Syrian combat performance in Lebanon showed improvement over

past wars in some respects, while in other ways it showed no improvement

whatsoever.

Strategic Performance.

Given the conditions under which they were forced to

operate—and despite Asad’s continued commissarist politicization of his armed

forces—Syrian generalship was fine, even good, although not brilliant. Syrian

moves in the first few days were wise given their desire to avoid provoking

Israel while preventing the IDF from securing a decisive advantage and then

attacking the Syrian forces in Lebanon. Syrian units were placed on alert right

away and ordered to begin preparing and repairing defensive positions along key

axes of advance. Damascus bolstered its air defenses in the Bekaa and

redeployed two of its best armored divisions plus several more commando

battalions to reinforce its units in Lebanon, many of which had been on

occupation duties for so long that they were not combat ready.

When the Israelis began pushing up the spine of the Lebanon

range toward the Beirut-Damascus highway, the Syrians recognized the danger of

this move and decided to block it, regardless of the potential for provoking a

war with Israel. This too was probably the right move: as badly as the fighting

in the Bekaa actually went for Syria, it almost certainly would have been worse

had the Israelis been able to cut the Beirut-Damascus highway and then attack

into the Bekaa from behind the main Syrian defense lines.

Syria’s strategy for fighting the Israelis once it became

clear that war was unavoidable was also reasonable. Damascus deployed its

commandos forward with armor support in ambushes along the narrow paths into

the Bekaa. They were ideally placed to contest the Israeli advance. The

alternative, deploying all of the commandos with the reinforced 1st Armored

Division along the main Syrian defense lines in the Bekaa, would not have taken

full advantage of the commandos’ capabilities, and their impact would have been

diminished.

The Syrian defensive strategy in the Bekaa was

straightforward: a standard, Soviet-style defense-in-depth with two brigades up

and one back, but entirely appropriate for the situation. It may be the case

that a truly brilliant general might have found a better approach, but the

Syrian strategy was not bad, and it is unclear that Syrian tactical forces could

have implemented a more sophisticated defensive scheme. For instance, any kind

of elastic defense strategy would have given up the enormous advantage of the

terrain. It also would have required Syrian units to prevail over the IDF in

fluid maneuver warfare. Given the drubbing the Syrians took when they were

defending in place and had all of the advantages of the terrain, and how badly

their forces fared when they tried to maneuver against the Israelis, it seems

likely that any such mobile defense would have failed far worse.

Finally, although the decision to commit the Syrian Air Force

to defend the SAMs and the ground forces in the Bekaa Valley resulted in the

destruction of about a quarter of the Syrian Air Force, it too was probably the

best move. Not sending out the Air Force to confront the Israelis would have

been a severe blow to morale throughout the Syrian armed forces. Moreover, the

Syrian Air Force did succeed in keeping much of the Israeli Air Force occupied

on June 9–10, the key days of the battle. In fact, the IAF was so intent on

killing Syrian MiGs that they concentrated most of their effort on the air

battles. As a result, the IAF did not provide much support to Israeli armor in

the Bekaa until late on June 10 when the Syrian lines had already been broken.

Of course, what can be faulted in the decision to commit the Syrian Air Force

was the absence of any real strategy that took into account the well-known

shortcomings of Syrian planes and pilots and so might have allowed the Syrian

fighters to accomplish something more than merely serving as a punching bag for

the IAF to distract it from the ground battles.

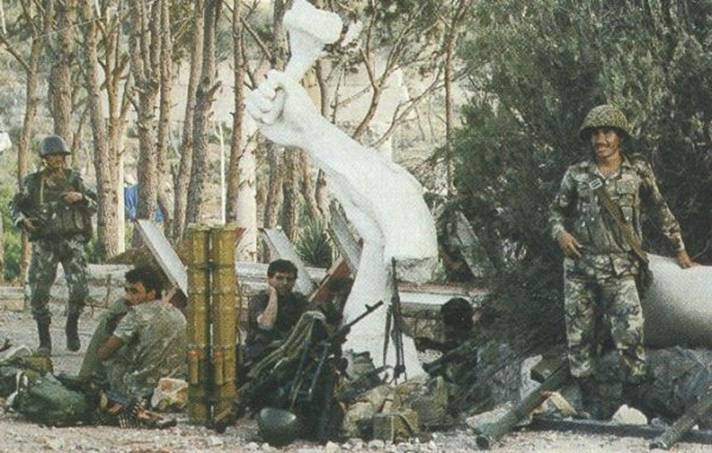

Tactical Performance. The real variations in Syrian

military effectiveness were at the tactical level. Specifically, there was a sizable

gap between the performance of Syrian commandos and that of the rest of the armed

forces. Syria’s commando forces consistently fought markedly better than any

other units of the Syrian military. They chose good ambush sites and generally

established clever traps to lure the Israelis into prepared kill zones. The

commandos showed a decent ability to operate in conjunction with tanks and

other armored vehicles, integrating them into their own fire schemes and doing

a good job protecting the tanks from Israeli infantry. The Syrian commandos

also were noticeably more aggressive, creative, and willing to take initiative

and to seize fleeting opportunities than other Syrian units. Their surprise

counterattacks on Israeli armored columns at Ayn Zhaltah and Rashayyah in the

Bekaa stand out in particular. Finally, the Syrian commandos did an excellent

job disengaging whenever the Israelis began to gain the upper hand in a fight,

at which point they usually pulled back to another ambush site farther up the

road.

In contrast, the rest of Syria’s armed forces performed very

poorly, manifesting all of the same problems that had plagued them in their

previous wars. In the words of Major General Amir Drori, the overall commander

of the Israeli invasion, “The Syrians did everything slower and worse than we

expected.” Without a doubt, the Syrian Air Force performed worst of all the

services, but having discussed their problems in some detail above, I will

concentrate on the Syrian Army.

As opposed to the competent performance turned in by their

commandos, Syria’s line formations had little to brag about other than their

stubborn resistance and orderly retreat. Syrian armor consistently refused to

maneuver against the Israelis, with the result that in every tank duel, no

matter how much the terrain or circumstances favored the Syrians, it was only a

matter of time before the Israelis’ superior marksmanship and constant efforts

to maneuver for advantage led to a Syrian defeat. Chaim Herzog has echoed this

assessment, observing that the Syrian military’s greatest problem was its

chronic “inflexibility in maneuver.” Syrian artillery support was very poor and

had little effect on the fighting. Syrian artillery batteries showed almost no

ability to shift fire in response to changing tactical situations or to

coordinate fire from geographically dispersed units. Syrian armored and

mechanized formations recognized the need to conduct combined arms operations,

but showed little understanding of how to actually do so. Infantry, armor, and

artillery all failed to provide each other with adequate support, allowing the

Israelis to defeat each in detail. In general, the Syrians relied on mass to

compensate for their tactical shortcomings, but Israeli tactical skill proved

so overwhelming that even where Syrian armored and mechanized formations were

able to create favorable odds ratios, they were still easily defeated by the

Israelis.

Damascus’s ground forces had other problems as well. Syrian

units were extremely negligent in gathering information and conducting

reconnaissance. Many Syrian commanders simply failed to order patrols to keep

abreast of Israeli movements in their sector, instead relying on information

passed down from higher echelons. Those patrols that were dispatched seemed to

have little feel for the purpose of reconnaissance and rarely gathered much useful

information. As a result, many Syrian units blundered around Lebanon with

little understanding of where the Israelis were, sometimes with fatal

consequences. Syrian units showed poor fire discipline, squandering rounds so

quickly that they were forced to retreat because they were out of ammunition.

Despite extensive training in night-combat from their Soviet advisors, Syrian

units were almost helpless after dark. Syrian personnel at all levels could not

night navigate, their units lost all cohesion in the darkness, and morale

dropped accordingly. Only some of the commando units showed any ability to

actually apply the training they had received and operate after dark but,

fortunately for the Syrians, the Israelis generally halted each night.

The Syrian Gazelle helicopter gunships made a huge

psychological impact on the Israelis, but did little actual damage. The

Gazelles were not able to manage more than a few armor kills during the war,

and although they employed proper “pop-up” tactics, they could only delay the

Israelis. Although this was useful in slowing the Israeli advance to the Bekaa

and then hindering the Israeli pursuit after they had broken through the Syrian

lines, the Gazelles were unable to prevent Syrian defeats, even when they were

committed in large numbers as in the fighting around Lake Qir’awn. One Israeli

officer observed that the Syrian Gazelles were “not a problem” because they did

not employ them creatively, had bad aim, and operated only individually or in

pairs, making it easy for the IDF to handle them. Anthony Cordesman has

commented that Syrian helicopter operations in Lebanon suffered from “The same

tactical and operational rigidities, training, and command problems that

affected its tank, other armor, and artillery performance.” Consequently, their

contributions were negligible.

Syrian combat support was another impediment to their

tactical performance. In particular, Syrian logistics were appalling. Damascus

had established huge stockpiles of spares and combat consumables in the Bekaa,

yet during the combat operations many Syrian units could not get resupplied

(although part of the problem was their wasteful expenditure of ammunition).

Graft had riddled the Syrian quartermaster corps with the result that a lot of

things that were supposed to have been available were not. In addition, the

Syrians did not understand their Soviet-style “push” logistics system, with

quartermasters demanding formal requests for provisions, rather than simply

sending supplies to the front at regular intervals as intended.

Maintenance was another problem area for the Syrians. Most

Syrian soldiers were incapable and unwilling to perform even basic preventive

maintenance on their weapons and vehicles. Instead, these functions had to be

performed by specialized technicians attached at brigade and division level,

and for most repairs, equipment had to be sent back to a small number of

central depots around Damascus. These facilities were manned in part by Cuban

technicians who handled the more advanced Soviet weaponry. The Israelis

reported capturing a fair number of Syrian armored vehicles abandoned because

of minor mechanical problems.

The fact that Syria’s commandos performed so much better

than Syrian units ever had in the past should not obscure the fact that, in an

absolute sense, when compared to the forces of other armies, Syria’s commando

battalions were still mediocre. In general, the Syrian commandos were content

to sit in their prepared positions, fire down on Israeli forces that wandered into

their ambushes, and then retreat as soon as the Israelis recovered and began to

bust up the Syrian defensive scheme. Incidents such as the commando

counterattacks at Ayn Zhaltah, Rashayyah, and a few other minor engagements

were still exceptions to the rule. They are noteworthy because they were among

the only times that even the commandos tried to get out and upset Israeli

operations. The rule, however, was for the commandos to establish ambushes and

then wait passively for the IDF to come to them.

The commandos also weren’t terrific with their weapons: on

any number of occasions, Israeli units were completely trapped by Syrian

commando ambushes, and subjected to a hail of gunfire, grenades, and missiles,

only to emerge having suffered just a handful of casualties. In addition, like

other Syrian formations, the commandos frequently neglected to cover their

flanks or were too quick to conclude that terrain was impassable. As a result,

many Syrian ambushes were cleared by Israeli flank guards or bypassed altogether

when Israeli combat engineers found a way through terrain the Syrians had

deemed impassable.

Unit cohesion among Syrian formations in Lebanon was

actually quite good. For the most part, Syrian units stuck together and fought

back under all circumstances. Few Syrian units simply disintegrated in combat.

The rule was that Syrian units fought hard and then stuck together and

retreated well. Although it is true that Israeli pressure was

uncharacteristically light on the Syrian armored forces withdrawing up the

Bekaa after their defeat on June 10, there were still many instances of Syrian

units showing good discipline and retreating in good order under heavy

pressure. The commandos in particular showed outstanding unit cohesion. In many

fights they clung to their defensive positions until they were overpowered by

Israeli infantry units, and in several clashes, Syrian commando units fought to

the last man to hold particularly important positions or when acting as rear

guards to allow other forces to escape.

Syrian Combat Performance and Underdevelopment

It’s easy to get distracted by the better performance of

Syria’s commandos in 1982 and see it as evidence that the Syrians had improved

dramatically over their performance in 1948 (and 1967, 1970, 1973, and 1976).

It’s just as important not to. The commandos represented no more than about 5

percent of the Syrian forces that fought against the Israelis in Lebanon. They

were better than the other 95 percent, but not dramatically so. They never

proved the equal of their Israeli opponents. They were always beaten, sometimes

badly, sometimes very badly.

Meanwhile, the rest of the force was pretty disastrous and

showed no marked improvement over the conduct of their predecessors back in

1948. It’s not that there weren’t any differences between the Syrian Army of

1948 and that of 1982. There were. And in some important areas and in some very

noticeable ways. But overall, it’s hard to make the case that Syrian combat

effectiveness had improved much.

Syrian strategic performance was notably better in 1982 than

it had been in 1948, but that had nothing to do with underdevelopment. If

anything, it is another bit of evidence regarding the impact of politicization.

Asad had found a handful of generals who were both competent and loyal to

command his forces before the October War, and these men largely remained in

charge in 1982.

Syrian tactical leadership, however, demonstrated the same set

of problems that plagued their forces in 1948 and all of the wars in-between.

Their junior officers would not act aggressively or creatively, could not

execute ad hoc operations, did not bother to patrol or otherwise try to collect

information, could not maneuver for advantage or even shift their forces to

react to enemy maneuvers. They rarely counterattacked, and when they did so it

was generally a clumsy frontal assault. Time and again, Syrian tactical forces

just sat in their defensive positions and blasted away (inaccurately) until the

Israelis killed them or maneuvered them out of position. And while the

commandos did noticeably better with combined arms, an ability to improvise defensive

positions quickly, and a somewhat greater reactivity to Israeli moves, so too

did some of the Syrian forces in 1948, notably in their second assault on

Zemach and the fighting at Mishmar HaYarden. Moreover, the performance of the

Syrian Air Force in 1982 was absolutely dreadful, more than compensating for

any plaudits the commandos might have won. In terms of tactical leadership,

there was little, if any, improvement among Syrian forces despite Syria’s

significant economic development from 1948 to 1982.

A variety of other problems persisted or actually got worse

as Syria developed economically between 1948 and 1982. Syrian logistics were

not great in 1948, but neither did they have to be. Very little was asked of

them. Syrian logistics were awful in 1982, although corruption was a big part

of the problem. Syrian maintenance and operational readiness rates did not

improve much, nor did Syrian weapons handling. To some extent, all of these

issues need to be seen in relative terms: in 1982, the Syrians were operating

far more sophisticated equipment requiring far greater logistical needs than

they had in 1948. They were still bad, but they seemed to be keeping pace,

staying at the same mediocre level, even as the sophistication of their

equipment increased. That suggests an improvement that paralleled their rising

level of development.

The one area where that didn’t seem to apply was Syria’s air

force pilots. In 1982, they were utterly incapable of flying (let alone

fighting) their planes when they lost their GCI guidance. There is no parallel

in 1948, and this suggests that the MiG-23 and even the MiG-21 may have been

beyond the ability of even a better-developed Syria to employ properly.

In an absolute sense, the Syrian military of 1982 was vastly

more powerful than that of 1948. It was better armed, better trained, more professional,

larger, and had more combat experience. If they somehow could have fought each

other, the Syrian military of 1982 undoubtedly would have beaten the Syrian

military of 1948. Two things are noteworthy for our purposes, however. First,

many of the most crippling problems that the Syrians (and other Arab

militaries) have consistently experienced since 1948 in tactical leadership and

information handling remained unabated. If anything, they got worse. Second,

despite the significant improvement in Syria’s socioeconomic circumstances, its

problems with logistics, maintenance, weapons handling, and even combined arms

operations did not improve much, if at all. At best, they kept the same

mediocre pace with the increasing sophistication of Syria’s Soviet-supplied

kit.

All of this suggests that underdevelopment probably did have

an impact on the effectiveness of Arab militaries since World War II, but like

politicization, it came in certain areas, and not necessarily those that were

the most deleterious.