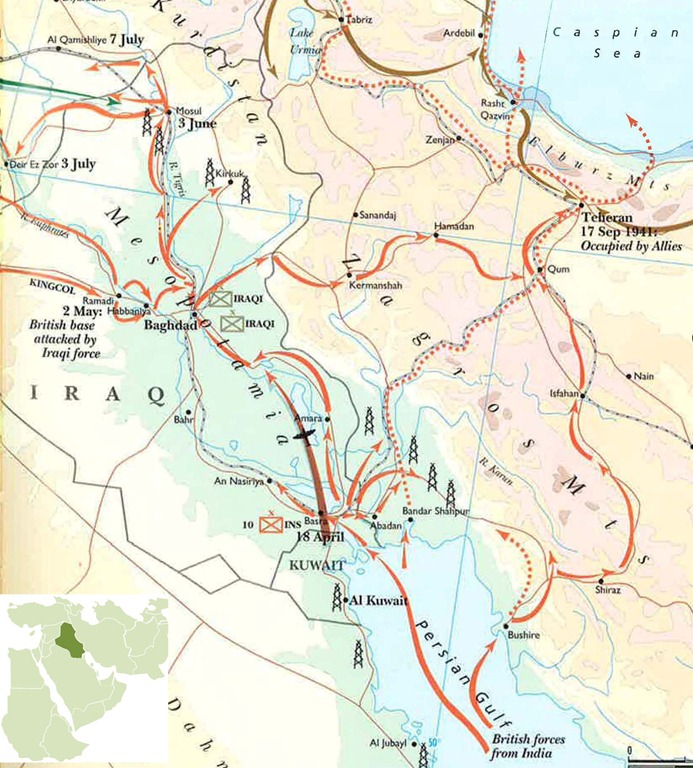

In May 1941, British forces were fighting to keep Iraq in Allied hands — a struggle that belatedly involved German and Italian aircraft as well.

By Kelly Bell

At 2 a.m. on April 30,

1941, officials in the British Embassy in Baghdad were awakened by Iraqi

military convoys rumbling out of the Rashid Barracks, across bridges and into

the desert toward the Royal Air Force (RAF) training base near the Iraqi town

of Habbaniya. They immediately sent wireless signals to the air base’s ranking

commander, Air Vice Marshal Harry George Smart. With his base not set up or

prepared for combat, Smart initially could think of little to do other than

sound the general alarm — neglecting to announce the reason. The base speedily

degenerated into a madhouse of scared, sleep-sodden, bewildered cadets,

instructors and sundry other personnel.

In the spring of 1941,

the RAF’s No. 4 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) at Habbaniya held just 39

men who knew how to fly an airplane. As May began, however, those instructors

— few of whom had combat experience — and their students found they were the

principal obstacle to a military operation that might well have brought Britain

to its knees.

There are those who

call the fight for Habbaniya airfield the second Battle of Britain. Fought half

a year after the exhaustively chronicled 1940 air campaign that blunted German

hopes of neutralizing or conquering England, this Mideastern shootout was at

least as crucial to the outcome of World War II — yet few have heard of it.

The prize over which

the campaign raged was crude oil. Although Britain had granted Iraq

independence in 1927, the British empire still maintained a major presence

there, since Britain’s oil jugular passed through that Arab kingdom. On April

3, 1941, militant anti-British attorney Rashid Ali el Gailani led a coup d’état

that set him up as chief of the National Defense government. This Anglophobic

barrister’s dearest ambition was to expel by military force all Englishmen from

the Middle East. He set about enlisting the assistance of like-minded Egyptians

who vaguely promised to organize an uprising of their army in Cairo. He

contacted German forces in Greece — which had just fallen to the Third Reich

— to inform them of his intentions and solicit their support. He also let Maj.

Gen. Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, newly arrived in Libya, know they

could count on the support of pro-Axis Vichy French forces in Syria to provide

easy access to Iraq. Finally, he told the Germans he would secure for them unrestricted

use of all military facilities in Iraq, whether or not they were held by the

British.

Until Rashid Ali’s

coup, British forces in the region — falsely comforted by the 1927 treaty, by

which Iraq and the United Kingdom were technically bound as allies —

anticipated little trouble beyond scattered anti-British riots by civilians.

Rashid Ali’s pro-Axis overtures set Prime Minister Winston Churchill at odds

with his commander in the Middle East, General Sir Archibald Wavell. Wavell

insisted that he had his hands full as it was, between evacuating Greece,

preparing for an expected German invasion of Crete and dealing with Rommel’s

recent North African offensive. Churchill recognized the threat that an Axis

inroad in Iraq would pose to the empire. It could deprive Britain of crude oil

from the fields in northern Iraq, sever its air link with India and encourage

further anti-British uprisings throughout the Arab mandates.

As a first response,

the 2nd Brigade of the 10th Indian Division landed at Basra on the night of

April 29, with the rest of the division soon to follow, along with the aircraft

carrier Hermes and two cruisers. On learning of that development, Rashid

Ali mobilized his Iraqi army and air force supporters and dispatched them to

seize Habbaniya air base.

Situated on low ground

next to the Euphrates River less than 60 miles from Baghdad, Habbaniya was

overlooked 1,000 yards to the south by a 150-foot-high plateau. Beyond that was

Lake Habbaniya, from which British flying boats evacuated the base’s civilian

personnel, including women and children, on April 30. The base’s cantonment

housed 1,000 RAF personnel and the 350-man 1st Battalion of the King’s Own

Royal Regiment. There were also 1,200 Iraqi and Assyrian constabulary organized

in six companies, but the British could only rely on the four companies of

Assyrian Christians, who devoutly hated Iraqis of different extraction. Aside

from 1st Company, RAF Armoured Cars, with its 18 outdated Rolls-Royce vehicles,

the principal weaponry available to the base was its aircraft, the most potent

of which were nine obsolete Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters and a Bristol

Blenheim Mk.I bomber. The other planes at the school comprised 26 Airspeed

Oxfords, eight Fairey Gordons and 30 Hawker Audaxes. Aside from the

unsuitability of its aircraft for combat, Habbaniya’s greatest vulnerability

lay in its dependence on a single electric power station that powered the pumps

necessary to supply its base with water.

During the chaos

following the alarm, the Iraqis arrived and set up artillery along the plateau

running along the far side of the base’s landing field. This was a ghastly

surprise for Air Vice Marshal Smart, who sent out an Audax trainer to

reconnoiter at daybreak on April 30. The crew’s initial report was that the

highlands were alive with what looked like more than 1,000 soldiers with

fieldpieces, aircraft and armored vehicles. At 6 a.m. an Iraqi officer appeared

at the camp’s main gate and handed over a letter that read: “For the

purpose of training we have occupied the Habbaniya Hills. Please make no flying

or the going out of any force of persons from the cantonment. If any aircraft

or armored car attempts to go out it will be shelled by our batteries, and we

will not be responsible for it.”

Such comportment of

forces on a “training exercise” struck Smart as disquietingly

inappropriate, so he typed out the following reply for the courier: “Any

interference with training flights will be considered an ‘act of war’ and will

be met by immediate counter-offensive action. We demand the withdrawal of the

Iraqi forces from positions which are clearly hostile and must place my camp at

their mercy.”

Smart next had his

ground crews dig World War I–style trenches and machine gun pits around the

base’s seven-mile perimeter, pathetic defenses against aerial attack and

shelling from elevated positions. That left the cadets and pilots to arm, fuel

and position their aircraft in 100-degree heat. The young men shoved their

planes into the safest possible locations — behind buildings and trees, where

they were still vulnerable.

Habbaniya’s RAF base

commander, Group Captain W.A.B. Savile, divided his airplanes into four

squadrons. The Audaxes were organized as A, C and D squadrons, under Wing

Commanders G. Silyn-Roberts, C.W.M. Wing and John G. Hawtrey, respectively. B

Squadron, under Squadron Leader A.G. Dudgeon, operated 26 Oxfords, eight

Gordons and the Blenheim. In addition to the squadrons, Flight Lt. R.S. May led

the Gladiators as a Fighter Flight from the polo ground. Although most of the

planes were old, there were an impressive number of them. Of the 35 flying

instructors on hand, however, only three had combat experience, and there were

even fewer seasoned bombardiers and gunners. Smart selected the best of the

cadets to bolster those numbers, while the ground crews installed racks and

crutches for 250-pound and 20-pound bombs on the trainers.

On the evening of

April 30, the British ambassador to Iraq radioed Smart that he regarded the

Iraqi actions up to that point as acts of war and urged Smart to immediately

launch air attacks. He also reported he had informed the Foreign Office in

London of the Habbaniya situation and that His Majesty’s diplomats both in

Baghdad and London were urging the Iraqis to withdraw — without response.

Habbaniya received

four more wireless messages in the small hours of May 1. First, the ambassador

promised to support any action Smart decided to take, although Smart would

likely have preferred to have a high-ranking military figure giving him that

backing. Second, the commander in chief, India (Habbaniya was still part of

India Command), advised Smart to attack at once. The third dispatch was from

the British commander in Basra, announcing that because of extensive flooding

he could send no ground forces, but would try to provide air support. Smart

finally heard from London: The Foreign Office — again, civilians — authorized

him to make any tactical decisions himself, on the spot.

Meanwhile, by May 1

the Iraqi forces surrounding Habbaniya had swelled to an infantry brigade, two

mechanized battalions, a mechanized artillery brigade with 12 3.7-inch

howitzers, a field artillery brigade with 12 18-pounder cannons and four

4.5-inch howitzers, 12 armored cars, a mechanized machine gun company, a mechanized

signal company and a mixed battery of anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns. This

totaled 9,000 regular troops, along with an undetermined number of tribal

irregulars, and about 50 guns.

Supporting those

ground forces were elements of the Royal Iraqi air force, including 63 British,

Italian and American-built warplanes equal to or newer than those at Habbaniya.

Number 1 (Army Co-operation) Squadron at Mosul had 25 airworthy Hawker Nisrs,

export variants of the Audax powered by Bristol Pegasus radial engines. Number

4 (Fighter) Squadron at Kirkuk possessed nine Gladiators. At Baghdad No. 5

(Fighter) Squadron had 15 Breda Ba.65 attack planes, while at Rashid No. 7

(Fighter-Bomber) Squadron could field 15 Douglas 8A-4s, as well as four Savoia

S.M.79B twin-engine bombers purchased from Italy in 1937. On paper, at least,

the Iraqi air force had the RAF outclassed at Habbaniya.

Smart contacted his

ambassador in Baghdad to issue an ultimatum for the Iraqis to start withdrawing

from Habbaniya by 8 a.m. on May 2. In that way should they refuse to heed the

deadline, the whole day would be available for combat. Smart was still unsure

of how far London would support him if he engaged the armed forces of a country

not clearly defined as an Axis power. His maddening uncertainty was tardily

banished by a May 1 telegram from Churchill: “If you have to strike,

strike hard.”

That emboldened the

harried commander to make the first move. He had learned from a radio message

that 10 Vickers Wellington bombers from No. 70 Squadron had arrived at Basra.

With expectations of their support, he would launch an airstrike at dawn on May

2. Although an aerial assault against well-dug-in armored forces had never

succeeded before, Smart was upbeat, remarking, “They should be in full

retreat within about three hours.”

Smart refused to

withdraw the aircrewmen and least-experienced students from the trenches

despite their doubtful ability, even bolstered by 400 Arab auxiliaries, to stop

an armored charge. Knowing that their ground crews’ availability to service

returning machines would be critical in the fight to come, Smart’s squadron

commanders furtively toured the perimeter late on the night of May 1 and led

the necessary personnel away from their fighting positions.

At 4:30 on the morning

of May 2, 1941, the first flying machine cranked its engines on Habbaniya

airfield. Thirty minutes later 35 Audaxes, Gordons and Oxfords were showering

bombs on the Iraqis, joined by Wellingtons of Nos. 70 and 37 squadrons from

Basra. The Iraqis were well dug-in on broken ground that provided good cover

and concealment, so the British saw few potential targets at first. The Iraqis,

unable to draw beads on the airplanes in the darkness, retaliated by shelling

the air base, but the gun flashes gave away their positions. The Audaxes

dropped explosives on the anti-aircraft gun pits while the Wellingtons’ turret

gunners strafed them. The Iraqi anti-aircraft gunners used many tracers, again

marking their positions for the British airmen to attack or avoid. After bombing

from just 1,000 feet for maximum accuracy, the British carefully scanned the

plateau for suitable future targets.

As soon as an aircraft

landed, one of its two crewmen (they alternated) would hurry to the operations

control room, report on the results of his raid and suggest targets for the

next flight. Meanwhile, the other crew member would oversee ground personnel in

making repairs, refueling and rearming the aircraft. The planes’ engines were

generally kept running. As soon as the first crew member returned with a new

assignment, the two would board their machine and return to the fray.

The Wellingtons

performed well on the first day, but being big they attracted the eagle’s share

of groundfire as well as half-hearted attacks from two Iraqi Gladiators and two

Douglas 8As. One damaged “Wimpy” was forced to land at Habbaniya and

then set on fire by Iraqi artillery shells; nine other damaged bombers were

declared unserviceable when they returned to Basra. Groundfire brought down an

Oxford flown by Flying Officer D.H. Walsh, and Pilot Officer P.R. Gillespy’s

Audax failed to return.

Smart’s estimate that

the Iraqis would cut and run within three hours proved seriously

overoptimistic. By 12:30 p.m., after 7 1/2 hours of almost-constant aerial

assault, they were still shelling the base, and at 10 a.m. their air force had

joined in, destroying three aircraft on the airfield. One of the Gladiator

pilots, Flying Officer R.B. Cleaver, was trying to intercept an S.M.79B when

his guns failed, but Flying Officer J.M. Craigie caused a Ba.65 to break off

its strafing attack.

By day’s end, the

British had flown 193 recorded operational sorties — six per man. The RAF had

lost 22 of its 64 aircraft, and 10 pilots were dead or critically wounded, but

only a crippling injury was deemed sufficient to send a man to the infirmary.

Although the Iraqis

had been sorely hurt and showed no inclination to launch a ground attack, they

were still firmly ensconced atop their elevation with a variety of fieldpieces

trained on the smoking flying school. Furthermore, that afternoon Iraqi troops

invaded the British Embassy in Baghdad and confiscated every wireless

transceiver and telephone, leaving the only two significant English outposts in

the region isolated from each other.

By that evening,

Dudgeon and Hawtrey were the only squadron commanders not dead or hospitalized.

They decided that the next day Hawtrey would command all remaining Audaxes and

Gladiators from the base’s polo field, which was visually screened from the

artillery by a row of trees. Dudgeon would direct all Oxfords and Gordons from

the cratered landing field.

Meanwhile, the

Committee of Imperial Defense had transferred command of land forces in Iraq to

Middle East Command, compelling Wavell to assemble whatever elements he could

spare into a relief unit, called Habforce, to march the 535 miles from Haifa to

Habbaniya. Rashid Ali’s leaders also appealed for help, but the Germans were

preparing for their invasions of Crete and the Soviet Union, and the Italian

response was slow. Only the Vichy French in Syria agreed to send arms and

German-supplied intelligence to the Iraqis. They also promised the use of

Syrian airfields to any aircraft that the Germans or Italians were willing to

commit to Iraq.

On May 3, Smart,

noting that the Iraqi artillery had not caused as much damage as he feared it

would, called for the RAF to launch some preemptive strikes against the Iraqi

air bases. Three Wellingtons of No. 37 Squadron bombed Rashid, also claiming to

have shot down a Nisr and damaged another. The Iraqi airmen struck back, but

Cleaver attacked an S.M.79B, which he last saw diving away with its left engine

smoking. One of the Gordon pilots, Flight Lt. David Evans, developed a novel

and risky but effective method of dive-bombing. After the ground crewmen had

affixed fuzes with a seven-second delay to the 250-pound bombs, he would remove

the safety devices. That meant that if a bomb came loose from its fitting, it

would probably explode seven seconds later. After takeoff, Evans would climb to

about 3,000 feet and scan Iraqi positions. Then, diving at about 200 mph, he

would yank back on the stick and drop a bomb from six to 10 feet over the

target — too close to miss. Seven seconds later, just as Evans made it to a

safe distance, the bomb would obliterate the target and rattle his teeth. This

method so terrified the Iraqis that they took to their heels without bothering

to fire at the plunging Gordon.

Although Rashid Ali’s

troops kept shelling Habbaniya, they balked at storming the base. Their

confidence was further undermined by the arrival of four Blenheim Mk.IVF

fighters from No. 203 Squadron on May 3. Eight of No. 37 Squadron’s Wellingtons

bombed buildings and strafed aircraft at Rashid on May 4 but lost a plane to a

combination of 20mm groundfire and an Iraqi Gladiator of No. 4 Squadron. The

Wellington crew was taken prisoner. Two Blenheim Mk.IVFs from Habbaniya also

strafed Iraqi aircraft at Rashid and Baghdad airfields. At that same time, six

Vickers Valentias and six Douglas DC-2s of No. 31 Squadron were flying troops

into Iraq and ferrying out civilian evacuees. One of the DC-2s flew into

Habbaniya with, among other supplies, ammunition for a couple of World War

I–era fieldpieces that for years had stood as ornaments outside the officers’

mess. To the garrison’s surprise the old guns proved still operable, and when

they opened up on the plateau, the Iraqis were convinced the British were being

reinforced with artillery. The trainers only flew 53 sorties that day, but they

also flew night missions to deprive their besiegers of sleep.

Still, the defenders

were suffering much worse than their foes seemed to realize. After four days of

combat, just four of the original 26 Oxfords were still battle-worthy. The

Audax, Gladiator and Gordon contingents were similarly depleted. Pilots were

also becoming even scarcer, as half-trained cadets died in action or suffered

from cracked nerves.

On May 6, an Audax

returned from a dawn reconnaissance mission with news that the Iraqis were

withdrawing. That encouraged Colonel O.L. Roberts of the 1st King’s Own Royals,

commander of ground forces at Habbaniya, to mount an assault, backed by the

Audaxes, to drive the enemy from the plateau. The timing was perfect — the

Iraqis, their morale broken at last, suddenly abandoned the heights in a

disorderly withdrawal down the Baghdad road toward Fallujah. Meanwhile, six

Wellingtons from No. 37 Squadron hit Rashid again.

That afternoon the

British spotted a column of Iraqi reinforcements approaching from Fallujah,

which soon ran into the forces retreating from Habbaniya. In complete disregard

for military procedure, both groups stopped on the highway, and personnel

jumped from their vehicles to confer, leaving all their trucks, tanks and

armored cars parked in plain view. At that point, Savile hurled every remaining

Audax, Gladiator, Gordon and Oxford he had — 40 aircraft — at the bunched-up

mass of vehicles. The young airmen in their old planes knew they would not have

a better — or another — chance like this, and they made the most of it with

all the shells and bombs they could carry. The two airstrikes took two hours,

with the British flying 139 separate sorties. One Audax was damaged by

groundfire, but they left the Iraqi convoy in flames.

Habbaniya also came

under Iraqi air attack, and two Gladiator pilots were wounded by bomb splinters

on the polo ground. One Gladiator intercepted a Douglas 8A and, after firing

two bursts, drove it off.

Armed ground personnel

and Arab auxiliaries ventured from the airfield and rounded up 408 demoralized

Iraqi prisoners, including 27 officers. Counting those POWs, Rashid Ali lost

more than 1,000 men that day, compared with seven British killed and 10

wounded.

The next day the

British could find no trace of the enemy near Habbaniya. A lone Nisr attacked

at 10:45 a.m., but a Blenheim Mk.IVF of No. 203 Squadron shot it down in

flames. The British also raided the airfield at Baquba, during which Pilot

Officer J. Watson, piloting a Gladiator, encountered an Iraqi Gladiator, attacked

it from behind and last saw it in a steep dive. Back at Habbaniya, ground

personnel eventually found and shot up a few Iraqi machine gun nests in the

village of Dhibban just east of the airfield.

In the previous five

blazing days, Habbaniya’s makeshift air force had flown 647 recorded sorties,

dropped more than 3,000 bombs of various sizes, totaling over 50 tons, and

fired more than 116,000 machine gun rounds. The British lost just 13 airmen

killed, 21 critically wounded and four to emotional collapse. It was a smashing

victory over Rashid Ali, who now faced the British reprisal with a demoralized

army and an air force that barely existed.

On the day that this motley fleet of RAF antiques was reducing the combined Iraqi forces outside Habbaniya to junk, Luftwaffe Colonel Werner Junck was in Berlin being briefed by Chief of Air Force General Staff Hans Jeschonnek. The colonel’s new mission was to organize a special force called Sonderkommando Junck, to be sent to Iraq. When Jeschonnek stated, “The Führer desires a heroic gesture,” Junck asked precisely what that meant. Jeschonnek replied, “An operation which would have significant effect, leading perhaps to an Arab rising, in order to start a jihad, or holy war, against the British.” The Germans were unaware that their erstwhile Mideast allies had already been soundly defeated and that Habbaniya’s garrison was at almost that very moment receiving a message from Churchill: “Your vigorous and splendid action has largely restored the situation. We are watching the grand fight you are making. All possible aid will be sent.”

Twelve Messerschmitt

Me-110Cs of the 4th Staffel (squadron) of Zerstörergeschwader

(destroyer wing) 76 (4/ZG.76), two Me-110Cs of ZG.26, seven Heinkel He-111Hs of

4th Staffel, Kampfgeschwader (bomber wing) 4, and a transport

contingent of 20 Junkers Ju-52/3ms and a few Ju-90s were hastily decorated in

Iraqi markings. They began flying to Mosul via Greece and Syria on May 11. In

an ill-fated start, one He-111 was fired on by Arab tribesmen as it approached

Baghdad airport. That plane landed with Major Axel von Blomberg, the Luftwaffe

liaison officer to Rashid Ali, dead.

On May 12 British

reconnaissance planes discovered several German aircraft in Iraq, and on the

14th one of No. 203 Squadron’s Blenheims spotted a Ju-90 at Palmyra airport in

Syria, confirming Vichy French cooperation in violation of its nominal

neutrality. British aircraft — including Curtiss Tomahawks of No. 250

Squadron, in the first combat sorties ever flown by P-40s — attacked Palmyra

the same day. It was the first round of hostilities that would ultimately lead

to the British invasion of Syria in June.

Habbaniya struck at

the Luftwaffe first when Flying Officer E.C. Lane-Sansom, of No. 203

Squadron, strafed Mosul at 3:15 a.m on May 16. At 9:35 a.m. three He-111s

bombed Habbaniya and were themselves attacked by a Gladiator. Caught in the

German gunners’ crossfire, Flying Officer Gerald D.F. Herrtage’s fuel tank was

hit, and though he bailed out before his Gladiator exploded in flames, his

parachute became tangled. Herrtage’s death was not in vain, however — one

Heinkel’s engine was disabled, resulting in a crash-landing before it reached

Mosul. The Germans launched no further bombing attacks, though that one had

done more damage to Habbaniya than all the previous Iraqi airstrikes combined.

On May 17, Habbaniya

was reinforced by the arrival of four more Gladiators of No. 94 Squadron and

four modified, extra-long-range Hawker Hurricane IIC cannon-equipped fighters.

While flying their No. 94 Squadron Gladiators over Rashid at 7:55 that morning,

Sergeants William H. Dunwoodie and E.B. Smith attacked the two ZG.26 Me-110s

just as they were taking off. Smith’s quarry crash-landed southeast of the air

base with both engines on fire, while Bill Dunwoodie’s disintegrated in a fiery

midair explosion.

Habforce finally

reached Habbaniya on May 18. The base was no longer threatened, but Smart had

suffered a nervous breakdown, and by some reports also been injured in a motor

vehicle mishap. He was sedated, loaded onto a DC-2 with women and children

evacuees and flown to Basra. Smart’s emotional collapse was hardly surprising

— he was primarily a school administrator, not a soldier — yet until

Churchill’s tardy response, every military officer above him had avoided taking

any responsibility for whatever happened at Habbaniya. Air Vice Marshal John

Henry D’Albiac took over command of the RAF in Iraq. Besides attacking the

Germans at Mosul, 200 miles away, Habbaniya’s aircraft helped British forces at

Fallujah fight off a succession of Iraqi attempts to retake that town.

On May 20 Habbaniya’s

Gladiators and Hurricanes dueled with four ZG.76 Me-110s over Fallujah.

Sergeant Smith was jumped by five Me-110s and narrowly escaped, but his

Gladiator was sufficiently damaged for the Germans to credit it to future night

fighter ace Lieutenant Martin Drewes, as his first of an eventual 52 victories.

The fighting for Fallujah reached its peak on the 22nd, when the Iraqis, backed

by light tanks, made a determined effort that resulted in heavy casualties to

both sides. Habbaniya’s planes flew 56 sorties in support of the British,

attacking a column of 40 vehicles moving up to reinforce the Iraqis, but losing

one Audax to return fire. Removing the Lewis machine gun from its rear

mounting, Flying Officer L.I. Dremas — a Greek pilot-in-exile — and his

gunner fought a running gun battle with the Iraqis until, aided by local

levies, they reached British lines.

Another Gladiator was

brought down by groundfire on May 23, but again the pilot evaded capture and

reached friendly lines. Meanwhile the Italians, after delays and only grudging

help from the Vichy French, finally flew 11 Fiat C.R.42 biplane fighters of the

155th Squadriglia (squadron) to Rhodes, reaching Kirkuk on May 26. From

there they began strafing British troops, who by then were marching from

Fallujah toward Baghdad. As Habbaniya-based planes were supporting the British

advance on May 29, they were attacked by two Fiats, which forced an Audax to

land damaged, with its pilot wounded. Wing Commander W.T.F. “Freddie”

Wightman of No. 94 Squadron dived on one of the C.R.42s and shot it down, with

the pilot, a 2nd Lt. Valentini, bailing out and taken prisoner.

On May 30, Habforce,

now numbering 1,200 men with eight guns and a few RAF armored cars, lay just

outside Baghdad, facing an Iraqi division. The RAF’s now-undisputed control of

the air made a great difference, however. The Iraqis refused to engage the

dreaded British, and the RAF took over Baghdad’s airfield. Realizing that the

game was up, Rashid Ali fled the capital after embezzling his soldiers’ monthly

payroll of 17,000 dinars. His followers followed suit, and Iraq’s pro-British

royal government was restored soon thereafter.

The Italians, too,

were sufficiently forewarned to depart Kirkuk for Syria on the 31st, burning

two Fiats that were too damaged to fly out. Sonderkommando Junck had a

more ignominious departure, the last of its surviving personnel escaping

overland to Syria on June 10, leaving behind the wrecks of all 14 Me-110s, five

He-111s and two transport planes. Those losses were far less damaging than the

pounding their prestige had taken in the eyes of the Arabs they had hoped to

convert to the Axis side. A quick, sizable German incursion in support of

Rashid Ali would have likely succeeded, but Adolf Hitler was too preoccupied

with the looming invasion of the Soviet Union to pay much attention to events

in obscure Iraq.

The implications of

the Habbaniya battle are staggering. But even the folks back in Mother England,

distracted by the capture of German Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, took

little notice at the time. Nonetheless, history has an obligation to give full

credit to the handful of pilots of No. 4 SFTS, who in five days had secured

Britain’s vital oil supply, as well as denied Nazi Germany a foothold in the

Middle East.

For further reading,

try: Dust Clouds in the Middle East, by Christopher Shores; Hidden

Victory, by Air Vice Marshal A.G. Dudgeon; and Gloster Gladiator Aces,

by Andrew Thomas.

This article was written by Kelly Bell and originally published in the May 2004 issue of Aviation History.