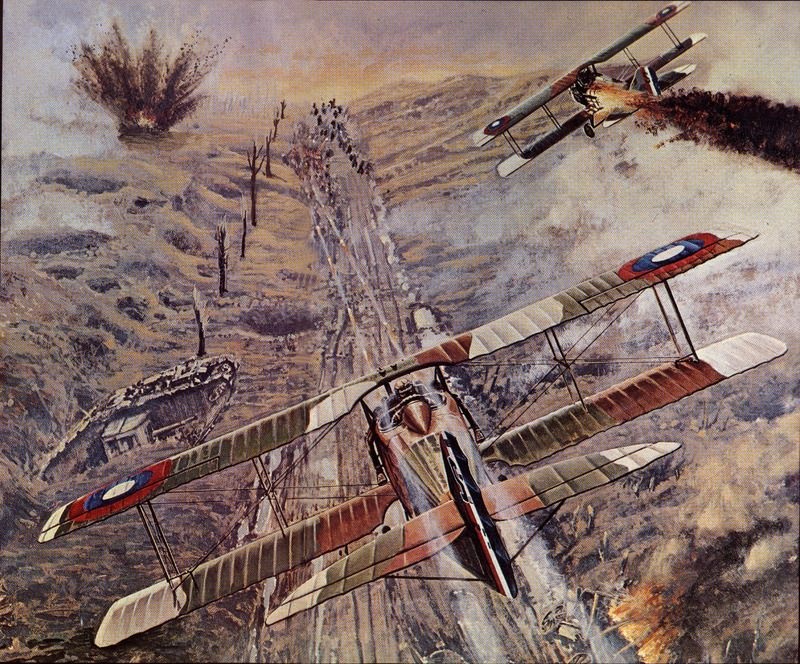

Two American Spads strafe German troops during the St.

Mihiel battle; one of them is hit by ground fire by Robert W. Wilson.

Fokker DVII, on Strafing Run over Trenches by Michael

Turner

In Meuse-Argonne action of late September and on, American

pursuit and observation units reported ground machine-gunning as regular work.

In more specific terms the citation for award of the Silver Star to an American

pilot for strafing a German artillery unit read in part, for “killing 60

horses and a like number of men.”

The U. S. 1st Pursuit Group flew numerous low-altitude

patrols to counter German squadrons of specialized ground attack aircraft,

called “troop strafers” by American troops. Flying under 500 feet,

our pursuits broke up numerous such attacks. But these heavily gunned and

armored enemy planes also caused Gen. Pershing, commander of the American

Expeditionary Forces, to state a need to Washington for a larger caliber,

higher muzzle velocity aircraft machine gun to best shoot them down.

A specialized U. S. air unit was the 185th Aero Squadron,

flying Camel pursuits. It was trained to engage German Gotha bombers operating

at night. Yet, when bad weather frequently halted these German raids, the 185th

turned to low-level night attack of the enemy on the ground. On one mission a

German train was strafed as it steamed along unsuspecting of such attack at

night. Also, staff officers of Brig. Gen. Mitchell, driving at night with

lights on, took hits in their vehicle by machine-gun fire from a German

aircraft above.

Some of the under-lying principles and nature of that

“doing” came directly from World War I strafing. For example, in the

film and video Thunderbolt (sponsored by the U. S. Army Air Forces [USAAF]) on

World War II air action, P-47 pilots are shown shooting up trucks, trains and

other targets of opportunity with their aircraft machine guns in Italy in 1944.

As the narration states, “Every man his own general!” Found in a film

production, these words may hint at “theatrical,” but they are fully

valid historically.

Examples of British, German, and American strafing show

varied missions flown. Lt. Case was on a 14-plane mission. Rickenbacker and

Chambers operated as a pair. MacArthur and Udet flew one-man efforts. But

regardless of how many planes left home base together, once into strafing

action it was done as single planes or small elements-and those pilots and

element leaders became the decision makers in their searches for and attack of

targets, now their own generals.

But that is not the full story. We need to identify just

what was being employed in this air-to-ground machine gunning as these

decisions were made. Was it planes and aircrews, and guns and ammunition? Yes,

but more specifically and accurately from the pilot’s and aircrew’s view, it

was the “time of fire” of the guns. That time of fire was inherent in

gunfighting. It was there in some amount of time, continuously available for

use on the enemy. On the other hand, that time of fire could not be used all at

once. It took that long to generate it-as opposed to bombs, rockets, etc., that

could be released all at once or almost so if desired. Thus aircraft

gunfighting (dogfighting and strafing) had a built-in decision factor for

pilots and aircrews in applying its time of fire. For strafing, whether trench

strafing, ground strafing, airfield strafing, or hunt and find strafing, once

out over the enemy there was always that amount of time up for decision on how

to use it.

With his time of fire, Lt. Mayberry moved about strafing a

variety of targets. So did Case. Udet stayed in one place with repeated passes

to destroy a key target there. MacArthur went back mission after mission, pass

after pass, to shoot troops crossing a river. Rickenbacker and Chambers stayed

with their large convoy target, as did the Allied strafers who destroyed 11 new

Fokkers on an airfield. Young and Bogel and Richthofen were not even on

strafing missions; they just decided to strafe.

The majority of the pilots and aircrews in these examples

used all their firing time, applying it in multiple passes. In every case, they

had a specific target that they had found. Their shooting was aimed right into

that in-view target. They wasted little or none of their time of fire toward

anything except bullet holes in enemy equipment and hides. That maximum number

of such holes per airplane employed seems a very valid and effective

concentration of force and firepower on the enemy-even though the warriors

doing it were spread out in small numbers at the time.

Then, too, the capabilities and characteristics of aircraft

and guns demanded on-the-spot decisions for the situation in each pass. The

best pursuit planes of World War I had top speeds of around 130 miles per hour.

Thus strafing passes ranged from diving speeds above that to much slower in

early war pursuits. However, one fact about speed and flight attitude, (which

is not obvious to many people) is that fixed forward-firing aircraft guns could

be fired regardless of how fast or slow they were flown, or whether flown

straight down, some lesser dive, or flat, or with wings level, in a bank, or

even inverted. The guns fired wherever they pointed when the trigger was

pulled.

Thus strafing did not require tables of speed, altitude,

dive angle, and the like from which to plan attacks then closely execute in

order to achieve accuracy. The pilot was free to aim the guns in anyway desired

or needed. To concentrate bullet impacts on a target, the aircraft nose was

held on it while firing, usually requiring some degree of “dive” to

do so. To spread bullets along or throughout an area on the ground, the

aircraft nose was made, or allowed, to move while firing.

Lt. Mayberry flew near level on the deck in order to aim his

guns into the open ends of sheds housing enemy planes. To aim those same guns

on the troop train among buildings in town, he had to dive down from above to

have an unobstructed line of fire. Lt. Case stressed he “dived” to

hold his gunfire on troops at the door. Rickenbacker and Chambers

“porpoised” down an enemy column. Had they flown along level above

it, their guns would never have pointed down on it. A steep dive was necessary

to shoot downward on troops in trenches. Yet, shallower dives were more common

on troops in the open and numerous other targets. There was an endless variety

of target situations.

References report that World War I pilots felt that certain

altitudes were very dangerous in strafing passes, particularly 300 to 500 feet.

Starting higher, 1,000 to 1,500 feet was considered best; then when pulling out

down low, 100 feet or on the deck, to stay down in leaving the target area. It

can be assumed that was a desirable pass. But the examples vary greatly from

it. They show passes flown as needed and chosen to achieve effective results on

particular targets and also for repeat runs, and strafing under weather of low

ceilings of 500 feet and below-with many passes made entirely in the highest

danger zones-all decided by pilots in the air to accomplish the mission.

Certainly there were numerous other factors, including equipment as well as

flying and aiming techniques, involved in decisions, and these are primary

subjects of later chapters. But recognition of this underlying great flexibility

in use of fixed, forward-firing aircraft guns from this war is felt to be

essential back- ground to those chapters.

Flexible guns of rear-seat and other aircrew gunners had

their story too. Primarily for rear arc protection against enemy aircraft, examples

show much of their strafing was done in that rear arc as the aircraft passed

over and beyond a target. But they also had a capability unique to them. A

pilot could bank the plane and circle above a target while the gunner fired

downward on the inside of the turn to concentrate fire on that target; and he

could hold it there on target as long as the plane circled above.

The German specialized ground attack planes had

forward-firing and flexible guns and, in certain cases, downward-firing guns

mounted in the fuselage. However, if these “downward” guns were fixed

position or limited in fore and aft traverse, bullets would always impact along

the ground in raking or “walking” fire; a gun had no real capability

to aim on a specific target. This type fire was useful in places, and pursuit

pilots at times “walked” bullets too. But downward-mounted guns were

one element of World War I strafing that did not go on to standard use in

future wars (although some slightly depressed guns have been used).

Summaries on American strafing in The U. S. Air Services in

World War I include the following: “[T]he enemy’s troops were attacked by

our pursuit air- planes with machine guns and bombs…. [T]his aid from the sky

in assisting during an attack by our troops or in repelling an attack or

counterattack by the enemy greatly raises the morale of our own forces and much

hampers the enemy. It will be well to specialize in this branch of

aviation.” Thus there was postwar high-level recognition of the

contribution and value of strafing, where prewar judgment of it had been

“absurd.” However, that recognition was in broad military terms,

without publicity on strafers and their accomplishments.

Maj. Hartley had said he would dearly love to know just what

damage MacArthur did in a single day. Since Hartley did not know, it is

unlikely the world will ever know either. A citation noted one pilot killed

sixty horses and a like number of men on a mission, but no figures are found

for how many he killed in the entire war, nor of accumulated scores of damage

done by other individual strafers during World War I. Of the names in examples

covered, only those of the top aces, with their confirmed scores of air

victories, are known to the public. The “unknown” names mentioned

here are not even a token of the total strafers in the war. Yet, examples leave

no doubt that their duty, valor and sacrifice ranks with the greatest in all

history. This is certainly the ultimate story and legacy passed on by these

pioneers, and it is a legacy of honor ingrained in and inseparable from the

strafing of later wars.

It is fact that strafing was a pilot and aircrew creation

from which they set the way in utility and tackled varied targets, situations

and weather, much done voluntarily. This established strafing as a “pilot

and aircrew and cockpit” business. Expertise in and conduct of strafing

operations, and the knowledge thereof, was from the start, and remains, located

at combat unit level, not at high headquarters, schools, and archives. Strafers

are largely their own generals in this respect, too.

No books dedicated to World War I “strafing” have

been written. The examples here are based on material in books on “aces

and fighter planes,” including Von Richthofen and the “Flying

Circus” by H. J. Nowarra and Kimbrough S. Brown; Rise of the Fighter

Aircraft, 1914-1918, by Richard P. Hallion. These volumes on aces and fighters

include much on strafing; yet, they do not mention “strafing” or

“strafers” in titles, nor in most cases in tables of content. The

same is true for general histories and other accounts of that war and sub-

sequent wars.