Royal Navy air capability in 1941

The Royal Navy required a strategy for dealing with Japan

that took realistic account of its available resources in 1941. However, it

also needed to apply the right capabilities and fighting tactics. Here,

understanding the new potential of air power at sea and applying the lessons of

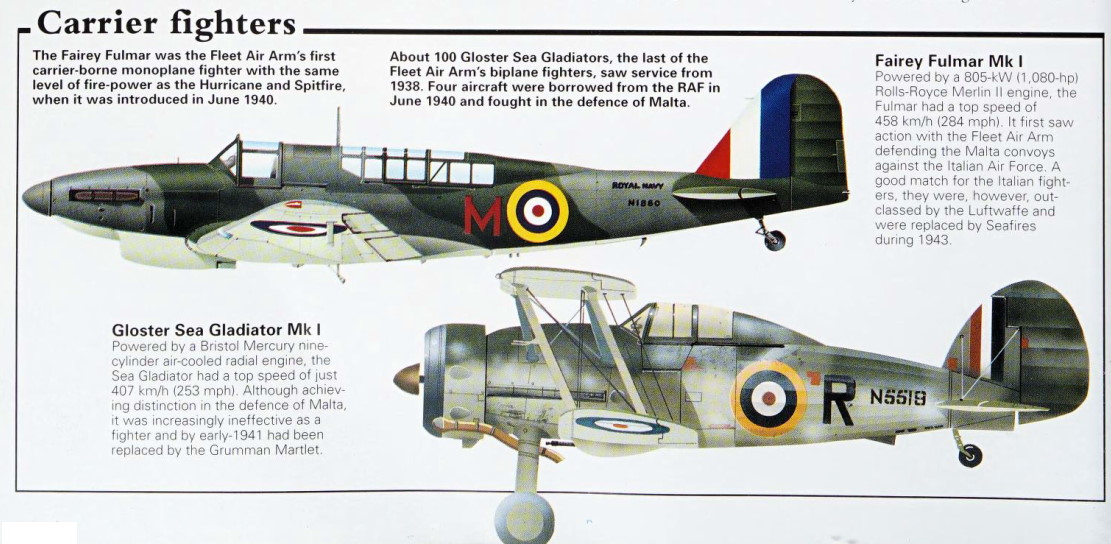

the war to date was particularly important. The Fleet Air Arm entered the

European war with obsolescent aircraft, and also faced low priority for

development and production. Once the war got underway, a combination of

prioritisation by the Ministry of Aircraft Production on key Royal Air Force

types, procurement mismanagement and shifting operational requirements caused

development of the new generation fighter and strike aircraft ordered in 1939

and 1940 to move painfully slowly.

Of the three aircraft taken forward, none ultimately reached

service until 1943. Only one then proved operationally adequate, albeit not in

its intended role. They were the Fairey Barracuda torpedo bomber, the advanced next

generation torpedo strike reconnaissance (TSR) aircraft to replace the Albacore

and Swordfish; the Fairey Firefly specification N 8/39 two-seater escort fighter

to replace the Fulmar; and the Blackburn Firebrand high-performance single seat

fighter. The failure of the Barracuda was partly owing to the cancellation of

the advanced Exe engine by the Ministry of Aircraft Production in 1940 to

concentrate on other engine priorities. This was a decision beyond the Royal

Navy’s control, but it led to substantial and unsatisfactory redesign. The

development of the Firefly was inhibited by changing perceptions of fighter

requirements and the best means of meeting these. It eventually proved a useful

aircraft, but as a fighter-bomber and night-fighter rather than mainstream

dayfighter, where it could not compete with contemporary US Navy fighters. It

was not fully operational until 1944. The Firebrand was a high-performance

single-seat fighter able to take on land-based aircraft, but was fatally

compromised by hasty design and too many conflicting requirements.

The Norwegian campaign persuaded the Fleet Air Arm that its

most critical need was a dedicated naval fighter with sufficient performance to

counter the latest land-based strike aircraft and their escorting fighters.

Experiments here with radar-assisted fighter direction emphasised the

desirability of an agile aircraft able to gain height and distance quickly for interception.

The first Royal Navy radar-controlled interception at sea occurred on 23 April

1940, using the converted anti-aircraft cruiser Curlew as a radar picket. The

Norway experience also demonstrated the potential for integrating new

technology: radar, lightweight VHF communications (which were far ahead of the

US Navy) and radio homing. Essentially, the Fleet Air Arm was now reaching for

a ‘Battle of Britain’ fighter defence concept, based on new perceptions of the

threat and available technology. Two factors, therefore, came together here to

drive a fundamental shift in fighter philosophy: the threat from high-speed

aircraft and the technical means to counter this threat with carrier-based

fighters, using the emerging Royal Air Force fighter direction techniques.

The result was the specification of the new Firebrand

single-seat fighter in July 1940, and the decision to meet the gap before the

Firebrand’s arrival by ordering the Grumman F4F Wildcat from the United States,

which the Royal Navy named the Martlet. This followed an extensive debate over

how to reconcile the traditional requirement for a long-range escort fighter to

support carrier strike forces, which in the Fleet Air Arm view required a

dedicated navigator as well as pilot, and the new need to defend the fleet

against high performance attackers, where equivalent fighter performance was

needed, implying single seat and acceptance of shorter range. The Admiralty

continued to worry about the difficulties a single-seat fighter might face with

navigation until well into 1941. The initial conclusion was that two aircraft

were needed. By September 1941 it was already clear the Firebrand was well

behind schedule and could not be operational before mid-1943.

Meanwhile, deploying the interim Martlet from Royal Navy

carriers posed a problem. Without folding wings, none of the lifts in Ark Royal

or the first three Illustrious class were large enough to accommodate them. The

solution was to ask Grumman to produce a folding wing variant and eventually to

adopt the US Navy practice of deck parking. Because of these limitations, the

first Wildcats delivered were used in a land-based role for the defence of

Scapa Flow. Designing and producing a folding wing took much longer than hoped,

and the Admiralty briefly considered undertaking the work in the United

Kingdom. In early 1941 it expected the folding wing variant to begin arriving

in the middle of the year, but this proved wildly optimistic. Nevertheless, at

the end of 1941, the Royal Navy still assessed the Wildcat the best naval

fighter in the world. Trials had by now shown that it was more manoeuvrable

than a Hurricane I, was faster at all heights up to 15,000ft, and climbed

better too. The Royal Navy ordered 100 aircraft in July 1940, 150 more in

December 1940 and 200 in October 1941. It appears a further eighty-one were

taken over from French orders in mid-1940. Grumman had originally promised

delivery of twenty aircraft per month from late 1940, sufficient to equip the

Fleet Air Arm frontline fighter force by the following autumn. This would have

given Royal Navy carriers broadly the same fighter capability as the US Navy in

confronting the IJN in late 1941 and in 1942. The US Navy had initially

selected the Brewster Buffalo as its preferred naval fighter, but switched to

the Wildcat in mid-1941, partly on the basis of British experience. The Wildcat

then remained its primary naval fighter throughout 1942. The Buffalo, as we

have seen, became the mainstay of British fighter defence in Malaya.

However, by the end of 1941 Grumman had delivered less than

half the numbers contracted and paid for and, crucially, none had the folding

wings, essential to the Royal Navy, which Grumman had also promised. Churchill,

who monitored the Fleet Air Arm fighter problem throughout 1941, described this

as ‘a melancholy story’. In September that year, in typical fashion, he cut to

the heart of the issue. ‘All this year it has been apparent that the power to

launch the highest class fighters from aircraft carriers may re-open to the

Fleet great strategic doors which have been closed against them.’ He instructed

that – ‘the aircraft carrier should have priority in the quality and character

of suitable (aircraft) types’. The latter was, of course, easy to say, but much

harder to deliver. The US Navy, by then also acquiring Wildcats, blamed the

delays on acute shortages of materials across the US aircraft industry, owing

to concentration on the four-engine bomber programme.

The end of 1941, therefore, found the Fleet Air Arm badly let

down by American industry and desperately trying to plug its fighter gap

through stopgap adaptations of the Hurricane and Spitfire, neither of which

were really suitable for carrier operation. Once it became clear that Wildcat

deliveries would be delayed, 270 Hurricanes were released to the Fleet Air Arm

between February and May 1941. Inevitably, some of these Royal Air Force

releases were of poor quality. Alexander again summarised the status of Fleet

Air Arm procurement for the prime minister in early December. He explained why

the Hurricane and Spitfire, although necessary as stopgaps, were inherently

unsuitable for carrier operation. It remained essential to maximise Wildcat

supplies until new British naval fighters were available, but supplies could only

be assured by asking the United States to prioritise naval fighter over heavy

bomber production. Despite Alexander’s insistence that the Spitfire was

unsuitable, it appears that the possibility of converting Spitfires for carrier

use, including the provision of folding wings, was considered as early as

February 1940, but was ruled out at this time because of the impact on Fighter

Command requirements. The idea was then resurrected in September 1941,

technical issues were resolved by January 1942, and an initial order placed for

250 aircraft, by now designated the Seafire. The modification of the Spitfire

for naval use inevitably still took time, and the first twenty-eight aircraft

were not delivered until July 1942. At that point, deliveries were expected to

run at twenty-five per month and by late August the initial order for 250 was

expanded to 452 for the end of 1943. This reflected the view by then that the

Firebrand would have to be abandoned.

Given the delay to the Barracuda, the Fleet Air Arm also

considered the merits of purchasing strike aircraft from the United States. The

current US Navy torpedo bomber, the Douglas Devastator, offered no significant

performance advantage over the Swordfish or its Albacore successor, which began

coming into service in 1940. The US Navy did have an excellent dive-bomber in

the Douglas Dauntless SBD2, but the Royal Navy had long chosen to prioritise

torpedo attack over dive-bombing, and its carriers had insufficient capacity to

carry reasonable numbers of both types. There is a compelling argument here

that the US Navy ended up prioritising the dive-bomber because its aerial

torpedoes did not work satisfactorily. By contrast, the Royal Navy had

excellent torpedoes. The Fleet Air Arm was, however, impressed with the forthcoming

Grumman TBF Avenger, which would prove the outstanding naval strike aircraft of

the war. Two hundred were ordered in late 1941 under lend-lease, but did not

reach the Royal Navy until 1943.

This background meant that until well into 1942, the Fleet

Air Arm was largely dependent on obsolete biplane strike aircraft dating from

the mid-1930s and a more modern fighter of interim design, the Fulmar,

introduced in 1940. Indomitable, completed in autumn 1941 with larger lifts and

extra hangar space, was equipped with Hurricanes from the start, while

modifications to Illustrious and Formidable in the United States in late 1941

enabled them to deploy Wildcats when they rejoined the fleet at the end of the

year. While they were not competitive with the latest IJN and US Navy carrier

aircraft, the limitations of the standard British Fleet Air Arm types can be

overstated. The Fulmar, as primary fighter from 1940, could not match a Zero

for speed or manoeuvrability, but it was still quite fast enough to catch the

most modern loaded strike aircraft, and had other advantages both as an

interceptor and reconnaissance aircraft. It was more robust than a Zero, could

dive at 400mph (faster than almost all contemporaries and a speed which would

cause a Zero to break up), had a four-hour endurance, and was an excellent gun

platform with large ammunition capacity (which was a Zero weakness), all of

which, when allied to radar control, made it a useful defensive fighter.

The Swordfish and Albacore torpedo bombers had reasonable

range, a good communications fit, were married to an excellent torpedo, and

their biplane manoeuvrability was an advantage in marginal flying weather. The

Fleet Air Arm torpedo here was the 18in Mark XII introduced in 1940. Contrary

to the impression often given that the Royal Navy was backward in aerial

torpedo capability, the Mark XII could be dropped at up to 200ft (61m) and 150

knots, making it easily comparable to the IJN Type 91. It also had two speed

options, an excellent warhead and the option of an advanced detonating pistol,

the duplex magnetic proximity fuse. In addition, it had gyro-angling so the

attacking aircraft could offset, rather than flying direct at the target.

The Fleet Air Arm’s Swordfish and Albacore torpedo bombers

could not match their IJN counterparts for speed and range, but compensated

through their ability to operate at night or in bad weather, and they had high

reliability. It is doubtful either IJN or US Navy aircraft could have taken off

in the conditions prevailing in Ark Royal on 26 May for the crucial attack on

the Bismarck. In addition, from early 1941 significant numbers were fitted with

ASV air surface search radar, giving them a night and bad weather search and

attack capability which neither the IJN nor US Navy could match. The first

airborne radar sets, known as ASV 1, were deployed in Fleet Air Arm aircraft in

late 1939, but were fragile and unreliable. The much improved ASV 2, with an

effective range of about 15 miles to detect a medium-sized warship, began to be

deployed in early 1941. The 825 Squadron embarked in the new carrier Victorious

were entirely ASV 2-equipped, and this facilitated their night attack on

Bismarck on 24 May. Some aircraft in Ark Royal were also equipped, enabling

them to operate against Bismarck in the atrocious weather prevailing two days

later. Judged, therefore, as an overall weapon system, the Fleet Air Arm

torpedo bombers were effective and competitive.

By the autumn of 1941, despite the limitations of its

aircraft both in numbers and quality, the Royal Navy carrier fleet had achieved

notable operational successes across different theatres and under different

commanders, amply demonstrating that the Royal Navy was definitely not tied to

a conservative battleship mentality. One measure here is that the Royal Navy

had sunk or disabled five modern or modernised capital ships through aerial

torpedo attack by end May 1941. At Taranto in November 1940, just eleven Fleet

Air Arm Swordfish sank or disabled three modern or modernised Italian battleships,

while eighty-nine IJN B5N2s were required to sink or disable five older US Navy

battleships in the first-wave attack at Pearl Harbor. While the IJN is

invariably credited with sinking the first capital units at sea (Prince of

Wales and Repulse), the Fleet Air Arm had previously disabled a modern German

battleship at sea (Bismarck) and come close to disabling another, the modern

Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto, at Matapan. They had also severely disabled

the new French battleship Richelieu at Dakar on 8 July 1940.

The Royal Navy had also completed more modern carriers than

either the IJN or US Navy, even if, for all the reasons discussed, it badly

lagged both in the number and quality of frontline aircraft, together with

trained and experienced crews. By autumn 1941 the Royal Navy had completed five

large modern fleet carriers, against four by the IJN, and three by the US Navy.

The IJN and the US Navy had also each completed a single light carrier earlier

in the 1930s. Despite all its procurement problems and heavy wartime attrition,

frontline air strength had almost doubled in size after two years of war, and

it would continue grow steadily into 1942. Relevant figures here are as

follows:

Aircraft reserves by autumn 1941 were also substantial

compared to those of the IJNAF. At the end of September 1941, alongside the

frontline strength recorded above, there were 141 strike aircraft and

seventy-two fighters allocated to training, a further 540 and 335 respectively

in general reserve and fifty-seven and fifty-five in transit.

The Royal Navy nevertheless had to divide its carrier fleet

across four theatres, Atlantic, the two ends of the Mediterranean, and the

Indian Ocean, and the initiation of the Russian convoys from late 1941

effectively added a fifth theatre, the Arctic. This made it impossible further

to explore and train for the multi-carrier operations and mass strike tactics

which the Royal Navy had investigated in the 1930s, and which the IJN developed

so assiduously during 1941. In theory, this left it poorly placed to handle a

mass carrier engagement of the Coral Sea or Midway type, which the IJN and US

Navy would experience in mid-1942. However, by mid-1941 the Royal Navy had made

innovations which partly compensated for lack of numbers and quality of aircraft.

Both the US Navy and IJN had embraced an operational philosophy based on the

single massive strike, which made it difficult to manage the more flexible

flying cycle required to handle the competing tasks and demands of a

multi-threat environment. The Royal Navy, by contrast, emphasised operational

flexibility with rapid switches of aircraft tasking. The evolution of this

sophisticated multi-role flying cycle is well illustrated in some of the

reports on Force H operations by Vice Admiral Somerville as early as autumn

1940. These show the execution of techniques and tactics, including radar

pickets, which would still be in use in the 1960s, and were quite beyond US

Navy and IJN capability at that time.