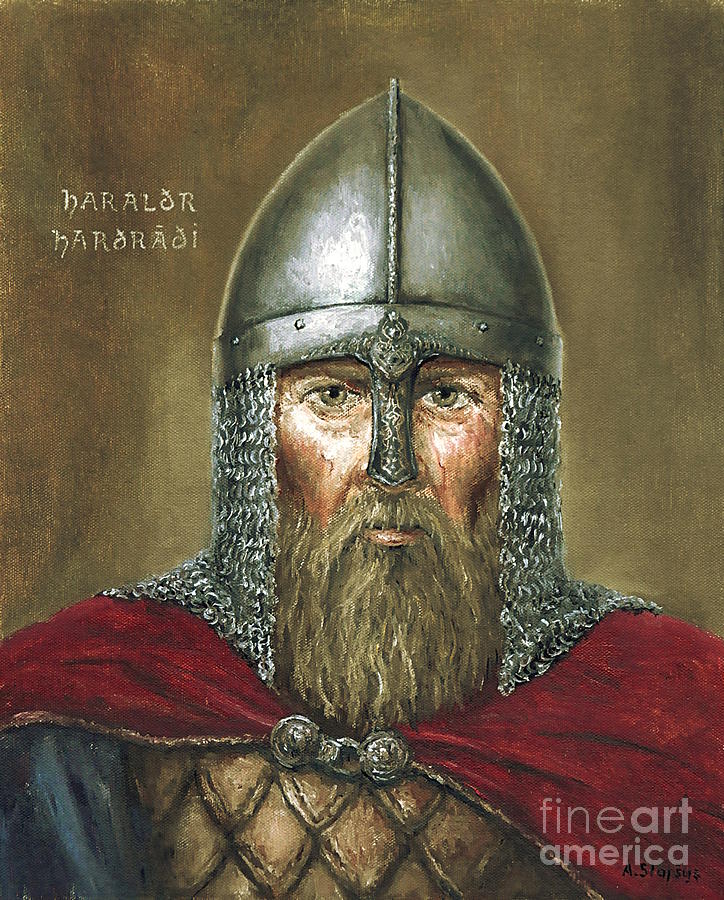

Contemporaries, it is clear, stood in awe of Harold Sigurdson [note] [Harald Sigurdsson]. ‘The thunderbolt of the North’, was how Adam of Bremen, who wrote in the 1070s, remembered him; ‘the strongest living man under the sun’, said William of Poitiers (albeit reporting the words of somebody else). A half-brother of King Olaf II of Norway, born around 1015, Harold had been forced to flee from his native country while still in his teens, and ended up spending several years at the court of Yaroslav the Wise, king of Russia. From there he ventured south, like countless generations of Vikings before him, to Constantinople, capital of Byzantium, the eastern rump of the Roman Empire, and rose to great power and eminence by rendering military service to successive emperors. His reputation and his fortune won, he returned to Scandinavia in the mid-1040s and used his well-honed skills to make himself king of Norway, where he subsequently reigned with a fist of iron, fighting his neighbours and executing his rivals. Small wonder that when later Norse historians looked back on his life they dubbed him ‘the Hard Ruler’, or Hardrada.

The fact that his famous nickname was not recorded until the

thirteenth century, however, alerts us immediately to an inescapable problem.

Harold’s contemporaries may have been impressed by his epic tale, but they did

not write it down – unsurprisingly, for eleventh-century Scandinavia was still

for the most part a pagan society and hence largely illiterate. The first

sources to deal with his reign in any detail are Norse sagas dating from the

late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, almost 150 years after the events

they purport to describe. The most celebrated account of all – the so-called

King Harold’s Saga – was told by an Icelandic historian called Snorri

Sturluson, who died in 1241 and wrote in the 1220s and 1230s – that is, almost

two centuries after Harold’s own time.

How much trust can we place in such late sources? On the

positive side, we can see from similarities in his text that Snorri drew on

earlier sagas, as well as oral traditions. He also considered himself to be an

objective writer, and in several passages seeks to reassure his readers of his

conscientiousness as a historian. Halfway through King Harold’s Saga, for

example, he explains that he has omitted many of the feats ascribed to his

protagonist, ‘partly because of my lack of knowledge, and partly because I am

reluctant to place on record stories that are unsubstantiated. Although I have

been told various stories and have heard about other deeds, it seems to me

better that my account should later be expanded than that it should have to be

emended.’

There is no reason to doubt Snorri’s sincerity but, alas, we

cannot set as much store by his stories as we could with a contemporary source,

especially when it comes to points of detail. Take, for instance, his account

of Harold’s adventures in the east. On the one hand, we can be absolutely

certain that the future king went to Constantinople, and that he rose to a

position of prominence there, because he appears in contemporary Byzantine

sources (as ‘Araltes’). These same sources confirm Snorri’s statements that

Harold fought for the emperor in Sicily and Bulgaria, and show that he

ultimately obtained the rank of spatharocandidate, just three levels below the

emperor himself. But, on the other hand, when it comes to the details of

Harold’s eastern adventures, the same local sources show that Snorri was often

wrong. Sometimes he gives events in the incorrect order, and at other times he

gets the names of key individuals confused. Harold, for instance, is said by

Snorri to have blinded Emperor Monomachus, whereas contemporary sources show

that the true victim was the previous emperor, Michael Calaphates. This leads

us to a general conclusion about the value of Snorri’s work. The broad thrust

of his story may well be true, but on points of detail it has to be regarded as

very suspect, and all but useless unless it can be corroborated by other, more

reliable witnesses.

Harold apparently returned from his adventures in the east

in 1045, at which point he intruded himself in the struggle for power in

Scandinavia between his nephew, King Magnus of Norway, and the king of Denmark,

Swein Estrithson. If there is any truth in Snorri’s version of events, the

former spatharocandidate employed the same underhand and unscrupulous methods

that had worked so effectively in Byzantium, siding first with Swein, but then

defecting to Magnus in return for a half-share of the latter’s kingdom. When

Magnus died in 1047 he reportedly bequeathed all of Norway to Harold and

declared that Swein should be left unmolested in possession of Denmark. His

uncle, however, was not the kind of man to settle for such half-measures, and

soon the war between the two countries was resumed.

According to some modern historians, Hardrada from the start

of his reign also had similar designs on England. There is, however, precious

little evidence to support such a view, either in the contemporary record or,

for that matter, in the later sagas. It is often said that the new Norwegian

king considered himself to have a claim to the English throne on account of the

alleged deal between Magnus and Harthacnut that each should be the other’s

heir. Whether this deal, first reported by a mid-twelfth-century writer, had

any basis in fact or not, Magnus certainly behaved as if England was his by

right. As we have seen, Edward the Confessor took the threat from Norway very

seriously during the early years of his reign, setting out every summer with

his fleet to defend his coast from invasion.

In the case of Harold Hardrada, by contrast, there is scant

evidence to indicate a similarly hostile intent. Historians have made much of

an obscure Norwegian raid that took place somewhere in England in 1058, led by

Hardrada’s son, Magnus, because an Irish annalist described it as an attempt at

conquest. In reality it can have been little more than a young man’s luckless

quest for adventure and booty. It finds no mention in any of the Norse sagas,

and was barely noticed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (‘A pirate host came from

Norway’, says the D version, briefly and uniquely, as a coda to its description

of Earl Ælfgar’s rebellion that year). Beyond this there is nothing in our

English sources to suggest that an invasion from Norway was either anticipated

or feared. Edward the Confessor, far from sailing out from Sandwich each

summer, disbanded his fleet in the early 1050s and cancelled the geld which

paid for it. Later in the reign, when the Godwine brothers were effectively

running the kingdom, neither demonstrated any concern with Scandinavian attack.

Tostig concentrated on securing peace with Scotland, and Harold on carrying war

into Wales, and both felt sufficiently confident to leave England for trips to

the Continent. Of course, one could argue that, by dealing with their Celtic

neighbours, the Godwines were strengthening the kingdom generally, and hence

improving its ability to withstand any future Viking assault, but that would

seem to be a fairly roundabout way to prepare were such an assault really

regarded as imminent. The reasonable conclusion is that it was not regarded as

such. Prior to 1066, Harold Hardrada is mentioned only once in the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle – at the start of his reign, when he sent messengers to England in

order to make peace.

The truth is that, from the moment of his accession onwards,

the Norwegian king was entirely preoccupied with his struggle against Swein

Estrithson for control of Denmark; not until 1064 did he agree to a permanent

peace, and even after that he had to contend with opposition within Norway

because of his oppressive rule. Both the Scandinavian and English sources, in

short, point to the same conclusion, which is that the idea of invading England

was not seriously entertained by Harold Hardrada until the year 1066 itself.

And the reason it took root that year, most likely, was because it was planted

by Tostig Godwineson.

Tostig, as we’ve already seen, had not responded well to the

prospect of a life in permanent exile. We know that after his banishment from

England in November 1065 he had fled to Flanders, and most likely it was from

Flanders that he returned in the spring of 1066, raiding along the southern and

eastern coasts before eventually retiring to Scotland. According to the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, he remained in Scotland as the guest of King Malcolm for

the rest of the summer.

Precisely how and when he established contact with Harold

Hardrada is therefore something of a mystery. One possibility is that he did so

early in the year, ahead of his spring raid. Such was the belief of Snorri

Sturluson, and it finds some support in other sources. A twelfth-century English

chronicler called Geoffrey Gaimar, for example, informs us that most of

Tostig’s own troops in the spring had been drawn from Flanders, but also says

that some ships had joined him from Orkney, a territory then under Norwegian

control. This has led some historians to see Tostig as the mastermind of an

elaborate strategy in 1066. In this view, his initial raid was not a failure at

all, but rather a clever diversionary tactic, a preliminary feint intended to

focus English attention on the south coast, away from the larger assault he was

planning to launch from the north. While this is possible, it does smack

somewhat of reading events backwards, and ascribing to Tostig’s cunning a

course of events that could easily have been determined by contingency. An

alternative reading is that the earl simply secured some sort of tacit

co-operation from Hardrada ahead of his spring attack, then, when that attack

failed, turned to him again in search of more substantial support.

Whenever it was that the two of them agreed to collaborate,

it seems very likely that in order to broker the alliance Tostig travelled to

Norway to meet Hardrada in person. Partly this is because it is hard to

conceive of such an alliance being struck without a personal meeting, but

mainly it is because Tostig’s arrival in Norway forms such a central plank of

the story as told in the Norse sagas. In Snorri’s account, and also in the

accounts of his known sources, Tostig first visits Denmark to seek the help of

King Swein, but his proposal is rejected. Disgruntled but undeterred, he pushes

on to Norway where he meets Hardrada at Oslo Fjord (appropriately, since the

city of Oslo was Hardrada’s own foundation). The Norwegian king is at first

aloof and suspicious, telling Tostig that his subjects will not be keen to

participate. Tostig, however, proceeds to talk Hardrada around, reminding the

king of his putative claim, and plying him with compliments (‘Everyone knows

that there has never been a warrior in Scandinavia to compare with you’). He also

stresses that the conquest of England will be easy on account of his own

involvement, telling the king: ‘I can ensure that the majority of the magnates

there will be your friends.’ Of course, we do not have to accept any of the

specifics here – Snorri is dramatizing, and the speeches must be made up. Yet,

for all the invented detail, one suspects that the essence of his account is

true. Hardrada had built a career on opportunism and violence; the prospect of

one last great adventure, of replicating the success of King Cnut, or simply of

recapturing the flavour of his glory days in the Mediterranean, must have been

extremely enticing. Moreover, the expectation of support from within England

itself would have made the enterprise seem feasible. The Scandinavian tradition

that Tostig’s visit to Norway set Hardrada’s invasion in motion is, in short,

very hard to dismiss. Nor is it unsupported by earlier sources: Orderic

Vitalis, writing in the early twelfth century, says much the same thing,

explaining that the earl’s proposal greatly pleased the covetous Norwegian

king. ‘At once he ordered an army to be gathered together, weapons of war

prepared, and the royal fleet fitted out.’

If Tostig went to Norway from Scotland, he was clearly back

in Scotland by the end of the summer: when Hardrada set sail towards the end of

August, his English ally was not with him. The king was accompanied, however,

by several members of his own family, including his queen, Elizabeth, two of

his daughters and one of his younger sons. His eldest son, Magnus, he left

behind in Norway to act as regent, having first taken the precaution of naming

him as his heir in the event of his non-return. As to the size of his fleet, we

have a predictable variety of estimates. The contemporary Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

suggests it contained 300 ships, while John of Worcester later increased the

figure to 500. Snorri, from whom we might expect even greater exaggeration,

says that Hardrada assembled a great host, reported to have contained more than

200 ships, plus smaller craft for carrying supplies: a useful reminder that

even a fleet of this size constituted an enormous deployment, and a caution

against believing the far larger numbers offered by other chroniclers for

fleets in this period. If each of the Norwegian king’s 200 ships carried a

modest average of forty passengers apiece, this would still have given him an

army of 8,000 men.

Snorri says quite credibly that Hardrada sailed first to

Shetland and then to Orkney, where he was joined by the local earls and where

he left behind his wife and daughters. From the Northern Isles he proceeded

down the east coasts of Scotland and Northumbria until he reached the River

Tyne, where (according to the most detailed English sources) he met up again

with Tostig. Whether the earl had managed to add to the meagre flotilla of

twelve ships that had limped to Scotland with him at the start of the summer is

unknown; but even if King Malcolm had increased the naval resources of his

sometime sworn brother, it would have been apparent to all that Tostig was very

much the junior partner. Hardrada had come in great force to conquer England

and make himself its new ruler. On his arrival, says the Chronicle, the earl

swore allegiance to him as his new sovereign. Together they then set out on the

last leg of the voyage, sailing and raiding along England’s north-eastern coast

(Snorri, for what it’s worth, describes significant encounters at Scarborough

and Holderness), before eventually turning up in the estuary of the Humber, and

then making their way up the River Ouse. Eventually they landed at Riccall, a

settlement on the Ouse’s north bank, some ten miles south of their principal

target: the city of York.

Although they cannot have planned it with any great

precision, the invaders had apparently timed their arrival to perfection. We

have no certain dates for their progress around the Northumbrian coast, but the

testimony of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests it occurred in the first week

of September. Any earlier and news of their coming would have reached southern

England before 8 September – the day on which, according to the Chronicle,

Harold Godwineson dismissed the great army and fleet he had held in readiness

since the start of the summer. At the same time, the Norwegian invasion can

hardly have begun any later in September, because the Chronicle also says that

Harold received the terrible news as soon as he reached London, presumably just

a few days after he had left the Isle of Wight. The inescapable conclusion –

and how utterly galling it must have been for the English king – is that he

must have disbanded his army at more or less exactly the moment that the

invaders had disembarked.

This dramatic turn of events, more than anything else, shows

how totally unexpected an attack from the north had been. Harold had spent the

whole summer preparing for an assault from Normandy; all his resources were

directed southwards. This alone suggests that the notion, advanced in many

modern history books, that a Scandinavian invasion of England had been long

anticipated is simply an assumption, without any evidence to recommend it. All

the evidence, both direct and circumstantial, actually points in the opposite

direction, and indicates that the invaders had kept their intentions well concealed.

Orderic Vitalis, for example, claims that nothing had been known in Normandy

about Hardrada’s preparations, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that the

Norwegian fleet had arrived in England ‘unwaran’ – unexpectedly.

It was obviously imperative that Harold speedily reassemble

his forces. The fleet which he had sent back to London was apparently still

intact, although according to the Chronicle many ships had been lost as they

had made their way around the south coast, presumably due to bad weather in the

Channel. The king would also still have had with him his housecarls, ready as

ever to form the nucleus of any new army. But he had no time to wait while such

an army regrouped in London. Harold can have paused in the city for only a few

days before setting out for Yorkshire and, as he did so, messengers must have

ridden in all directions, recalling the thegns who had been dismissed only days

beforehand. The English king, says the Chronicle, ‘marched northwards day and

night, as quickly as he could assemble his levies’.

What had been happening in Yorkshire during the second week

of September is altogether unclear. Hardrada and Tostig had made their camp at

Riccall, and must have sent their troops out into the surrounding countryside

to plunder it for provisions; as yet, however, there had apparently been no

assault on York. All we know for certain is that during this period the earls

of Mercia and Northumbria, Eadwine and Morcar, began raising an army of their

own with which to confront the invaders, and that by the third week of

September they obviously felt sufficiently confident in their numbers to risk

an engagement. On 20 September the two sides met just to the south of York, on

the east side of the Ouse, at a place called Fulford.

Sadly, despite modern attempts to reconstruct this battle,

the truth is that we can say next to nothing about it. Even its location was

not recorded until the twelfth century, and Snorri’s account is so demonstrably

inaccurate as to be virtually worthless. He does provide the colourful detail

that Hardrada advanced behind his famous banner, ‘Land-waster’, which earlier

in the saga is said to have had the magical property of guaranteeing victory to

its bearer. It evidently worked its magic that day at Fulford, for the only

certain fact about the battle is that Eadwine and Morcar were defeated. The C

version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, compiled at a Mercian monastery, tried

its best to preserve the honour of its patrons, reporting that they inflicted

heavy casualties on the invaders, but could not disguise the final outcome. ‘A

great number of the English were slain or drowned or driven in flight,’ it

lamented, ‘and the Norwegians had possession of the place of slaughter.’

Eadwine and Morcar themselves must have been among the fugitives, for (despite

Snorri’s assertions to the contrary) both brothers survived the battle.

In the wake of their victory, the Norwegians entered York.

We might imagine that the city would have been put to the sack, but this was

clearly not the case. ‘After the battle,’ says the C Chronicle, ‘King Harold of

Norway and Earl Tostig went into York with as large a force as suited them, and

they were given hostages from the city as well as provisions.’ This sounds very

much as if the citizens of York had surrendered without a fight and obtained

good terms. John of Worcester, when he later rewrote this section of the

Chronicle, actually stated that there was an exchange of hostages between the

two sides, with 150 townspeople being swapped for an identical number of

Norwegians. Here indeed was the friendly collaboration that Hardrada had been

led to expect. Tostig may have been the target of Northumbrian hostility the

previous year, but he could evidently call upon the support of at least some

sections of society in Yorkshire – especially now he had a victorious Viking

army at his back. The Anglo-Danish aristocracy of York had always worn its

loyalty to the south lightly; faced with the choice between a new Scandinavian

ruler or a recently crowned earl of Wessex, they readily chose the former.

According to the Chronicle, discussions were held between the citizens and

Hardrada with a view to concluding a lasting peace, ‘provided that they all

marched south with him to conquer the country’.

Having been favourably received in York and won the support

of its citizens, the Norwegians withdrew to their ships at Riccall. Before they

set out to conquer the south, however, it had been agreed that there would be

another meeting, at which hostages from the rest of Yorkshire would be handed

over. For reasons that remain obscure, the location selected for this meeting

was neither Riccall nor York, but a small settlement eight miles to the east of

the city, a crossing of the River Derwent known as Stamford Bridge. Hardrada

and Tostig were waiting there on 25 September in expectation of a final round

of submissions before they advanced to subdue the rest of the kingdom.

What they encountered in the event was Harold Godwineson at

the head of a new royal army. The English king had advanced northwards and

reassembled his host far more quickly than his opponents had anticipated. After

leaving London around the middle of the month, he had arrived in the Yorkshire

town of Tadcaster on 24 September, having covered the intervening 200 miles in

little more than a week. According to the Chronicle, he had expected to find

Tostig and Hardrada holding York against him and had drawn up his forces

against an attack from that direction. But the following morning he discovered

that his brother and the Norwegian king had left for their appointment at

Stamford Bridge, evidently quite oblivious to his approach. It was an

opportunity not to be missed. Harold marched his men straight through York and

out towards the crossing on the Derwent, a distance of some eighteen miles. The

day must already have been well advanced by the time the English king fell upon

his unsuspecting enemies.

The accounts of the Battle of Stamford Bridge are not much

better than those for the encounter at Fulford five days before. Snorri is once

again on fine (i.e. unreliable) form, giving an account of the preliminaries

entirely at odds with that of the Chronicle, including an improbable interview

between the two King Harolds before the onset of hostilities (notably for its

oft-quoted line that Hardrada would be granted only ‘seven feet of ground’).

One element of Snorri’s account which does merit attention, however, is his

claim that the Norwegians had gone to Stamford Bridge wearing their helmets and

carrying their weapons, but without their mail shirts because the weather was

warm and sunny. Special pleading, you might think, but the story is

corroborated by a contemporary chronicler called Marianus Scotus. The C version

of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contributes a few more details, confirming that

the English king caught his enemies ‘unawares’, describing the fighting as

‘fierce’ and adding that it lasted until late in the day. It concludes with a

story, added in the twelfth century and repeated by several other writers, of

how the English were for some time prevented from crossing the bridge over the

Derwent by a single Norwegian warrior, apparently wearing a mail shirt, until

at length an inspired Englishman sneaked under the bridge and speared the Viking

in the one place where such armour offers no protection. This was supposedly

the turning point of the battle: Harold and his forces surged over the

undefended bridge and the rest of the Norwegian army were slaughtered. Both

Hardrada and Tostig were among the fallen.

It was, said the D Chronicle, ‘a very stubborn battle’. When

the remaining Norwegians tried to flee back to their ships at Riccall, the

English attacked them as they ran. Some drowned, says the Chronicle, some burnt

to death, and others died in various different ways, so that in the end there

were very few survivors. The author of the Life of King Edward, weeping for the

death of Tostig, wrote of rivers of blood: the ‘Ouse with corpses choked’, and

the Humber that had ‘dyed the ocean waves for miles around with Viking gore’.

Only those who made it back to Riccall – the D Chronicle names Hardrada’s son,

Olaf, among them – were given any quarter, their lives spared in exchange for a

sworn promise never to return. Above all, the scale of the Norwegian defeat is

indicated by the Chronicle’s comment that it took just twenty-four ships to

take the survivors home.

After the battle, the bodies of thousands of Englishmen and

Norwegians were left in the field where they had fallen; more than half a century

later, Orderic Vitalis wrote that travellers could still recognize the site on

account of the great mountain of dead men’s bones. But the body of Tostig

Godwineson was recovered from the general carnage and carried to York for an

honourable burial; William of Malmesbury, who had a fondness for such human

details, reports that it was recognized on account of a wart between the

shoulder blades (the implication being that all the earl’s other distinguishing

features had been too badly maimed). His older brother, it is as good as

certain, also returned to York in the aftermath of his victory. Apart from

anything else, he would have wanted to have a serious conversation with its

citizens about the alacrity they had shown in supporting his Norwegian namesake.

Quite possibly, therefore, Harold Godwineson was present at Tostig’s funeral,

whipped by the wind that continued to blow from the north.

Two days after the battle, however, the wind changed direction.

[note]

There was, of course, no such thing as standard spelling in

the eleventh century, so to some extent the modern historian can pick and

choose. I have, however, tried to be consistent in my choices and have not

attempted to alter them according to nationality: there seemed little sense in having

a Gunhilda in England and a Gunnhildr in Denmark. For this reason, I’ve chosen

to refer to the celebrated king of Norway as Harold Hardrada rather than the

more commonplace Harald, so his first name is the same as that of his English

opponent, Harold Godwineson. Contemporaries, after all, considered them to have

the same name: the author of the Life of King Edward, writing very soon after

1066, calls them ‘namesake kings’.