On 17 April 1942, RAF Bomber Command mounted one of the most

audacious missions of the Second World War. The target was the Maschinenfabrik

Augsburg-Nürnberg (MAN) diesel engine factory at Augsburg in Bavaria, which was

responsible for the production of roughly half Germany’s output of U-boat

engines. The Augsburg raid, apart from being one of the most daring and heroic

ever undertaken by Bomber Command, was notable for two main things: it was the

longest low-level penetration made during the war, and it was the first mission

flown by the command’s new Lancaster bombers in the teeth of strong enemy

opposition.

The prototype Avro Lancaster had been delivered to the RAF

for operational trials with No. 44 Squadron at Waddington, near Lincoln, in

September 1941. On 24 December it was followed by three production Lancaster Mk

Is, and the nucleus of the RAF’s first Lancaster squadron was formed. In

January 1942 the new bomber also began to replace the Avro Manchesters of No.

97 Squadron at Coningsby, another Lincolnshire airfield.

Four aircraft of No. 44 Squadron carried out the Lancaster’s

first operation on 3 March 1942, laying mines in the German Bight, and the

first night bombing mission was flown on 10 March when two aircraft of the same

squadron took part in a raid on Essen. In all, fifty-nine squadrons of Bomber

Command were destined to equip with the Lancaster before the end of the war,

and this excellent aircraft was to become the sharp edge of the RAF’s sword in

the air offensive against Germany. Developed from the twin-engined Manchester,

whose Rolls-Royce Vulture engines were disastrously unreliable, the Lancaster

was powered by four Rolls-Royce Merlins, the splendid engines that also powered

Fighter Command’s Spitfires and Hurricanes. It carried a crew of seven and had

a defensive armament of ten 0.303-in Browning machine-guns. It had a top speed

of 287 mph (460 kph) at 11,500 ft (3,500 metres) and could carry a normal bomb

load of 14,000 lb (6.350 kg) – although later versions could lift the massive

22,000 lb (10,000 kg) ‘Grand Slam’ bomb, used to attack hardened targets in the

last months of the war.

Because of the growing success of Hitler’s U-boats in the

Atlantic, the MAN factories at Augsburg had long been high on the list of

priority targets. The problem was that getting there and back involved a round

trip of 1,250 miles (2,000 km) over enemy territory, and the factories covered

a relatively small area. With the navigation and bombing aids available

earlier, the chances of a night attack pinpointing and destroying such an

objective were very remote, and a daylight precision attack, going on past

experience, would be prohibitively costly.

Then the Lancaster came along, and the idea of a

deep-penetration precision attack in daylight was resurrected. With its

relatively high speed and strong defensive armament, it was possible that a

force of Lancasters might get through to Augsburg if they went in at low level,

underneath the German warning radar. Also, a Lancaster flying ‘on the deck’

could not be subjected to attacks from below, its vulnerable spot. A lot would

depend, too, on the route to the target. RAF Intelligence had compiled a

reasonably accurate picture of the disposition of German fighter units in

western Europe, which early in 1942 were seriously overstretched. Half the

total German fighter force was deployed in Russia and another quarter in the

Balkans and North Africa; most of the remaining squadrons, apart from those

earmarked for the defence of Germany itself, were stationed in the Pas de Calais

area and Norway. The danger point was the coast of France; if the Lancasters

could slip through a weak spot, perhaps in conjunction with a strong

diversionary attack, then the biggest danger, in theory at least, would be

behind them.

Although Bomber Command’s new chief, Air Marshal Arthur

Harris, was generally opposed to small precision raids, being a strong advocate

of large-scale ‘area’ attacks on enemy cities, the situation in the North

Atlantic, with its awful daily toll of Allied shipping, compelled him to

authorize the Augsburg plan. If it succeeded, it might reduce the number of

operational U-boats for some time to come, and at the same time silence those

in high places who were clamouring for RAF Bomber Command to divert more of its

resources to hunting them.

The operation was to be carried out by six crews from No. 44

Squadron at Waddington and six from No. 97, now at Woodhall Spa in

Lincolnshire, the two most experienced Lancaster units. A seventh crew from

each squadron would train with the others, to be held in reserve in case

anything went wrong at the last minute.

For three days, starting on 14 April 1942, the two squadrons

practised formation flying at low level, making 1,000 mile (1,600 km) flights

around Britain and carrying out simulated attacks on targets in northern

Scotland. It was exhausting work, hauling thirty tons of bomber around the sky

at such an altitude and having to concentrate on not flying into a neighbouring

aircraft as well as obstacles on the ground, but the crews were all very

experienced, most of them going through their second tour of operations, and

they achieved a high standard of accuracy in the short time available.

Speculation ran high about the nature of the target. To most

of the crews, a low-level mission signified an attack on enemy warships, a

long, straight run into a nightmare of flak. When they eventually filed into

their briefing rooms early on 17 April, and saw the long red ribbon of their

track stretching to Augsburg, a stunned silence descended on them. Almost

automatically, they registered the details passed to them by the briefing

officers. The six aircraft from each squadron were to fly in two sections of

three, each section leaving the rendezvous point at a predetermined time. The

interval between each section would be only a matter of seconds; visual contact

had to be maintained so that the sections could lend support to one another in

the event that they were attacked by enemy fighters.

From the departure point, Selsey Bill, the Lancasters were

to cross the Channel at low level and make landfall at Dives-sur-Mer, on the

French coast. Shortly before this, bombers of No. 2 group, covered by a massive

fighter ‘umbrella’, were to make a series of diversionary attacks on Luftwaffe

airfields in the Pas de Calais, Rouen and Cherbourg areas. The Lancasters’

track would take them across enemy territory via Ludwigshafen, where they would

cross the Rhine, to the northern tip of the Ammer See, a large lake some 20

miles (30 km) west of Munich and about the same distance south of Augsburg. By

keeping to this route, it was hoped that the enemy would think that Munich was

the target. Only when they reached the Ammer See would the bombers sweep

sharply northwards for the final run to their true objective.

As they approached the target, the bombers were to spread

out so that there was a 3 mile (5 km) gap between each section. Sections would

bomb from low level in formation, each Lancaster dropping a salvo of four 1,000

lb (454 kg) bombs. These would be fitted with eleven-second delayed-action

fuzes, giving the bombers time to get clear but exploding well before the next

section arrived over the target. Take-off was to be in mid-afternoon, which

meant that the first Lancasters should reach the target at 20.15, just before dusk.

They would therefore have the shelter of darkness by the time they reached the

Channel coast danger-areas on the homeward flight. The fuel tanks of each

aircraft would be filled to their maximum capacity of 2,154 gal (9,792 litres).

The Lancasters of No. 44 Squadron would form the first two

sections. This unit was known as the ‘Rhodesia’ Squadron, with good reason:

about a quarter of its personnel came from that country. There were also a

number of South Africans, and one of them was chosen to lead the mission. He

was Squadron Leader John Dering Nettleton, a tall, dark 25-year-old who had

already shown himself to be a highly competent commander, rock-steady in an

emergency. The war against the U-boat was of special interest to him, for after

leaving school in Natal he had spent two years in the Merchant Navy and

consequently had a fair idea of the agonies seamen went through when their

ships were torpedoed. He came from a naval background, too: his grandfather had

been an admiral in the Royal Navy. John Nettleton joined the Royal Air Force in

1938, and in April 1942 he was still completing his first operational tour. It

was one of the penalties of being an above-average pilot: such men were often

‘creamed off’ to teach others.

Shortly after 15.00 on 7 April, the quiet Lincolnshire

village of Waddington was shaken by the roar of twenty-four Rolls-Royce Merlins

as No. 44 Squadron’s six Lancasters took off and headed south for Selsey Bill,

the promontory of land jutting out into the Channel between Portsmouth and

Bognor Regis. Ten miles (15 km) due east, the six bombers of No. 97 Squadron,

led by Squadron leader J.S. Sherwood DFC, were also taking off from Woodhall

Spa.

Each section left Selsey Bill right on schedule, the sea

blurring under the Lancasters as they sped on. The bombers to left and right of

Nettleton were piloted by Flying Officer John Garwell and Warrant Officer G.T.

Rhodes; the Lancasters in the following section were flown by Flight Lieutenant

N. Sandford, Warrant Officer H.V. Crum and Warrant Officer J.E. Beckett. The

sky was brilliantly clear and the hot afternoon sun beat down through the

perspex of cockpits and gun turrets. Before they reached the coast, most of the

crews were flying in shirt sleeves.

As they raced over the French coast the pilots had to ease

back their control columns to leapfrog the cliffs, so low were the bombers.

They thundered inland across the picturesque landscape of Normandy, the broad

loops of the River Seine glistening in the sunshine away to the left. The

bombers would pass to the south of Paris and on to Sens, on the Yonne River,

their first major checkpoint. Sens lay about 180 miles (290 km) from the

Channel coast – about an hour’s flying time, at the ground speed the Lancasters

were making. If they survived that first hour, if the diversionary raids had

drawn off the German fighters, then they would have a good chance of reaching

Augsburg.

The bombers were flying over wooded, hilly country near

Breteuil when the flak hit them. Lines of tracer from concealed gun positions

met the speeding Lancasters, and the ugly black stains of shellbursts dotted

the sky around them. Shrapnel ripped into two of the aircraft, but they held

their course. The most serious damage was to Warrant Officer Beckett’s machine,

which had its rear gun turret put out of action.

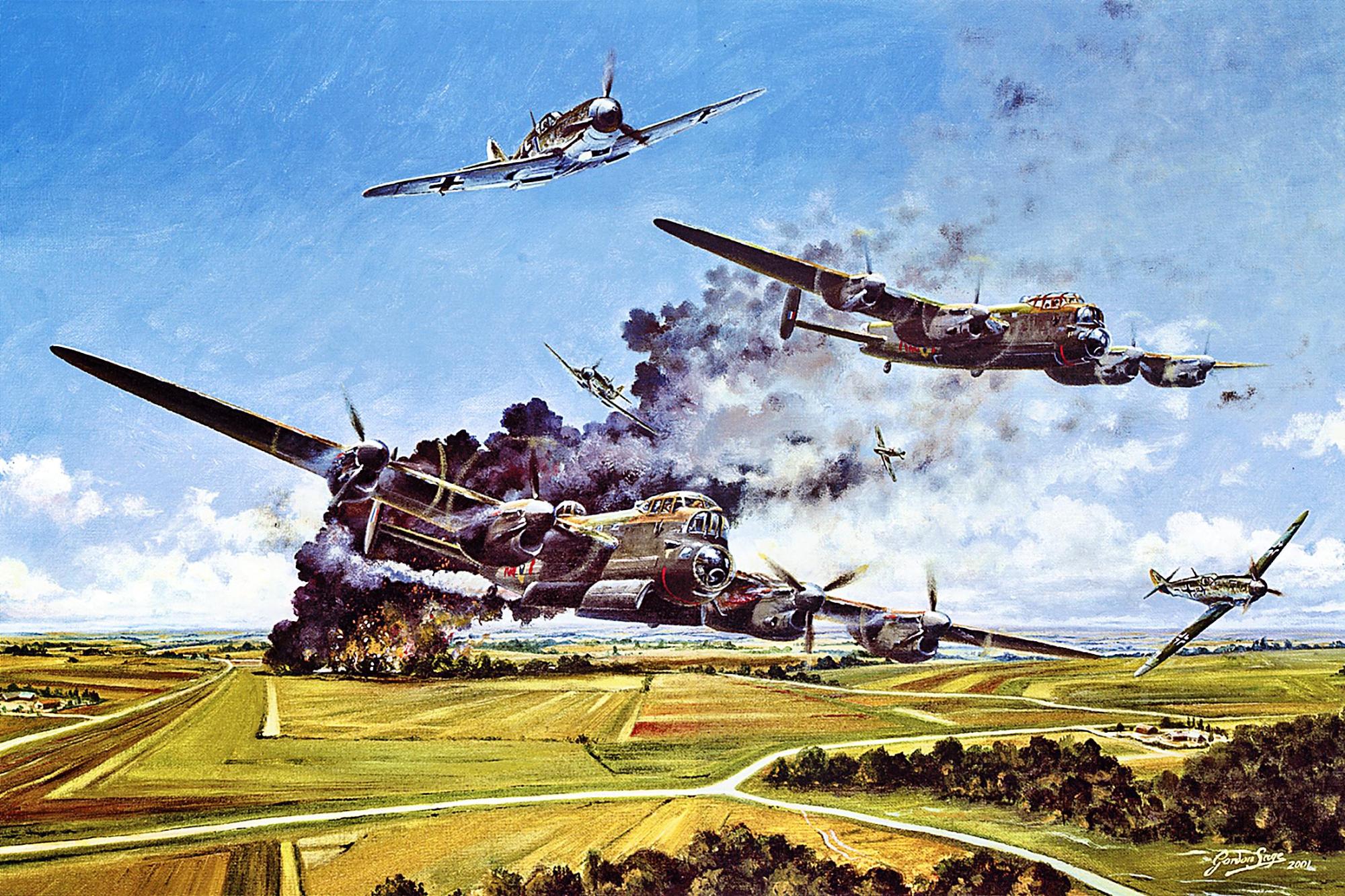

It was sheer bad luck that drew the German fighters to the

Lancasters. The Messerschmitt Bf 109s of II/Jagdgeschwader 2 ‘Richthofen’ were

returning to their base at Evreux after sweeping the area to the south of Paris

in search of No. 2 Group’s diversionary bombers when they passed directly over

the Lancasters’ track, actually passing between Nettleton’s and Sherwood’s

formations, although at a much higher altitude. Even then, the bombers might

have escaped detection had it not been for a solitary Messerschmitt 109, much

lower than the rest, making an approach to land at Evreux with wheels and flaps

down.

The German pilot spotted the Lancasters and immediately

whipped up his flaps and landing gear, climbing hard and turning in behind

Sandford’s section. He must have alerted the other fighters, because a few

seconds later they came tumbling like an avalanche on the bombers.

The first 109 came streaking in, the pilot singling out

Warrant Officer Crum’s Lancaster for his first firing pass. Bullets tore

through the cockpit canopy, showering Crum and his navigator, Rhodesian Alan

Dedman, with razor-sharp slivers of perspex. Dedman looked across at the pilot

and saw blood streaming down his face, but when he went to help Crum just

grinned and waved him away. The Lancaster’s own guns hammered, there was a

fleeting glimpse of the 109’s pale-grey, oil-streaked belly as it flashed

overhead, and then it was gone.

The Lancasters closed up into even tighter formation as

thirty more Messerschmitts pounced on them, and a running fight developed. The

Lancaster pilots held their course doggedly; at this height there was no room

to take evasive action and they had to rely on the bombers’ combined firepower

to keep the Germans at bay. It was the first time that Luftwaffe fighters had

encountered Lancasters, and to begin with the enemy pilots showed a certain

amount of caution until they got the measure of the new bomber’s defences. As

soon as they realized that its defensive armament consisted of 0.303 in

machine-guns, however, they began to press home their attacks skilfully, coming

in from the port quarter and opening fire with their cannon at about 700 yards

(640 m). At 400 yards (366 m), the limit of the .303’s effective range, they

broke away and climbed to repeat the process.

The Lancasters were raked time after time as they thundered

on, their vibrating fuselages a nightmare of noise as cannon shells punched

into them and the gunners returned the enemy fire, their pilots drenched with

sweat as they dragged the bombers over telegraph wires, steeples and rooftops.

In the villages below, people fled for cover as the battle swept over their

heads and shells from their own fighters spattered the walls of houses.

Warrant Officer Beckett was the first to go. A great ball of

orange flame ballooned from his Lancaster as cannon shells found a fuel tank.

Seconds later, the bomber was a mass of fire. Slowly, the nose went down.

Spewing burning fragments, the shattered bomber hit a clump of trees and disintegrated.

Warrant Officer Crum’s Lancaster, its wings and fuselage

ripped and torn, came under attack by three enemy fighters. Both the mid-upper

and rear gunners were wounded, and now the port wing fuel tank burst into

flames. The bomber wallowed on, almost out of control. Crum, half-blinded by

the blood streaming from his face wounds, fought to hold the wings level and

ordered Alan Dedman to jettison the bombs, which had not yet been armed. The

1,000- pounders dropped away, and a few moments later Crum managed to put the

crippled aircraft down on her belly. The Lancaster tore across a wheatfield and

slewed to a stop on the far side. The crew, badly shaken and bruised but

otherwise unhurt, broke all records in getting out of the wreck, convinced that

it was about to explode in flames. But the fire in the wing went out, so Crum

used an axe from the bomber’s escape kit to make holes in the fuel tanks and

threw a match into the resulting pool of petrol. Within a couple of minutes the

aircraft was burning fiercely; there would only be a very charred carcase left

for the Luftwaffe experts to examine.

Afterwards, Crum and his crew split up into pairs and set

out to walk through occupied France to Bordeaux, where they knew they could

make contact with members of the French Resistance. All of them, however, were

subsequently rounded up by the Germans and spent the rest of the war as

prisoners.

Now only Flight Lieutenant Sandford was left out of the

three Lancasters of the second section. A quiet music-lover who amused his

colleagues because he always wore pyjamas under his flying suit for luck, he

was one of the most popular officers on No. 44 Squadron. Now his luck had run

out, and he was fighting desperately for his life. In a bid to escape from a

swarm of Messerschmitts, he eased his great bomber down underneath some

high-tensions cables. The Lancaster dug a wingtip into the ground, cartwheeled

and exploded, killing all the crew.

The enemy fighters now latched on to Warrant Officer Rhodes,

flying to the right of and some distance behind John Nettleton. Soon, the

Lancaster was streaming fire from all four engines. Rhodes must have opened his

throttles wide in a last attempt to draw clear, because his aircraft suddenly

shot ahead of Nettleton’s. Then it went into a steep climb and seemed to hang

on its churning propellers for a long moment before flicking sharply over and

diving into the ground. There was no chance of survival for any of the crew.

The Lancaster was shot down by another warrant officer, a

man named Pohl. Poor Rhodes was the thousandth victim to be claimed since

September 1939 by the pilots of JG 2, and a party was held in Pohl’s honour at

Evreux that night.

There were only two Lancasters left out of the 44 Squadron

formation now: those flown by Nettleton and his number two, John Garwell. Both

aircraft were badly shot up and their fuel tanks were holed, but the

self-sealing ‘skins’ seemed to be preventing leakage on a large scale.

Nevertheless, the fighters were still coming at them like angry hornets, and the

life expectancy of both crews was now measured in minutes.

Then the miracle happened. Suddenly, singly or in pairs, the

fighters broke off their attacks and turned away, probably running out of fuel

or ammunition, or both. Whatever the reason, their abrupt withdrawal meant that

Nettleton and Garwell were spared, if only for the time being. They still had

more than 500 miles (800 km) to go before they reached the target. Behind them,

and a little way to the south, Squadron Leader Sherwood’s 97 Squadron formation

had been luckier; they never saw the German fighters, and flew on unmolested.

Flying almost wingtip to wingtip, Nettleton and Garwell

swept on in their battle-scarred aircraft. There was no further enemy

opposition, and the two pilots were free to concentrate on handling their

bombers – a task that grew more difficult when, two hours later, they

penetrated the mountainous country of southern Germany and had to fly through

turbulent air currents that boiled up from the slopes. They reached the Ammer See

and turned north, rising a few hundred feet to clear some hills and then

dropping down once more into the valley on the other side. And there, dead

ahead under a thin veil of haze, was Augsburg.

As they reached the outskirts of the town, a curtain of flak

burst across the sky in their path. Shrapnel pummelled their wings and

fuselages but the pilots held their course, following the line of the river to

find their target. The models, photographs and drawings they had studied at the

briefing had been astonishingly accurate and they had no difficulty in locating

their primary objective, a T-shaped shed where the U-boat engines were

manufactured.

With bomb doors open, and light flak hitting the Lancasters

all the time, they thundered over the last few hundred yards. Then the bombers

jumped as the 8,000 lb (3,600 kg) of bombs fell from their bellies. The

Lancasters were already over the northern suburbs of Augsburg when the bombs

exploded, and the gunners reported seeing fountains of smoke and debris

bursting high into the evening sky above the target.

Nettleton and Garwell had battled their way through

appalling odds and successfully accomplished their mission, but the flak was

still bursting around them and now John Garwell found himself in trouble. A

flak shell turned the interior of the fuselage into a roaring inferno and

Garwell knew that this, together with the severe damage the bomber had already

sustained, might lead to her breaking up at any moment. There was no time to

gain height so that the crew could bale out; he had to put her down as quickly

as possible. Blinded by the smoke that was now pouring into the cockpit,

Garwell eased the Lancaster gently down towards what he hoped was open ground.

He was completely unable to see anything; all he could do was try to hold the

bomber steady as she sank.

A long, agonizing minute later the Lancaster hit the ground,

sending earth flying in all directions as she skidded across a field. Then she

slid to a stop and Garwell, with three other members of his crew, scrambled

thankfully out of the raging heat and choking, fuel-fed smoke into the fresh

air. Two other crew members were trapped in the burning fuselage and a third,

Sergeant R.J. Flux, had been thrown out on impact. He had wrenched open the

ecape hatch just before the bomber touched down; his action had given the

others a few precious extra seconds in which to get clear, but it had cost Flux

his life.

Completely alone now, John Nettleton set course

northwestwards for home, chasing the afterglow of the setting sun. As he did

so, the leading section of No. 97 Squadron descended on Augsburg. They had to

fly through a flak barrage even more intense than the storm that had greeted

Nettleton and Garwell; as well as four-barrelled 20 mm Flakvierling cannon, the

Germans were using 88 mm guns, their barrels depressed to the minimum and their

shells doing far more damage to the buildings of Augsburg than to the racing

bombers. All three Lancasters released their loads on the target and thundered

on towards safety, their gunners spraying any AA position they could see. The

bombers were so low that on occasions they dropped below the level of the

rooftops, finding some shelter from the murderous flak.

Sherwood’s aircraft, probably hit by a large-calibre shell,

began to stream white vapour from a fuel tank. A few moments later flames

erupted from it and it went down out of control, a mass of fire, to explode

just outside the town. Sherwood alone was thrown clear and survived. The other

two pilots, Flying Officers Rodley and Hallows, returned safely with their

crews.

The second section consisted of Flight Lieutenant Penman,

Flying Officer Deverill and Warrant Officer Mycock. All three pilots saw

Sherwood go down as they roared over Augsburg in the gathering dusk. The sky

above the town was a mass of vivid light as the enemy gunners hurled every

imaginable kind of flak shell into the Lancasters’ path. Mycock’s aircraft was

quickly hit and set on fire but the pilot held doggedly to his course. By the

time he reached the target his Lancaster was little more than a plunging sheet

of flame, but Mycock held on long enough to release his bombs. Then the

Lancaster exploded, its burning wreckage cascading into the streets.

Deverill’s Lancaster was also badly hit and its starboard

inner engine set on fire, but the crew managed to extinguish the blaze after

bombing the target and flew back to base on three engines, accompanied by Penman’s

Lancaster. Both crews expected to be attacked by night fighters on the home

run, but the flight was completely uneventful. It was just as well, for every

gun turret on both Lancasters was jammed.

For his part in leading the Augsburg raid, John Nettleton

was awarded the Victoria Cross. He was promoted to the rank of wing commander,

and the following year saw him flying his second tour of operations. He was

killed on the night of 12/13 July 1943, his bomber falling in flames from the

night sky over Turin, Italy.

Altough reconnaissance later showed that the MAN assembly

shop had been damaged, the full results of the raid were not known until after

the war. It appeared that five of the delayed-action bombs which the Lancaster

crews had braved such dangers to place on the factory had failed to explode.

The others caused severe damage to two buildings, one a forging shop and the

other a machine-tool store, but the machine-tools themselves suffered only

light damage. The total effect on production was negligible, especially as the

MAN had five other factories building U-boat engines at the time.

The loss of seven Lancasters and forty-nine young men was

too high a price to pay. Not until the closing months of 1944 would the RAF’s

four-engined heavy bombers again venture over Germany in daylight, and by then

the Allied fighters ruled the enemy sky.