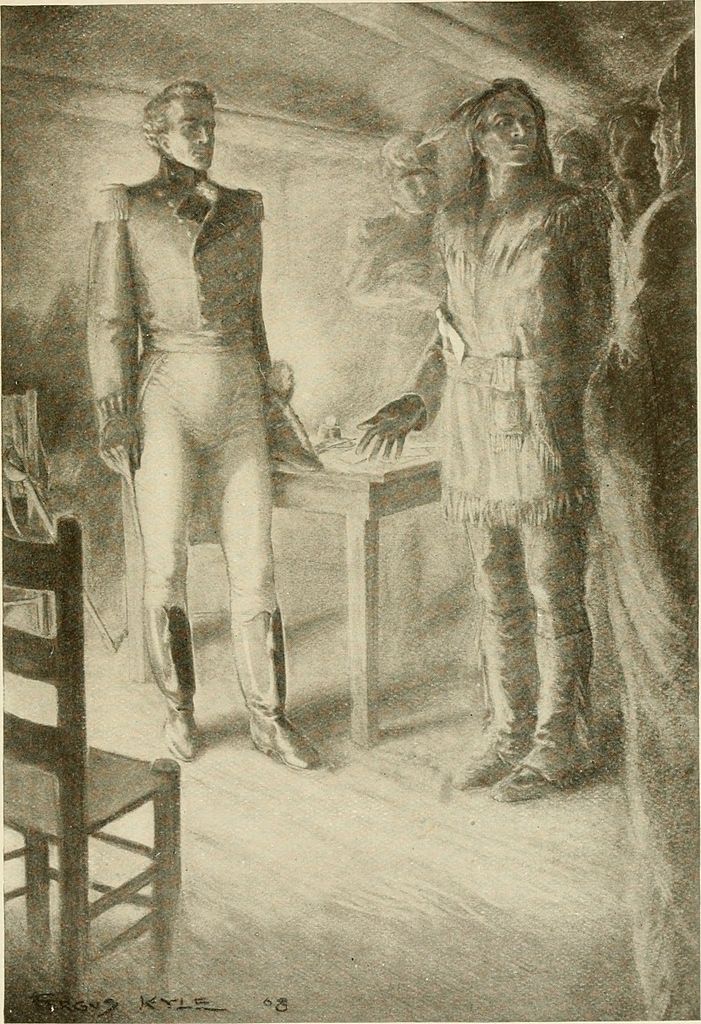

Major General Isaac Brock met with Shawnee chief Tecumseh in Amherstburg, Ontario and quickly established a rapport, ensuring that he would cooperate with his movements.

“Where today are the Pequot? Where the Narraganset, the

Mohican, the Pokanoket and many other once powerful tribes of our people? They

have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man, as snow

before a summer sun. . . .” So spoke the Shawnee chief Tecumseh in the early

years of the nineteenth century, exhorting his people – and the people of all

the eastern tribes – to make a final stand against the whites. He has been

called “the greatest Indian who ever lived.” And, indeed, he was the first

native leader with vision enough to see that if white encroachments were to be

stopped, the stopping could not be done by a single tribe, or even a

confederation, but only by a great union of all the tribes to fight for their

common homeland. He came too late to alter events, but he cast a long shadow

over the Indians’ last, desperate attempts to hold their lands east of the

Mississippi.

Tecumseh was born in 1768 near present-day Dayton, Ohio,

where the dispossessed Shawnees, buffeted by the Virginians on the east, the

Iroquois on the north, and the Creeks on the west, had finally found a home.

While still in his early teens, Tecumseh fought alongside the British in the

Revolution, and later he stood with Little Turtle against Harmar and the next

year St. Clair. He led raids against the border settlements until Anthony Wayne

came with his regulars, and then he fought bravely at Fallen Timbers, where he

lost a brother and witnessed the overwhelming defeat of his people.

Tecumseh refused to attend the subsequent council, which

ended with the piratical Greenville Treaty, and retired brooding into Indiana,

where he spoke against the white man and began to attract a following. Toward

the turn of the eighteenth century, he formed a strange friendship with a white

woman named Rebecca Galloway, the blonde, blue-eyed daughter of an Ohio farmer.

She taught him the Bible, Shakespeare, and world and American history. He

learned of Alexander the Great, Caesar, and other empire builders, and

certainly during this time, he pondered the efforts of Pontiac and King Philip

and the reasons they had failed. Eventually, he asked Rebecca to marry him, and

she consented on the condition that he abandon his Indian ways. Tecumseh

thought it over for a month, then refused and bade her farewell, telling her

that he could never leave his people.

About 1805, Tecumseh began to assert that no Indian tribe

had the right to sell lands to the white man without the consent of all the

tribes, and he gained a curious ally in Lalawethika, his indolent, drunken

younger brother. Lalawethika had led a dissolute life until he fell into a

trance from which he emerged insisting that he had communed with the Master of

Life. He changed his name to Tenskwatawa – “the Open Door” – and began to

preach the same message the Delaware Prophet had spoken in Pontiac’s time: shun

the white man’s liquor, abandon his ways, return to the old customs. The

reformed Tenskwatawa was so compelling a preacher that his word spread to

tribes as far away as the plains of central Canada. When, in 1808, he and

Tecumseh established a religious community on the Wabash near its confluence

with the Tippecanoe River, Delawares, Wyandots, Ojibwas, Kickapoos, and Ottawas

came to settle and live there in austere harmony.

In this village, which came to be called Prophetstown,

Tecumseh saw the nucleus of the great tribal union he hoped to forge. He left

it to roam the Northwest Territory and then the South, taking his message to

dozens of tribes. Many, cowed by the brutal reverses of the last decades,

scorned him, but others listened and took up the cause. Tecumseh was successful

enough that eventually General William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana

territory, became alarmed.

Then in his late thirties, the tough-minded Harrison was an

able soldier and a good administrator. He was also ambitious, and in the summer

of 1809, while Tecumseh was away proselytizing, he decided to take more Indiana

land from the Indians. Summoning some of the older chiefs to Fort Wayne, he

plied them with liquor and extracted from them the cession of 3 million acres

in return for $7,000 and a small annuity. When Tecumseh heard of this, his rage

apparently heightened his eloquence, for he soon had 1,000 warriors gathered in

Prophetstown to enforce his declaration that any attempt to settle the hastily

ceded land would be repelled.

Harrison did not underestimate his opponent. “The implicit

obedience and respect which followers of Tecumseh pay him,” he wrote, “is

really astonishing and more than any other circumstance bespeaks him one of

those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and

overturn the established order of things. If it were not for the vicinity of

the United States, he would perhaps be the founder of an Empire that would

rival in glory Mexico or Peru.”

With great caution, Harrison received Tecumseh at his

headquarters in Vincennes in August 1810. Arriving with 400 warriors, the chief

impressed at least one American officer, who wrote, “[Tecumseh] is one of the

finest men I ever met – about six feet high, straight with large fine features

and altogether a daring, bold-looking fellow.”

Harrison invited Tecumseh to take a chair among the

territorial officials gathered for the council, telling the Indian leader it

was the wish of the “Great Father, the President of the United States, that you

do so.” Tecumseh spurned the offer and stretched out on the ground, saying, “My

Father? – the Sun is my father, the Earth is my mother – and on her bosom I

will recline!”

During the next three days, Tecumseh recited his grievances

to Harrison, who found them “sufficiently insolent and his pretensions

arrogant.” When Harrison foolishly tried to placate his knowledgeable guest by

speaking of the “uniform regard to justice” shown the Indians by the whites,

Tecumseh jumped to his feet. “Tell him he lies!” he shouted to the interpreter,

while his warriors rose to stand around him.

“Those fellows mean mischief, you’d better bring up the

guard,” an official told a lieutenant, who ran to summon reinforcements.

Tecumseh urged the reluctant translator to relay his message. When Harrison

finally learned that he was being called a liar, he leaped to his feet and drew

his sword, while the regulars closed ranks behind him. The tension of the

moment ebbed, and Tecumseh later apologized, but the talks ended in an angry

stalemate.

“Is one of the fairest portions of the globe,” Harrison

asked the Indiana legislature, “to remain in a state of nature, the haunt of a

few wretched savages, when it seems destined, by the Creator, to give support

to a large population, and to be the seat of civilization, of science, and of

true religion?” When, in July 1811, Potawatomis killed some settlers in

Illinois, Harrison saw an opportunity to make a show of force and acted

quickly. Claiming that the murderers were followers of Tenskwatawa, he demanded

that the Shawnees in Prophetstown turn them over to him immediately. Tecumseh

refused and at once set out again to try to rally the southern Indians for the

fight he knew was imminent.

In an extraordinary six-month journey, he visited the

Carolinas, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, and Arkansas, begging the

natives to abandon their petty tribal squabbles and join together to fight for

their land while they still had land to fight for. Captain Sam Dale, a

Mississippi Indian fighter, heard Tecumseh speak and was astonished by the

chieftain’s eloquence; “His eyes burned with supernatural lustre, and his whole

frame trembled with emotion. His voice resounded over the multitude – now

sinking in low and musical whispers, now rising to the highest key, hurling out

his words like a succession of thunderbolts. . . . I have heard many great

orators, but I never saw one with the vocal powers of Tecumseh.” But for all

his vocal powers, Tecumseh met a great deal of resistance; the younger warriors

tended to support him, but the older chiefs, many of whom lived on government

annuities, held back.

In the meantime, Harrison hoped that before Tecumseh

returned “the fabrick which he considered complete will be demolished and even

its foundations rooted up.” In the fall of 1811, word came that Indians had

stolen the horses of an army dispatch rider. This was the incident Harrison

needed as an excuse to strike at the Indian community, and he put 1,000 men on

the march at once.

As the general moved with his army up the Wabash toward

Prophetstown, emissaries of Tenskwatawa stepped from the forest and asked him

for a council on the next day, November 7. Harrison agreed and went into camp

on Burnet’s Creek, three miles from the mouth of the Tippecanoe River. Uneasy

about Tenskwatawa’s intentions, he ordered his men to sleep on their arms,

bayonets fixed and cartridges ready.

Tecumseh had told his brother to avoid a fight until he

returned from the South, but with Harrison’s army a few miles away, Tenskwatawa

prepared to attack. He assured the Indians that, due to his magic, the white

men would be as harmless as sand, and their bullets as soft as rain. In fact,

he said, many of the whites were already dead. The confident Indians left

Prophetstown bent on that rarity in Indian warfare, a night attack. They

approached the American camp through a fine rain.

At quarter to four on the morning of November 7, one of

Harrison’s sentries saw something stirring off in the darkness. He had time to

get off a shot before the Indians killed him. The camp came awake to terrifying

shouts and a fusillade of musketry that tore into the tents and kicked the

campfire coals high in the air. In seconds, the Indians had broken the army’s

lines in two places. “Under these trying circumstances,” wrote Harrison, “the

troops (nineteen-twentieths of whom had never been in action before) behaved in

a manner that never can be too much applauded.” Surprised and frightened as

they were, men stood their ground, and companies stuck together even after

their officers had been killed. Dashing along the line, Harrison saw a young

soldier taking aim. “Where’s your captain?” he demanded.

“Dead, sir.”

“Your lieutenant?”

“Dead, sir.”

“Your ensign?”

“Here, sir,” the boy replied. Harrison told him to hang on,

and he turned to rally the militia. Subsequently, Harrison’s voice, according

to one admiring regular, “was frequently heard and easily distinguished, giving

. . . orders in the same calm, cool, and collected manner . . . which we had

been used to . . . on a drill on parade. The confidence of the troops in the

General was unlimited. . . .”

That confidence began to tell. Though the well-disciplined

Indians came on again and again, Harrison’s lines stiffened and held, and they

stood intact when daybreak brought the attacks to a halt. Tenskwatawa’s men

kept up a sporadic fire on the camp all day long, but that night, they went

away, too demoralized even to return to their village.

On November 8, the army entered Prophetstown, took what

supplies the men could carry, burned the rest, and started home. Harrison lost

thirty-seven dead and 150 wounded in the Battle of Tippecanoe, but he had

gained what he set out to gain, and more – thirty years later, the victory

would supply him with a campaign slogan that would put him in the White House.

Tecumseh returned early in 1812. Enraged at his brother for

triggering the premature fight, he threatened to kill him and then sent him

away. Tenskwatawa drifted west and soon dropped into obscurity. Taking stock of

the debacle, Tecumseh realized that what he had worked to prevent would now

begin: Isolated tribes would seek vengeance one by one, and with no unifying

force behind them, they would be easy targets for the army. Standing in the

ashes of Prophetstown, Tecumseh said, “I summoned the spirits of the braves who

had fallen . . . and as I snuffed up the smell of their blood from the ground I

swore once more eternal hatred – the hatred of an avenger.”

But Tecumseh could no longer wreak his vengeance, as he had

wished, at the head of a host of unified tribes. He needed an ally. And so,

reluctantly, he turned to the Canadian garrisons where the British were getting

ready for their second war against the Americans.

Though singularly unprepared for any sizable conflict, the

United States declared war on June 18, 1812. A month later, Brigadier General

William Hull marched out of Detroit with 2,200 men to invade Canada. Hull had

been a daring and capable officer during the Revolution, but now he was slow,

nervous, and, some said, senile. As Hull moved cautiously forward, Tecumseh

harried his flanks with Wyandot, Chippewa, and Sioux warriors who had been

drawn to the British cause by the magic of the chief’s name. Hull, frightened

by Tecumseh’s minor prods, hurried back to Detroit, where he soon found himself

besieged by Tecumseh and by British troops under Major General Isaac Brock.

Brock, a pleasant and capable officer, fully appreciated Tecumseh’s abilities

and took the Indian’s advice over that of his own officers when the chief

suggested an immediate attack on Detroit.

Hoping to convince Hull that thousands of warriors were

lurking in the forest, Tecumseh marched his force of 600 Indians three times

through a clearing in sight of the fort. Always ready to believe the worst,

Hull fell for the ruse. On August 16, without putting up any fight at all and

without consulting his officers, the frightened old commander surrendered

Detroit to a force less than half the size of his own.

For a brief, triumphant time, Tecumseh, his band of Indians

grown to 15,000, ravaged the Northwest, snatching up American outposts. But two

events soon dimmed the chief’s fortunes: In October, his friend and ally

General Brock fell to an American bullet, to be replaced by the far less able

Colonel Henry Proctor, and General William Henry Harrison took charge of a

force forlornly named “the second Northwestern Army.” With 1,100 men, Harrison

marched to recapture Detroit, and on his way, he built Fort Meigs near the site

of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Tecumseh learned to his dismay what sort of

man had succeeded Brock when the two of them went to attack Fort Meigs in the

spring of 1813. Colonel Proctor was as cautious as Hull and harbored a

wholehearted contempt for Indians.

When Fort Meigs failed to surrender immediately, Proctor

chose to invest rather than storm it, allowing time for 1,100 Kentucky

reinforcements to come up. Tecumseh’s warriors killed half of them, but

Proctor, disheartened, lifted his siege a couple of days later. Late in July,

Proctor decided he had had enough of campaigning, and, to Tecumseh’s immense

disgust, withdrew his forces to Fort Maiden on the Canadian side of the Detroit

River. This was a wonderful stroke of luck for Harrison, who needed time to get

his army organized. By September, he had 4,500 men waiting to move on the word

that Naval control of Lake Erie was in friendly hands, and the British thereby

cut off from their eastern supply bases.

Word came on September 10 in the form of a grubby note sent

by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry from the deck of his flagship: “DEAR GENL: We

have met the enemy, and they are ours – two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and

one sloop.” Proctor, who had also heard about the battle, decided to abandon

Fort Maiden and retreat.

Tecumseh had something to say about that: “You always told

us you would never draw your foot off British ground; but now, father, we see

you are drawing back. . . . We must compare our father’s conduct to a fat

animal, that carries its tail upon its back, but when afrighted, he drops it

between his legs and runs off. . . .” But though he could not shame Proctor

into holding the fort, Tecumseh did persuade the colonel to make a stand on the

Thames River, some eighty-five miles to the east. When they got there, with

Harrison following close behind, Proctor was again vacillating. While the

colonel faltered, Tecumseh chose a defensive position with the river on his

left flank and a swamp on the right. When the dispositions had been made, the

chief passed down the line, touching the hands of the British officers as he

went. “[He] made some remark in Shawnee,” one of them remembered, “which was

sufficiently understood by the expressive signs accompanying, and then passed

away forever from our view.”

Harrison attacked on the morning of October 5, sending his

cavalry headlong against the British line, a measure, he admitted, “not

sanctioned by anything I had seen or heard of but I was fully convinced it

would succeed.” It did. The British lines disintegrated, but the Indians,

posted in the swamp, poured out a volley that forced the Americans to dismount

and come in after them on foot. Above the clamor of the frenzied hand-to-hand

fighting, the soldiers heard Tecumseh roaring encouragement to his men. A few

saw him, blood on his face, defending his hopeless vision to the last. Then he

was gone, and soon after his Indians broke and fled.

That evening, some vengeful Kentuckians stripped the skin

from a body they thought was Tecumseh’s. They were wrong; his body was never

found. Later, a few of the chieftain’s followers said that they had carried the

corpse off the field and buried it secretly. For years, some believed that

Tecumseh still lived, and in a sense, they were right. Although Indian hopes

for holding the Northwest had died with Tecumseh, he had spread his word in the

South more effectively than he knew. Even while he was making his last stand on

the Thames, Indians 1,000 miles away who had been inspired by his rhetoric were

beginning a struggle that would last nearly thirty years.

Early in the 1800s, the Creeks lived in towns scattered

through Alabama and Georgia. Although many of them remained neutral when the

War of 1812 broke out, a remarkable chief named Red Eagle did not. Red Eagle

had been born William Weatherford, the son of a Scottish trader. Though only

one-eighth Indian, he chose to cast his lot with the Creeks and had been deeply

impressed by Tecumseh’s message. Late in August 1813, he led a war party

against Fort Mims on the lower Alabama River. The fort was little more than a

flimsy stockade built around the home of a man named Samuel Mims, who had given

shelter to some 500 settlers seeking refuge there from the threat of Creek

attacks.

On the morning of August 30, Major John Beasley, commanding

the garrison’s small force of Louisiana militia, had complacently left the main

gate open and neglected to post sentries. The major paid for his confidence

when, toward noon, Weatherford’s men leaped out of the tall grass and came

shouting toward the fort. Taken completely by surprise, the militiamen fought

back as best they could, struggling for hours under the blazing sun. At last,

with the house in flames from fire arrows, the defenders emerged to die at the

hands of the victors, who massacred all but thirty-six who managed to escape.

When word of the slaughter reached Tennessee, the

legislature there quickly authorized an army of 3,500 militia and $300,000 to

suppress the Creeks and turned to a tough, profane, brawling ramrod of a man

named Andrew Jackson to handle the job. Jackson was informed of the appointment

on his sickbed, where he was recovering from severe wounds sustained in a duel.

Though still too weak to get up, he said he would be on the march in nine days.

Pale, haggard, his arm in a sling, Jackson nevertheless drove his men south at

the rate of twenty miles a day. As the army approached Ten Islands on the Coosa

River, Jackson learned that 200 Creek warriors were staying in the nearby

village of Tallushatchee. He sent 1,000 men against the Indians, among them a

rangy young frontiersman named Davy Crockett, who reported with satisfaction

that “we shot them like dogs.” The militia lost five killed in the fight; the

Indians, 186.

Shortly afterward, word came that Weatherford was thirty

miles away, laying siege to Talladega, a Creek fort held by Indians loyal to

the United States. Jackson got his army on the march at once, and as his troops

approached the fort, the defenders waved and called out, “How-dy-do, brother,

how-dy-do.” There was little time for an exchange of pleasantries, however;

Weatherford’s men rushed from the woods, Crockett said, “like a cloud of

Egyptian locusts, and screaming like all the young devils had been turned loose,

with the old devil of all at their head.” The army made short work of them. In

fifteen minutes, a third of Weatherford’s 1,000-man force had fallen under

Jackson’s disciplined musketry. The rest would have been done for too, but they

had the good fortune to dislodge some shaky militia in the line and escaped

into the woods.

However satisfying the victory, it did not feed Jackson’s

ill-supplied troops, and late in November, the hungry, disgruntled soldiers

started home. Jackson, still weak from his wounds and ravaged with dysentery,

blocked their path and, bluffing with a rusted, useless musket, threatened to

shoot the first man who stepped forward. The troops stayed, and in January

1814, their nerveless commander had them marching south to Horseshoe Bend,

where the Tallapoosa River swings in a wide loop. Across the neck of this

peninsula, Weatherford’s Creeks had built a sturdy log barricade. By the time

Jackson arrived with 2,000 troops, 900 warriors stood ready to oppose him.

Jackson brought his artillery to bear on the position on the morning of March

27, but the shot sank harmlessly into the thick logs. Finally, the general

ordered a frontal assault, and he saw his men go forward into the teeth of

heavy fire and swarm across the barricade. The Indians fought stubbornly all

afternoon, but by nightfall, the troops had virtually annihilated the Creek

nation. More than 500 warriors lay dead, but Weatherford was not among them.

A few days later, a gaunt Indian, dressed in rags, appeared

in the army camp and approached Jackson. “I am Bill Weatherford.” he said.

Jackson took his visitor into his tent. “I am in your

power,” Weatherford told the general, “do with me as you please. I am a

soldier. I have done the white people all the harm I could; I have fought them,

and fought them bravely; if I had an army, I would yet fight, and contend to

the last: but I have none; my people are all gone. I can now do no more than

weep over the misfortunes of my nation.”

Moved, Jackson replied, “You are not in my power. I had

ordered you brought to me in chains. . . . But you have come of your own accord

. . . I would gladly save you and your nation, but you do not even ask to be

saved. If you think you can contend against me in battle, go and head your

warriors.”

Weatherford walked out of the camp a free man and never

fought again.

Jackson acquitted himself less honorably during the treaty

negotiations that followed. The Creeks came to the council so hungry, Jackson

said, that they were “picking up the grains of corn scattered from the mouths

of horses.” On these wretched people, the general forced a treaty by which they

gave up 23 million acres of their land. Though the Creeks would never again

fight as a nation, many of them moved south to Florida, where they settled among

the Seminoles, who also hated the whites.