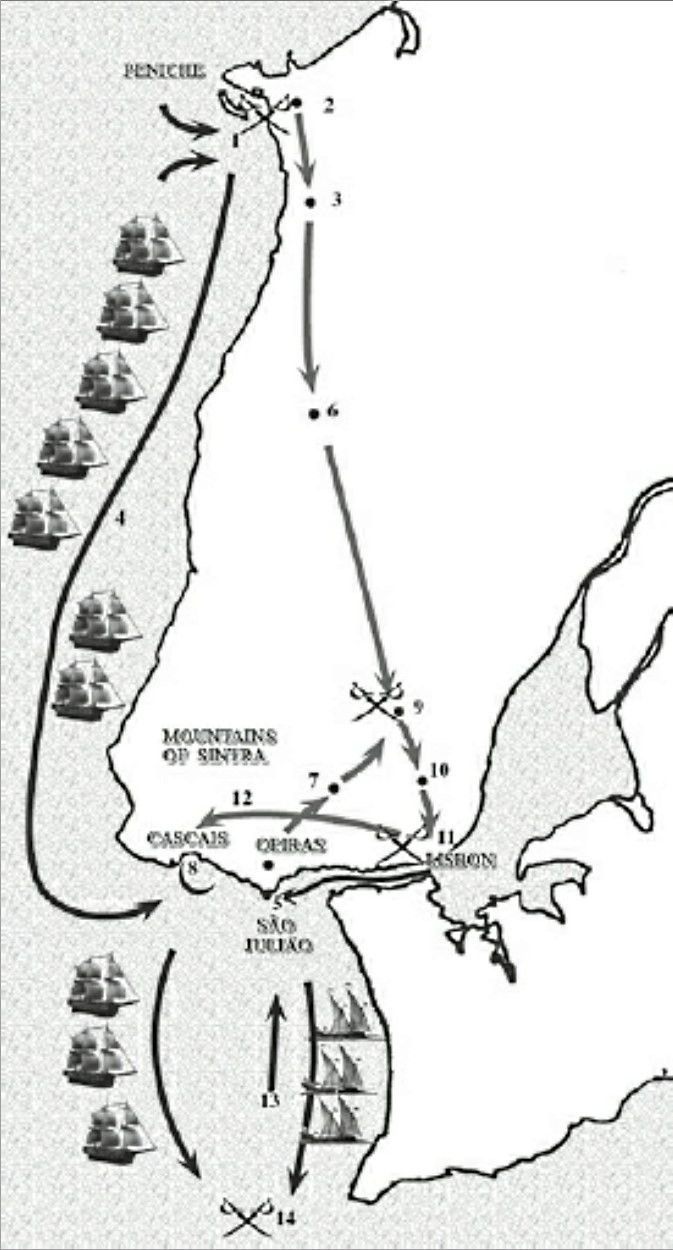

Map: 25 May–20 June, Lisbon.

1.25 May. A council of war held off Peniche where it

is decided to undertake an expedition on land, ruling out a naval attack on

Lisbon on 26 May. Difficult disembarkation on Consolaçao beach; of the

thirty-two landing craft, fourteen went under with over eighty men drowned.

First skirmish on the beach: two hours and three charges with 250 Spanish and

150 Portuguese under Captain Alarcón and Juan González de Ateide. Death of

Captains Robert Piew and Jackson plus other men. Death of a standard-bearer and

fifteen Spaniards. 12,000 soldiers are landed.

2.27 May. Contact with the Portuguese at Peniche and

Atouguia. Preparations for the march. Attack by the cavalry of Captain Gaspar

de Alarcón: five dead plus one French prisoner who speaks Spanish: he reports

that the English Armada is bringing 20,000 men. Surrender of the fortress to

Dom António.

3.28 May. The English army reaches Lourinha, where it

has proved impossible to raise a Spanish–Portuguese army. Start of the Spanish

tactics to cut off supplies and communications. The army begins to starve.

4.28 May. Drake sets sail from Peniche to Cascais with

the whole fleet and 3,200 men. A further five hundred, left as a garrison in

Peniche, will be killed or captured.

5.28 May. Movement of Spanish troops transported in

galleys from Lisbon to São Julião and Oeiras to strengthen the naval front.

6.29 May. The English army reaches Torres Vedras.

Nobles in the area take flight. Fear in Lisbon. Locals who live outside the

walls take refuge in the city.

7.30 May. Iberian military parade in Queluz, where the

new headquarters has been set up.

8.30 May. Drake drops anchor between Cascais and São

Julião, adopting a crescent shape.

9.30–31 May. The English enter Loures. Dom António

announces that he will enter Lisbon on 1 June, the feast of Corpus Christi, but

on the night of 31 May there is a surprise Spanish attack with more than two

hundred dead.

10.1 June. The English reach Alvalade. Arms are

distributed to the Portuguese infantry.

11.2–4 June. The English army reaches Lisbon. They are

bombarded from the Saint George castle. Billeting in Lisbon. On 3 June there is

a great attack of the besieged against the English barracks.

12.5 June. Night-time withdrawal by the army to

Cascais, pursued by Spanish detachments. More than five hundred dead.

13.15 June. Arrival of the Adelantado of Castile with

fifteen galleys and six fireships.

14.19–20 June. The English Armada sails on a westerly

wind, the galleys set off in pursuit and sink or capture nine ships, a tender

and a barge. The fleet is dispersed.

As dawn broke on Wednesday, 21 June 1589, it was clear that

the English Armada was still in sight of land. While the first detachment of

the fleet continued its slow voyage northwards, Drake was to spend that day

sailing into the light onshore wind and tacking off the coast before reaching

Cascais. For its part, the damaged Gregory, which was lost out at sea,

struggled to sail northwards, while Fenner, who was even more lost and who had

to endure a storm in the night, headed off to the islands of Madeira, which

were relatively close by. These names make up for the anonymity of many other

lost ships of which we know nothing further. Meanwhile, the fifteen caravels

that had been made ready in Lisbon to come to the aid of the Azores were unable

to set sail due to the calm seas and westerly winds. While all this was

happening at sea, with the Duke of Aveiro remaining on full alert on land, the

detachment of Guzmán and Bravo reached Torres Vedras, where they learned of the

situation at Peniche from Martinho Soares.

Westerly winds continued to blow on 22 June, and nothing of

significance changed at sea, although it did at Peniche. In fact, as Guzmán and

Bravo’s detachment reached Lourinhã on their way there, they received

a report from a spy at Peniche that the enemy were trying

to embark and take the artillery from the Tower. They all set off in haste

towards Peniche, where they discovered some of the enemy already embarked on a

small ship and a barge which were already in the water (and) about 40 of them

got on board, while of those still on land they killed or captured almost 300.

Although English sources do not appear to confirm that there

were any survivors apart from Captain Barton, there must have been some, for

‘although they were making haste, before they arrived they received news of the

embarkation, and so spurring on their horses as much as they could they arrived

with some two hundred yet to board and killed them or took them prisoner’.

About two hundred, therefore, remained on land, and they were killed or

captured together with others who were already on board. It is not known how

many others managed to escape, but if disease had not taken too great a toll in

the English garrison at Peniche, it could have been a sizeable number. What is

clear is that, given the great urgency to prevent the men from getting on

board, the only ones to arrive in time to prevent it were the cavalry. In any

event, the haste to embark was such that ‘a chest full of papers belonging to

Dom António was found, and amongst some important ones there was one written in

his own hand that described everything that had happened to him from the time

he had declared himself king to the day he arrived in this kingdom’. These

papers would help to thwart Dom António’s plans once and for all.

Following this bloody encounter, the Iberians reclaimed the

castle and its artillery. ‘In case any ships arrived, Pedro García’s company of

Maestre de Campo Francisco de Toledo’s regiment, remained in the castle.’ With

this new victory, ‘Don Pedro de Guzmán and Don Sancho Bravo, with their

infantry and cavalry, returned to Lisbon with about 60 prisoners.’ The failure

of the English expedition and the subsequent feeling of relief on the Iberian

side loomed larger by the day.

As he had on previous days, Drake continued to sail close to

the Portuguese coast during the morning of Friday, 23 June in order to make

progress northwards and that is how the English Armada found itself off the

coast at Peniche. He then sent in the rescue boats but, as fate would have it,

the men who had been looking for such a sign of deliverance from the

battlements of Peniche were no longer there. The ships – there were nine or ten

of them – were kept at bay from Peniche by cannon fire and they returned to the

fleet. Meanwhile, the English Armada was stretched out along the coast like the

net of a fishing trawler or the Santa Compaña that by night seizes anyone that

looks at it. Yet another merchant ship – a Hanseatic supply ship from Lübeck –

fell into their clutches that day. But the extraordinary thing was that its

captain was held on Drake’s Revenge until they reached Plymouth – perhaps

because it was a ship captured at sea and to prevent any attempt to escape.

Once he was back on the Peninsula, the captain, whose name was Juan Antonio

Bigbaque, wrote a very interesting account of what happened.

That day a north-east wind got up after all the calms and

westerlies and Drake set off for the open sea. That is when the fleet appeared

to head for the Azores; as Hume put it: ‘After sailing ostensibly for the

Azores, Drake turned back.’ But given the state of the fleet and the diverse

nature of its composition, to attempt such a voyage of conquest seemed like an

act of recklessness. Bigbaque, who witnessed the events, reported: ‘(Drake’s)

principal objective was to end up in the Cíes Islands, but because the weather

was so changeable from one day to the next, he decided to head for the island

of Madeira. He sent barges to inform all the ships of the fleet, but later when

the wind turned, he set course for Bayona and the Cíes Islands.’ With adverse

winds for the return to England, with the coast on a war footing and swarming

with galleys, with the great prize of merchant ships, and above all with the

state of the fleet worsening rapidly and making it increasingly necessary to

stop in order to recuperate, the Madeira Islands could be seen as an

appropriate place for a stopover after six perilous and pointless days at sea.

In any event, 23 June was the last day that the fleet was sighted from the

vicinity of Lisbon and Peniche.

With the English Armada out to sea, the Spanish were

suffering the same degree of uncertainty on Saturday, 24 June, as they had at

the beginning of May: not knowing where a new landing by the English might take

place. However, the situation was not the same, both on account of the drastic

reduction in the power of the English fleet and the arrival of Philip’s troops

in Portugal, including Juan del Águila’s infantry and Luis de Toledo’s cavalry.

Hence Fuentes ordered that

as an attempt could be made between the Douro and Minho

or in Galicia, it seemed advisable that the infantry and cavalry under Don Juan

del Águila and Don Luis de Toledo should be accommodated in Coimbra and the

surrounding area, for it is situated at the centre of the region and should the

need arise they can reach any part of the area.

The Count also ordered that ‘in order for the billeting to

be acceptable and convenient for the locals,’ everything should be done under

the supervision of the Count of Portoalegre, and ‘they should be given

excellent treatment there’.

On the same day, Fuentes sent two more caravels with men and

supplies to reinforce the two that were tailing the English Armada. In

addition, he began the recruitment of sailors for the new Armada that was being

prepared for the following year. For his part, Alonso de Bazán, who had been

called upon by the King for this new Armada, wrote to him on that day to say

that with the invaders now definitely gone from Lisbon, he would travel to the

Court immediately.

As for the English, it was on the Saturday that Robert

Devereux, Earl of Essex, more or less unwittingly rendered one last service to

the expedition by providing Cerralbo with the same major headaches as he had

suffered in May and in the process making the Vigo estuary more vulnerable. In

fact, the first sighting of the first squadron of the English Armada occurred

on that day in the Rías Altas, off the Costa de la Muerte. It included the

favourite Devereux with many other nobles, a good number of English ships

carrying the sick and the discharged Dutch vessels. This sighting created a

counterproductive movement of Galician troops, for when Cerralbo thought that

the English Armada was going to attack Corunna again, he ordered the three

companies that were stationed in Pontevedra as reinforcements for Vigo and the

Rías Bajas to return at once to Corunna. It would have been far better in this

game of cat and mouse for these veteran soldiers to have remained in

Pontevedra, for this would have spared them gruelling and futile marches across

the Galician countryside that took them away from the place where the final

attack by the English Armada would be unleashed shortly afterwards.

On Sunday, 25 June, the northerly winds and rough weather

intensified. As night fell, Drake, who had sailed out to sea on 23 June, was

sighted off Oporto. These facts suggest that Drake took advantage of the

north-easterly wind on 23 June, sailed west-northwest at the start of what was

to be a long tacking movement (that led some to think that he was heading for

the Azores). At some point on 24 June, now at some distance from the coast and

with the wind from the north, the tacking took them several miles out to sea.

Following the change in direction and sailing into the wind as much as possible

in order to get as far north as he could, he started a new tack, this time back

towards the Portuguese coast. Finally, on 25 June, with the ships leaning hard

to starboard, he completed the tack which took him to within five miles of

Oporto. As far as the first squadron of the English Armada was concerned, it

tacked using the northerly wind to reach Finisterre, while trying not to lose

too much of the northern advance already made.

The northerly wind was still blowing on Monday, 26 June, and

Drake was tacking gently off the north coast of Portugal between Vila do Conde

and Esposende under the watchful eye of Pedro Bermúdez, commander of the

military garrison in that sector. The first squadron of the fleet was doing the

same off the Galician coast and was seen again that day from Finisterre. On the

Spanish side, that was the day that the fifteen caravels at last set sail to

reinforce the Azores. Meanwhile, the Gregory from London which, as mentioned

earlier, had been hit by the guns from the galleys days before, ‘was not

sailing as well as the rest’ and had got detached from the fleet, managed to

join up with them again. According to Evesham’s account that was also the night

when, in addition to the gradual dispersal of individual ships, the second

squadron of the English Armada was in turn split in two. Evesham described how

during the night Drake lit a beacon on the Revenge, which by daybreak had

disappeared along with sixty ships.

On Tuesday, 27 June, the wind continued to blow, resulting

in the virtual standstill of the English ships, which were becoming more and

more spread out as they tried to sail into the wind off the Portuguese and

Galician coasts. Tragically, they were being held back, with the vessels

beginning to look more like mortuaries owing to the relentless increase in

hunger, thirst, sickness and death.

By 28 June, most of the second squadron of the English

Armada was close to the Portuguese–Galician border between Viana and Caminha.

In fact, a number of ships showed signs of attempting to land on Ancora beach

next to the river. But the same day the wind veered to the south, and so they

were able to sail towards the estuaries which offered unparalleled respite for

any ship exhausted from being at sea. However, they did not all anchor in Vigo

as a number of them headed straight off to England. One of these was the

Gregory, which headed north after abandoning a lost supply ship that it had

come across and which decided to stay. Shortly afterwards, the Gregory came

across another ship on its own, the Bark Bonner from Plymouth, and they decided

to keep each other company on the tough voyage that awaited them on their

homeward journey.

But on 29 June Drake finally managed to drop anchor off Vigo

and, throughout that day, a large number of ships came to join him there. In

conclusion, Drake had the wind in his favour to head for the Azores and against

him to return to England. But what he wanted was to go home and, from setting

sail from Cascais on 18 June until a southerly wind got up on 28 June, he had

tacked against the wind in order to make some headway north. And during that

time, disease and hunger began to seriously ravage the fleet.