The Toba-Fushimi fighting marked the opening battle of the

Boshin (dragon) Civil War, named after the Chinese zodiacal cyclic character

that designated the year 1868. The new army fought under makeshift arrangements

with unclear channels of command and control and no reliable recruiting base.

Samurai and kiheitai units paradoxically were fighting in the name of the

throne, but they did not belong to the throne. To correct this anomaly and

defend the court, which was in open rebellion against the shogunate, in early

March 1868 the newly proclaimed imperial government created various

administrative offices, including a military branch. The next month it

organized an imperial bodyguard, about 400 or 500 warriors, composed of Satsuma

and Chōshū units augmented by veterans of the Toba-Fushimi battles, yeomen, and

masterless warriors from various domains, who reported directly to the court.

The imperial court next notified domains to restrict the size of their local

armies and contribute to the expenses of a national officers’ training school

in Kyoto.

Within a few months, however, authorities disbanded the

ineffective military branch and the imperial bodyguard, which lacked modern

equipment and weapons. To replace them, in April authorities established the

military affairs directorate, composed of two bureaus: one for the army, one

for the navy. The directorate drafted an army organization act based on

manpower contributions from each domain proportional to its respective annual

rice production. This conscript army (chōheigun) integrated samurai and

commoners from the various domains into its ranks.

As the Boshin Civil War continued, the newly formed military

affairs directorate had expected to raise troops from the wealthier domains. In

June 1868 it fixed the organization of the army by making each fief

responsible, at least in theory, for sending to Kyoto ten men per each 10,000

koku of rice the domain produced. The policy put the government in competition

with the domains to recruit troops, a contradiction not remedied until April

1869 when it banned domains from enlisting soldiers. The quota system to

recruit government troops, however, never worked as intended, and the

authorities abolished it the following year.

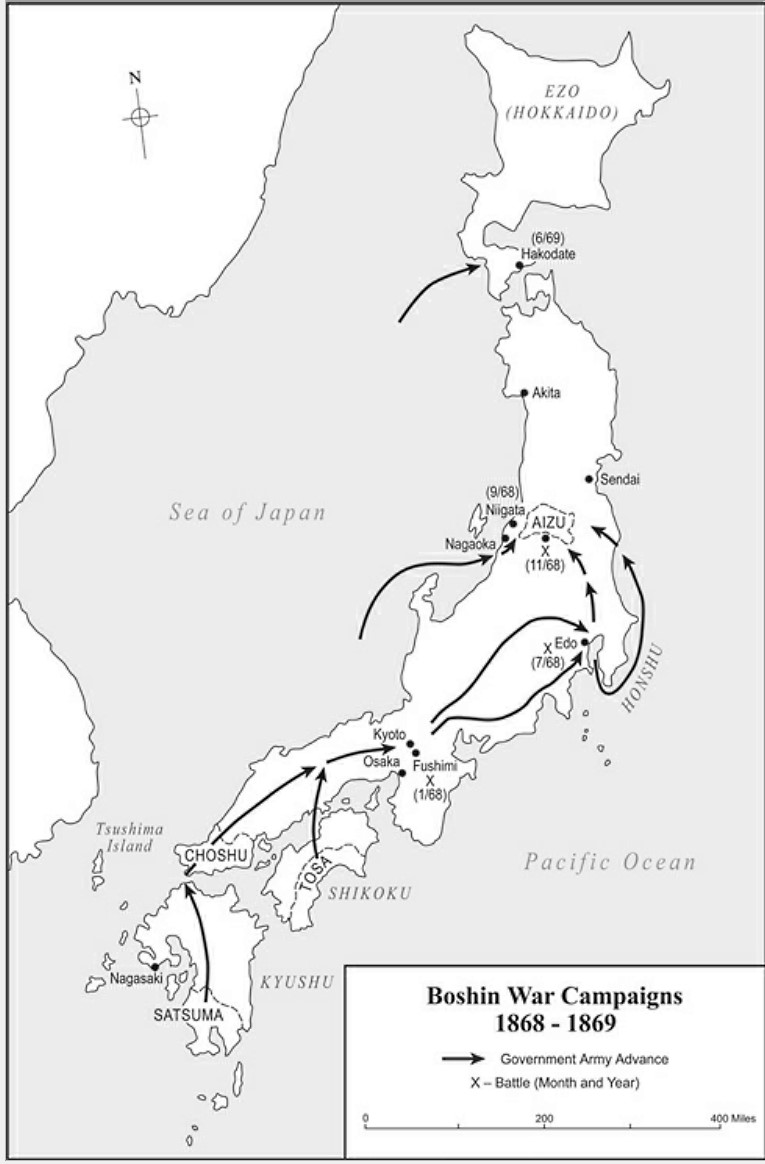

Meanwhile, in mid-March 1868 Prince Arisugawa took command

of the Eastern Expeditionary Force as loyalist columns pushed along three main

highways toward the shogun’s capital at Edo (present-day Tokyo). Skirmishes

involving a few hundred warriors on either side brushed aside bakufu

resistance, and the columns swiftly converged on the capital. The advancing

army continually proclaimed its close bond with the imperial court, first to

legitimize its cause; second, to brand enemies of the government as enemies of

the court and therefore traitors; and third, to gain popular support.

For food, supplies, horses, and weapons, the government army

established a series of logistics relay stations along the three major

thoroughfares. These small depots stocked material supplied by local

pro-government domains or confiscated from bakufu agencies, senior retainers of

the old regime, and anyone opposing the government. The army routinely

impressed local villagers as porters or teamsters to move supplies between the

depots and the frontline units. Japan’s largest merchant families also

contributed money and supplies to the new army. The Mitsui branch directors in

Edo, for example, donated more than 25,000 ryō (US$25,000) as insurance to

protect their storehouses from pro-bakufu arsonists and probably government

troops as well.

Government propaganda teams accompanied the army to extol the new imperial government’s virtues and to attract adherents by offering an immediate halving of taxes on rice harvests. To complement the effort, the army issued regulations governing conduct. All ranks would share the same food, accommodations, and work details; troops would immediately report anyone spreading rumors that might lower morale; quarreling and fighting in camp were forbidden; attacks against foreigners were strictly prohibited; and commanders were supposed to prevent arson, plunder, and rape from tarnishing the new government’s image. The results were mixed. If the populace cooperated, they were treated fairly, which meant the men might be persuaded to work as military porters or laborers, the villages to donate food, and promises made to cooperate with the government army. But the standard tactic to combat the roving bands of Tokugawa supporters who harassed government columns with hit-and-run attacks was to burn nearby homes to deny the guerrillas shelter. Suspected collaborators were summarily executed.

As the government troops pushed into bakufu strongholds, coercion replaced persuasion. Soldiers requisitioned food; confiscated weapons, valuables, and cash; and impressed villagers for labor details. Although government orders prohibited arson, it was an effective tactic during battle and for pacification purposes. Uncooperative villages risked being burned to the ground, likely because soldiers understood that inhabitants feared arson above all other forms of retribution. In extreme cases, such as the final northeastern campaign, government troops torched more than one-third of the homes in the Akita domain. To avoid that fate, villagers along the army’s route-of-march provided commanders with food, supplies, and intelligence. But this cooperation was based on little more than extortion and did not indicate a sudden shift in allegiance to the new government.

By the time the main loyalist forces reached Edo in early

May, Saigō Takamori had already negotiated a peaceful surrender of the city

with bakufu agents, the shogunate being divided internally between hard-liners

and those favoring an accommodation with the new government. The 41-year-old

Saigō stood almost six feet tall and weighed about 250 pounds, making him a

giant by Japanese standards. After a decade as a minor provincial official, in

1854 Saigō moved to Edo to promote Satsuma policies. Four years later

reactionary shogunate officials forced him to flee to Satsuma, but he was then

exiled. After his pardon in 1864, Satsuma officials sent Saigō to Kyoto to

handle the domain’s national affairs.

There was no denying Saigō’s ability, but the man was an

enigma, given to lengthy silences that could be interpreted as contemplative

wisdom or hopeless stupidity. His indifference to awards, honors, or material

trappings, complemented by his dynamic charisma and humanism, made Saigō the

most respected personality in early Meiji Japan. His deal with the bakufu,

however, had enabled more than 2,000 warriors loyal to the shogun to escape

from Edo, and the guerrilla war these reactionaries were waging against the

loyalists was ravaging the nearby countryside.

North of Edo pro-bakufu forces held Utsunomiya castle; in

early June, government forces defeated the shogun’s troops in a series of minor

engagements between Utsunomiya and Edo. They withstood a subsequent bakufu

counteroffensive and, strengthened with reinforcements, occupied the castle to

secure the northern approaches to Edo. The vanquished bakufu units fled to

northern Japan.

Meanwhile, loyalist troops had garrisoned the shogun’s

capital without opposition, but their efficiency and morale slowly

disintegrated as the provincial troops settled in to the comforts and fleshpots

of the big city. As martial skills eroded, Saigō worried about the diehard

pro-shogun radicals who retained de facto control of the city. The most

powerful of these bands was the Shōgitai (League to Demonstrate Righteousness),

formed in February 1868, which eventually enrolled about 2,000 warriors, each

sworn to kill a Satsuma “traitor. ”

Operating from its headquarters in Edo’s Ueno district,

Shōgitai units selectively cracked down on the roving criminal gangs that had

turned the nighttime capital into a place of robbery, murder, and extortion.

Besides punishing these outlaws they also ferreted out Satsuma informers and

pro-court spies, and while the government army slipped into idleness, Shōgitai

units busily constructed strongholds around Ueno Hill. The ongoing fighting in

the north and the deteriorating conditions in Edo created the impression that

the new government was unable to control the strategically vital Edo region.

When reports of the impasse in Edo reached the Kyoto government, leaders Ōkubo

Toshimichi (with Saigō a central leader of Satsuma since 1864), Kido Koin

(leader of Chōshū with Takasugi from 1865), and Iwakura Tomomi (a high-ranking

court noble) sent Ōmura Masujirō to restore government control in the city and

eliminate the Shōgitai influence.

Compared to Saigō, Ōmura seemed physically clumsy; and,

unlike the gregarious Saigō, his introverted personality and perpetually sour

countenance attracted few friends, much less casual admirers. Saigō’s patient

wait-and-see style and measured diplomacy left Ōmura seething at the sight of a

seemingly powerless government army standing idly by while the Shōgitai incited

antigovernment violence in Edo. Ōmura demanded action, but Saigō’s

disinclination to turn the city into a battleground was a major reason for his

lenient terms with the shogun’s representatives.

Assured from Kyoto that reinforcements and money were on the

way, Ōmura and his lieutenant Eto Shimpei decided to attack. They believed that

the Shōgitai were few in number and ignored Satsuma commanders’ arguments that

more loyalist troops were needed to stabilize the city. Moreover, Ōmura was

certain that his artillery would rout the pro-shogunate forces. His only

concession was to the weather; he postponed the offensive until the arrival of

the rainy season rather than bombard the city during the dry weather, when

Edo’s wooden buildings would burn like tinder.

On July 4 Ōmura summoned Saigō and ordered him to attack the

Shōgitai’s Ueno strongpoint immediately, overriding Saigō’s objections with a casual

wave of his fan. As Saigō and his captains had predicted, the attack ran

headlong into a ready-and-waiting enemy, the Shōgitai having been alerted to

the impending assault by Satsuma deserters. Although outnumbered two to one,

the approximately 1,000 Shōgitai troops fought from behind well-prepared

defenses that were anchored by a small lake on one flank and thick woods on the

other and could only be taken by a frontal assault.

Ōmura expected that artillery fire would drive the Shōgitai

from their shelters, leaving them vulnerable to Saigō’s infantry. From Edo

castle, Ōmura watched the billowing smoke and heard the loud explosions and

thought that his plan had succeeded. But the artillery guns soon malfunctioned,

and the few that did fire were wildly inaccurate, producing noise and fireworks

but few enemy casualties. Saigō’s vanguard, led by Kirino Toshiaki, charged

directly into the Shōgitai’s barricades, losing at least 120 men killed or

wounded. About twice that number of Shōgitai supporters were slain, although

many more were apprehended fleeing from Ueno.

The victory secured Edo for the new government, crushed one

of the largest and most violent antigovernment units, restored the momentum of

the imperial forces by releasing them to move north, and, by showing that the

pro-Tokugawa forces could not defeat the emperor’s army, calmed fears of a

prolonged civil war. Despite the artillery fiasco and the heavy government

casualties, Ōmura emerged as a hero, acclaimed for his grasp of modern military

science, much to Saigō’s chagrin, who had lost face over the incident.

Formidable resistance continued in northern Japan, but by controlling Edo the

army had turned a corner. To signify the bakufu’s demise, the next month the

capital moved from Kyoto to Edo, which had been the de facto political center

of Japan for 250 years. On September 3 Edo was officially renamed Tokyo, and

the next month Emperor Mutsuhito adopted the reign name of Meiji and henceforth

was identified as the Emperor Meiji.

The Northern Campaigns

On June 10, 1868, two Aizu samurai attacked a senior Chōshū

officer in a Fukushima brothel. Desperate to escape, he jumped through a

second-floor window only to land face-first on a stone walkway, where he was

seized by his assailants and later executed. Among the murdered official’s

personal effects were confidential government plans to subjugate the northern

domains, including the Tokugawa stronghold of Aizu. Reacting to these threats,

twenty-five pro-bakufu vassals in northern Honshū formed a confederation to

resist the Satsuma-Chōshū government, as distinct from the imperial government.

To crush the league, Ōmura devised a complicated strategy to capture the city

of Sendai on the Pacific (east) coast and then send converging columns

southward to attack the Aizu rebel stronghold at Wakamatsu castle from the

rear. Landings in Echigo Province on the Japan Sea (west) coast with probing

attacks against the major passes would fix the defenders in place.

Yamagata Aritomo commanded the 12,000-man-strong government

army contingent that landed along the west coast in late July and quickly

captured Nagaoka castle. Then he hesitated, even though his veteran forces

(leavened with about 1,000 kiheitai and Satsuma warriors) outnumbered the

rebels three to one. Yamagata spread the entire army along a 50-mile-long

defensive front, leaving him no reserve. He parceled out artillery, giving each

unit a few guns but not enough firepower to blast through league

fortifications. When he tried to evict rebel defenders from strategic mountain

passes, the army suffered successive reverses. Thereafter the rainy season made

streams and rivers impassable and restricted campaigning. By that time,

Yamagata was barely on speaking terms with his second-in-command, the veteran

Satsuma commander Kuroda Kiyotaka, who spent much of the campaign sulking in

his tent.

The opposing armies faced each other about 6 miles north of

Nagaoka, with their flanks bounded on the west by a river and on the east by a

large trackless swamp. Stuck in their cold, wet trenches, morale among

government troops plummeted, abetted by rebels chanting Buddhist funeral sutras

throughout the night. Meanwhile, battle-hardened, aggressive pro-Tokugawa

commanders executed an active defense, probing and raiding government outposts

and disrupting their rear supply areas.

On the east coast, operations initially went smoother. The

main government army moved overland from Edo on Shirokawa castle, which

dominated a strategic mountain pass leading to Aizu. By mid-June government

troops had taken the castle in a frontal attack coordinated with columns

enveloping the town. Government artillery destroyed the prepared defenses and

routed the 2,500 defenders. Several smaller domains in the league promptly

capitulated. The hardcore Aizu defenders withdrew into their main defenses,

which were constructed to blend into the rugged mountainous terrain. With

Yamagata’s western campaign stalled, there was little pressure on the Aizu

rear, enabling the rebels to concentrate their forces against the eastern prong

of the government offensive. The Kyoto high command sent reinforcements under

Saigō’s leadership to reinvigorate Yamagata’s operations.

Unable to break into the southern approaches to

Aizu–Wakamatsu castle, government troops commanded by Itagaki Taisuke and

Ichiji Masaharu maneuvered north along the main highway and in mid-October

captured the northern outposts protecting Aizu’s rear areas. They then pivoted

west through the mountains and defeated successive Aizu contingents by

concentrating artillery fire to pin down defenders while small bands of

riflemen turned their flanks. When the rebels shifted troops to protect their

vulnerable flanks, loyalist forces smashed through the weakened ridgeline

defenses. By late October Itagaki and Ichiji were within five miles of

Wakamatsu castle.

Around the same time, Saigō seized Niigata city, a major

port on the Sea of Japan about forty miles north of Nagaoka castle. Capturing

the port cut off rebel access to imported foreign-manufactured weapons and

interdicted a major supply route running from the city to Aizu-Wakamatsu. But

the day Niigata fell, rebel troops farther south capitalized on their knowledge

of the local terrain to cross the supposedly impassable swamp, outflank the

main government lines, and then overwhelm the small government garrison at

Nagaoka castle. With government forces divided and their line of communication

threatened, Yamagata fled for his life, allegedly discarding his sword and

equipment in his haste. Saigō countermarched south and retook the castle five

days later. Yamagata, however, failed to cut off the withdrawing rebel forces,

and the western campaign stalled again.

These setbacks and the slow progress on the eastern front

sowed doubt among government leaders in Kyoto that the army could finish the

campaign before the region’s heavy winter snows made further campaigning

impossible. Satsuma troops, which formed the backbone of the army, came from

southern Japan and were neither acclimated nor equipped for winter operations.

Rather than risk the imperial army’s carefully crafted reputation for

invincibility and its best troops, Ōmura suspended eastern operations against

Aizu until the following spring.

Itagaki and Ijichi ignored Kyoto’s orders and unilaterally

assaulted the main Aizu stronghold, forcing the heavily outnumbered Aizu

samurai to commit their entire reserve. One such unit, the White Tiger Brigade,

consisted of a few hundred 16- and 17-year-olds and suffered severe losses.

Retreating toward Wakamatsu castle, sixteen survivors mistakenly assumed that

the thick black smoke and red flames rising from the adjacent castle town meant

the castle had fallen. With all hope apparently lost, they committed suicide,

an act of sincerity that redeemed their treason and apotheosized the White

Tiger Brigade as a symbol of loyalty and selfless courage that resonated

powerfully among the public.

Once the main Aizu defenses collapsed, the army overran

minor strongholds in rapid succession and rebel survivors fled to Wakamatsu

castle. Although the government artillery could not penetrate the thick castle

walls, the defenders were unprepared for a winter siege and surrendered in

early November. Losses of pro-Tokugawa forces for the entire campaign were

around 2,700 killed. Sporadic fighting continued in northern Japan until

mid-December, when the league finally capitulated and its leaders took

responsibility for defeat by committing ritual suicide.

During the Tokugawa period suicide to atone for mistakes or

defeat was an accepted cultural norm among the warrior class. During the Boshin

Civil War warrior customs regarding fallen enemies or prisoners likely

encouraged battlefield suicides. Both armies routinely cut off the heads of

dead or wounded enemies for purposes of identification or morale-enhancing

displays. In one case a bakufu leader’s severed head was brought to Kyoto for

public display. The gruesome practice was widespread, and western doctors

working in Japan reported that they rarely saw wounded enemy soldiers,

apparently because of the criteria for head-taking and surrender.

Surrender was recognized, provided both sides agreed on

terms for capitulation. During the Boshin War’s early stages, potential

prisoners were usually executed for suspected cowardice for surrendering (the

idea of the shame of surrender) or because their wounds testified that they had

resisted government troops. Suspected spies or bakufu agents were summarily

executed. Many Shōgitai prisoners captured at Ueno fit all categories and were

promptly beheaded. In the later stages of the war, the new army accepted

surrenders of pro-bakufu troops as the government realized that reconciliation

was necessary to unify the nation.

This conciliatory attitude did not carry over to the

disposition of the dead. The government honored its war dead with special

ceremonies that Ōmura later institutionalized by establishing the Shōkonsha

(shrine for inviting spirits) in June 1869 as the official shrine to

commemorate government war dead. He hoped that official memorialization of the

war dead would stimulate a popular national consciousness by enshrining the

concept of an official death for the sake of the nation, not merely a private

death in a meaningless vendetta.

Enemy dead were regarded as traitors and ineligible for

enshrinement in government shrines. Their beheaded corpses were often left

where they fell, and local villagers would furtively bury the remains. Partly

because the Aizu warriors had so fiercely resisted the government army and

partly owing to Aizu’s long-standing enmity with Chōshū, the Meiji leaders

forbade even the burial of Aizu corpses and ordered them left to rot in open

fields.

At the end of 1868, Tokugawa supporters still controlled

Ezochi (Hokkaidō). In October 1868, bakufu ground and naval units from Sendai

had landed on Hokkaidō’s south coast and overwhelmed the undermanned army

garrison. The remaining government troops abandoned the island, fleeing to the

safety of nearby Honshū. In the spring of 1869, reconstituted and

much-strengthened government ground and naval forces returned and converged on

the major rebel stronghold at Hakodate. The outnumbered pro-shogunate rebels

fell back and by early May prepared for a final stand from Hakodate’s

pentagon-shaped fortress.

Constructed by the bakufu between 1857 and 1864 to protect

Ezochi from the Russian threat, the first western-style fortress in Japan

defended Hakodate’s harbor, where the three remaining bakufu warships were

sheltered. During naval battles on May 11, one government ship sank after a

shell exploded its powder magazine, but two bakufu warships ran aground, and

the third was previously damaged. The subsequent fighting for the fortress

produced more sound and flash than bloodshed. Thousands of government artillery

shells fell on the fortress, causing three casualties. Government losses were two

dead and twenty-one wounded. The siege did reduce the rebels to near

starvation, forcing them to surrender on May 25.