French battleship design had a style all of its own,

backed up by intensive work and study on ship behaviour, though this was often

of a theoretical rather than practical kind.

Change and Modernisation, 1890-1904

The next fifteen years were an era of unprecedented and

dramatic technological developments in all aspects of naval warfare, in guns and

ammunition, in torpedoes and mines, in electricity, searchlights and wireless,

in triple expansion engines and water-tube boilers and the appearance of the

first operational submarines. Ships completed in the 1880s were already

obsolescent when they first put to sea, totally obsolete a few years later as

the speed of change quickened.

For the Marine the fifteen years were also to involve a

major change in strategy, the full implications of which took time to be fully

accepted, no longer a guerre de course against Great Britain but urgent

attention against the new and more dangerous enemy nearer home. After Fashoda

it was clear that a colonial war with France could not be a success and

possibly lead to a loss of colonies. The colonial powers had secured their

areas of control or interest, the few remaining flashpoints were either

manageable or of less importance. Britain was making it clear that she intended

to retain control over the Suez Canal but would not stand in the way against

French ambitions in Morocco, a territory where Germany was showing disturbing

signs of interest. More serious was the evident wider ambitions of the German

Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had come to the throne in 1888 and in two years

had dismissed his Chancellor, Bismarck, and begun the building of an ocean

navy. Faced with this new challenge in the North Sea together with the threat

of a triple alliance, Italy, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire in the

Mediterranean, the need for an efficient modern balanced navy was now obvious

and recognised by most politicians. Despite some vocal political opposition and

a few areas where interests clashed, by the time of the formal 1904

Anglo-French Convention much had been achieved.

With the plaques for Alsace and Lorraine in the Paris Place

de le Concorde covered with black cloth, a permanent reminder of the defeat of

the French Army in 1870, the admirals had always to fight their corner against

the generals. Until 1901 battleship design reflected only modification and

improvement on the 1880s classes, otherwise similar in armament and performance

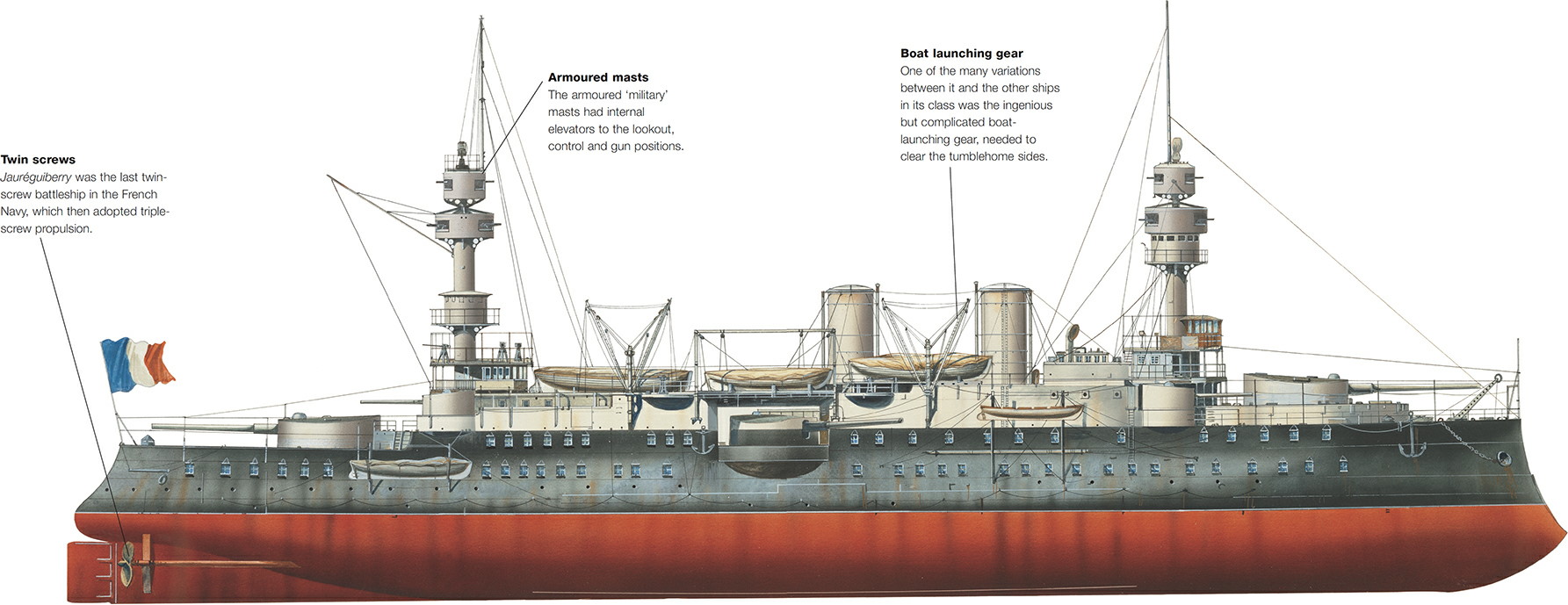

but differing in deck and mast layout. The first five, Carnot, Charles Martel,

Jauréguiberry, Masséna and Bouvet all displaced around 11,400 tons and were

armed with one single 12-inch gun turret fore and aft together with two 10-inch

guns in turrets on each sided amidships as main armament, all could reach 17.5

knots, and were in service by 1898. Completed in 1895-6 were also the last of

the ‘Second Rate’ coast defence ships, two 6,200 ton ships armed with a single

12-inch gun turret fore and aft. As the threat of an all-out Royal Navy

blockade attack on French ports receded no further ships of this type were

built.

With the next class of battleships, Charlemagne, St Louis

and Gaulois French builders produced ships that began to measure up to the

pre-Dreadnought battleships of the Royal Navy. They had the British style twin

12-inch gun turrets fore and aft, they displaced 11,000 tons, carried a

powerful secondary and torpedo armament and could steam at 18 knots. They were

followed by a reversion, the Henri IV of 8,000 tons whose main armament was

limited to single 10.8-inch guns in turrets fore and aft and her speed only 17

knots. To save weight this ship’s quarterdeck was only four feet above the

waterline, often invisible. Iéna that followed was slightly larger with 4

12-inch guns.

In place of the Coast Defence ships the concept of the

modern armoured cruiser, later after the First World War to evolve into the

heavy (8-inch gun) cruiser, began to appear with the construction of the Dupuy

de Lôme completed in 1895, a ship immediately conspicuous by an exaggerated ram

bow. Displacing 6,700 tons she was armed with two 7.6-inch and six 6.11-inch

guns and two 18-inch torpedo tubes, lightly armoured, no rigging for sail and a

maximum speed of nearly 20 knots Dupuy de Lôme marked an important stage in

modernisation. Five slightly smaller vessels followed, all with a main armament

of two 7.6-inch guns and were succeeded by the 11,000 ton Jeanne d’ Arc, the

first of what was to become a familiar sight in the First World War, the five

or six funnelled French warships. She carried a mixed gun armament, two

7.6-inch guns and fourteen 5.5-inch guns but could make the speed remarkable

for its time of 21.5 knots. Eleven more armoured cruisers in three classes,

three of the 9,200 ton Gueydon and 9,800 ton Gloire classes armed with two

7.6-inch and eight 6.4-inch guns, and five of the smaller Dupleix class with

eight 6.4-inch only. All had maximum speeds of 20.7 to 22 knots and were

completed between 1902 and 1904.

Despite the ending of colonial rivalries with Great Britain

and the new threats nearer home the protection of some overseas as well as home

bases was still regarded as a priority despite the costs and reduced threats.

Debate over the number and degree of developments and protection led to a

reduction in those overseas considered essential, by 1902 some twelve had been

reduced to five Martinique (Fort de France), Dakar, Diego-Suarez, Saigon and

Nouméa with one possible, Han Gay in Tonkin. For these there were to be two

cruiser ‘Flying Squadrons’, one based at Brest for the Atlantic and one at

Diego-Suarez for areas east of Suez, with single ships based on the others now

seen as of secondary value.8 More radical changes were to follow in the next

ten years.

For this strategy thirty-two cruisers, in the category of

Protected Cruisers entered service. These varied in tonnage, two very small of

2,400 tons, the majority between 3,300 and 5,000 and four of 7,000 tons or

over. Most had four 6.4-inch guns as main armament, all except three were

fitted with torpedo tubes, four were equipped for mine-laying, only the

D’Entrecasteaux with two 9.4-inch guns carried major fire power. All had speeds

of 19 to 22 knots with the exception of Châteaurenault, a very distinctive ship

in appearance being built to resemble a four funnelled passenger liner in

silhouette, and with a speed to reach 24 knots. Four small ‘torpedo cruisers’

of 1,280 tons were also built, to prove of little value.

The Jeune École obsession with torpedo boats continued with

an initial programme of two hundred and ninety-four boats of between 90-100

tons armed with a single spar or two of the much improved torpedoes in tubes. A

second programme ordered in 1904 and begun in the following year provided for a

further seventy-five boats to be fitted with a third tube. The poor sea-keeping

qualities of these small boats led, to the annoyance of on-going Jeune École

purists, to a parallel programme of torpilleurs de haute-mer, slightly larger

sea-going boats. These were given names rather than numbers. Except for the

first nine inadequate boats the remaining thirty-six varied in tonnage between

120 to 170, two, three, a few four torpedo tubes and two or three light 37mm

guns for self-defence. Except for the first nine speeds rose to twenty to

twenty-five knots. A number were still in service in the early 1920s, but the

very limited success of Japanese torpedo boats in their attack on Port Arthur

in 1904 was to show up their deficiencies.

The construction of this very large number or torpedo boats

created alarm across the Channel culminating in another nervous ‘naval scare’

in London in 1897. The Royal Navy saw a danger of swarms of small torpedo boats

dashing around making simultaneous co-ordinated attacks from different

directions on British battleships, confusing the big ships gunners defensive

fire. The British Admiralty ordered the design and construction of the first of

an entirely new class of warship, the Torpedo Boat Destroyer, at the time

referred to as T.B.D., but later shortened simply to ‘destroyer’. The first,

Havock, entered service in 1894, she displaced 240 tons, was armed with a 12

pdr gun and three 18-inch torpedo tubes and claimed a world record working

speed of 26.7 knots. Havock was regarded as a great success. Her size, speed,

mix of guns and torpedoes in a gamekeeper-poacher combination set the pattern

for successive generations of destroyers, British and world-wide.

The Marine was not slow to follow. Four proto-types were

launched in 1899-1900, followed by twenty-eight more between 1899 and 1904.

Tonnage averaged 300 tons and armaments for all were a 65 mm and six 47 mm

guns, two 15-inch torpedo tubes and speeds of 20 to 21 knots.

Even more far-reaching for the future than the destroyer was

serious experimental work on under-water craft, much favoured by the Marine

Minister, Pelletan. At the outset opinion was divided between arguments for

submersibles and arguments for submarines. Submersibles were generally steam

propelled surface warships with a record of being more easy to direct and

control while on the surface, but also more conspicuous and taking some ten

minutes before they could close down and dive for the brief periods during a

battle when they were required to submerge and attack the enemy vessels. The

submarine was designed to be a fully submerged warship, slow but a boat that

could approach a sea combat on the surface awash, and then dive very quickly

and by the technology of the time only be located if its periscope was visible.

Submerged underwater, though, the problems of clean-air breathing and hygiene

generally were proving difficult. The specialist underwater naval constructor

Gustav Zédé produced a small 30 ton electrically driven submarine, Gymnote in

the 1880s. In 1893 a larger boat, the Gustav Zédé appeared and proved a

success. She was followed by the 120 ton Narval, a steam-driven submersible

with speeds of 11 knots on the surface and 15 knots submerged. In 1899 the

steam-driven slightly larger submarine Farfardet later renamed Follet was

built, 185 tons on the surface and 200 submerged and carrying four 15-inch

torpedoes in the old ‘Dog Collar’ external launching gear. She was electric

powered and reached speeds of 12 knots and 8 knots surface and underwater.

Farfadet was followed by four Sirène class submersibles of 157 tons surface and

200 tons submerged to be propelled by steam petrol fuelled engines on the

surface and motors submerged. These followed an order for twenty submarines of

the very small Naiade class of only 68 tons to be propelled by petrol motors on

the surface and electricity while plunging, but these were soon seen to be

valueless and only one or two were actually build with instead in their place

three purely experimental larger boats with tonnages varying between 168 and

232 tons. The designer of the Narval, Laubeuf, returned to the cause of

submersibles with two Aigrette class boats of 172 tons surface and 371

submerged. The slightly larger Omega (later Argonaut) diesel propelled

followed. Another project, one with low costs in mind were the two very small

submarines of the Guêpe class designed to be carried on a transporter. Orders

for more were later cancelled but the political preference for boats, small and

cheap remained. Two more small experimental boats, Circe and Calypso, both

generally similar to the Aigrettes followed, petrol driven and armed with six

improved torpedoes. However, all these boats had seriously limited range of

action and none could stay submerged for very long. Seen as an answer to these

handicaps an old cruiser, Foudre, was fitted with deck cranes to be used as a

transport for smaller submarines but the practical difficulties and delays in

dropping the boats in the midst of a battle were obvious. Eyes turned to Royal

Navy construction. The idea that submersibles and submarines could be another

inexpensive form of defence (there were even plans for a total submarine force

of one hundred and thirty boats by 1919) became discredited. Submarine theory

began to move towards the British pattern of larger and faster boats designed

for offensive operations.

Organisation of the Marine

After a number of unsatisfactory earlier arrangements a

proper professional organisation for the Marine headed by a general staff was

set up in 1882. It included directorates (bureaux) for movement and operations,

statistical surveys for the Marine and foreign navies, for reserves, for

mobilisation and for coast defence with a little later one for personnel. In

1899-1902 much of the authority of the Chief of Staff was transferred to the

Minister’s office leaving the Chief of Staff concerned with little more than

day to day administration. Personality, doctrine and strategic friction and

opinion clashes led to frequent changes at Chief of Staff and fleet command levels.

A Conseil Supérieur de la Marine composed mainly of serving officers advised

the Minister on national policy as a figurehead body, the Minister did not have

to follow its recommendations. Until 1902 naval officer inspector-generals

watched over the day-to-day efficiency of ships and bases, this was replaced by

an administrative control corps who reported direct to the Minister and was

principally concerned with budgetary matters.

The manpower strength of the Marine rose from some

42,000(including pilots, bandsmen and boys) in 1880 to some 52,000 by 1904, the

total not including reservists. Recruitment of seamen was based on men from the

coastal areas where their youth had been spent at sea in fishing or as crew

members of a larger ship. Some ten per cent of these men were illiterate. They

could in theory be required to serve for as long as five years, thereafter they

were placed on a reserve up to the age of fifty and liable for recall. In

return these men, known as inscrits the whole system being called inscription

militaire, received certain privileges including special fishing rights,

reduced rail fares, the opportunity of contributing to a not very generous

pension scheme and exemptions of their homes from any military billeting. The

system led to acute drafting problems, ships going to sea with men hurriedly

moved from one vessel to another, or with inadequate crews.

Far more serious though was the indiscipline, frequently

open, and a legacy from the Post-Revolution rift in French society. The petty

officers (sous-officiers) were not obeyed, officers obeyed only in an

insubordinate or perfunctory way. One naval officer commented that he often

heard the Internationale sung in the seamen’s mess decks and saw real hatred in

the eyes of the individual sailors. On some occasions men simply stayed on the

quayside refusing to embark. The petty officers were in despair, the officers

dismayed and discouraged. The traditional paternalistic officer-sailor bonding

with officers ‘tutoying’ to sailors had gone. Little attention seems to have

been given to individual sailors welfare nor much sport organised. Ashore, many

sailors activities centred on more traditional relaxations in areas of bases

and ports known collectively as the Rue d’Alger. Ships went to sea not only

inadequately crewed but with inefficient stores and incomplete ammunition

holdings to add to the poor morale.

A number of sous-officiers were later commissioned as

officers, but the majority of deck officers were products of secondary schools,

some of which had a ‘navy stream’ for those wanting to join the Marine. Again

in the majority most were middle class with some ten per cent from the

aristocracy. Breton names frequently appear. Candidates had to have passed a

preparation naval baccalauréat examination at almost invariably a fee-paying

school. Those accepted were then sent to the officers training establishment at

Brest which took the form of an old wooden hulk, the Borda, still armed with

muzzle-loading guns. Cadets slept in hammocks and were treated and trained as

ordinary sailors, there does not seem to have been any academic professional

teaching. After a year as aspirants the bordaches as they proudly called

themselves were sent to sea in a training ship, usually an old cruiser where their

treatment differed little from that of the Borda. After a further period back

on Borda still as aspirants a return to sea as enseignes 2e classe for two

years followed, ships proceeding on long voyagers visiting foreign ports.

Finally as enseignes de vaisseau and still very much under supervision the

young officer received his first appointment as a ship’s officer. Engineer

officers were mostly recruited from merchant shipping—and were paid very much

better. A small number had had a measure of professional training at a civilian

college.

For career development young officers were then sent on

specialist training, torpedo, gunnery or signals. Mid-career wider training in

naval strategy and tactics was opened in 1895 at an École Supérieure de la

Marine which supervised instruction initially at sea on three cruisers. It was,

however, very quickly replaced, following a change of government by an École

des Hautes Études de la Marine in Paris in a course lasting eight months, only

to be wound up with a return to the 1895 arrangement following another change

of government. Old school officers held such training with disdain and it did

not seem to have served any real value.

Only a minority of career officers practised religion and

the abolition of naval chaplains in 1907 was not opposed. For many naval

service was a career move, especially if it led to marriage with a daughter of

a senior admiral or general, or the wealthy. A series of improvements in naval

medicine began in 1875, ships doctors were required to have a professional

qualification. The standard of the professional qualification was raised in

1895 and proper fully professional naval schools opened at Bordeaux in 1890 and

in Toulon in 1896.

The metropolitan naval bases in 1904 remained Calais, Cherbourg, Brest, Lorient, Rochefort and Toulon with Dunkerque for torpedo boats. Dry docking facilities were only slowly developed despite the increasing size of ships. Both management and industrial relations were poor. The use of private dock facilities at Le Havre, St Nazaire and Marseille was of only limited value. The major shipbuilding slipways and fitting out yards were at Brest and Lorient for larger ships, with Cherbourg, Rochefort, on the Gironde near Bordeaux and at La Seyne near Toulon for smaller vessels. Other smaller yards included one at Le Havre and one for torpedo boats as far inland as Nantes. In the rapidly developing international naval construction race France with its limited shipbuilding capabilities, together with obsolete organisation and recruitment arrangements was fast falling behind.

In the colonial empire even the five bases given priority in

1902 were now appearing more as aspirations than realities as the size of

warships increased. Facilities adequate for small warships were inadequate for

the larger vessels entering service which might need dry-docking, particularly

if damaged in battle. Thinking became increasingly concentrated on North

Africa, especially Bizerte, with significant developments to follow in the last

ten years before the First World War.