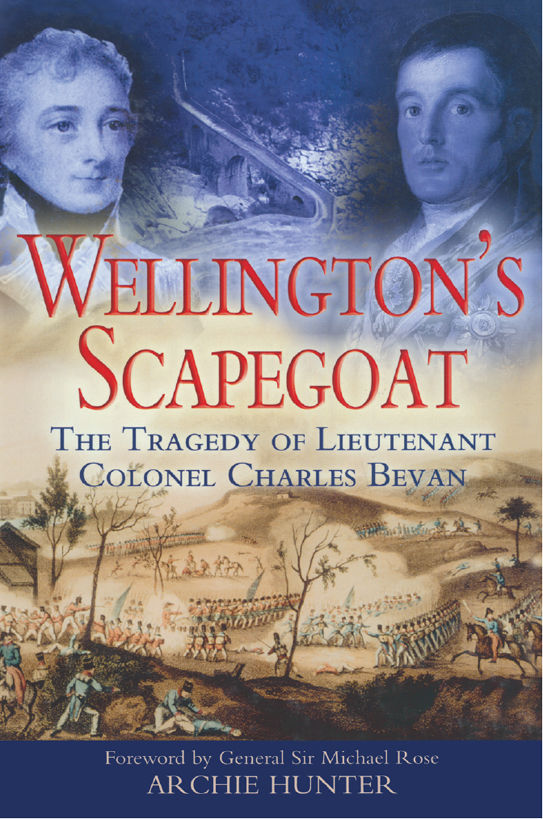

WELLINGTON’S SCAPEGOAT: The Tragedy of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bevan by Archie Hunter (Author)

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bevan was the key figure in an extraordinary, controversial and ultimately tragic episode during the Peninsula War. He was the commanding officer held responsible for the dramatic night escape of the French garrison from Almeida over a vital bridge. For this disaster he incurred the extreme wrath of the Duke of Wellington but whether this was fair remains highly debatable.

Drawing on letters and papers of the Bevan family and other contemporary sources this book examines the background to Wellington’s order to defend the bridge; the subsequent blame heaped upon Bevan for the part played by him and his Battalion; and the very questionable role of the incompetent, drunken, General Erskine in the affair. It tells of Wellington’s acceptance of Erskine’s version of events and then his obstinacy, even poor judgement, in refusing Bevan’s request for an inquiry. Finally there is lead up to Bevan’s suicide directly related to his and his Regiment’s honour being unjustly tarnished by Wellington.

The book also covers the six earlier campaigns in which Bevan served with distinction before joining Wellington in Portugal, and so builds a picture of his competent character and military experience.

Scapegoat of the Peninsula

July 1811

On 8 July 1811, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Bevan, commanding

the 4th of Foot, died of fever in the town of Portalegre on the border between

Portugal and Spain. On the 11th, his funeral took place with full military

honours. The officers of the battalion attended, with a firing party of four

captains, eight subalterns and 300 rank and file, under command of Major

Tanner, the second in command. His grave was bricked over and a stone placed at

the head bearing this description:

This stone is erected to the Memory of Charles Bevan

Esqre,

Late Lt. Col of the 4th or King’s Own Regt.

With the intention of recording his virtues.

They are deeply engraved on the hearts and minds of all

who knew him.

Sadly, this was a complete fabrication. There is no trace of

his grave or headstone in Portalegre, Portugal. There is no record in local

documents and no residual memory handed down to present-day inhabitants. It was

a complete cover-up, the truth of which was not revealed until 1843.

The Peninsula War, which lasted from 1808 to 1814, was only

part of the twenty-year struggle against Napoleon but an important aspect of

it, to the extent that Bonaparte famously described it as the ‘Spanish ulcer’.

For him, indeed, that is what it turned out to be.

Essential to the British effort, as in many conflicts before

and since, was control of the sea. Not only was this vital to protect our

shores and guard the resupply chain for the troops in the Iberian Peninsula,

but it also enabled Britain to attack the French outlying territories with

impunity. In 1800, Britain effectively stood alone and on the defensive.

Napoleon had set out to conquer the Middle East and, though halted in Egypt, he

was still paramount throughout Europe. Indeed, from 1803 to 1805 there was a

serious threat of invasion as Napoleon had assembled a shipping armada in the

Channel ports with a ground force of some 160,000 troops, quite capable of

mounting a seaborne assault.

However, frustrated by his inability to control the Channel

sufficiently to achieve this, he decided to cripple Britain’s economy by

forbidding any European country over which he had control or influence from

trading with it. Portugal, a maritime nation with close ties to Britain,

refused to comply, and Napoleon sent Marshal Junot with 28,000 men through

Spain to Portugal to teach it a lesson. The French reached Lisbon in November

1807.

In the spring of the following year, 75,000 Frenchmen

invaded Spain. Joseph, Napoleon’s brother, was placed on the throne. The

populations of both Portugal and Spain were enraged and rose against the

invader, asking Britain for help. Overestimating the extent and effectiveness

of the rebellion, the government agreed to become involved.

The small Spanish Army was badly trained and unpredictable

but contained many brave men and officers. Time and again in the coming years

their troops would try to take on Napoleon’s armies and generally they were

routed; only on a few occasions were they successful. However, a more effective

erosion of the French effort was achieved by guerrillas who conducted what was

to become a classic of that kind of warfare: hit and run with small bands,

constantly harassing rearguards and supply lines and, effectively, tying down

troops who were badly needed elsewhere. The Spanish became such masters of this

kind of combat that, it was said, it took the French 200 cavalry to guard a

vital messenger and 1,000 men to ensure the safety of a general travelling

round the country.

An essential factor in Wellington’s strategy was that he had

the support of the local population whereas the French had to be constantly on

their guard against marauding bands and received no local supplies without

seizing them and no local intelligence. Even if entering a town or village

without being attacked, their troops were largely met with sullen non-cooperation.

Britain’s naval superiority now came to the fore. It allowed

the government to send a force to assist the Portuguese and Spaniards in August

1808, withdraw it from Corunna a few months later, and then replace it in April

1809. Throughout, this meant that in the coming campaign Wellington could

maintain a first-class commissariat, ensuring his troops, by the standards of

the day, were properly fed and armed. He also insisted his quartermasters paid

for local provisions, which the French were unable or unwilling to do. This was

critical to winning the ‘hearts and minds’ of the population.

At the same time, Wellington preserved his army by taking

few risks in the early years and fighting only when the odds were favourable by

ensuring the French were never able to concentrate large numbers against him.

He broke the French ciphers, had a network of agents and so often therefore had

better information than the French generals themselves. Although maps were

poor, good sketches were drawn and much of the ground had been ridden over a

number of times before a battle was actually fought there. So cover from view

and concealed approaches (‘dead ground’) were marked down and remembered.

In August 1808, the British, under Sir Arthur Wellesley, as

he then was, landed 80 miles north of Lisbon. Wellesley immediately set about

plans to evict the French from Portugal. However, he learned that as a mere

39-year-old he was to be superseded by a couple of senior, and elderly,

generals—the 58-year-old Sir Hew Dalrymple and 53-year-old Sir Harry Burrard,

neither of whom had recent operational experience. It was a political move, and

the sort which was to land Wellington with some incompetent commanders for much

of the time. He had to accept the decision but hoped to oust the French before

his seniors could arrive. He had some early success at Roliça and Vimeiro

before Burrard arrived and put a damper on further exploitation of these

achievements. Nevertheless, it was a nasty surprise for the French who were not

used to failure.

The controversial Convention of Cintra was signed between

the British and French in August. In it the French agreed to withdraw from

Portugal and return to France. However, what infuriated those at home were the

clauses that stipulated the French were to be returned home in British ships

and they were allowed to keep the booty they had looted from the Portuguese.

The generals, including Wellesley, were arraigned before a Court of Inquiry

accused of incompetence. Dalrymple was sacked and Burrard retired. Luckily,

Wellesley was cleared but was not immediately given another command.

In Wellesley’s absence, Lieutenant General Sir John Moore

was ordered to advance into Spain and drive the French back over the Pyrenees.

At the same time, Napoleon himself entered the fray and took command,

determined to sort out the British. After a certain amount of difficulty in

putting his reinforcements together, Moore realised that he was to be trapped

between two large French armies under Napoleon and Marshal Nicolas Soult, so,

to the disgust of his troops, withdrew to Corunna from where, Dunkirk-like,

they could be evacuated. The retreat was an exhausting and very tough three

weeks of constant rearguard actions against the harrying French, but they never

lost a gun or a set of Colours.

Napoleon, realising he was not going to be able to cut the

British off, left for Paris with better things to do and relinquished the

pursuit to Soult. Moore and his bedraggled troops finally made it into Corunna

in January 1809 to find no shipping awaited them. They turned and fought their

pursuers so successfully that they were actually forcing them back when Moore

was killed and the momentum faded. Boats arrived and 19,000 men were

successfully embarked and sailed for England to fight another day. It was the

nadir of British hope and expectation. Political morale at home was low and the

population thoroughly dissatisfied. The French were now back in northern

Portugal and in strength in Spain, although Lisbon itself was unoccupied, where

there were still some British troops. Additionally, southern Spain was still

not entirely subjugated.

Wellesley, however, was optimistic and put forward a plan to

occupy Portugal, from where he could launch a campaign into Spain. The grateful

British government endorsed his ideas with alacrity and he sailed for Portugal,

landing in Lisbon in April 1809. Wellesley had reshaped and reorganised the

army and began to restructure the Portuguese Army under British officers. He

realised that, with the three French armies a long way apart, he could take

them out piecemeal if he moved quickly; if they were allowed to join together

they would present an insuperable force. With lightning speed, Wellesley

crossed the river Douro and drove Soult’s army of 20,000 men into full retreat

out of Portugal and back into Spain, with the loss of all their baggage.

Wellesley now entered a difficult time with his Spanish

allies, some of whose generals resented him and his relative youth. By July,

Wellesley set up a defensive position north of Talavera. Although, on paper, he

outnumbered the French, he was dependent on the Spaniards whom he simply did

not trust. Talavera was a ferocious battle over two days with the British

losing over 5,000, and the Spanish 1,200, against the French 7,000. It was a

significant, but only tactical, victory for the British, with the French

withdrawing towards Madrid, but they had fought themselves to a standstill, run

out of supplies and were too exhausted to follow up. Wellesley deservedly

became Viscount Wellington.

Wellington always kept in his mind the safety of Portugal

behind him for resupply lines and seaborne protection, either for

reinforcement, repositioning along the coast or for Corunna-type evacuation if

necessary. So he was constantly anxious not to be cut off from his routes back.

Despite their setback at Talavera, the French remained a serious threat and

clearly Soult wanted to cut Wellington off from the Portuguese lifeline for the

same reasons Wellington wanted to preserve it. Consequently, Wellington

reconnoitred defensive positions north and west of Lisbon, which became known

as the Lines of Torres Vedras. Work began immediately and secrecy was such that

the French failed to discover them until they arrived a year later.

Soured by the difficulties of cooperating with the Spanish,

Wellington refused to collaborate with them in any military operation for the

remainder of 1809 and in December he withdrew back across the border into

Portugal to settle down for the winter. Very little happened the following year

until, in the autumn, the French invaded Portugal for the third time.

Wellington, though, had not wasted his time; reorganisation and streamlining of

his forces took place, particularly incorporating the Portuguese, contingency

plans were made and potential battle positions reconnoitred and intelligence

was quietly gathered. He even reached agreement with the Portuguese Government

over a scorched earth policy.

There are three main approach routes into Portugal from the

east. The central one was least likely to be used and Wellington left that to

General William Beresford to protect. The southern ran through Badajoz in Spain

and Elvas in Portugal to Lisbon and was the most direct. The northern, and most

likely, was through Ciudad Rodrigo in Spain to Almeida in Portugal. These

fortresses were in Allied hands. He took personal control of the northern

route, leaving ‘Daddy’ Hill, one of his most trusted generals, to guard the

southern corridor.

The French were now in a better position to reinforce the

Peninsula, having made peace with the Austrians. Masséna, one of Napoleon’s

ablest generals, was ordered to drive the British out but, even though he was

given overall command, he still had to receive instructions from Paris, which

because of the time delay stifled initiative. However, in July and August both

Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida fell to the French, but it was not to go all their

way. Wellington had long planned his defence on the Bussaco Ridge and, in

September, soundly defeated Masséna’s assaults. It was a tactical victory in

which, for the first time, the Portuguese troops played a significant part.

Rather than pursuing the French, he stuck to his original plan and withdrew in

good order to the Lines of Torres Vedras. From there, Wellington could take on

Masséna’s renewed attacks on his own terms. Masséna had been unaware of the

strength, or even existence, of the Lines and very soon gave up but not as

quickly as Wellington had hoped. The rapid fall of Almeida meant that the

French had advanced much faster than expected and so the scorched earth policy

proved less effective than it should have been. There was nothing Masséna could

do that winter, so he withdrew, losing some 25,000 to disease and starvation.

The die was set and the French never again were in a position to drive the

British into the sea.

In the south, the British in Cadiz had been happily tying

down a considerable force of French who were besieging them. It was decided in

March 1811, though, to make a daring breakout by sea, with an Anglo-Spanish

force, land behind the French besiegers and attack them. The Spanish failed in

their part of the operation, leaving the British outnumbered and isolated at

Barrosa, but with a bold counter-attack they succeeded in defeating the enemy.

Meanwhile, in the north, Wellington was closely pursuing the

weak and demoralised French, who had now withdrawn back into Spain leaving a

garrison in the Portuguese fortress of Almeida. Unfortunately, Soult had

captured Badajoz, so both main lines into Spain were now in the hands of the

enemy. Wellington ordered Beresford to besiege Badajoz but, realistically,

there was little chance of success with Soult threatening him from the south.

Masséna, having regrouped much more swiftly than anticipated, now pushed westwards

from Ciudad Rodrigo to relieve the blockaded Almeida. Wellington set up his

defence around Fuentes de Oñoro on ground he knew well. The French were beaten

off in a battle over three days. But then came the French garrison escape from

Almeida: ‘the most disgraceful military event that has yet occurred to us’,

stormed Wellington.

We now turn to the main player in this disaster. Charles

Bevan was born in 1778 into a well-to-do middle-class family. He had a happy

family life with a brother and two sisters. Luckily for historians, he was also

an assiduous letter writer. In 1795, he purchased a commission in the 37th

Regiment of Foot (later the Hampshire Regiment). This was common practice at

the time but advance was also by immediate promotion on the battlefield through

some act of bravery or literally filling dead men’s shoes after a campaign when

vacancies occurred. Hence there was never any lack of volunteers for the

‘Forlorn Hope’—the spearhead of any assault when survival by itself was pretty

much a guarantee of promotion. It also helped to have the eye/ear of a senior

and influential general who could often nudge things in the right direction.

Bevan was very aware of this. His first overseas posting, by now a lieutenant,

was to Gibraltar, where he remained for three and a half years. After a period

with his regiment, he was made aide-de-camp (ADC) to Lieutenant General William

Grinfield. While he would have missed some of the excitements his

contemporaries were having at the time, he would have been noticed by important

people his general was meeting and it would have done his career no harm.

In March 1800, no doubt itching to see action, he bought

himself a vacancy as a captain in the 28th Regiment of Foot (later the

Gloucestershire Regiment). While these line regiments perhaps lacked a little

of the glamour of the green-jacketed light infantry, such as Harry Smith’s

famous 95th (later the Rifle Brigade after Waterloo) or the Foot Guards, they

were very steady regiments with dependable NCOs and countrymen in the ranks.

Later, of course, in the reforms of 1881, they were to be based on counties and

deliberately recruited from them. Bevan was blessed in his new regiment with an

outstanding commanding officer in the person of Lieutenant Colonel Edward

Paget, fourth son of Lord Uxbridge, who was to have a very successful later

career and, indeed, influence over Bevan’s. For a time he served in Minorca

with the regiment as the island was again in British hands. It had been lost in

1756 through Admiral Byng’s failure (see Chapter 3) but had been returned to

Britain under the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1763 following the Seven

Years War. Ceded back to Spain in 1783 by the Treaty of Versailles, Britain

invaded yet again in 1798 (the 28th were in this action) and resumed occupation

of this important base controlling the Mediterranean Sea. Bevan was now, at

last, to get his first taste of action.

Napoleon had invaded Egypt in 1798, not only to help control

the eastern Mediterranean and establish a colony but also to provide a corridor

and main supply route into India with the eventual aim of annihilating the

British there. However, the virtual destruction of his fleet at the Battle of

the Nile curtailed these aspirations and, instead, he set about making himself

ruler of Egypt in his characteristic egotistical style. Meeting strong

resistance, and with Turkey and Russia now taking the field against France,

Napoleon returned home to the chagrin of his troops left behind. A British

force commanded by Lord Abercromby had been ordered to the Mediterranean in May

1800. He captured Malta and, in October that year, it was planned to use his

army to expel the French from Egypt. The British, supported by a small Ottoman

army, would land on the Egyptian coast. A second, larger Ottoman army would

invade through Palestine, while a third British force, made up of troops from

India and reinforced from Britain, would land on the Red Sea coast and march

down the Nile to Cairo.

Abercromby’s force arrived at Aboukir Bay, where a

determined assault commanded by Sir John Moore succeeded in establishing a

beachhead. Bevan was in the assault force and was severely wounded together

with his commanding officer, Edward Paget. The Battle of Alexandria took place

in March and by the end of April the main British Army, combined with the

Ottomans, advanced on Cairo. They reached the city in June, and after a short

siege the French surrendered. General Hutchinson, who had replaced Abercromby,

defeated the remaining French in Alexandria and the occupation of Egypt was

over. Bevan recovered from his wounds and took command of the Light Company of

the battalion, a specific honour, no doubt in recognition of his performance in

the invasion. The 28th left for home towards the end of 1802 but not before its

men were given the distinction of wearing a smaller version of their cap badge

on the back of their headdress. They had been attacked by the French cavalry

during the battle before Alexandria on 21 March 1801. They were in line and

there being no time to form square, the commanding officer ordered the rear

rank to ‘Right about face’ and they succeeded in beating off the enemy. Such is

the stuff of regimental tradition.

Paget became a brigade commander in October 1803 and,

recognising Bevan’s quality, made him his brigade major. This position is, in

essence, the chief executive of the brigade and, as such, is the senior staff

officer. Then, as now, it is a sought-after job by those looking for high-grade

employment and with an eye on promotion. The brigade, with both battalions of

the 28th under command, was stationed in Fermoy, north of Cork in Ireland.

Before this, Bevan had met his future wife, Mary, the daughter of Admiral

Dacres. From his letters to her, he was clearly deeply in love and they were

engaged in 1804. Although Mary’s letters to him have not survived, there is

much in his that reflects her words to him and clearly they have considerable

rapport.

He finishes a letter to her of 27 May 1804, ‘I am very

anxious to compare your picture with yourself, as on a more intimate

acquaintance with it I begin to fancy it very like—my dearest love! I have a

thousand things to say to you and plans to propose—which if realised!! But it

is impossible to write on these subjects as I fear my imagination, perhaps too

ardent, may lead me to hope what, for your dear sake must not be—I hardly need

tell you what this is—Now, how can I ever part with you.’

Paget then commanded a brigade in Folkestone, taking Bevan

with him. The threat of French invasion was very real so Bevan was unable to

get away to visit his fiancée in Plymouth. However, his ambitions were being

met by his purchase of a majority in the same regiment. This, no doubt, put him

in a good light with his future father-in-law, and Mary and he were married in

December 1804. Return to regimental duty meant rejoining his battalion in

Ireland with his new wife.

Early wedded bliss was, however, not to last long. A

coalition (the third) between Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia sought to

defeat Napoleon on the Continent. The French, having given up the idea of

invading England, now concentrated on Central Europe. Lord Cathcart,

commander-in-chief in Ireland, was ordered to command an expedition to Hanover.

Paget’s brigade, with the 28th including Bevan under command, arrived near

Bremen in late 1805 to be part of the force to expel the French from Hanover

and recover northern occupied territory. It was a relatively half-hearted

operation, let down by the Prussians who made peace with the French in January

1806, leaving the British no option but to re-embark for England soon

afterwards. Napoleon’s victories at Ulm and Austerlitz could hardly have helped

British morale. William Pitt produced one of his most famous quotes at the

time: ‘Roll up that map [of Europe], it will not be wanted these ten years’.

Nelson, however, had completed the Royal Navy’s mastery of the sea at Trafalgar

in October 1805, which gave some comfort.

Bevan was now reunited with his family and at regimental

duty in Colchester. However, even when on manoeuvres, Bevan would take every

opportunity to write to his wife. On 24 June 1807, he wrote, ‘We still remain,

my beloved Mary, in uncertainty as to the period of our embarkation but we have

received orders to practise some particular things relating principally to

Continental Service. . . . I am very well only my unfortunate Face is quite

skinned by the sun. We have every morning Field Day for about 3 hours in the

heat of the day. But it will soon get seasoned and then I shall do very well.’

In July 1807, there were two Treaties of Tilsit between the

French and, firstly, Russia and, secondly, Prussia, thereby isolating Britain,

with its sole ally Sweden, even further. Denmark, at the time not formally

allied to any power, had a considerable navy. Britain was concerned that

Napoleon would occupy Denmark, seize its shipping and force it to close the

Baltic, vital to Britain for ships’ naval stores material and access to Sweden.

Additionally, Britain was uneasy about the Danes’ loyalty having failed to

persuade them into an alliance. Consequently, a naval force, with a land

element embarked under Lord Cathcart, was put to sea to monitor the Danish

fleet.

On 16 August, the troops were landed, unopposed, north of

Copenhagen. Bevan’s regiment took part in the relatively low-level operations

against the Danes. It was difficult for the British really to regard the Danish

as foes and the actions were not pressed home with the customary vigour.

However, Cathcart was forced to bombard Copenhagen city as it refused to

surrender and much unnecessary destruction resulted. A military success, having

neutralised the Danish Navy, but a diplomatic failure as it, unsurprisingly,

drove the Danes into the arms of the French. Nevertheless, the Swedes remained

implacably anti-Napoleon and refused his demands to close the Baltic ports.

Bevan and his regiment returned home hardly to a heroes’ welcome.

The consequence was that Finland, then part of Sweden, was

invaded by Russia, while Prussia and Denmark declared war on Sweden. Britain,

thoroughly alarmed that Napoleon might take advantage of this and launch an

attack on Sweden through Denmark, decided to send an expeditionary force to

Sweden under Sir John Moore. The aim of this undertaking was not entirely clear

except, perhaps, to demonstrate solidarity with the Swedes, but it was not an

operation of war. To Bevan’s delight, his regiment, also interestingly in the

same brigade as the 4th Regiment of Foot, was again under Edward Paget, by now

a divisional commander. The force set sail in May 1808 but lay idle for weeks,

cooped up in their transport ships anchored off the Swedish coast. The whole

expedition was a muddle and complete waste of time and resources. The Swedish

king had insane ideas of how the British force was to be used and Sir John

Moore, though summoned to Stockholm for ‘consultations’, was having none of it.

In a letter to Mary of 2 June 1808, Bevan tells her he had

been ill but, on recovery, managed to go ashore with Paget’s ADC and see some

of the country. Rumours were rife, even that the force was to sail for Buenos

Aires. The fleet, however, returned to Spithead in July but, to everyone’s

frustration and disappointment, no one was allowed to disembark (imagine the

uproar nowadays!) and fresh orders were issued for the force to sail direct for

Portugal. The Peninsula War had started.

Bevan was a great admirer of Sir John Moore, having seen how

he trained his troops when they were stationed not far away in Kent in 1804. So

now, being under his command in Portugal must have been very heartening. There

have been observations that his letters to Mary contained elements of moaning

and a suspicion of depression. However, this is not untypical of soldiers

stationed far from home, critical of the way they think the war is being run,

exasperation with their leaders or, simply, missing their wives and families.

It is fortunate that so many letters and accounts were written at this time,

not only by officers but also by many rank and file as well. Much of their

content echoes Bevan’s, so not too much should be made of it.

Still in the 28th Regiment of Foot and, to his continuing

exasperation, a major (‘Thirty years old & alas! Still a Major’), Bevan’s

battalion was at full strength and well regarded by Moore. They were all keen

to chase the French out of Spain. There was much optimism and self-confidence

but the reality was that they knew very little of Spain and even less about

French strengths and dispositions. Bevan and his men faced some hard marching

and by November were in Ciudad Rodrigo, which he appeared to like, then later

in Salamanca, which he didn’t. Being unaware, like much of the army, of the

difficult choices facing Moore, Bevan was keen to be on the move to face the

French and, in December 1808, happily, started to move north-east. However,

after a small-scale victory when Bevan was in reserve in Paget’s division,

Moore decided to pull back to avoid entrapment. Thus began the long slog back

to Corunna.

Sadly, there is no evidence of what happened to Bevan during

the retreat. Understandably, he cannot have had time to write to Mary, or, if

he did, the few letters that he would have been able to write have not

survived. We do know his battalion was in the Reserve Division, which meant

that it would often find itself fighting rearguard actions against the pursuing

French. This is not an attractive operation even by today’s standards—trying to

protect the rear of a withdrawing force but judging the exact moment to break

clean from the enemy oneself. Even the great ‘Black Bob’ Craufurd would make a

mess of such a manoeuvre with his famous Light Division on the Côa in July of

1810. Embarkation from Corunna under continual French pressure was difficult

but successful for Bevan and the 28th, who reached England in January 1809 in a

pretty poor state.

Soon after this major setback, the British again sent an

expeditionary force to the Continent, this time to the Scheldt in Holland in

1809. This was the biggest amphibious operation of the Napoleonic war with some

40,000 men embarked. The short distances enabled such a large force to be

deployed and supplied. Scheldt was a key strategic objective with the hope that

its capture would have an impact on Napoleon’s attack on the Austrians as well

as take out the docks at Antwerp. Bevan, now back to his normal form, left with

his battalion on 28 July. The voyage was made with agreeable companions,

reasonable food and interesting discussion. Little did they know what awaited

them. The Walcheren Expedition was one of the most ignominious military

episodes of the time. The intention was to assist the Austrians, now allies,

against Napoleon by forcing him to look north. The immediate aim was to destroy

the French fleet in Flushing. However, before the British even landed, the

Austrians had been beaten at Wagram and were out of the war. Nevertheless, the

British went ashore and captured Flushing only to find that the French fleet

had been moved out of harm’s way to Antwerp. Severe sickness in the form of a

kind of malaria set in, decimating the British ranks. Over 4,000 troops died,

of which only 106 did so in combat. The residual effect of Walcheren fever was

to persist in the battalions that had been exposed to it throughout the rest of

the war. The force was withdrawn in September.