Typhoon Louise Strikes

“Was it Louise,” asked one, “was it the October typhoon that

killed the plan?”

“Ultimately, yes. It had been a hard sell to begin with. The

shipping crisis that had come to a head at Leyte had never been completely

solved and there was a legitimate concern that if too much was lost during

Bugeye we would be hard-pressed to fulfill our needs during Majestic. We

received the go-ahead for Bugeye only after certain numbers of assault ships of

every category had been pulled from the operation. Vessels like the

thirty-eight to be used as blockships for Coronet’s ‘Mulberry’ harbor would

have been completely satisfactory for the feint, and yet though many were

virtual derelicts, we were nevertheless required to preserve them for Tokyo. I

need not remind you that construction of the artificial harbor carried a priority

second only to development of the atom bomb, and that we were producing seven

unique, heavy-lift salvage ships in two classes especially for the invasion. As

things turned out, four of the six that had arrived in-theater survived Typhoon

Louise and were fully employed with salvage operations at Okinawa till nearly

Thanksgiving.

“Everyone in this room is painfully aware of the disaster at

Okinawa. Every plane that could be gassed up was sent south [to Luzon] and most

were saved. The flat bottoms [assault shipping and craft designed to be

beached] weren’t so lucky. Six-hours’ warning was not enough. Shifting cargoes

in the combat-loaded LSTs sent sixty-one of 972 LSTs to the bottom; 186 of

1,080 LCTs went down or were irretrievably damaged; 92 of 648 LCIs—the list

goes on. Plus a half-dozen Liberty ships and destroyers. At least they couldn’t

blame this one on Bill. This storm took on mystical proportions to the Japanese

war leaders who had defied the Emperor and taken over the government when he tried

to surrender during the first four atomic attacks in August.” Harkening back to

the original “Divine Wind,” or kamikaze, that destroyed an invasion force

heading for Japan in 1281, they saw it as proof that they had been right all

along. Their industrial base in Manchuria was gone because of the Soviet

invasion, their cities were in ashes, but the Japs were even more certain that

we would sue for peace if they just held out.

“Any chance of carrying out the feint was gone. With a

little more time, the shipping losses—greater in tonnage than Okinawa—could be

made up. But there was no time. The Joint Chiefs originally set December 1,

1945, as the Kyushu invasion date with Coronet, Tokyo’s Kanto Plain, three

months later on March 1.

“What I’m about to say is an important point and I’ll be

returning to it in a moment. To lessen casualties, the launch of Coronet

included two armored divisions shipped from Europe that were to sweep up the

plain and cut off Tokyo before the monsoons turned it into vast pools of rice,

muck, and water crisscrossed by elevated roads and dominated by rugged,

well-defended foothills.

“Now, planners envisioned the construction of eleven

airfields on Kyushu for the massed airpower which would soften up the Tokyo

area. Bomb and fuel storage, roads, wharves, and base facilities would be

needed to support those air groups, plus our 6th Army holding a 110-mile stop

line one-third of the way up the island. All plans centered on construction of

the minimum essential operating facilities, but most of the airfields for heavy

bombers were not projected to be ready until ninety to 105 days after the

initial landings on Kyushu, in spite of a massive effort. The constraints on

the air campaign were so clear that when the Joint Chiefs set the target dates

of the Kyushu and Tokyo invasions for December 1, 1945, and March 1, 1946,

respectively, it was apparent that the three-month period would not be

sufficient. Weather ultimately determined which operation to reschedule,

because Coronet could not be moved back without moving it closer to the

monsoons and thus risking serious restrictions on all ground movement— and

particularly the armor’s drive up the plain—from flooded fields, and the air

campaign from cloud cover that almost doubles from early March to early April.

MacArthur’s air staff proposed bumping Majestic ahead by a month, and both my

boss, Admiral Nimitz, and the Joint Chiefs immediately agreed. Majestic was

moved forward one month to November 1.

“The October typhoon changed all that. A delay till December

10 for Kyushu, well past the initial—and unacceptable— target date was forced

upon us, with the Tokyo operation pushed to April 1—dangerously close to the

monsoons. We were going to get one run, and one run only, at the target. No Bugeye.

One of the greatest opportunities of the war had been lost.”

At first there were no hands appearing above the audience

since they were still absorbing everything that Admiral Turner had said. A navy

captain in the second row was the first to break the silence.

“Sir, was there reconsideration at this time of switching to

the blockade strategy that we, the navy, had been advocating since 1943?”

Turner’s host that evening, Admiral Spruance, had been

outspoken in his belief that such a move was the best course but, like Turner,

had followed orders to the fullest of his ability and beyond. Turner knew that

he had already said far more than he should on Bugeye and moved to wrap things

up.

“I can’t tell you what others were advocating. All I can say

is that I was fully, very fully, engaged in carrying out my orders. On a

personal note, I would have to say that I believe that the change in plans

regarding the use of atom bombs during Majestic was fortuitous. After the first

four bombs on cities failed in their strategic purpose of stampeding the

Japanese government into an early surrender, the growing stockpile of atom

bombs was held for use during the invasion. Initially, though, we did not

intend to use them as they were eventually employed against Japanese formations

moving down from northern Kyushu. Initially we were going to allot one to each

corps zone shortly before the landings.”

Audible gasps and a low whistle could be heard from some in

the audience, who immediately recognized the implications of what the admiral

was saying.

“Yes,” Turner acknowledged “the radiation casualties we

suffered in central Kyushu were bad enough, but they were only a fraction of

what would have happened if we had run a half-million men directly into

radiated beachheads—and all that atomic dust being kicked up during the base

development and airfields construction! The result hardly bears thinking about.

It was clear, after the initial bombs in August, that the Japs were trying to

wring the maximum political advantage from claims that the atom bombs were

somehow more inhuman than the conventional attacks that had burnt out every

city with a population over 30,000. At first their claims about massive radiation

sickness were thought to be purely propaganda. However, over the next few

months it was determined that there was enough truth to what they were saying

to switch the bombs to targets of opportunity after the Jap forces from

northern Kyushu moved down to attack our lodgment in the south. They had to

concentrate before they could launch their counter-offensive, and that’s when

we hit ’em. As for the original landing zones, repeated carpet bombing by our

heavies from Guam and Okinawa produced the same results that the atom bombs

would have, and besides, the big bombers had essentially run out of strategic

targets long before the invasion. The carpet bombing gave them something to

do.” This remark elicited laughter.

“The Jap warlords were unmoved when atom bombs were employed

over cities, but the extensive use of the bombs against their soldiers is what

finally pushed them to the conference table. Yes, they changed their tune when

they faced the possibility of losing their army without an ‘honorable’ fight,

but so did we when it became undeniably clear that our replacement stream would

not keep up with casualties.”

Turner looked over at General “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, and

continued “One man in this room tonight served in the trenches of World War

One. An incomplete peace after that war meant that he and the sons of his

buddies had to fight another war a generation later. We can only pray that the

recent peace will not end in a bigger, bloodier, perhaps atomic, war with Imperial

Japan in 1965. Thank you.”

The Reality

The coup attempt by Japanese forces unwilling to surrender

was thwarted by Imperial forces loyal to Emperor Hirohito, and the Japanese

government succeeded in effecting a formal surrender before the home islands

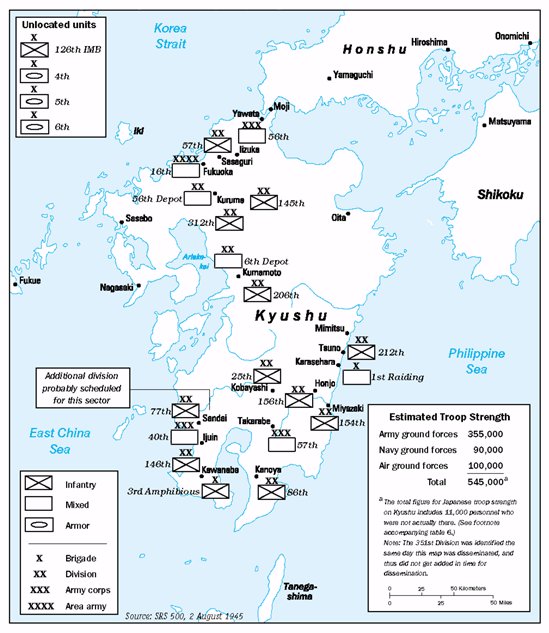

were invaded. Occupation forces on Kyushu were stunned by the scale of the

defenses found at the precise locations where the invasion was scheduled to

take place. The U.S. military government eventually disposed of 12,735 Japanese

aircraft.

On October 9-10, 1945, Typhoon Louise struck Okinawa.

Luckily, Operation Majestic had been canceled months earlier. There was

considerably less assault shipping on hand than if the invasion of Kyushu had

been imminent, and “only” 145 vessels were sunk or damaged so severely that

they were beyond salvage.

Bibliography

Asada, Sadao, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s

Decision to Surrender—A Reconsideration,” Pacific Historical Review 67,

November 1998.

Bartholomew, Charles A., Captain, USN, Mud, Muscle and

Miracles: Marine Salvage in the United States Navy (Department of the

Navy, Washington, D.C., 1990).

Bix, Herbert P., Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan

(Harper Collins, New York, 2000), 519.

Bland Larry 1. (ed.), George C. Marshall Interviews and

Reminiscences for Forrest C. Pogue (George C. Marshall Foundation,

Lexington, 1996).

Brown, Anthony Cave, Bodyguard of Lies, vol. 2 (Harper &

Row, New York, 1975).

Buell, Thomas B., The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral

Raymond A. Spruance (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 1987).

The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, vol. 1: Reports

of General MacArthur (General Headquarters, Supreme Allied Command, Pacific,

Tokyo, 1950).

Cannon, M. Hamlin, Leyte: The Return to the Philippines

(Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954).

Cline, Ray S., Washington Command Post: The Operations

Division (Department of the Army, Washington, DC, 1954).

Coakley, Robert W, and Leighton, Richard M., The War

Department: Global Logistics and Strategy, 1943-1944 (Department of the Army,

Washington, DC, 1968).

Coox, Alvin D, “Japanese Military Intelligence in the

Pacific: Its Non-Revolutionary Nature,” in The Intelligence Revolution: A

Historical Perspective (Office of Air Force History, Washington, D.C., 1991).

, “Needless Fear: The Compromise of U.S. Plans to Invade Japan in 1945,”

Journal of Military History, April 2000.

Drea, Edward J., MacArthur’s Ultra: Codebreaking and the War

Against Japan, 1942-45 (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1992).

Dyer, George Carroll, Vice Admiral, USN, The Amphibians Came

to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner (U.S. Navy Department,

Washington, D.C, 1972).

Frank, Bemis M., and Shaw, Henry I., Jr., History of U.S.

Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 5: Victory and Occupation

(Historical Branch, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 1968).

Gallicchio, Marc, “After Nagasaki: General Marshall’s Plan

for Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Japan,” Prologue 23, Winter 1991.

Giangreco, D. M., “Operation Downfall: The Devil Was in the

Details,” Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn 1995.

, “The Truth About Kamikazes,” Naval History, May-June 1997.

, “Casualty Projections for the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1946:

Planning and Policy Implications,” Journal of Military History, July 1997.

Hattendorf, John B.; Simpson, B. Michael, III; and Wadleigh,

John R., Sailors and Scholars: The Centennial History of the Naval War College

(Naval War College Press, Newport, Rhode Island, 1984).

Hattori, Colonel, The Complete History of the Greater East

Asia War (500th Military Intelligence Group, Tokyo, 1954).

Huber, Thomas M., Pastel: Deception in the Invasion of Japan

(Combat Studies Institute, Fort Leavenworth, 1988).

Inoguchi, Rikihei, Captain, UN, and Nakajima, Tadashi,

Commander, UN, The Divine Wind: Japan’s Kamikaze Force in World War II (Naval

Institute Press, Annapolis, 1958).

Interrogations of Japanese Officials, vol. 2 (United States

Strategic Bombing Survey, Tokyo, 1946).

“The Japanese System of Defense Call-up,” Military Research

Bulletin,no. 19, 18 July 1945.

Kendrick, Douglas B., Brigadier General, USA, Medical

Department,United States Army: Blood Program in World War II (Office of the

Surgeon General, Washington, DC, 1964).

Morison, Samuel Eliot, Rear Admiral, USN, History of United

States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 12: Leyte, June 1944–January 1945

(Little, Brown, Boston, 1958).

, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 13, The

Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas, 1944–1945 (Little,

Brown, Boston, 1959).

, History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 14:

Victory in the Pacific, 1945 (Little, Brown, Boston, 1960).

, The Two Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second

World War (Little, Brown, Boston, 1958).

Oil in Japan’s War: Report of the Oil and Chemical Division,

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Pacific (United States Strategic

Bombing Survey, Tokyo, 1946).

O’Neill, Richard, Suicide Squads: Axis and Allied Special

Attack Weapons of World War II, Their Development and Their Missions

(Ballantine Books, New York, 1984).

Potter, E.B., Nimitz (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis,

1976).

Roland, Buford, Lieutenant Commander, USNR, and Boyd,

William B., Lieutenant, USNR, U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance in World War II

(U.S. Navy Department, Washington, DC, 1955).

Sakai, Saburo; Caidin, Martin; and Saito, Fred, Samurai

(Bantam Books, New York, 1978).

Sherrod, Robert, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World

War II (Presidio Press, Bonita, 1980).

Stanton, Shelby L., Order of Battle, U.S. Army, World War II

(Presidio Press, Novate, 1984).

Walker, Lewis M., Commander, USNR, “Deception Plan for

Operation Olympic,” Parameters, Spring 1995.