Tiberius was sent to the Balkans where trouble had broken

out again, encouraged by the news of Agrippa’s death. His brother Drusus went

back to Gaul, and for the next three years both would campaign aggressively on

these frontiers. It was clearly part of a concerted plan, although modern

claims that Augustus was striving to create defensible boundaries based on the

Danube and ultimately the Elbe do not convince. After years of tidying up the

existing provinces, completing the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula and most

recently occupying the Alps, Imperator Caesar Augustus was determined on

large-scale conquests in Europe. This was clean glory, winning the victories

that would fulfil the promise of peace through strength celebrated in the Ara

Pacis and justify his supervision of the provinces facing military problems. It

was also a chance for Tiberius and Drusus to add to their reputations and win

further experience of high command.

These aggressive campaigns were premeditated, and in the

last few years troops and supplies had gathered on the Rhine and in the Balkans

to undertake them. That is not to say that they were unprovoked, and modern

cynicism over claims that almost every Roman war was fought in response to

earlier raids is unnecessary. Raiding was common and often serious, but the

Roman response to it was less predictable, varying from minor reprisals to

heavy attacks or outright conquest. The coincidence of available resources and

a commander with the freedom of action and the desire to win glory determined

the scale and type of Roman response. These factors and the opportunity offered

by the migration of the Helvetii in 58 BC had led to Julius Caesar’s conquest

of Gaul, rather than the Balkan war he had expected to wage.

Untroubled by serious warfare elsewhere, and with a freedom

of action unmatched by any Roman leader in the past, Augustus decided to add to

Roman territory in both these areas. Like any Roman, he did not think so much

in terms of physical as political geography, seeing the world as a network of

peoples and states. It was these he would attack, and ‘spare the conquered and

overcome the proud in war’. Some would be added to the provinces while others

would simply be forced to acknowledge Roman power. The Greeks and Romans had

only a vague sense of the lands far from the Mediterranean, and certainly did

not appreciate the sheer size of central Europe and the steppes beyond. It is

quite possible that Augustus believed that he could conquer all of Europe as

far as the ocean that was believed to encircle all three known continents, but

such possibilities were for the future. At the moment his ambitions were more

restrained. He would add to Rome’s imperium, punishing the peoples who had

attacked the provinces in the past and preventing them from doing this in the

future.

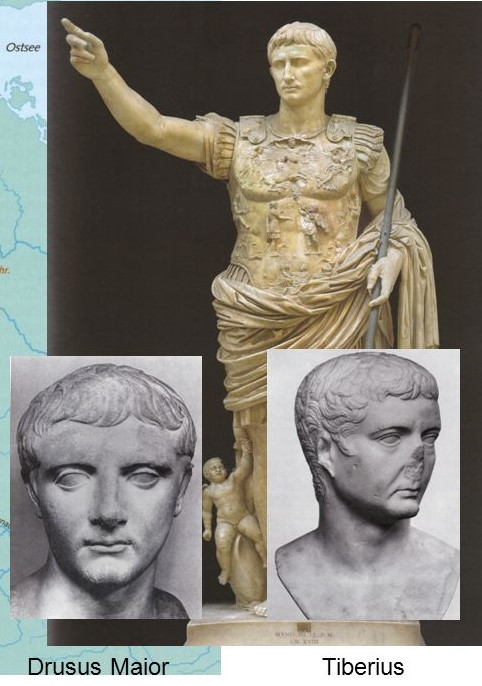

Tiberius and Drusus would lead the legions in person, while

Imperator Caesar Augustus supervised from a distance. In a change from the

recent pattern of long tours of the provinces, over the next years he made

short trips to be near the theatres of operations, stationing himself in

Aquileia in northern Italy on the border with Illyricum or at Lugdunum in Gaul.

Neither were so very far from Rome, and he returned to the City on several

occasions, usually after the campaigning season was over. Suetonius provides a

glimpse of these trips in an extract of a letter handwritten by Augustus

himself, telling his older stepson about the five-day festival celebrated

between 20 and 25 March in honour of the goddess Minerva:

We spent the Quinquatria very merrily, my dear Tiberius,

for we played all day long and kept the gaming board warm. Your brother made a

great outcry about his luck, but after all did not come out so far behind in

the long run; for after losing heavily he unexpectedly and little by little got

back a good deal. For my part, I lost 20,000 sesterces, but because I was

extravagantly generous in my play, as usual. If I had demanded of everyone the

stakes which I let go, or had kept all that I gave away, I should have won

fully 50,000. But I like that better, for my generosity will exalt me to

immortal glory.

The informal style is typical of surviving letters to family

and friends, and at least openly Augustus got on well with his stepsons. Drusus

was famous for his charm and affability, and had quickly become a popular

favourite. Tiberius was a reserved and complex character, easier to respect

than to like, but the fragments of letters written to him contain repeated

statements of affection and a gentle, bantering tone and heavy use of irony,

such as the talk of ‘immortal glory’. In another he describes a dinner where he

and his guests ‘gambled like old men’. There are many echoes of Cicero’s

letters in Augustus’ correspondence, in the repeated statements of affection,

the frequent quotations and jokes and perhaps also in false claims of deep

affection. Even so, at this stage there is no hint that the relationship

between the princeps and the man soon to become his son-in-law were anything

other than cordial.

Early in 12 BC Drusus completed a formal census in the three

Gauls, no doubt helping to organise the provinces, recording property and the

taxation due to Rome, and ensuring that they would give him plentiful supplies

for the forthcoming campaigns. The process had perhaps begun before Augustus

left the provinces the previous year, and the princeps had personally

supervised the first such census held in the region in 27 BC. Perhaps it was

also intended to be fairer than the existing system of levies which had been so

recently exploited by Licinus. Apart from Luke’s Gospel, we have no other

evidence claiming that at some point Augustus issued a single decree to hold a

census in, and arrange the taxation due from, the entire empire. It is

perfectly possible that there actually was such a single decree, effectively

making clear what already happened in an ad hoc way, and that this – like so

many other details – is simply not mentioned in our other sources. On the other

hand, the Gospel writer may merely reflect the perspective of a provincial, for

whom census and taxation were imposed by the Roman authorities with a

regularity that must have seemed as if it was a system imposed by a single

decision.

Sometimes the holding of a census provoked resentment and

even rebellion, especially in recently settled provinces – the prospect of

paying tax is rarely a pleasant one, especially if it went to an occupying

power. Livy claims that there was some trouble in Gaul in response to the

census, and Dio hints that this was the case, but gives no details, and if

there were disturbances then they were probably small-scale. There were

advantages to individuals and communities in registering property and rights,

since these were recorded in a form that had unimpeachable legal authority.

Most areas quickly became used to the process, and Drusus efficiently

suppressed whatever resistance did occur.

As well as organising the finances of the Gallic provinces

and keeping order, there was considerable activity preparing for the

forthcoming advance across the Rhine. A series of large military bases were

established to accommodate the troops mustering for the planned war. Numbers

are difficult to establish, but probably at least eight legions were gathered,

supported by substantial numbers of auxiliary troops and some naval squadrons

manning both small war galleys and transport ships. One of the bases was at

modern-day Nijmegen on the River Waal, and excavations suggest that it was

constructed somewhere between 19 and 16 BC. Some forty-two hectares in size,

and built of earth, turf and timber, it probably housed two complete legions as

well as auxiliary units. Like most of the other forts built by the army in

these years, whether on or to the east of the Rhine and in Spain, it does not

quite conform to the neat, playing-card shape so familiar for Roman army bases

in the first and second centuries AD. Augustus’ legions exploited good natural

positions and often sited forts on high ground, the ramparts roughly following

the contours to produce six-, seven- or eight-sided shapes. Their internal

layouts also vary, as does the design of individual building types, but in each

case the variation is less marked than the very close similarities. If it lacks

the greater uniformity of practice of the next century, it suggests the ongoing

development of such regular planning, evolving from traditional methods. Many

of the regulations for the army were set down by Augustus and would remain in

force for over a century without significant change.

Used to seeing the big stone forts of later years, it is all

too easy for us to accept without remark the scale and organisation of these

camps. Nijmegen was occupied for less than a decade, perhaps only for a few

years, and yet for that time the soldiers lived in well-built, neatly ordered

barrack blocks constructed to a standard design, with a pair of rooms for each

tent group (or contubernium) of eight men. Some of the excavated barrack blocks

are a little smaller and have been identified as auxiliary rather than

legionary, but even these offered considerable comfort for men living through a

north European winter. Far more generous are the headquarters building and the

substantial houses built for the senator serving as legate in charge of a

legion – or perhaps in such camps one man in charge of both legions – and for

the equestrian and senatorial tribunes. All of these buildings are matched by

similar structures in other forts built during these campaigns. In size and

organisation, such army bases resembled well-ordered Mediterranean-style cities

springing up on the fringes of the empire.

The winter months of 13–12 BC saw another raid by German

warriors into the Roman provinces, but this was repulsed by Drusus. In the

spring he launched the first of a series of attacks against the tribes living

east of the Rhine. Some of the army advanced using land routes following the

valleys feeding into the Rhine, while another part embarked on board ships and

sailed around the North Sea to make landings on the coast. At one point he

seriously misjudged local conditions, leaving many of his vessels aground when

the tide went out further than he expected. Julius Caesar had similarly

underestimated the power and tidal range of the sea during his British

expeditions. Fortunately the Frisii, a recently acquired local ally, arrived to

protect and assist the stranded Romans. Yet on the whole the story was one of

success. Tribal homelands were attacked, villages and farms burnt, animals

rounded up and crops destroyed, and any warriors who gathered defeated in

battle. A century or so later Tacitus would make a barbarian leader grimly joke

that the Romans ‘create a desolation and call it peace’. Faced with such

displays of the price paid for resisting Rome, several tribes joined the Frisii

in seeking alliance. Tiberius employed similar methods with similar success in

Pannonia.

Drusus returned to Rome at the end of the year for a brief

visit which demonstrated how many of the old restrictions on provincial

governors simply did not apply to those close to the princeps. He was elected

praetor, given the prestigious post of urban praetor, but tarried for only a

short time before hurrying back to the Rhine frontier to continue the war. Now

aged twenty-seven, at the start of spring 11 BC the princeps’ stepson attacked

again, this time leading one of the columns making its way overland. Some of

the tribes which had briefly capitulated may have decided to risk war once

more. Florus tells a story of the Sugambri, Cherusci and Suebi seizing and

crucifying twenty centurions who were in their territory, and this episode may

date to that year. The most likely reason for their presence would have been

either diplomatic activity as Roman representatives or more likely raising

recruits promised by treaty for service in the auxiliary cohorts. However, as

so often the Romans benefited from rivalries and disunity among the tribes. The

Sugambri mustered an army and attacked the neighbouring Chatti because they

refused to join them in alliance against Rome. While the warriors were occupied

in this way, Drusus struck quickly, devastating their homeland.

Such incidents are a valuable reminder that the area east of

the Rhine was populated by many distinct and often mutually hostile

communities. The Romans called them Germans, but it is unlikely that any of the

inhabitants of the region thought of themselves in that way. Julius Caesar

portrayed the Germans and the Gauls as clearly distinct, although even he admitted

that there was some blurring with the Germanic peoples already settled in Gaul.

The distinction was useful to him, since it helped to establish the Germans as

a threat to Gaul, and also made it easier for him to stop his conquests at the

Rhine. He and other ancient authors paint a gloomy picture of Germany and its

peoples, making them more primitive and at the same time more ferocious than

the inhabitants of Gaul. For them Germany was a land of bogs and thick forests,

with few clear tracks, no substantial towns, no temples and a population that

was semi-nomadic, who kept animals and hunted in the forests but did not farm.

Many old stereotypes of barbarism, stretching back to Homer’s portrait of the

monstrous Cyclops in the Odyssey, fed this impression of peoples who were

utterly uncivilised, and thus unpredictable and dangerous.

The archaeological evidence challenges much of this, while

presenting problems and complexities of its own. Before Julius Caesar arrived

in Gaul, a wide area of central Germany closely resembled the lands west of the

Rhine, boasting large hilltop towns with similar signs of industry, trade and

organisation as the Gaulish oppida. There was much contact between these areas,

and whatever the political relationship the cultural similarities are striking,

both belonging to what archaeologists call La Tène culture. During the first

half of the first century BC, these towns in central Germany are all either

abandoned or shrink dramatically in size and sophistication. In at least one case

there is evidence for violent and bloody destruction of the town, and in

general weaponry becomes far more common in the archaeological record. The

destruction was not wrought by the Romans, who had yet to reach these lands,

although it is possible that a contributing factor was the ripple effect caused

by the impact of Rome’s empire, whether through the shifting trade patterns or

direct military action. It is unlikely that the Romans were ever aware of what

was happening so far from their empire; they naturally assumed that the

situation they encountered when they did reach the area was normal, and that

the local peoples had always behaved in this way.

These German towns and the societies based around them had

probably already collapsed before Julius Caesar arrived in Gaul. How this

happened is impossible to know, and the evidence could equally be interpreted

as internal upheaval causing destructive power struggles, or as the arrival of

new, aggressive peoples. Migrations are often difficult to trace archaeologically,

but the repeated talk in our sources of large groups moving in search of new

land must at least in part reflect reality. Tribal and other groupings also

frequently defy the best attempts to see them in the archaeological evidence,

and are likely to have been complex, with recently formed and short-lived

groups mingling with older ties of kinship. Linguistic analysis of surviving

names based on later Celtic and Germanic languages does suggest real

distinctions at the time, but still does not make it easy to establish the

ethnic and cultural identity of particular peoples. There is a fair chance that

the Romans did not fully understand the relationships between named groups like

the Sugambri, Cherusci, Chatti, Chauci or Suebi, and it is more than likely

that these changed fairly rapidly as leaders rose and fell.

At the higher levels of society, there was certainly enough

instability and rapid change to justify some of the Romans’ view of a

population constantly on the move. Lower down this was less true. The towns had

gone, but in most areas east of the Rhine farms, hamlets and small villages

remained in occupation for long periods of time, spanning several generations.

The overall population was probably large, even if there were no big settlements.

Agriculture was widespread, albeit geared mainly to feeding the local

population and producing no more surplus than was needed to cushion them

against bad harvests. In the longer term the social and political structures of

the tribes were in a state of flux, and substantial populations periodically on

the move, but even so for decades at a time some tribal groups were settled on

the same lands, and had clearly acknowledged leaders. The Romans could try to

identify the tribes and know where their current homelands and chieftains were,

at least in the immediate future.

No doubt they misunderstood a good deal and made mistakes,

but Drusus and his staff steadily added to their knowledge of the peoples they

were fighting. The absence of good roads made movement of men and supplies

difficult for them. The lack of large communities meant that it was hard to

find large stores of food and fodder. In Gaul, Julius Caesar had frequently

gone to one of the oppida and either demanded or taken the supplies needed by his

army. It was far more difficult to go to hundreds of little settlements for

such needs, and so in Germany the legions were forced to carry almost all that

they needed. Where necessary, they built bridges over rivers and causeways

through marshes and this inevitably took time. In most cases Drusus and his men

followed the lines of rivers since this made it easier to carry some supplies

by barge, and the difficulty of moving overland helps to explain the reliance

upon sailing around the North Sea coast.

In spite of such difficulties the second season of

campaigning was successful, with the Roman columns penetrating deeper than ever

before into Germany before running short of supplies. With summer drawing to a

close, Drusus led his men back towards the Rhine – at this stage it would have

been difficult to feed and impossible to support any garrison left deep in

hostile territory over the winter months. German chieftains maintained bands of

warriors who had no other job apart from fighting, but these were few in

number. The army of a whole tribe or an alliance of tribes relied for numbers

on every free tribesman able to equip himself with weapons and willing to

fight, and inevitably it took a long time for such an army to muster. This

meant that a Roman army was far more likely to encounter serious resistance

when it retreated rather than in the initial attack. In this particular case

men had also returned from the raid on the Chatti and joined the bands

gathering to fight the enemy who had ravaged their lands. The Roman column was

large and cumbersome with its supply train, and thus its route was predictable.

The warriors were angry and they were confident, since a retreat on the part of

the invader inevitably seemed like nervous flight.

Drusus’ column marched into a succession of ambushes. The

Romans steadily fought their way onwards, but even when they repulsed the

attackers they were in no position to pursue them and inflict serious losses,

and could not afford the time to halt and manoeuvre against this elusive enemy.

Each success, however small, encouraged the warriors, and no doubt inspired

more to join them. This culminated in a much larger-scale ambush, which bottled

up the Roman column in a restrictive defile. The Romans were trapped and risked

annihilation, but then the essential clumsiness of a tribal army saved them.

German warriors did not carry enough food for a long campaign and thus wanted

the fight to be over quickly so they could return home. There was no single

leader able to control the army, but lots of chiefs with varying amounts of

influence, while each warrior reserved the right to decide when and how he

would fight. The Romans seemed to be at their mercy and so, instead of waiting

and letting them starve or fight at a disadvantage, bands of Germans massed

together and surged forward to wipe out the enemy and enjoy the plunder to be

taken from their baggage train. Close combat of this sort played to the

strengths of the legionaries, giving Drusus and his men the opportunity to

strike at their opponents at last. Turning at bay, the Romans savaged the

exultant warriors, whose over-confidence quickly turned to panicked flight.

Drusus and his men marched the rest of the way back to the Rhine unimpeded.

The campaign was declared a victory, as was the one waged by

Tiberius near the Danube. Augustus was awarded a triumph, which as usual he

chose not to celebrate, and his stepsons were granted the lesser honour of an

ovation combined with the symbols of a triumph (ornamenta triumphalia). In the

autumn both men returned to Rome, as did Augustus himself, and 400 sesterces

were given to each male citizen in the City to celebrate the success of Livia’s

sons. His fifty-second birthday was marked by a series of beast fights and

around this time Julia and Tiberius were married. Yet the news was not all

good. Octavia died suddenly, and so the ashes of yet another family member were

installed in the Mausoleum. The princeps’ sister received the honour of a state

funeral, with the principal oration delivered by her son-in-law Drusus.

In spite of this personal loss the mood was confident, and

the Senate decreed the closing of the doors on the Temple of Janus to signify

the establishment of peace throughout the Roman world. News of a Dacian raid

across the Danube prevented the rite from being performed, and in 10 BC the

wars were resumed. Augustus and Livia accompanied Drusus and his family to

Lugdunum in Gaul, where later in the year Antonia gave birth to their second

son, the future emperor Claudius. This year most likely saw the dedication

there of a lavishly built and decorated precinct enclosing an altar to Rome and

Augustus. Tribal leaders were summoned from all over Gaul to attend the

ceremony and take part in the rituals that would from then on be repeated annually.

Julius Caesar had talked of regular meetings of all the tribes of Gaul, and it

is quite likely that this new cult was intended to fill the gap left by the

abolition of such potentially subversive gatherings.

Tiberius spent the year campaigning in the Balkans,

supported by at least one other army whose leader also received the insignia of

a triumph. Drusus fought in Germany, and the brothers regularly wrote to each

other, just as they did to Augustus and their mother. On one occasion Tiberius

showed such a letter to the princeps, in which his brother talked of their

combining to force Augustus to ‘restore liberty’. Suetonius tells the story as

the first sign of Tiberius’ hatred of his kindred, but there is no other

evidence for hostility between the brothers and every indication of deep

affection. Perhaps the incident was an accident or a later invention. Modern

scholars tend to assume that Drusus wanted the princeps to resign and the

Republican system to be revived, and like to portray both brothers as

aristocrats with highly traditional views of politics. Yet the phrase is vague,

and may have meant no more than a dislike of some of the people given office

and influence under Augustus, and a desire that these be replaced by better men

– including themselves. Drusus was certainly ambitious. Elsewhere Suetonius

tells us that he was desperate to win the spolia opima, even going so far as to

chase German kings around the battlefield in the hope of cornering them and

killing them in single combat. It is a great leap of the imagination to connect

this with the incident involving Crassus in 29 BC, rather than seeing it as the

eagerness of a young aristocrat to win one of the rarest and most prestigious

of all honours.

In January 9 BC Drusus became consul just over a week before

his twenty-ninth birthday, and it may be that his hunt for the spolia opima

came in this year, when as consul he fought under his own imperium and

auspices. This was the year when he took his army to the River Elbe; a story

soon circulated that he was there confronted with the apparition of a

larger-than-life woman who warned him not to advance any further and prophesied

that his life was almost at an end. It was late in the season, and Drusus

returned to his bases on the Rhine, but was now able to leave some garrisons in

Germany. In the course of the four campaigns the land between the Rhine and the

Elbe had been overrun, and most of the peoples there claimed to acknowledge

Roman rule. How permanent this would prove was not yet clear, but the

achievement was certainly considerable. Then, on the way back to winter in

Gaul, Drusus had a riding accident and badly injured his leg. The wound failed

to heal and in September the young general died.

Tiberius was soon at his brother’s side, having rushed to

join him in a journey that became famous for its speed. He arranged for the

body to be embalmed and carried back to Rome with great ceremony. The first to

bear it were tribunes and centurions from his legions. Later they passed this

duty on to the leading citizens of Roman colonies and towns. On many of the

stages Tiberius walked with the procession. The mourning was a genuine

reflection of Drusus’ popularity – Seneca later claimed the mood was almost

that of a triumph as they marked the passing of the dashing young hero. The

ceremonies culminated in a public funeral in Rome. Tiberius delivered a eulogy

to his brother from the Rostra outside the Temple of the Divine Julius in the

Forum. Augustus gave another – perhaps to an even bigger crowd – in the Circus

Flaminius and outside the pomerium, the formal boundary of a city. (He was in

mourning and this prevented him entering Rome and performing the rites required

to mark his latest victory.) Actors wore the funeral masks and insignia of

Drusus’ ancestors in the traditional way. These were augmented by those of the

ancestors of the Julii, even though Augustus had never adopted his stepson,

before the body was cremated and the ashes added to those in the Mausoleum –

association with the princeps clearly trumped the right to be commemorated as a

member of the dead man’s real family.