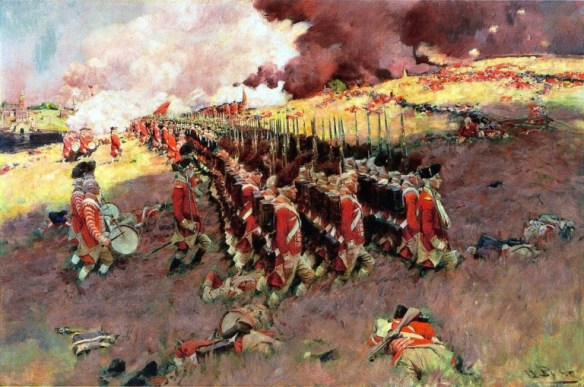

British troops advance to within musket range at Bunker Hill, as depicted by 19th Century American artist Howard Pyle.

The reasons why, in combating the American rebels, the

British put so much emphasis on what were (by European standards) seemingly

outdated shock tactics are explored in detail in the next chapter. Here it is

necessary to examine how the redcoats delivered their fire in combat and

whether or not it was generally effective.

Strikingly, there is little evidence that British infantry

in action in America often employed the regulation firings, whereby volleys

were delivered in strict succession by the battalion’s fire divisions (whether

by the four grand divisions, the eight subdivisions, or the sixteen platoons)

in prearranged sequences. This is hardly surprising for three reasons. First

(as discussed in the next chapter), throughout the war the British preferred to

spurn the firefight wherever possible in favor of putting the rebels quickly to

flight at the point of the bayonet. Second (as noted in the last chapter), a

combination of broken ground and the battalion’s extended frontage often

prevented field officers from exerting close control over the whole in action,

compelling captains to exercise an unconventional degree of tactical autonomy

in handling their companies. It was only natural that this tactical

decentralization extended to musketry. Third, because, for most of the war, the

rebels lacked good cavalry and most of their infantry were unlikely to adopt

the tactical offensive, the British did not need to ensure that a fraction of

the battalion was always loaded to repel any sudden, determined enemy advance.

These three factors ensured that British battalions on the attack seem commonly

to have thrown in a single “general volley” (or “battalion volley”) immediately

prior to the bayonet charge.

When sustained exchanges of musketry did occur, as at

Cowpens or Green Springs, it seems likely that each company loaded and fired

independently of the others under the command of its captain or senior

subaltern. Evidence of this can be found in George Harris’s later account of

the action at the Vigie on St. Lucia, where (as major in the 5th Regiment) he

commanded the single grenadier battalion: “on my ordering the 35th [Regiment’s

grenadier] company, commanded by Captain [Hugh] Massey (from a reserve of three

companies which I kept under cover of a small eminence) to relieve the 49th

[Regiment’s grenadier] company, he was in an instant at his post, and as

quickly ordered the company to make ready, and had given them the word

‘Present!’ when I called out, ‘Captain Massey, my orders were not to fire;

recover!’ This was done without a shot, and themselves under a heavy fire.” In

another possible example, at the battle of Camden, a British officer was

“ungenerous enough to direct the fire of his platoon” at the horse of Colonel

Otho Williams. The rebel adjutant escaped injury from the British volley only

because, as Williams recounted, “I was lucky enough to see and hear him at the

instant he gave the word and pointed with his sword.”53 More conclusively, in August

1780 Lieutenant Colonel Henry Hope directed the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers

that, when the “Preparative” was beaten in action, the corps was “to begin

firing by companies, which is to go on as fast as each is loaded till the first

part of the General, when not a shot more is ever to be fired.”

Although British musketry was supposed to have been quite

effective by European standards, contemporary eyewitnesses and modern

historians have tended to give the impression that the redcoats were generally

no match for the American rebels in the firefight. It is of course impossible

to qualify this phenomenon with any degree of precision since, for any given

exchange of fire, we cannot precisely document the number of troops engaged on

either side, the total rounds discharged, or even the casualties they

inflicted. Yet one particularly striking example may serve to indicate how the

premise may have had some basis in reality. At Guilford Courthouse Cornwallis’s

initial attack pitted about 1,100 British and German regulars against roughly

1,600 smoothbore-and rifle-armed militia and light troops, mostly posted behind

a rail fence that separated the ploughed farmland to their front from the woods

to their rear. Once the British line had advanced to within about 150 yards of

the enemy, the rebels opened a general fire that appears to have inflicted

numerous casualties. For example, Lieutenant Thomas Saumarez (with the 23rd

Regiment, on the left wing) noted that the rebel shooting was “most galling and

destructive,” while Dugald Stuart (an officer with the 2nd Battalion of the

71st Regiment, on the right) later rued: “In the advance we received a very

heavy fire, from the [North Carolina Scotch-] Irish line of the American army,

composed of their marksmen lying on the ground behind a rail fence. One half of

the Highlanders dropped on that spot, [and] there ought to be a pretty large

tumulus where our men were buried.”

One participant on the rebel left later recalled that “after

they [i.e., the rebels] delivered their first fire (which was a deliberate one)

with their rifles, the part of the British line at which they aimed looked like

the scattering stalks in a wheat field when the harvest man has passed over it

with his cradle.” By contrast, the volley that the British battalions delivered

at much closer range, immediately prior to their charge, was almost wholly

ineffective (rebel returns having indicated that the North Carolina militia

sustained only eleven killed and wounded in the course of the whole action). Indeed,

Henry Lee later reported of the North Carolina militia (which comprised almost

two-thirds of the first rebel line and fled when the British rushed forward)

that “not a man of the corps had been killed, or even wounded.”

The apparent disparity in the effectiveness of the British

and rebel fire in this incident does not appear to have been wholly

unrepresentative. To explain this, one is tempted to point to the popularly

accepted view that, unlike in Europe, most males in America had access to firearms,

which they were very proficient in handling. Although some British participants

in the war subscribed to this view,58 it is likely to have been the case only

in the wilder backwoods and on the frontier. Moreover, because the Continental

Army and the state regular regiments filled their ranks largely with landless

laborers (many of them recent immigrants), it follows that a good proportion of

rebel enlisted men were hardly dissimilar to their British and German

counterparts.

If most rebel regulars and militia were not inherently

skilled in handling firearms, then it is necessary to consider the common

assumption that, unlike European regulars (who supposedly simply pointed their

muskets in the general direction of the enemy and blazed away on command), the

Americans tended to deliver independent, well-aimed fire in combat. This may

well have been true of the lively skirmishing that characterized the petite

guerre, in which individuals typically moved, sought cover, and fired largely

at their own initiative. Moreover, rebel militia used rifles more often than is

sometimes realized, particularly in the South (as in the case of the North

Carolina militia at Guilford Courthouse). For decades historians have been

playing down the combat effectiveness of riflemen in America by pointing to

their inability either to match the rate of fire of smoothbore-armed troops or

to perform bayonet charges. While both of these points are valid, riflemen were

undeniably able to do horrifying execution when employed as auxiliaries to

smoothbore-armed troops. If thrown forward as a screen, riflemen were able to

get off one or two destructive fires at the advancing enemy before retiring to

the cover of their musket-armed compatriots in the main line — as occurred at

Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. In addition, riflemen were able to support

their fellow infantry during a static firefight by picking off enemy officers,

as occurred at Freeman’s Farm.

But if smoothbore-armed troops were likely to deliver

independent, aimed fire when engaged in the kind of skirmishing that

characterized the petite guerre, this was not the case in stand-up engagements

in the open field, for which rebel regulars and militia alike were trained to

employ more or less conventional volleying systems. Indeed, for much of the

war, the rebels used the 1764 Regulations or its British or colonial variants

as their standard drill.63 Because the experience of three years of war showed

that the British-style firings were difficult for the relatively inexperienced

rebel forces to master, the drill manual that Major General Steuben compiled

for them in 1778 prescribed a simpler variant, whereby the different battalions

within the line of battle could deliver general volleys in sequence.

The counterpart to the questionable notion that rebel troops

generally delivered independent and thus accurate fire in action in America is

the widespread assumption that European volleying techniques were ineffective

because they were calculated primarily to terrify rather than to kill and maim.

Admittedly, by the time of the American War, this kind of “quick-fire” mania

appears to have been the hallmark of the Prussian infantry, who reputably were

able to loose an astonishing six rounds per minute and whose king wrote in 1768

that “a force of infantry that loads speedily will always get the better of a

force which loads more slowly.” Interestingly, the subject of speed also

figured in contemporary British directives on musketry training. For example,

the 1764 Regulations laid down that, during the performance of the “platoon

exercise,” the “motions of handling cartridge, to shutting the pans,” and “the

loading motions” (that is, the fourth to sixth and the eighth to twelfth of the

fifteen motions) were “to be done as quick as possible.” Similarly, in 1774

Gage reminded the British regiments in Boston that in plying the firelock the

soldier “cannot be too quick” in performing the motions, “more particularly so

in the priming and loading,” and that “there should be no superfluous motions

in the platoon exercise, but [it is instead] to be performed with the greatest

quickness possible.” Strikingly, after the costly Concord expedition, one flank

company officer complained that the inexperienced redcoats had “been taught

that everything was to be effected by a quick firing” but that the determined

harassment they experienced during the return march to Boston had disabused

them of the notion that the rebels “would be sufficiently intimidated by a

brisk fire.”

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to argue that the Prussian

quick-fire mania had permeated the British Army by the time of the American

War. Significantly, when in 1781 military writer John Williamson decried the

“very quick” time adopted for “the performance of the manual,” he reasoned that

“it does not appear that a battalion can fire oftener in the same space of time

since the quick method has taken place, than before it.” Another military

writer, Lieutenant Colonel William Dalrymple, made the same point in 1782.

While he asserted that all motions with the firelock were “to be executed with

the utmost celerity,” he nevertheless argued that British soldiers should be

able to fire three times a minute (in other words, half the best Prussian

quick-fire rate) and scarcely ever miss at ranges between fifty and two hundred

yards. As Dalrymple’s comment suggests, if the British emphasis on rapid

priming and loading did not markedly increase the battalion’s rate of fire, it

certainly was not intended to diminish the accuracy of that fire. Indeed, the

leading authority on the performance of British long arms in this period has

argued that the eighteenth-century British fire tactics remained consistently

and firmly wedded to making the infantryman’s musketry as deadly as possible. The

dominant perspective probably remained that expressed by Wolfe when in December

1755 he reminded the 20th Regiment that “[t]here is no necessity for firing

very fast; a cool and well-leveled fire, with the pieces carefully loaded, is

much more destructive and formidable than the quickest fire in confusion.” It

is instructive to note that Wolfe himself played a significant role in the

introduction of the Prussian “alternate fire” volleying system into the British

Army.

If the Prussian quick-fire method did not quite permeate

into British training in the years before the American War, one might argue

instead that volleying was in itself inherently prejudicial to accurate fire.

There remains some disagreement on this question. Historians have commonly asserted

that, to have had any chance of hitting his target, a man had to choose his

moment to pull the trigger. Dr. Robert Jackson, who served in the American War

as assistant surgeon to the 71st Regiment, subscribed to this view: “The

firelock is an instrument of missile force. It is obvious that the . . . missile ought to be directed by aim,

otherwise it will strike only by accident. It is evident that a person cannot

take aim with any correctness unless he be free, independent, and clear of all

encumbrances; and for this reason, there can be little dependence on the effect

of fire that is given by platoons or volleys, and by word of command. Such

explosions may intimidate by their noise; it is mere chance if they destroy by

their impression.”

Although Jackson’s argument sounds persuasive, not all

contemporaries shared his opinion that volleying was incompatible with

accurate, aimed fire. In fact the 1764 Regulations explicitly directed that,

when given the order to present, the soldier should “raise up the butt so high

upon the right shoulder, that you may not be obliged to stoop so much with the

head (the right cheek [is] to be close to the butt, and the left eye shut), and

look along the barrel with the right eye from the breech pin to the muzzle.”

Military writers likewise commonly advocated that the men should aim carefully

before firing. For example, Major General the Earl of Cavan recommended that

officers “have at the breech [of the firelock] a small sight-channel made, for

the advantage and convenience of occasionally taking better aim.” Similarly, in

the directions for the training of newly arrived drafts and recruits issued

three days before the battle of Bunker Hill, Lieutenant General Gage directed

that “[p]roper marksmen [are] to instruct them in taking aim, and the position

in which they ought to stand in firing, and to do this man by man before they

are suffered to fire together.”

Furthermore, if volleying was incompatible with accurate,

aimed fire, then it is difficult to understand why the army invested such

effort in practicing the men in shooting. As John Houlding has shown, although

before 1786 regiments did not receive sufficient quantities of lead in

peacetime to fire at marks, in wartime troops spent a good deal of time shooting

ball when they were not in the field. In America, shooting at marks was a

common element of the feverish training that preceded the opening of each

campaign season; indeed, it occurred almost on a daily basis during the tense

months before the outbreak of hostilities in 1775. Here two examples of the

ingenuity and effort invested in this activity will suffice. At Boston in

January 1775, Lieutenant Frederick Mackenzie of the 23rd Regiment wrote:

The regiments are frequently practiced at firing with ball

at marks. Six rounds per man at each time is usually allotted for this

practice. As our regiment is quartered on a wharf which projects into part of

the harbor, and there is a very considerable range without any obstruction, we

have fixed figures of men as large as life, made of thin boards, on small

stages, which are anchored at a proper distance from the end of the wharf, at

which the men fire. Objects afloat, which move up and down with the tide, are

frequently pointed out for them to fire at, and premiums are sometimes given

for the best shots, by which means some of our men have become excellent

marksmen.