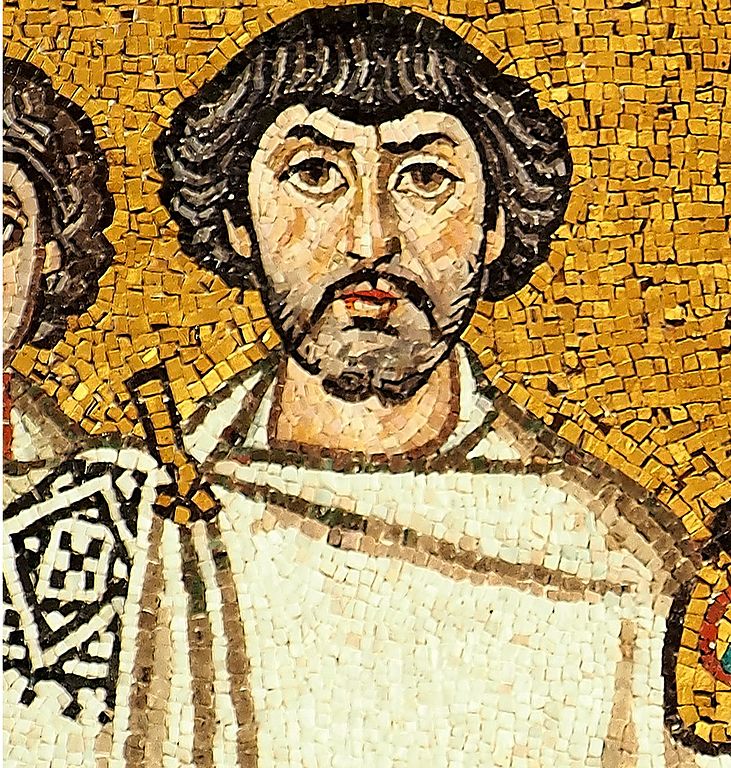

Belisarius may be this bearded figure on the right of

Emperor Justinian I in the mosaic in the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, which

celebrates the reconquest of Italy by the Roman army.

Late Roman/early Byzantine bucellarius. Belisarius’

household troopers would likely have looked much like this figure.

Map of the Byzantine-Persian frontier

Date obolum Belisaurio!

“Give an obol to Belisarius!” So a medieval fable spread

about the poor beggar who had once almost alone saved the Byzantine Empire and

helped ensure that it would endure for another nine hundred years.

More than a millennium after the exile, disgrace, and death

of Themistocles, the legendary general Flavius Belisarius in his old age was

supposed to have been reduced to a blind tramp, crying for coins in his

wretched state to common passersby along the streets of Constantinople. This

mythical end of the first man of Constantinople remained a popular morality

tale well into the nineteenth century. Romantic painters, poets, and novelists

all invoked the sad demise of Belisarius to remind us of the wages of

ingratitude and radical changes in fortune, which we are all, without

exception, prone to suffer. In Robert Graves’s novel Count Belisarius, the old

general is made to cry, “Alms, alms! Spare a copper for Belisarius! Spare a

copper for Belisarius who once scattered gold in these streets. Spare a copper

for Belisarius, good people of Constantinople! Alms, alms!

But even if a blind and mendicant aged Belisarius is a

mythical tradition, the general’s last years were tragic enough. After stopping

the Persian encroachment in the east (530–31), he saved his emperor from riot,

revolution, and a coup d’état at home (532). Next he recovered most of North

Africa from the Vandals (533–34). Then he directed, off and on, the invasion

and recovery of southern and central Italy from the Goths (534–48)—only to be

summarily recalled to Constantinople by his emperor Justinian. In all these

victories, either defeat or stalemate had seemed the most likely outcome.

Instead, the old Roman Empire of the Caesars was for a time nearly restored.

Then for the next decade (548–58), while war raged on all

the borders of Byzantium, the empire’s greatest general sat mostly idle.

Belisarius, for all his laurels, nearly disappears from the historical record,

as he was kept close at home by a suspicious and jealous emperor—worried that

the popularity of his victories might lead to a rival emperor rising in the

newly reconquered west.

As some sort of nominal senior counselor to the court of the

increasingly paranoid Justinian, Belisarius was to be kept distant from any

chance for more of the sort of conquest that had so enhanced his own

reputation—even if that exile might mean an end to the ongoing military

recovery of the Western Roman Empire abroad. But then suddenly, the general was

brought back out of retirement a final time to save the nearly defenseless

capital from a lightning strike of Bulgars under Zabergan in 559. His final

mission accomplished, Belisarius was dismissed from imperial service for good.

Stripped of honors, the old captain increasingly fell under court suspicion,

given his great wealth, his Mediterranean-wide fame, and his appeal among the

commoners of Constantinople.

By November 562, even his spouse, the aged court intriguer

Antonia—her legendary beauty long since dissipated—could not save her general’s

military career. He was in his late fifties. The general had not held a major

command abroad in twelve years since being replaced by the eunuch general

Narses in Italy. Justinian put the retired and worn-out Belisarius on trial for

his life on trumped-up charges of corruption and conspiracy to murder the

emperor, whom he had served so faithfully for most of his life. He was

imprisoned until found innocent in July 563. Thirty years of military service

that had saved both the emperor and his empire counted for almost nothing. His

once loyal former secretary and now hostile rival, Procopius, whose histories

are our best source of Belisarius at war in the east, North Africa, and in

Italy, may have been the court magistrate who oversaw his indictment and trial.

In any case, much of the later work of Procopius is hostile to the general whom

he once idolized.

While we need not believe ancient accounts that Belisarius

had been blinded and sat on display as a beggar, his last acquittal brought

little relief. The would-be restorer of Rome’s ancient glory died just two

years later, about sixty years old in 565—a few months before the end of his

octogenarian emperor, Justinian, who had done so much both to promote and to

ruin his career. For nearly the next fifteen hundred years, the strange odyssey

of Belisarius would serve as the theme of plays, novels, romances, poems, and

paintings. The renown was due in part to his central and exalted place in the

early chapters of the historian Procopius, an unbelievable career confirmed

elsewhere in other sources. The general’s victories, his serial arrests, and

his court ostracisms all made him a larger-than-life character.

At his death, Flavius Belisarius’ imperial

Constantinople—nearly wiped out by successive epidemics of bubonic plague, with

Bulgars once again nearing the gates of the city, its Christianity torn apart

by schisms and heresies, the great dome of the magnificent church of Hagia

Sophia just recently restored from sudden collapse due to design flaws, the

forty-year reign of its greatest emperor nearing a close—would nonetheless

endure another 888 years. Its resilience had been in no small part due to the

thirty-year nonstop warring of Belisarius—the last Roman general and the

greatest military commander that a millennium-long Byzantium would produce—who

in a brief three decades had expanded the size of the eastern empire by 45

percent. Belisarius did not save a theater, or even a war, but rather an entire

empire through unending conflict his entire life.

A Civilization in Crisis (A.D. 530)

When the inexperienced, twenty-five-year-old Flavius

Belisarius was first ordered eastward to Mesopotamia to preserve Byzantium’s

eastern borders from the Persian inroads, there was no assurance that an undermanned

and insolvent Constantinople would even survive in the east. Salvation was not

to be found in one or two battle victories against a host of enemies, but

rather in long, costly wars in which Byzantium slowly reestablished its

borders, assured potential aggressors that they would pay dearly for any future

invasions, and sought to reclaim rich western provinces long lost to various

barbarian tribes but critical to the original concept of Roman imperial defense

in the Mediterranean.

Far to the west, “Rome” by the early sixth century had

become no more than a myth. The Eternal City had been long before sacked by the

Visigoths (410), again by Vandals (455), and, two decades later, was occupied

(476) for a half century by the Gothic tribes. Almost all of Italy was reduced

to a Gothic kingdom, a thousand miles away from Constantinople in the east,

with tribal leaders squabbling over what wealth was left from a millennium of

civilization.

Visigoths had long reached and settled in the Iberian

Peninsula (475). Vandals—barbarians originally from the area of eastern Germany

and modern Poland—were recognized as the unassailable rulers of the former

Roman territory of North Africa (474). The Germanic Franks increasingly

consolidated their power in and around Gaul (509). For millions from northern

Britain to Libya, life was not as it had been just a century before. The Roman

army, Roman law, and Roman material culture west of Greece were all

vanishing—or at least changing in ways that would be unrecognizable to prior

generations. Newcomers from across the Rhine increasingly drew upon the

intellectual and material capital of centuries without commensurately

replenishing what was consumed.

The emperor Diocletian had for administrative purposes

divided the empire in the late third century A.D. In the early fourth century,

Constantine the Great had founded the eastern capital of Constantinople on the

Bosporus. Since then, Rome in the east had gradually developed a distinct

culture of its own. Latin gave way to Greek as the eastern empire’s official

language. The future Byzantium relied not so much on the fabled legions for its

salvation, but on its superb navy, and later on heavy mounted archers.

Constantinople looked more often eastward and southward to Asia and Africa for

its commerce and wealth. Unlike the west, the east had somehow survived the

fifth-century Germanic barbarian invasions from the north—perhaps given the

sparser enemy populations of the northern Balkans and the greater natural

obstacles offered by the Black Sea, Hellespont, and Danube.

Just as dangerous as foreign invasions were the multifarious

religious schisms and infighting among Christian sects. Heresies and orthodox

persecutions weakened resistance in the east to an insurgent Persia—and soon

enough Islam. Constantinople would grow to over half a million citizens. Yet

the empire’s enormous and costly civil service, and legions of Christian

clerics, often came at the expense of an eroding military. The administration

of God, the vast public bureaucracy, and the welfare state translated into ever

fewer Byzantines engaged in private enterprise, wealth creation, and the

defense of the realm—at precisely the time its enemies were growing in power

and audacity.

By the time of Belisarius, no more than 150,000 front-line

and reserve infantry and cavalry protected a six-hundred-year-old empire in the

east that, even shorn of its western provinces, still stretched from

Mesopotamia to the Adriatic in the west. If Italian yeomen had created the idea

of Rome that had spread to the Tigris and Nile, Greek speakers who never set

foot west of Greece kept it alive long after Latin speakers in Italy were

overrun by Goths. Byzantine power, shorn of much of its Roman origins, still

reached the banks of the Danube and the northern shore of the Black Sea and

extended to Egypt in the south. By strategic necessity, some seventy thousand

non-Greek-speaking “barbarians” were incorporated into the shrinking military.

The empire relied as much on bribes and marriage alliances as on its army to

keep the vast borders secure. Rarely has such a large domain been defended by

so few against so many enemies.

What ultimately kept the capital, Constantinople, safe were

its unmatched fortifications—the greatest investment in labor and capital of

the ancient world. And the legendary walls would prove unassailable to

besiegers until the sacking of the city by Western Europeans in the Fourth

Crusade (1204). Nearly as important was the Hellespont, the long, narrow strait

that allowed access from the Black Sea to the Aegean and Mediterranean and yet

proved a veritable moat across the invasion path of northern European tribes.

The well-fortified capital was surrounded by seas on three sides, and its navy

was usually able to keep most enemy invaders well clear of the city itself.

For all the problems of the Byzantines, the eastern empire’s

shrinking citizen body was still known as “Roman.” To moderns, Justinian’s

sixth-century Constantinople may seem corrupt and inefficient, set among a sea

of enemies with a declining population, and itself beset by faction and often

plague that would come to kill more than a million imperial subjects. But to

ancients, life within its borders by any benchmark of security and prosperity

of the times was far preferable to the alternatives outside.

The Visions of Justinian

Consequently, even without the reintegration of western

Europe and North Africa, Byzantium still controlled sizable territory

consisting of much of modern-day Greece, the major islands of the Aegean and

southeastern Mediterranean, the southern Balkans, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon,

Israel, Egypt, and Iraq. Within these borders, classical learning and

traditions of Roman law still ensured citizens ample supplies of pottery,

glass, building materials, food, and metals. Literacy remained widespread.

Thousands of imperial clerks and scholars continued to publish scientific and

philosophical treatises that both expanded classical scholarship and gave rise

to continually improving agriculture, military science, and construction.

Scholars have sometimes questioned whether Christianity—not

just porous borders, Germanic tribes, punitive taxation, endemic corruption,

inflation and debt, and constant civil strife—led to the fall of the Roman

Empire in the west. Had Christian ideas of magnanimity and pacifism replaced

classical civic militarism, while hundreds of thousands of otherwise productive

soldiers and business people flocked to religious orders? The theory of

Christian-caused decline, however, would fail to account for a near-millennium

of continued rule in the Christian east well after the fifth century A.D. loss

of the Roman west. Instead, in the eyes of Romans at Constantinople, belief in

the Christian God had at last given their existence meaning and renewed

determination to preserve their culture amid the collapse of Mediterranean

Rome. The more the Eastern church was both beleaguered and persisted, the more

its unassailable orthodoxy was considered critical to Byzantium’s survival.

For a few visionaries like the future emperor Justinian and

his lieutenant the young Belisarius, a tottering Byzantium should be not only

saved but at all costs expanded. We do not know the degree to which Justinian

from the beginning had systematic plans of restoring the lost western empire,

or whether his successes in North Africa and Sicily led opportunistically to

more ambitions in Italy in ad hoc fashion. Eastern Romans, in spite of their

schisms and heresies, still believed that they had avoided much of the civil

strife so destructive in the west. Byzantines had the more defensible borders,

and a far more secure capital protected by massive walls and water on three

sides, and so they, in time, could reconstitute much of the original domain of

Augustus—or so at some point the young emperor Justinian may have begun to

dream. That most residents of sixth-century North Africa and Italy might well

have preferred to have been ruled by Vandals and Gothic tribes rather than see

their lands devastated and depopulated for years in a war brought on by

long-forgotten Greek-speaking foreigners was largely irrelevant to Justinian.

Belisarius was to become rich from the spoils of his western

conquests. He no doubt enjoyed the laurels of victory and the fame his military

prowess ensured. But ultimately what drove him and thousands in the high

echelons of Byzantine government and the military for more than thirty years

against near impossible odds were both his faith in Christianity and his

allegiance to the idea of Roman civilization and the gifts it had bestowed on

millions. In other words, the generation of Belisarius fought relentlessly to

reclaim the old empire because it believed in the idea of Rome—because it felt

the restoration of the old way to be far better for their would-be subjects

than the present alternative.

Belisarius under the walls of Rome

Flavius Belisarius the Thracian (505–27)

Little is known of Belisarius’ early life before his entry

onto the pages of Procopius’ history. He first appears already a young officer

in the imperial guard of the future emperor Justinian headed into Armenia with

an army—“young and with first beard.” In a striking mosaic panel in the

sixth-century church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (built not long after

Belisarius captured the city), Belisarius, in simple civilian dress, appears to

the right of his emperor Justinian. He stares out as a thin, dark-bearded young

man of about forty, with thick, carefully combed black hair. The mosaic

suggests more a scholar than a warrior.

In any case, Belisarius was born in ancient Thrace in what

is now western Bulgaria, sometime between A.D. 500 and 505. He was in his early

to midtwenties when Justinian became emperor and had previously served the

future ruler in his personal guard.12 Although the two would soon be at odds,

there was some personal affinity between them that might explain why the young

twentysomething officer, with little frontier experience, was sent out with an

army to the eastern border to quell a Persian attack on the far reaches of the

empire. Given his age, the relatively small size of his forces, and his lack of

any experience fighting seasoned Persian troops, it is a wonder that the young

Belisarius survived the frontier at all.

Both Justinian and Belisarius married powerful

women—Theodora and Antonia respectively. Both wives’ pasts were of supposed ill

repute. That fact is often cited as explaining the inordinate influence that

the two women held over their husbands, in a fashion atypical even of the

lively early Byzantine court. Justinian and Belisarius were also both Thracians

by birth. Unlike most Byzantine elites, they were native Latin, rather than

Greek, speakers. These affinities also may explain why both would share the

notion that the lost distant western provinces and the old capital at Rome were

key to Byzantium and could still be brought back inside the empire. But for

such a grand notion to become reality, a shaky and nearly insolvent

Constantinople would first have to ensure security on its perpetually contested

eastern borders with Persia.

Belisarius Goes East: The First War Against the Persians

(527–31)

On the eastern borderlands—roughly in parts of modern-day

western Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and eastern Turkey—the horsemen

of the rival Sassanid Empire of Persia continually pressed the empire. Even in

classical times, Caesar’s Rome had been unable to pacify the Arab and Persian

east in any permanent manner. Some of Rome’s greatest losses—the deaths or

capture of nearly thirty thousand legionaries at Carrhae (53 B.C.) and Mark

Antony’s serial defeats in the east (40–33 B.C.)—were at the hands of Parthian

and later Persian armies. In general, due to the problems of land transport,

scarce water, and great distances from the Mediterranean and Aegean, Romans

preferred to work out general agreements with the Persians. These accords left

much of the eastern frontier with only vaguely demarcated borders, along a line

descending from the southeastern shores of the Black Sea nearly down to the Red

Sea.

Court accountants at Constantinople carefully calibrated the

relative expenses of appeasement versus military action. They usually concluded

that it was cheaper to pay an Iranian monarch to stay eastward than to march

out eight hundred miles from Constantinople to stop him with an army. In any

case, both Iranians and Byzantines had plenty of other enemies, and so in time

they grudgingly acknowledged each other’s civilizations; and they found their

arrangements mutually acceptable for decades. But in 527 the Persian monarch

Kavadh and the dying Roman emperor Justin dropped the old protocols of

understanding. Kavadh claimed Justin had reneged on ceremonially adopting his

son Chosroes (Khosrau) to cement a closer alliance. Justin, in turn, had tired

of paying the bribe money and thought resistance to Persian demands could for

once prove cheaper than the serial gold payouts.

In reaction to the increasing tension, the Persians attacked

the pro-Byzantine region of Lazica on the Black Sea. That aggression prompted a

retaliatory strike against Persia—if a slow-moving expedition could be so

called—by the emperor. War was on. A series of expeditions went eastward, among

them a northern corps led by the young, untried Belisarius and his

co-commander, Sittas. The historian Procopius at the time explained the unusual

promotion of someone so young to high military office by the fact that the

hitherto obscure Belisarius was attached to the imperial guard of the general

Justinian, nephew to the emperor Justin (518–27) and probable heir to the

throne. He had surely not earned command by any prior feat of arms. The young

Belisarius found himself in a near-hopeless war, far from home against far more

experienced and numerically superior enemies.

At first Belisarius and Sittas, under the general command of

Justinian, had mixed success along the frontier in Persarmenia, ravaging enemy

territory before losing a pitched battle to the Persians. In just this first

year of operations, the inexperienced Belisarius had done well enough to be in

position as a commander to take advantage of two unexpected events. First, the

other Byzantine generals, Belisarius’ rivals, had fared even more poorly—or

perished. Libelairus (the magister utriusque militum, or overall theater

commander of infantry and cavalry) lost his nerve on hearing of the Byzantine

setback in Persarmenia. He then retreated from an attack in the south at

Nisbis, and thereby gave up his command. Then the regional commander in eastern

Turkey and Iraq (dux Mesopotamiae), Timostratus, died. For unknown reasons,

Sittas, not Belisarius, was probably blamed for the initial failure in

Persarmenia. The result was that Belisarius replaced Timostratus and took over

overall command of efforts at expanding operations to the south in Mesopotamia

Second, in August 527, the emperor Justin died. Belisarius’

patron, Justinian, at last assumed power. The Byzantines committed far more

resources to the Persian war, including a plan to build an extensive system of

border forts and defenses to keep the Persians out of Roman territory. Again,

Constantinople had neither the resources nor the desire to invade Persia, much

less to topple the Sassanids. Instead, its limited aims were occasional hot

pursuit across a new fortified line that might achieve some sort of deterrence

and so bring an uneasy peace in the east without the costly bribes. The

resulting savings would supposedly allow the funding of more important

impending operations in the west, where most of the old Roman Empire had been

lost.

Yet neither Justin nor his successor, Justinian, had yet

quite conceded that the protection of the old eastern border with Persia—given

the loss of resources from the Roman west—was beyond the power of their meager

forces. The fact was that the grand strategy of the new young emperor

Justinian—the notion of waging an eastern war to allow a subsequent, far more

ambitious conflict to begin against the Vandals in the west—was courting

disaster. The burden of two-front operations, from Gibraltar to the Euphrates,

would plague all subsequent operations over the next twenty years. As Napoleon

learned in 1812, and the Germans discovered in 1944, distant dormant fronts to

the rear have a habit of awakening at inopportune moments to plague a

bogged-down invader with multifarious battles.

Still, young Belisarius almost immediately proved worthy of

his selection through two characteristics that would elevate his leadership

above his contemporaries. First, he was calm in battle, and he knew

instinctively the relationship between tactics and strategy and thus avoided

wasting the limited resources of the empire in needless head-on confrontations

that would lead to no long-term advantage. Second, Belisarius was skilled in

counterinsurgency, in winning the hearts and minds of local populations by not

plundering or destroying villages and infra-structure—an advantage in the dirty

wars fought in the vast no-man’s-land between Persia and Byzantium. Such

restraint was rare among gold-hungry Byzantine commanders in the east. The

result was that, even after initial defeats, Belisarius never lost an army or

had hostile populations turn on his rear.

At Mindouos, the Byzantines under a joint command were

repulsed when they rashly advanced and got entangled in concealed Persian

trenches. The other commanders, Bouzes and Coutzes especially, were faulted for

the defeat, while Belisarius managed to retreat with most of the cavalry

intact. In subsequent efforts to fortify Mindouos, Belisarius was again

defeated. He was forced to withdraw to the fort at Dara. Yet he was rewarded

with promotion and immediately began retraining an army in expectation of a

renewed Persian offensive. The Byzantines had lost a series of battles, but

their forces had forfeited little territory and were still largely intact.

Progress continued on their fortifying lines. And now a battle-tested

Belisarius enjoyed authority over rival commanders.

Then at Dara in 530, along with his co-commander Hermogenes,

Belisarius marshaled some twenty-five thousand troops against Persian forces at

least twice that size. He was determined to decide matters through pitched

battle. He had learned much from his previous defeats; this time, the

commanders ordered their troops to construct elaborate trenches in front of

their formations. They positioned infantry provocatively to the front and

center, ahead of the cavalry on the wings—but reinforced at its rear with

additional concealed horsemen. Belisarius figured that the enemy would be

impeded by the trenches and confused by foot soldiers deployed so brazenly at

his front. Perhaps the Persians would then slough off from his strong center to

attack the wings instead. That way, as the enemy advanced and began to spread

out, Byzantine cavalry, and hidden reinforcements behind the infantry, could swarm

the enemy on its flanks.

After an initial two days of skirmishing and futile

negotiations, the battle began in earnest on the third day. The Persians added

another ten thousand reinforcements. Belisarius had removed a cavalry

contingent from his left wing and positioned it farther to the rear, hidden

behind a small hill. When the Persians attacked on the right, they were

surprised on both sides by the secondary mounted forces of the Byzantines. Over

on the opposite side, the backpedaling infantry and cavalry on the Byzantine

left held long enough for their mounted reserves to similarly hit the Persians

on the flank.

Some five thousand elite mounted Persians were killed in

just a few hours. In response, the less reliable Persian infantry in the center

threw down their arms and retreated. Altogether, more than eight thousand

Persian horse and foot soldiers were lost. A Byzantine expeditionary force—for

the first time in memory—had defeated a massive Persian army in the east, and

one nearly double its own size. The dramatic win at Dara gave the Byzantines a

respite until the next spring, 531, when on Easter Day they met the Persians

again to the south on the northern bank of the Euphrates River. Unfortunately,

the lessons from Dara were not fully digested. Buoyed by the success at their

prior victory, Belisarius’ co-commanders believed that they no longer needed

fixed positions, impediments and trenches, or the use of deception to defeat

the Persians. Now, after Dara, they fooled themselves into thinking that the

Byzantines were innately superior and could fight much more mobile Persian

forces on almost any terrain and at any time they wished.

The result was disaster at the ensuing battle at Callinicum,

fought on the banks of the Euphrates on April 19, 531, in what is now northern

Iraq. With five thousand Ghassinid Arab cavalry and twenty thousand imperial

troops, Belisarius recrossed the Euphrates and for once had a temporary

numerical advantage over a Persian army of about fifteen to twenty thousand. But

the enemy was mostly mounted and mobile, and the Byzantines were recklessly

intent on pursuing the enemy.