Akhenaten died soon after his attack on Kadesh, but the

question of what to do about the area of Kadesh did not go away. The Hittite

counterattack into the Egyptian territory of Amki breached the Egyptian-Hittite

treaty of the time, but was probably no more than a retaliatory raid; as far as

the sources indicate, Suppiluliuma did not follow with a major Hittite

offensive. Major events in Syria-Palestine for most of the reign of Tutankhamun

remain unknown, since Tutankhamun’s abandonment of Akhet-aten brought the

Amarna archive to an immediate halt; wherever Tutankhamun’s diplomatic

correspondence was stored-Thebes or more likely Memphis-the record lies as yet

undiscovered. No Egyptian or Hittite historical texts unequivocally record any

battles in Syria-Palestine prior to the final year of Tutankhamun’s reign, but

at about the time of the death of Tutankhamun, another Egyptian campaign was

launched against Kadesh; details do not survive, but the timing of the Egyptian

attack might have been intended to coincide with a Mittani counteroffensive.

The renewed attacks of the weakened but still existent state of Mittani

precipitated the Second Syrian War, also known as the Six-Year Hurrian War,

which culminated in the defeat of Carchemish and the complete destruction of

the Mittanian state. Tutankhamun’s strike on Kadesh triggered a Hittite

counterattack on Amki, the same reaction Akhenaten’s attack on Kadesh had

elicited. Both Akhenaten and Tutankhamun probably sought to force some

conclusion to the Kadesh problem, for with the last vestige of the Hurrian

state expunged, Hatti might decide to use Kadesh and the corridor east of

Amurru.

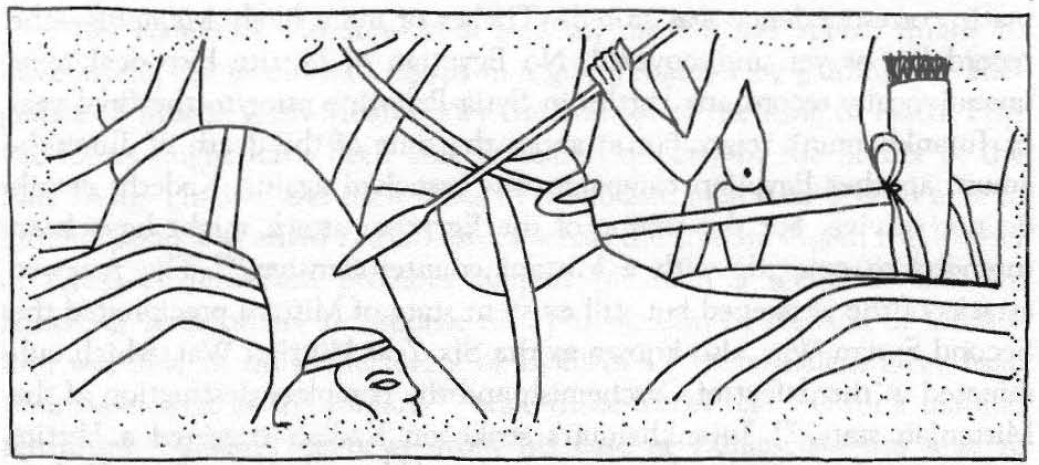

The images of Tutankhamun’s Asiatic campaign are fragmentary

and provide few details about the location of the battle or the tactics involved.

Despite these problems, the lively carvings indicate that a chariot battle and

an assault on fortifications were elements of the campaign. In one scene, an

Asiatic warrior, with a typical bobbed hairstyle and kilt, is transfixed by the

spear of an Egyptian charioteer. The ancient artist heightened the drama of the

combat by showing the dead Asiatic draped across the legs of Egyptian chariot

horses. Another block from this same tableau depicts an Asiatic tangled in the

reins of his own chariot. In addition to the chariot battle, Tutankhamun’s

reliefs also depict an attack against fortifications. On one block, an Egyptian

soldier armed with a spear, his shield slung across his back, ascends a ladder propped

against a crenellated wall. The figure of a bearded Asiatic falling headlong from

the fortress suggests the success of the Egyptian assault.

Two blocks from battle scenes of Tutankhamun’s Asiatic campaign. (top) A charioteer, with the horse’s reins tied behind his back, spears an Asiatic enemy, whose body falls across the legs of the horses. The shield-bearer wears a heart. shaped sporran and stands in front of a full quiver of arrows. After Johnson, Asiatic Battle Scene, 156, no. 10. (bottom) A soldier, armed with a spear and a shield, climbs a ladder resting against the battlements of an Asiatic stronghold, while an enemy defender falls to the ground. After Johnson, Asiatic Barrie Scene, 157. no. 12.

The Asiatic War scenes of Tutankhamun portray two different

types of enemies, suggesting that the Egyptians fought a coalition of forces

from throughout Syria-Palestine. The southern, Canaanite type have a short

beard, a bobbed hairstyle tied with a fillet, and wear kilts. The northern

Syrian or Mitannian type have short hair, a long beard, and wear long cloaks.

The Tutankhamun battle scenes also provide a small but significant bit of

information about the chariots of the “boy-king’s” enemies. A poorly

preserved block from the Tutankhamun Asiatic battle scene appears to depict a

three-man crew in an Asiatic chariot. The Asiatics against whom Tutankhamun

fights are depicted as standard Canaanite types, not as Hittites, The

Syro-Palestinians, as they appear in scenes of foreign tribute in the tomb of

the vizier Rekhmire, in the heraldic image of Asiatic combat on the chariot of

Thutmose IV, and the Hittites in the later war tableaux of Seti I, routinely

appear with chariots virtually identical to those of the ancient Egyptians, and

like the Egyptians, the Asiatics appear to have assigned two men to a chariot.

The image of three Asiatic men in a chariot from the

Tutankhamun monument recalls the later three-man chariots of the Hittites in

the scenes of the Battle of Kadesh under Ramesses II. At Karnak, when Seti I

depicted his encounter with the Hittites, he shows the Hittites fighting and dying

with chariots manned by two men, similar to the Egyptian chariots. When Seti’s

successor Ramesses II depicts the chariotry swarms of his own Hittite enemies,

those Hittite chariots have three-man crews. Were it not for the Tutankhamun

block, one might suggest that the Hittites simply adopted a new style of

chariot, perhaps as a result of their loss to the forces of Seti I. The Tutankhamun

scene reveals that some sort of experimentation with a different type of

chariot crew, and almost certainly with a different sort of chariot, was

already occurring during the reign of Tutankhamun.

Why would the Syro-Palestinian enemies of Tutankhamun or the

Hittite opponents of Ramesses II add an extra man to the chariot crew? The

added weight forced the Hittites to make their vehicles heavier, sacrificing

both speed and maneuverability. The Hittite chariotry that attacked Ramesses II

also appear to have shifted away from the use of chariots to carry archers;

instead, the Hittite chariot crews consist of a driver, a shield-bearer, and a

warrior armed with a spear or a lance, both weapons with ranges much shorter

than that of the composite bow. While the Egyptian chariot was still suited for

high-speed engagement as a platform for mounted archers, the makers of the Hittite

chariots had sacrificed the potential for abrupt turns at speed, and seem

uninterested in the vehicle’s properties of maneuver. The Hittite chariot

warriors of the Kadesh battle scenes appear to have become mounted infantry,

the chariot transforming into a type of battle taxi; the apparent three-man

chariot in the Tutankhamun battle scene suggests that experimentation with the

chariot as battle taxi could well go back at least as far as the Amarna Period.

The impetus for this apparent shift in chariot tactics, from mobile archery platform

to battle taxi, remains to be explored.

The inscriptions accompanying the scenes of the Battle of

Kadesh indicate that the Hittites secured soldiers from throughout their

empire, including the western marches. From the western edge of the Hittite

realm may have come the chief impetus for the three-man chariot. The groups who

harassed the western borders of Hatti fought as massed infantry, appear as the

Ahhiyawa in the Hittite record, and are one of the groups the Egyptians

included among the Sea Peoples. The chariot forces of the day, armed primarily

with bows, had difficulty defeating the Ahhiyawa and other Sea People groups

who wore armor and wielded close-combat weapons. The placement of Hittite

infantry soldiers within the new three-man chariots was probably intended to

make the chariotry more effective against the new Sea People foes. Considering

the pressures on the Hittites in the west, and taking into account particular

facets of the subsequent invasions of Egypt from the west and the north, the

three-man chariot from the Tutankhamun battle scene is the swallow that heralds

the dawn of the rise of massed infantry.

Fragments of relief from the mortuary temple of Horemhab

contain further images of an Asiatic campaign. Since Horemhab was responsible

for the actual military command and Tutankhamun may have even died while the

campaign was in progress, Horemhab probably felt no compunction about taking

credit for the victory, as he had for the Nubian War he also led for

Tutankhamun. Without further evidence, the warfare in Syria-Palestine depicted

on the monuments of Horemhab most probably took place entirely during the reign

of Tutankhamun.

Images of the battle on blocks reused from Horemhab’s

mortuary temple include the royal chariot (only the names of the horses

survive) and Egyptian charioteers shooting arrows and surrounded by slain

Asiatic foes. At least two of the Asiatics have only a single hand-the stumps

of their right arms indicate that their hands have already been severed to

provide an accurate count of the enemy dead. Another block depicting part of

the battlements of a city labeled “Fortress which his Majesty captured in

the land of Kad[esh]” provides the setting for this Asiatic battle.

Other reliefs from Tutankhamun’s Theban memorial chapel show

the triumphal return of the Egyptian military by sea. The royal flagship, with

dozens of rowers and a large two-level cabin decorated with a frieze of uraeus

serpents, also carries an important piece of cargo: an Asiatic captive. This

Asiatic appears in a cage hanging from the yardarm of the ship, a secure prison

that allows Tutankhamun to display his military success. Unfortunately, no text

accompanies this scene, and one can only speculate about the identity of the

unfortunate captive. Earlier, Amunhotep III had Abdiashirta, the unruly Amorite

leader, brought back to Egypt, and Tutankhamun may have copied this feat with

the ruler of Kadesh, which would make the man in the cage Aitakama. In this

case, while Akhenaten was not militarily successful, Tutankhamun’s attack on

Kadesh would have achieved at least one major objective.

Block (rom the mortuary temple of Horemhab. An

Egyptian chariot team rides into battle against Asiatic foes. While the helmeted

charioteer shoots his bow, the shield-bearer holds aloft a round-topped shield.

The chariot is equipped with a bow case (the limp flap indicates that it is now

empty) and has a six·spoked wheel and hand, hold on the body. Fallen Asiatics

and charioteers’ helmets litter the scene. The right portion of the block was

recarved at a later date. After Johnson, Asiatic Battle Scene, 170, no. 50.

Tutankhamun also commemorated the results of the

Syro-Palestinian war on the eastern bank at the temple of Karnak. In a relief

in the court between the Ninth and Tenth pylons, Tutankhamun presents the

spoils of victory to the Theban triad. Stacked before the king are elaborate

metal vessels and other products from western Asia. Behind Tutankhamun are

Asiatic prisoners, all bound by ropes that the king holds in his hand. The

dress and coiffure of the captives indicate their diverse origins-some are from

inland Syria-Palestine, while at least one is probably an Aegean islander or

nautical type of the eastern Mediterranean. In a parallel scene, Tutankhamun

presents tribute from Punt, accompanied by the high chiefs of the Puntites.

However, the chiefs of Punt are not bound, but stride freely, presenting the

produce of their country. The differences between the representations of the

Asiatics and the Puntites demonstrate their contrasting relationships with

Egypt. While the inhabitants of Syria-Palestine represent chaotic forces that

must be subdued, the Puntites, who inhabited a land far southeast of Egypt,

peacefully traded with the Nile Valley. Although some of the Asiatics led bound

behind the pharaoh lived closer to Egypt than the distant land of Punt, they

were ideologically much farther from the ordered world that was Egypt.

The tomb that Horemhab commissioned while a general provides

further depictions of the results of Tutankhamun’s Asiatic War. Rows of bound

Asiatic prisoners appear alongside Nubians and Libyans on the east wall of the

second courtyard; the only accompanying text speaks of General Horemhab’s

victories in all foreign lands: “His reputation is in the [land] of the

Hittites(?), after he trave led northward.” The questionable mention of

the Hittites in this text finds further support in two images from Horemhab’s

tomb that represent the first depictions of Hittites from their Anatolian

homeland, otherwise known from the battle reliefs of Seti I. The south wall of

that same courtyard contains exquisitely carved reliefs of more Asiatic

prisoners; the manacles-some of them elaborately carved to resemble rampant

lions-and ropes binding the men advertise their status as prisoners of war, and

the emotion-filled expressions of the men indicate their reactions to their new

status. Horemhab, who is called “one in attendance on his lord upon the

battlefield on this day of smiting the Asiatics,” leads these prisoners before

the enthroned royal couple, Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun.

In addition to the scenes of Asiatic prisoners, the tomb of

Horemhab also contains images of other foreigners from all corners of the

world- Libyans, Nubians, and Asiatics. In these scenes, the different

ethnicities are juxtaposed, and none of the foreigners is bound. These two

types of scenes reflect two separate historical events. The reliefs of the

unbound foreigners allude to a durbarlike event, such as that depicted in two

of the tombs at Amarna and in the tomb of Huy, and the incorporation of foreign

captives into the Egyptian military. The gathering of foreigners appearing in

vivid detail in the tomb of Horemhab may even represent the same northern and

southern durbars as appear in the tomb of the viceroy Huy. On the other hand,

the scenes of bound Asiatics correspond to a specific military event.

Unfortunately, the general lack of toponyms in the tomb prevents a precise

determination of the origin of the Asiatic prisoners, but one may reasonably

suggest that they were captured during Tutankhamun’s attack on Kadesh.