St

Nazaire meant as much to me as if you were going to Timbuktu!’

Having opened their sealed orders once clear of land, the

reaction of the officers to the revelation of their target’s identity had

generally been that this was a port into which no one with any common sense

would wish to sail without benefit of armour plate and heavy guns.

Across on the starboard wing of the formation, ‘Temporary

Acting’ Sub-Lieutenant Frank Arkle, the twenty-year-old First Officer of ML

177, who before the war had been a clerk in the offices of W.D. and H.O. Wills,

greeted the news with ‘some uncertainty and a sort of cold resignation’. Behind

him in England were his family, his friends, and his childhood sweetheart, Meg;

ahead lay a task of prodigious difficulty from which none could confidently

expect to return. It was a prospect about which he and many others found it was

best not to think too deeply. Better by far to focus on not letting the side

down and leave all the rest to fate.

On board the gunboat, which was swinging like a pendulum at

the end of Atherstone’s tow, Curtis had briefed his crew shortly after the

force adopted its cruising formation, prompting Chris Worsley to conclude that

they were all embarked upon a very ambitious and dangerous enterprise.

Strangely, though, considering all the circumstances, he neither thought of,

nor worried about, survival, as it simply never struck him that he might be

killed.

Closer to the centre point of the formation, Lieutenant Tom

Boyd, RNVR, the skipper of the torpedo-armed ML 160, was concerned about how

well the force would perform in action, bearing in mind its poor overall

standard of training. There simply hadn’t been time to school the crews

properly in working as a cohesive unit; as evidence of their lack of

preparedness he could cite the same poor standards of station-keeping that were

worring Ryder himself. Indeed, during the course of this first day Ryder would

make no less than fifty signals to boats, instructing them to close up.

Standing on the bridge of Billie Stephens’ ML 192 Leading

Telegraphist Jim Laurie, from Coldstream in Scotland, learned of his fate from

the skipper himself. A regular, who had joined the Navy in 1936 at the age of

only sixteen, Jim had led something of a charmed life, having survived the

sinking of the destroyer Delight, as well as the loss to a mine of ML 144,

while he was fortunate enough to be on leave. Looking back at the

fast-disappearing coastline, Stephens said to him, ‘Do you think if you jumped

overboard you could swim back to Falmouth?’ Replying in the negative, Jim was

then told, ‘Right. You can go in the wheelhouse and study the maps and you’ll

see just where we’re going.’ For Jim, as for all the sailors, there was never a

question of choice. The highly trained Commandos had been offered a get out,

while the much less experienced sailors had not; yet, once they were under the

German guns, the risk for all would be the same.

Standing as an example of so many of the sailors, who, on

hearing for the first time what was expected of them, rapidly concluded that

someone, somewhere must have a screw loose, was Stoker Len Ball of Ted Burt’s

ML 262. A twenty-five-year-old process chemical worker from Barking in Essex,

Len could not believe that they really intended to sail right through the front

door of such a heavily defended base in boats that were little better than

tinder boxes. After the briefing he returned to the engine room and thought

about it all; the more he thought about it, the more impossible it seemed. He

was no more privy than were his pals to all the details of the German guns that

lay in wait to greet them, but he knew that, provided the Jerry gunners did

their jobs right, there were more than enough of them to cause very substantial

damage indeed.

Waiting for Len and the other ‘Charioteers’, along either

bank of the estuary as well as in and around the port itself, were some seventy

pieces of ordnance, varying in calibre from 20mm quick-firing cannon all the

way up to the huge 240mm railway guns of Battery Batz, a little way west of La

Baule.

Under the overall command of the See Kommandant Loire,

Kapitän zur See Zuckschwerdt, who was headquartered in La Baule itself, these

consisted of two main classes of weapon, each designed to fulfil a specific

purpose. Emplaced so as to defend the approaches to the estuary were the heavy

batteries of Korvettenkapitän Edo Dieckmann’s 280th Naval Artillery Battalion,

with Dieckmann himself headquartered close by the gun battery and Naval Radar

Station on Chémoulin Point. While for the dual-purpose defence of the port

itself there were waiting the three battalions of the 22nd Naval Flak Brigade,

commanded by Kapitän zur See Mecke, whose own headquarters were situated close to

Dieckmann’s at St Marc.

Ranging in calibre through 75, 150, 170 and 240mm,

Dieckmann’s coastal guns were arranged in battery positions, primarily along

the northern shore of the estuary, close to which lay the deep-water channel

which any ship of substance must use in order to reach the port. These fixed

emplacements began at the estuary mouth, and ran eastwards as far as the

Villès-Martin – Le Pointeau narrows, at which point the sea-space was reduced

to a mere 2.25 sea miles, and beyond which lay the province of Mecke’s Flak

Brigade.

Approaching the estuary mouth in their attack formation of

two long parallel columns extending over almost 2, 000 metres of sea, with the

gunboat in the van, and Campbeltown steaming between the leading troop-carrying

MLs, the ‘Chariot’ force would find itself entering into a perfect trap from

which it would be the very devil to escape. On their starboard beam and

guarding the southern extremity of the estuary shore would be the 75mm guns of

Battery St Gildas; while to port, and guarding the north, there would be

railway guns just inland from the Pointe de Penchâteau. Fine on their starboard

bow, as they approached across the shallows, would be the guns of Battery le

Pointeau, backed by the 150cm searchlight ‘Yellow 3’; fine to port would be the

cluster of batteries comprising the 150mm guns of Battery Chémoulin and the

75mm and 170mm cannon of the cliff-top position close by the Pointe de l’Eve.

Backing the cliff-top emplacements was the 150cm searchlight ‘Blue 2’.

It was to divert the attention of these defences that the

diversionary air raid had been proposed, for without it the ‘Charioteers’ would

be forced to rely on luck, their low silhouettes, their unexpected line of

approach and such devices as Ryder believed might confuse the enemy into

mistaking them for a friendly force. Either way, with or without the bombers,

this passage of the outer portion of the estuary would be fraught with danger,

including that from mines, patrol vessels and possibly even Schmidt’s destroyers;

every sea-mile gained towards the target without the alarm being raised would

be a triumph.

Assuming they made it to the narrows, they would then be

passing into the restricted throat of the estuary, less than two sea-miles from

their target, but with the full weight of Mecke’s three flak battalions ranged

close by them on either hand. These lighter, dual-purpose weapons of the 703rd,

705th and 809th Battalions, primarily 20 and 40mm, but with a sprinkling of

37s, would be able to switch quickly from air to surface targets, and COHQ’s

original concept of an approach by stealth had been constructed around the

premise that their crews must be far too busy firing skywards to worry about

the seaward approaches to the town.

Running past Korvettenkapitän Thiessen’s 703rd Battalion,

backed by the large searchlight ‘Blue 1’, they would come within easy range of

the defences both of the outer harbour and of the Pointe de Mindin on their

starboard beam, where were mounted the searchlights and 20mm cannon of Korvettenkapitän

Burhenne’s 809th Battalion. At this point, with the range so short, the

‘Charioteers’ would at least be able to reply in kind; however, they would also

be at their most vulnerable, which is why the air plan had been designed to

reach its crescendo during this period. Should the diversion succeed, then the

force just might reach the dockyard intact, at which point, while Campbeltown

raced for her caisson, the columns of MLs would break to port and make for

their own two landing points.

As leader of the formation, the gunboat, carrying Ryder,

Newman, Day, Terry, Holman and a handful of the HQ party, would circle to

starboard and support Campbeltown as she made her final dash. Only after she

was in place would Curtis put Newman’s party ashore in the Old Entrance. To

observe and record the gunboat’s subsequent peregrinations, Holman would remain

on board with Ryder.

In company with Curtis, and positioned at the head of either

column, the non-troop-carrying torpedo MLs, 160 and 270, were to make up a

small forward striking force on the way in, should enemy patrol craft be

encountered. While the landings were taking place, their job would also be to

draw fire and protect their fellow ‘B’s from interference.

Following ML 270 would be the troop-carrying MLs of the port

column, scheduled to land against the slipway on the northern face of the Old

Mole. Drawn from Wood’s 28th Flotilla, these were now under the direct command

of Platt in ML 447. As for the starboard column, sailing in behind ML 160,

Stephens’ ML 192 and the remaining three troop-carriers of his own 20th

Flotilla would lead the second pair of 7th Flotilla boats. Being torpedo-armed,

the latter two would have the secondary role of protecting the force from

rearward attack. All six boats in this column were to pass under Campbeltown’s

stern and put their men ashore in the Old Entrance.

Destined to play a crucial role in the coming action, both

as a primary landing point and as the position from which all retiring soldiers

were to attempt to withdraw, the Old Mole jutted some 130 metres into the

waters of the Loire. Standing twenty feet above the decks of the MLs, even at

the full height of the tide, it represented an obstacle which was almost

medieval in character – a fortress wall rising sheer from the water, which must

somehow be scaled, but from the top of which its defenders would prove almost

impossible to dislodge.

Strongly fortified by the Germans, its upper surface was

crowned by two substantial concrete emplacements, each more than a match for

the puny shells with which the ‘Chariot’ force would be obliged to attack them.

At its seaward end, a little to the rear of the lighthouse which marked its

furthest extension, was searchlight emplacement LS 21; about one third of the

way along was the 20mm gun position number 63, firing through embrasures and

all but impervious to attack. Not on the Mole itself, but situated close by its

landward end, and positioned so as to control the approaches to its northern

face, was the 40mm gun position number 62.

Protected by shallow water where it joined the quayside, the

Mole could be effectively attacked only by means of the long slipway running up

its northern face. At its tip, and giving access to the lighthouse, were tight,

narrow steps up which men might possibly scramble; however, they would then be

faced with a frontal attack on position 63. Placing scaling ladders against its

sheer stone face at some other point was always a possibility, but, with the

defenders able to direct fire downwards on to the decks of the boats, this

would surely be a tactic of last resort.

Always assuming they survived for long enough to reach the

Mole, a total of six MLs were briefed to put their Commando parties ashore at

the slipway, following each other in quick succession and then hauling off to

act in accordance with the orders of the Naval Piermaster, Lieutenant Verity,

RNVR. Designated Group One, and under the overall command of Captain Bertie

Hodgson, these parties, numbering a mere eighty-nine men, had the job of

overwhelming all the German defences in and around the Old Town and sealing the

area off by blowing up those bridges and lock-gates across the New Entrance by

means of which the Germans would surely seek to mount a counter-attack. Should

the Commandos succeed in this, then the Old Town area would be protected by

water on three sides, and by the Commandos of neighbouring groups on the

fourth, making it a secure base from which a successful withdrawal might later

be made.

Landing from Platt’s ML 447, the first party ashore was to

be Captain David Birney’s Assault Group ‘1F’, a heavily-armed fourteen-man

squad whose primary task was to capture and clear the Mole and establish a

bridgehead at its landward end. From this commanding position they could then

protect the remaining five MLs, initially as they came in to effect their

landings, and later as they sought to re-embark troops and return with them to

England. A small but important subsidiary task would involve clearing the

building containing gun position 62, so that it could be used as an RAP by the

two Commando doctors scheduled to land a short time later.

Following close upon the heels of Platt should be the ML of

Lieutenant Douglas Briault, carrying Assault Party ‘1E’, a second fourteen-man

unit, this time under the command of Bertie Hodgson himself. Also landing would

be Captain Mike Barling, the first of the Commando doctors, and two Medical

Orderlies, whose job it was to prepare to receive and treat the wounded.

Hodgson was to pass through Birney’s bridgehead and move south to capture and

secure the long East Jetty of the Avant Port, whose two gun positions, M60 and

M61, were able to fire into the flanks of any vessels approaching or leaving the

Mole. With the Avant Port secured, his party was then to picket and patrol the

built-up area of the Old Town itself.

The way having hopefully been cleared by the assault

parties, it would then be the turn of the demolition teams to land. First to

come ashore would be Group ‘1C’, landing from Collier’s ML 457 and consisting

of Lieutenant Philip Walton’s demolition team and their five-man protection

squad under Tiger Watson. Their job was to move quickly west towards target

group ‘D’ at the northern end of the New Entrance, where Walton and his party

of four would prepare the lifting bridge and lock-gate for demolition, while

Watson and his men watched over them like mother hens. In this exposed position

the men would be open to attack from several different quarters, despite which

demolition could not take place until all the other crossings had been

similarly prepared, as all the explosives were to be interconnected and fired

simultaneously. In overall charge of the demolitions within this sector was

Captain Bill Pritchard who, along with his small Control Party, would land with

Walton and Watson.

Next in line, and briefed to demolish the central lock-gate,

designated target ‘C’, would be the seven-man team of Captain Bradley, landing

from Wallis’s ML 307. This team would operate without a protection squad and

was to withdraw to the Mole immediately its work was done. Landing with them

would be Captain David Paton, the second of the Commando doctors staffing the

RAP; recording every detail for the Exchange Telegraph would be Edward Gilling.

Fifth to land, and carried on board ML 443, should be a

cluster of demolition parties charged with destroying the group of buildings

comprising target group ‘Z’. Consisting of three small teams under Lieutenants

Wilson and Bonvin, and Second-Lieutenant Paul Basset-Wilson, they would blow

the Boilerhouse, Impounding Station and Hydraulic Power Station. Landing with

them would be their protection party under Lieutenant Joe Houghton. Upon

completion of the work all three demolition parties were to withdraw to the

protection of Birney’s bridgehead.