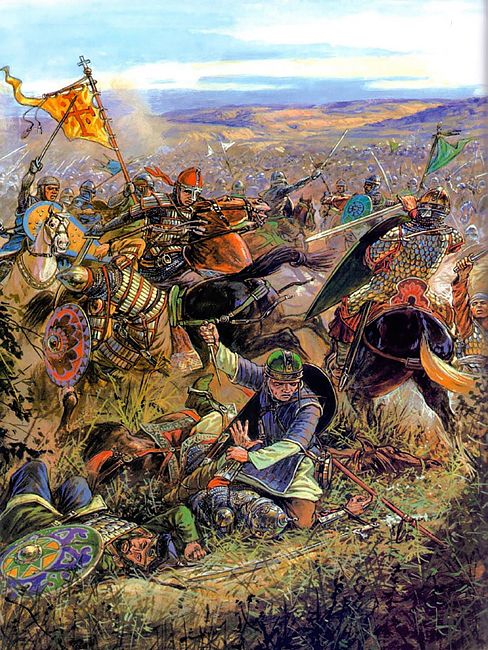

“Battle of Nicaea (1097)”, Igor Dzis

The first challenge

It was only on 15 May that the Franks found out why, when

two Turkish spies were caught in the Frankish camp masquerading as Christians.

One was killed during capture, but the other was immediately taken for

interrogation. Threatened with torture and death, he quickly confessed

everything. Kilij Arslan had returned from the east. Having finally realised

how dangerous the crusaders might be, he had gathered a large army from across

the sultanate of Rüm, and was even now camped in the steep hills to the south

of the city, planning a counterattack the very next day. Contact had already

been established with the Turks in Nicaea – hence their change of heart – and

these two spies had been sent to observe the Frankish army and then carry final

battle instructions to the garrison. Kilij Arslan’s plan was to charge out of

the southern hills at the third hour after dawn, enter Nicaea through the

unblockaded south gate, regroup and then launch an immediate combined

counterattack. Having told this story, the Turkish spy pleaded for his life,

weeping, begging and even offering to convert to Christianity should he be

spared, and eventually the princes took pity on him.

The princes reacted quickly to these shocking revelations.

They knew that Raymond of Toulouse and the Provençal army were already en route

to Nicaea, and were, at that very moment, perhaps less than a day’s march away

to the north, along the road from Nicomedia. As dusk approached, messengers

were dispatched urging haste, and the Frankish host kept nervous watch through

the night. Finally, at dawn on 16 May, Raymond’s men appeared out of the north.

The crusaders’ careful preparation of the old Roman road had paid off – news

had reached the Provençals quickly and they had then been able to march along

the clearly marked route through the night. In fact, Raymond of Toulouse

arrived just in time. His army was still in process of setting up camp before

Nicaea’s southern gate when, just as the spy had predicted, Kilij Arslan’s

forces came pouring out of the hills.

He had come prepared for victory – his men carried ropes

with which to bind the crusaders once they were taken captive – but, even

without the Provençal reinforcements, Kilij Arslan would have been hard pressed

to overcome the massive Latin army. With Nicaea’s southern gate blocked, his

troops were both outnumbered and isolated. He led an archetypal Seljuq Turkish

army: thousands of lightly mounted, fast-moving archers, armed with powerful

bone-and-horn composite bows. Faced with staunch resistance from the Provençals

led by Raymond and Baldwin of Boulogne, hemmed in by the lake to the west and

struck in the flank by Godfrey’s and Bohemond’s fierce cavalry charge from the

east, the Turkish attack soon faltered. Realising that he was hopelessly

outnumbered, Kilij Arslan fled the field south. It would be his only attempt to

break the siege of Nicaea. In the days that followed, the renegade Turkish spy,

whose predictions had proved to be accurate, went through a ritual of

conversion and became a regular guest of the Frankish princes, to whom he was

an intriguing curiosity. Soon his guards became relaxed in his company and in

one careless moment took their eyes off him. Instantly seizing the opportunity,

he ‘flew across the city moat with a nimble-footed leap’ and was soon pulled

over the walls on a rope.

In spite of this minor betrayal, the crusaders’ first battle

with a Muslim force had been a resounding success. Even Anna Comnena, not

usually given to praising the Franks, described it as ‘a glorious victory’. In

truth, although the crusader defence had been well co-ordinated, Kilij Arslan

escaped with most of his army intact. The real damage was done to his military

prestige and the morale of Nicaea’s garrison. In the aftermath of the fighting,

‘the Christians cut off the heads of the dead and wounded and as a sign of

victory they brought them back to their tents with them tied to the girths of

their saddles’. Some were stuck on the ends of spears and paraded before the

city walls, others were actually catapulted into the city ‘in order to cause

more terror among the Turkish garrison’. One Latin contemporary even suggested

that a thousand Turkish heads had been sent to Alexius as a sign of victory.

Any medieval army knew the profound significance of morale

amid the slow grind of siege warfare, and exchanges of horrific acts of

brutality and barbarism were commonplace. For its part, the Turkish garrison

soon retaliated, adopting a rather macabre tactic. The crusaders began to lead

direct assaults upon the city and inevitably sustained some losses. One Latin

eyewitness was disgusted by the Turks’ treatment of these dead: ‘Truly, you

would have grieved and sighed with compassion, to see them let down iron hooks,

which they lowered and raised by ropes, and seize the body of any of our men

that they had slaughtered in some way near the wall. None of our men dared, nor

could, take the body from them.’ These corpses were robbed and then hung from

the walls to rot, so as ‘to offend the Christians by this inhuman conduct’.

Closing in

With the first threat from Kilij Arslan repulsed, the

crusaders sought to prosecute a direct assault. This would be a dangerous and

exhausting process for defender and aggressor alike, and we hear that in the

midst of the fighting, ‘often, some of the Turks, often, some of the Franks,

struck by arrows or by stones, died’. When early attempts to storm Nicaea’s

defences with ladders had failed, the crusaders concentrated their efforts

almost exclusively upon creating a physical breach in the city’s walls. This

could be achieved through a variety of means. The safest, but technologically

most advanced, was bombardment from a distance. The Franks built some

stone-throwing machines, known as petraria or mangonella, which propelled

missiles through the use of torsion or counterweights. Powerful machines could

hurl massive rocks against their target, eventually causing walls to buckle and

collapse, but at Nicaea the crusaders lacked the skills and craftsmen to build

engines massive enough to damage the city’s stout walls. Their bombardment was

designed, instead, to harass the Turkish garrison and provide covering fire,

under which they could employ a second technique.

If a besieging army could not topple walls from a safe distance,

then the only alternative was to get in close and undermine the defences by

hand. Just approaching the walls was, however, a lethal affair. The Turkish

garrison had ballistae – giant crossbow-like devices used to hurl stones – and

archers with which to defend their city: ‘The ballistae of [Nicaea’s] towers

were so alternately faced that no one could move near them without peril, and

if anyone wished to move forward, he could do no harm because he could easily

be struck down from the top of a tower.’ One crusader knight, Baldwin of

Calderun, who had made many ‘daring and rash’ attempts to assault the city,

‘breathed his last when his neck was broken by the blow of a hurled stone’.

Another, Baldwin of Ganz, died during ‘a careless rush at the city, his head

pierced by an arrow’. If a crusader did, somehow, manage to reach the foot of

the walls alive, he then faced an onslaught from above, as defenders atop the

battlements gleefully rained rocks and a burning mixture of grease, oil and

pitch down upon his head.

The Franks experimented with a range of devices to combat

these problems of direct assault, with varying degrees of success. Two

prominent Latin lords, Henry of Esch, a member of Godfrey’s contingent, and the

German Count Hartmann of Dillingen, who had participated in the Jewish pogrom

at Mainz, approached the challenge of this first crusader siege with

enthusiasm. They pooled their resources and built what one contemporary called

a vulpus or fox, to their own design and with their own money. This was apparently

some form of bombardment screen, constructed of oak beams, under which infantry

troops could advance on the walls, protected from Turkish missiles. Henry and

Hartmann shrewdly decided to sit out the first test run of this contraption,

and had to look on in horror as twenty of their men were crushed to death when

‘the beams, the uprights and all the bindings came to pieces’ and the vulpus

collapsed at the foot of the walls.

The Provençals adopted a more professional approach. Raymond

of Toulouse employed a master craftsman to design and build a testudo or

tortoise, a much sturdier, sloping-roofed bombardment screen. Under this

protection, southern French crusaders were dispatched to undermine a tower on

Nicaea’s southern walls. One eyewitness described how, when they reached the

fortification, ‘sappers dug down to the foundations of the wall and inserted

beams and pieces of wood, to which they set fire’. If carried out correctly,

the siege technique they were attempting – that of sapping – could be extremely

effective. The idea was to dig a tunnel beneath a section of wall, carefully

buttressing the excavation with wooden supports as one went along. Once

complete, the void was packed full of branches and kindling, set alight and

left to collapse, thus bringing down the wall above it. Raymond’s sappers

managed to bring down a small section of one tower as night fell on around 1

June, but the Turkish garrison worked through the night to rebuild the defences

so that by daybreak ‘there was no chance of defeating them at that point’.

In the end, the crusaders’ best efforts at assault were

thwarted by Nicaea’s almost impregnable fortifications and the sheer energy and

ferocity of the Turkish defence. Even Raymond of Aguilers, a chaplain in the

Provençal army, was forced to admit that the Muslim garrison had made a

‘courageous’ effort. We hear, for example, of one unnamed Turkish soldier who

went berserk and continued fighting, peppered with twenty crusader arrows. Even

after 3 June 1097, when the Latin army was further strengthened by the arrival

of the northern French, under Stephen, count of Blois, and Robert, count of

Flanders, the city still refused to fall.

By the second week of June, the crusaders realised that a

new strategy was needed. Up to this point they had encircled Nicaea’s three

landward walls, but the fourth, westward face of the city, on the banks of the

great Askanian Lake, lay open and unblockaded. The sheer size of this lake

meant that its banks could not be effectively patrolled, and it became apparent

that Turkish boats were bringing all manner of supplies into Nicaea without

fear of attack. If this situation persisted and the city’s walls held, Nicaea’s

garrison might realistically hope to hold out indefinitely. Around 10 June, the

crusader princes met in council to discuss this problem, and within hours a

messenger had been sent to the Emperor Alexius, carrying an audacious proposal.

Control had to be taken of the Askanian Lake, but no navigable river offered

ships access to its waters. The princes’ solution sounded simple: if vessels

could not be sailed to the lake, they would have to be carried. In practice, of

course, the process of portaging large sailing boats almost thirty kilometres

from the coast at Civetot to the shores of the Askanian Lake was no mean feat.

Alexius agreed to supply the boats, under the command of Manuel Boutoumites and

manned by a force of Turcopoles – well-armed Byzantine mercenaries of

half-Greek, half-Turkish stock. Special oxen-drawn carts were constructed to bear

this strange cargo through the hills of Bithynia. Late in the day of 17 June

they reached the lake, but waited until the following dawn to set sail so that

a combined lake- and landbased attack could be launched on Nicaea. The plan was

to terrify the Turkish garrison into submission, driving home their isolation

and the utter hopelessness of continued resistance. To this end, Alexius

equipped the small Greek flotilla with more standards than were usual – so that

the boats might appear more numerous than they really were – and a selection of

trumpets and drums with which to create an intimidating racket. One Latin

eyewitness described the scene:

At daybreak there were the boats, all in very good order,

sailing across the lake towards the city. The Turks, seeing them, were

surprised and did not know if it was their own fleet or that of the emperor,

but when they realised it was the emperor’s they were afraid almost to death,

and began to wail and lament, while the Franks rejoiced and gave glory to God.

The shock broke the Turkish garrison’s will, and within hours they were suing for peace. After holding out for five weeks, Nicaea capitulated on 18 June. It was, however, the emperor’s men, Manuel Boutoumites and Taticius, who actually took surrender of the city and raised the imperial standard. After all their efforts, the crusaders were left waiting outside the walls. Byzantine Turcopoles were set to guard the city’s treasury and the crusaders were denied any chance of plunder. It was a precarious moment for Alexius’ envoys: they may have had nominal authority over the campaign, but they were outnumbered both by the barely subdued Turkish garrison inside the city and by the acquisitive Frankish horde without. Had either side chosen to rebel, the Greeks would have been annihilated. As it was, the crusader princes kept their promise to return the city to the emperor, and the leading members of the Turkish garrison were quickly ferried out in small, manageable groups to Constantinople. There were some complaints among the Latin rank and file, worried that the captured Turks would soon be ransomed and thus free to fight the crusaders on another day, but even these were quickly silenced by the emperor’s extravagant largesse. He knew only too well how to keep this ‘mercenary’ crusading army under control. One Frank recalled that, ‘because he kept all, the emperor gave some of his own gold and silver and mantles to our nobles; he also distributed some of his copper coins, which they call tarantarons, to the footsoldiers’.

The fall of Nicaea was a product of the successful policy of close co-operation between the crusaders and Byzantium. The Franks would probably have enjoyed little success without Greek aid, while Alexius had needed the might of the Latin army to overcome Kilij Arslan’s capital. One contemporary, reflecting upon the siege, wrote, ‘Now that the storm of war had thus abated . . . the army of the living God spent the day in great rejoicing and exultation right there in the camp, because everything so far had gone well for them’. Their success had, however, been bought at a price. Many crusaders died in battle or from illness during the campaign. An eyewitness in Bohemond’s army recalled that ‘many of our men suffered martyrdom there and gave up their blessed souls to God with joy and gladness, and many poor starved to death for the Name of Christ. All these entered Heaven in triumph, wearing the robe of martyrdom.’ Even at this early stage in the expedition to Jerusalem it seems that the crusaders believed that fighting and dying in the name of God cleansed them of sin and brought the gift of everlasting life.