König Wilhelm was also designed for ramming. Between 1862 and 1893 more warships were sunk or heavily damaged by accidental ramming than were sunk in battle.

Lissa naval battle, July 20th,1866; the Austrian navy

against the Italian fleet. The RN Re d’Italia is sinking after being rammed by

Tegetthoff’s flagship, the SMS Ferdinand Max.

The next ironclad battle occurred in 1866, when the fleets

of Austria and Italy met off the island of Lissa in the Adriatic. This time

there was real meat for analysis, or so it appeared, for the first-line vessels

of both powers were sea-going warships in direct descent from the Gloire, some

of the most recent construction. More important perhaps, it was the only fleet

action which took place until the end of the century, so it had to be picked

bare.

The conflict was an offshoot of Bismarck’s grand policy for

removing diverse north German states from Austria’s orbit and uniting them

under Prussian leadership. He arranged a war with Austria, first tempting Italy

into an alliance with the prospect of Austrian Venetia and Lombardy,

territories they needed to complete their unification. But, while Bismarck’s

army quickly defeated the Austrians at Sadowa, the Italians were beaten at

Custozza; this was particularly embarrassing for the new nation, and weakened

their position in any peace negotiations which Bismarck might achieve. They

turned to their fleet. On paper it was superb. Since unification they had spent

some £12 millions on it, millions they could ill afford, and materially it was

far superior to the Austrian Navy which had been neglected since the initial

burst into ironclad construction. However, the Italians’ ships and armament had

come from different countries and they had no pool of marine engineers or

modern gunners; nor, it seems, a tradition of naval discipline. The new force

was a young and artificial creation, and the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Count

Persano, seems to have been overwhelmed by the practical difficulties of the

situation. He did little training and, when the war started, nothing offensive.

The Minister of Marine tried to sting him to action. ‘Would

you tell the people who in their mad vanity believe their sailors the best in

the world, that in spite of the £12 millions we have added to their debt, the

squadron we have collected is one incapable of facing the enemy?’3 When Persano

still showed reluctance, he was ordered to take the Austrian-held and fortified

island of Lissa, across the Adriatic from Ancona. His attempts to do so were

reported to the Austrian Commander-in-Chief, Rear Admiral Tegetthoff, who put

to sea to fight him.

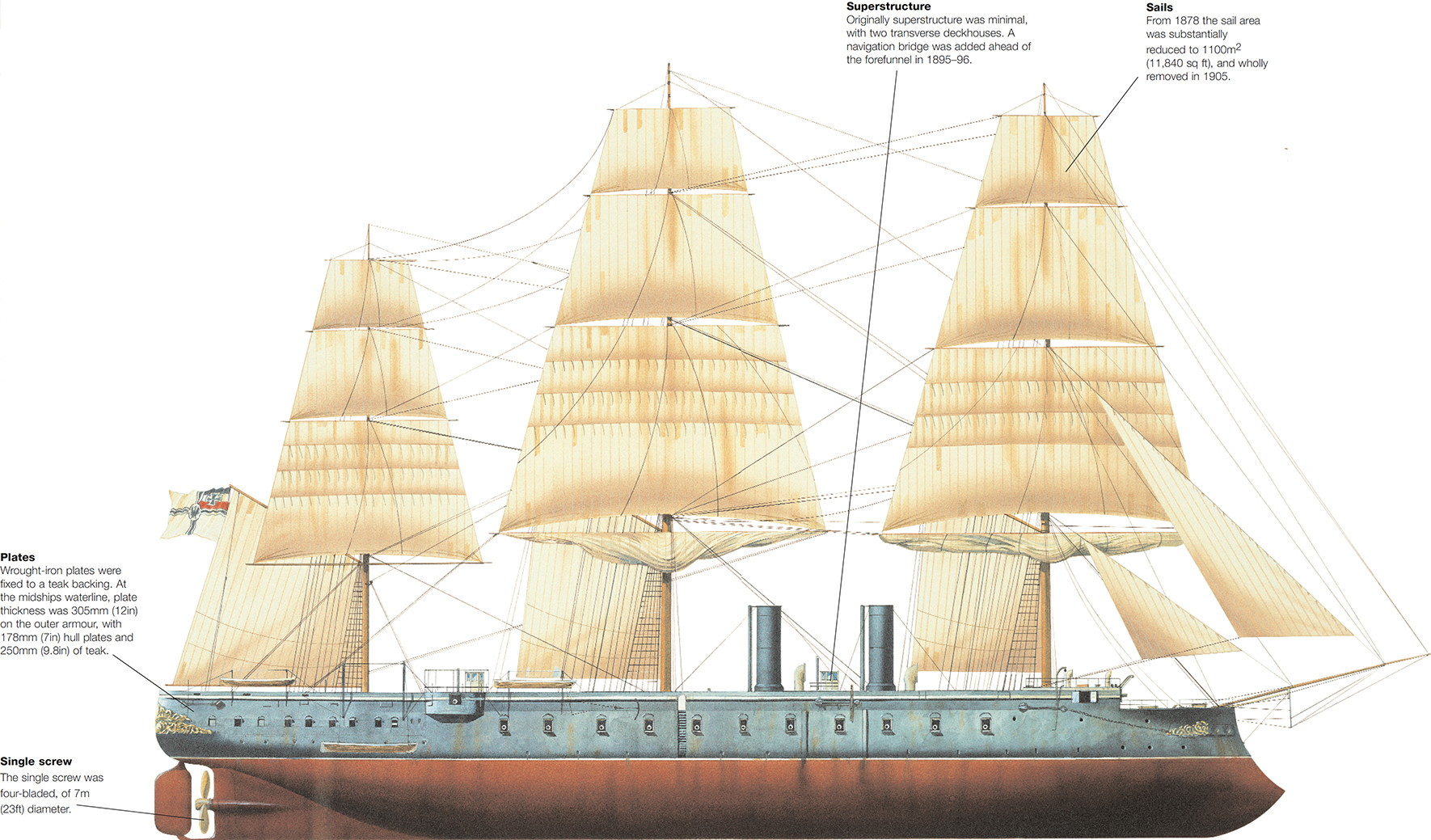

Tegetthoff flew his flag in the Ferdinand Max; she was a

barque-rigged 5,140 ton vessel on the lines of the Gloire launched the previous

year with complete armour plating reaching a maximum thickness of 5-inches on

26-inches of timber backing. However, while she had been designed for a

powerful battery of Krupp rifles on each broadside, the Prussian firm had been

backward in supply and instead she had been fitted with 16 obsolescent

smooth-bores throwing 56lb projectiles. She and a sister ship, Habsburg, which

suffered the same disadvantage, were the spearhead of the fleet. In addition

there were four smaller ironclad frigates of 3,000–3,600 tons which mounted in

total 74 62-pounder rifles together with 66 smooth-bores. There were also

numerous timber vessels including a ship-of-the-line, Kaiser.

The Italian fleet was more imposing. The flagship Re

d’Italia and her sister Re di Portogallo were 5,700 tons, rather larger than

the Austrian big ships and with rather thicker armour, although built to the

same style. But their main theoretical advantage lay in their batteries; the

flagship mounted 30 Armstrong 100-pounder rifles and two rifles throwing 150lb

shells, while her sister ship had 26 of the 100-pounders and two throwing 300lb

shells. In addition there were five ironclad frigates just over 4,000 tons

mounting a total of 108 rifles and a few smooth bores, two smaller armoured

vessels and a number of timber craft. Altogether the principal units in the

Italian fleet were larger than their Austrian opposite numbers and mounted 200

modern rifled guns against only 74 smaller Austrian pieces.

The Italians also had a curious 4,000 ton vessel known as a

turret ram, the Affondatore. Her design was probably due to the successful

rammings of the American Civil War for she had a de Bergerac of a beak

extending 26 feet; she also had a turret mounting two powerful Armstrong

300-pounder rifles, hence her designation, and she was armoured with 5-inch

iron plate. The Italians expected great things from her.

So much for matériel comparisons: what was thought more

important when the naval post mortems came to be written was the comparison

between the querulous Count Persano and Tegetthoff, who ordered his mind and

his fleet in a more positive way, exercised his ships and guns frequently, and

was in all respects an inspiring leader.

He was certainly an agressive one. On the morning of 20

July, having sighted the Italian fleet, he formed his ships into three

divisions behind one another each in double quarterline, like three arrowheads,

with the ironclads leading, and charged at full fleet speed—something like 9

knots. His intention was to go through the Italian line and provoke a mêlée,

partly because he knew the Italian rifles had the greater effective range and

he needed to get in close, where the ‘concentration’ fire in which he had

trained his gunners might tell, but primarily to ram, since his shells could

not pierce the Italian armour. As the Ferdinand Max neared the grey-painted

Italian vessels he signalled. ‘Charge the enemy and sink him’.

Persano, who had collected his fleet together from various

positions around the island, intended to fight a line battle and make use of

his heavier guns; he was not averse to ramming but he meant to disable some

enemy ships with broadsides first and ordered his captains to engage unarmoured

ships at 1,000 metres, armoured ships not outside 500 metres. Then he formed up

with his ironclads in three divisions in line ahead, steaming north-north-east

to meet the Austrians coming down south-east, placing his flagship in the

centre division and his turret ram just to starboard, thus on the disengaged

side of the centre division. His unarmoured ships were ordered to the

disengaged side, distant 3,000 metres. So far his tactics appear sound. But

then he decided to shift his flag from the Re d’Italia to the turret ram

Affondatore; this meant stopping the ships concerned and a gap opened up

between the first division of three frigates, and the rest of the line.

Meanwhile the first division, disregarding orders, opened fire at Tegetthoff’s

approaching ironclads, which were still about 1,000 metres off. The great

clouds of smoke from their broadsides drifted astern, concealing the widening

gap which Persano had created by his eccentric behaviour, and it was through

this gap and smoke that Tegetthoff’s whole ironclad division, holding its fire,

soon passed.

Once they were through the line Tegetthoff’s seven ironclads

formed into two groups, one of which turned north to chase the Italian van

(itself turning in to attack the Austrian unarmoured rear) while the main body

of four frigates fell on the Italian centre. Meanwhile the second Austrian V

formation of timber ships headed by the line-of-battle ship Kaiser, reached the

Italian rear and, attempting to run down whatever they could see, provoked a

mêlée which quickly became shrouded in dense gunsmoke. The situation was now

exactly as Tegetthoff had hoped, a close, confused scramble, all central

control lost and with it any possibility of cool, stand-off gunnery.

Opportunism ruled the day.

It is impossible to follow all the contortions the ships

were put through; the main object on both sides was to ram any enemy as they

made him out, and while they held on with tight nerves for their target, often

charging towards them for the same purpose, the guns’ crews waited for the

shock and the chance to get in a broadside as they came together or raced past

The collsions, near misses, touchings and scrapings, many between friends

unable to get out of the way in time, were numerous, but at first none were

fatal. Even the Affondatore failed to bring her prow into contact with such a

ripe target as the Kaiser in two attempts, although she wrought fearful damage

in the timber upperworks with 300-pounder shells at pistol-shot range. The

Kaiser for her part, passed on from this desperate affair to try and ram the

large frigate Re di Portogallo, which was steaming at her with the same intent,

and spinning her wheel over at the last moment made contact abreast the

Italian’s engine room, but at far too fine an angle to enter. Instead she

scraped down the iron side, losing her bowsprit and taking a broadside of

shells which brought down her foremast, turned her gun decks into shambles and

started numerous fires. The Maria Pia, astern of the Portogallo, put two more

shells into her as she came past and she retired to put out fires and

reorganize the fighting decks.

Meanwhile, around what had been the Italian centre,

Tegetthoff, who had been no more successful in ramming than Persano, saw

through the fog of battle the Re d’ltalia apparently disabled; he made straight

for her, his flag captain conning from the mizzen rigging. The Italian’s rudder

had been damaged by collision or a lucky shell and she couldn’t turn her side

as the Ferdinand Max’s stem approached at full speed, something over 10 knots,

and drove straight in, tearing a gap of about 140 square feet, half below

water. The Austrian flagship reversed engines and withdrew; the Re d’Italia

listed slowly to starboard, suddenly lost stability, rolled to port and went

down. Meanwhile a small Italian gunboat, Palestro, dashing in heroically to aid

the ironclad, received a shell in her wardroom which set it alight and forced

her to retire; later she blew up as the flames reached the magazine.

These were the only ship losses of the battle. For the rest,

the astonishing series of abortive charges, scrapes and accidental collisions

punctuated by broadsides at point-blank swinging targets continued until early

afternoon. Then Persano led his scarred ships back to Ancona, while Teggethoff

anchored his off Lissa, evidently the victor in possession of the field.

This battle again confirmed the value of armour as

protection for ships and guns’ crews. The Austrian ironclads fired 1,386 shot

or shell, the three largest of their unarmoured ships fired another 1,400, and

the rest of their fleet joined in as well, but the total Italian casualties,

apart from those drowned in the Re d’Italia and blown up in the Palestro, were

eight killed, 40 wounded. The Italian fleet fired at least 1,400 shells,

probably many more, but the total Austrian casualties in their armoured

division were three killed, 30 wounded; the unprotected Kaiser meanwhile lost

24 killed, 75 wounded. Armour was not the only reason for such comparatively

low casualties: another was the small proportion of hits, and even smaller

proportion of hulling hits. For instance the Austrian flagship received a total

of 42 hits, but only eight were against her armour, the rest were above. This

was not unusual in fights between rolling ships, particularly with

indifferently trained gunners, but in this case it was exaggerated by the

twisting, turning, listing, passing nature of the fight, which although close,

forced gun captains to fire the instant they saw a target briefly through the

ports. Effective hulling gunnery required steady ships and steady courses.

However, hits on thick armour failed to pierce even from the closest range.

But the main lesson drawn from the battle was the power of

the ram. The dramatic picture of the Re d’ltalia disappearing at one blow,

while so much gunnery had hardly accomplished anything, drove out all power of

rational analysis. The facts, clear enough in all reports, were that ramming,

tried and accidentally achieved scores of times by dozens of ships in ideal

conditions, had failed every time it had been attempted against a ship under

command; the single success had been against a ship unable to steer. Individual

reports showed how a ship about to be rammed could, by a sudden turn of the

helm, herself become the rammer, though at too sharp an angle to be decisive.

However, it must be remembered that steam was still in its

infancy at sea, and naval officers, sail-trained and sail-thinking, while

professing to despise engines, held them in some awe. Besides there was already

a strong school, apparently logical and of French origin, in favour of ramming.

The argument was: engines gave free movement, thus the ability to close and bring

the whole gigantic momentum of the ship against the enemy at his most

vulnerable point below the waterline, below armour. And compared with the

energy of a ship in motion even the largest gun was little better than a

pea-shooter. Such a logical approach took little account of an enemy’s evasive

tactics. Practical experiment with models or small steam boats might have put

it into perspective and explained the extraordinary inefficiency of the ram in

its own conditions at Lissa. This is clear from hindsight and in the light of

modern theory; what was clear in 1866 was that the ram had proved itself in

battle, and this led naval constructors and most naval tacticians up false

trails for decades.

On the other hand armour was undoubtedly master over the gun

at the time, and at first it was not evident that the situation was going to

change; so while the ram was overestimated, it was a reasonable addition to the

armament of a warship at the time. The mistake designers and tacticians made

was to treat it as almost the prime feature of a ship, bending other features

such as the arrangement of guns, or fleets, to suit.

The other two lessons extracted from the battle were that

morale counted for more than material force, and that line ahead was a bad

formation for steam warships. Like the conclusion on the ram, both these were

already well established ideas among those who liked to theorize about naval

warfare, and Teggetthoff’s victory gave them practical respectability.

Probably the real conclusion to be drawn about the tactics

of Lissa is that they were transitional. They belonged to a brief period during

which the armourclad ship was impregnable to the great gun, and they appear to

parallel the early days of the gunned sailing ship when the stout timbers of an

Atlantic galleon could resist the heavy guns of the time and contests had to be

decided by boarding and entering. All the principles of the massed charge and

the attempts to clap vessels together distinguished that period too. And it was

only as the great gun became sufficiently powerful to decide an action without

recourse to boarding that tactics changed, and ships changed to take account of

them.

As for Persano’s line tactics, they were not pursued with

determination, indeed they were thrown away. There can be few more

extraordinary lapses in fleet command than his self-provoked break in formation

in the face of an enemy under a mile away and bearing down upon him. As a

result it is not possible to say whether a steady, compact line holding its

fire until Teggetthoff had closed to 500 metres would have been successful in

preventing a mêlée at the opening; the chances are that effective range was too

low, ironclads too invulnerable and the guns too slow in loading and firing for

such a cool order to have disorganized a resolute enemy like Teggetthoff.