Rome’s strategy in dealing with the Pictish threat after

c.340 was essentially defensive and reactive. Retaliatory strikes deep into the

Highlands were no longer part of the plan. Instead, the prime objective was

maintenance of a static frontier supplemented by covert military operations

between the two walls and in the wild lands further north. In an effort to

maintain the integrity of Hadrian’s Wall the Romans were helped by Britons

living in the lands beyond. The native population of this region between the

Hadrianic line and the disused Antonine ramparts became a first line of

defence. Such an arrangement suited the economic constraints and political

uncertainties facing Rome at that time. It allowed a dwindling number of

imperial troops to be redeployed elsewhere. At the hub of the new defensive

network lay Hadrian’s Wall with its forts and crossing-points. Behind the great

barrier stretched an infrastructure of roads, forts and watchtowers providing

both an early warning system and a capability for rapid response. In theory at

least, this strategy of ‘defence in depth’ shielded the people of Britannia

from hostile attacks by Picts, Saxons, Irish and other predators. North of

Hadrian’s Wall the four outpost forts garrisoned in the third century were

still occupied at the dawn of the fourth. Although situated outside the

Empire’s boundary, none of the quartet lay more than twenty miles from the

Wall. Their garrisons supervised the natives of the intervallate zone, a

population whose status vis-à-vis the imperial authorities after 300 remains a

matter of debate. In this region four large amalgamations of Britons already

existed in the second century: the previously mentioned Damnonii, Votadini,

Selgovae and Novantae. Whether these groups owed their origin to Rome’s

onslaught in the first century or were formed in spite of it we are unable to

say. By c.300, they may have been in existence for two hundred years or more,

but how much longer they endured is unknown. Ptolemy’s map shows their

positions relative to one another and identifies their chief centres of power.

Although the map shows a snapshot of political geography as perceived by Roman

geographers in the second century, the distribution of peoples in the

intervallate region may have remained largely unchanged two hundred years

later.

On Ptolemy’s map we see the Novantae inhabiting the northern

shorelands of the Solway Firth, in territory corresponding to present-day

Dumfriesshire and Galloway. Although their lands were vulnerable to raids from

Ireland and the Hebridean seaways, their main centres of power were sited on

the western coast, in the vicinity of Loch Ryan and modern Stranraer. Here, the

long peninsula of the Rhinns of Galloway, marked on the map as Novantarum

Chersonesus, protrudes into the Irish Sea. The key settlements were Rerigonium (possibly

Innermessan) and Loucopibia (possibly Gatehouse of Fleet). Directly north, in

what is now the county of Ayrshire, lay territory associated with either the

Novantae or with a people called Damnonii (or Dumnonii). Damnonian lands

included the lower valley and estuary of the River Clyde, together with parts

of what later became the medieval earldom of Lennox. An important centre of

power in this area was the imposing mass of Dumbarton Rock, a volcanic ‘plug’

jutting into the Firth of Clyde and dominating the surrounding area. Traces of

elite occupation on the summit indicate that it was used by high-status Britons

as far back as pre-Roman times. Later, when local native leaders were

apparently co-operating with Rome, the great Rock may have guarded imperial

interests in the north-western seaways. Through the Damnonian heartlands ran

the western extremity of the Antonine Wall, its turf ramparts and abandoned

forts already falling into dereliction by c.300. Further east, in Stirlingshire

and Lothian, the redundant barrier meandered through the northern borderlands

of the Votadini, another of the four intervallate groupings. Votadinian

territory extended south of the Firth of Forth to the River Tweed and perhaps

even as far as Hadrian’s Wall. Its hub was evidently the Castle Rock at

Edinburgh, but other hilltop strongholds, such as a probable oppidum on

Traprain Law, were also used in Roman times. The northern borderlands of the

Votadini faced the Maeatae of Stirlingshire and the Picts of Fife. On the south-western

flank lay the Selgovae (‘Hunters’), another large amalgamation of peoples.

Selgovan territory included the central and upper vales of Tweed together with

vast tracts of uncharted forest. Unlike their neighbours, the Selgovan elites

of the third and fourth centuries were closely supervised by Rome. Within their

territory lay the last of the outpost forts: Bewcastle and Netherby in the

valleys north of Carlisle, and Risingham on the strategic Dere Street highway.

The nature of the relationship between the Empire and the

intervallate Britons in Late Roman times is difficult to ascertain. It may have

been sustained by regular payments from the imperial coffers to purchase the

continuing goodwill of the four groups described above. One theory imagines their

kings and chiefs as foederati, ‘federates’, of Rome, their domains constituting

a buffer-zone between Hadrian’s Wall and the northern barbarians. If these

Britons did indeed serve as allies of Rome, they would have been expected to

bear the brunt of raids on the imperial frontier. Thus, while nominally

independent, they may have pledged to protect Roman interests against the

Pictish menace. Nevertheless, to all but the most trusting Roman officials, the

intervallate Britons would have represented a potential threat. Keeping an eye

on them was arguably the main function of the exploratores, ‘scouts’, a class

of troops whom we can envisage patrolling beyond the outpost forts. These men

were perhaps similar to the colonial rangers of eighteenth-century North

America, using local knowledge to gather intelligence and launching punitive

raids on troublemakers. The outpost fort at Netherby became so closely

associated with these ‘special forces’ that it was known along the frontier as

Castra Exploratorum (‘Fort of the Scouts’). Operating alongside the

exploratores were the shadowy areani or arcani, members of a secret service

responsible for covert operations, whose agents spied on the Picts and other

barbarians. Historians sometimes regard them as a kind of ‘Roman CIA’ and the

analogy may be broadly accurate.

Little is known of the kings and chieftains who ruled the

intervallate Britons during the fourth century. Some appear to be named in

genealogical texts preserved in medieval Wales but possibly drawing data from

much older northern sources. The Welsh genealogies or ‘pedigrees’ show the

lineages of a number of North British kings who lived in the sixth and seventh

centuries. Each pedigree uses a sequence of patronyms (‘X son of Y son of Z’)

to extend a royal ancestry back to the Late Roman period and, in some cases, to

an even more remote time. Any hope of gleaning genuine fourth-century history

is hindered by the stark fact that the texts containing the pedigrees were

written no earlier than the ninth century. Most survive only in manuscripts of

the twelfth century or later and none can be shown to be original creations by

North Britons rather than by Welshmen. The pedigrees cannot therefore be

regarded as storehouses of reliable information, especially for any period

before the time of the historical North British kings. As repositories of

genealogical data relating to the fourth century their value is even more

limited. They require very careful handling if they are to be used at all.

Several pedigrees include figures whose chronological

contexts seem to coincide with the final phase of Roman rule in Britain. Cinhil

and Cluim, for instance, are two individuals listed as ancestors of a

ninth-century king who ruled on the Clyde. We cannot be certain that these two

are anything more than fictitious ‘ghosts’ inserted into the pedigree to give

it a longer and more impressive lineage. If they existed, they probably belong

to the second half of the fourth century and may have been members of the

Damnonian elite. Another example is Padarn, apparently a Votadinian, to whom

the genealogists gave the epithet or nickname Pesrut (‘Red Tunic’). Alongside

Cinhil and Cluim, Padarn Pesrut is often regarded as a Briton of the

intervallate zone in Late Roman times. It has been suggested that all three

sprang from Romanised or pro-Roman families, their names being seen as medieval

Welsh renderings of Quintilius, Clemens and Paternus. Upon this a more or less

plausible scenario of loyal native foederati defending the Empire’s northern frontier

has been constructed, with Padarn’s red tunic being interpreted as a Roman

military garment, a gift from an imperial official to a trusted ally. Such

theories are imaginative but need not be taken seriously. Regardless of whether

or not the later Welsh names derive from Latin-sounding originals, we have no

reason to believe that such naming was exclusive to the imperial authorities or

to foederati in their service. Many non-Romans, friends and foes of the Empire

alike, arguably bestowed Roman-sounding names on their children if it pleased

them to do so. A young North Briton bearing a name such as Quintilius or

Clemens was just as likely to develop anti-Roman sentiments as a compatriot who

bore a non-Latin name. Nor is there anything uniquely Roman about the colour of

Padarn’s tunic, which could have been obtained from any competent tailor whose

skills included the extraction of red dye from plants such as madder. There

were no doubt many red tunics among Rome’s friends in the lands north of

Hadrian’s Wall, but probably just as many blue or green ones. Indeed, it is

easy to imagine the nickname Pesrut being bestowed on any Pictish warrior in

the hostile country beyond the Firth of Forth who chose to wear a bright red

garment on military expeditions.

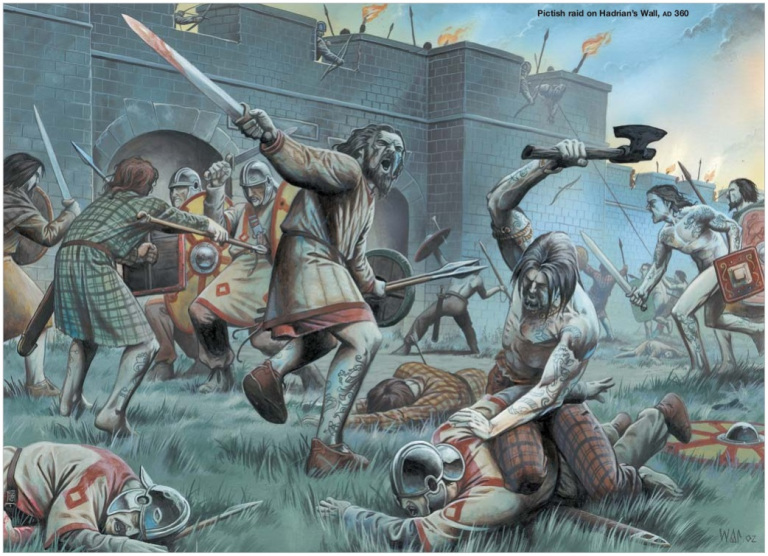

The Crisis of 367

The effectiveness of security arrangements on the northern

frontier was put to the test in the second half of the fourth century when

barbarian attacks increased. As well as the ever-hostile Picts the imperial

garrison also endured raids by Gaelic-speaking groups in the western seaways –

the Irish and the ‘Scots’. At this time the name Scotti seems to have been

borne by, or bestowed upon, any marauding band from Ireland or Argyll. Indeed,

it is likely that Roman observers regarded all the Gaels as one people. Like

the Picts, these raiders from the West had taunted Rome since the time of

Agricola. Three more groups now joined them: the Franks, whose descendants in

the following century would leave their mark on Roman Gaul by turning it into France;

the Saxons, who were soon to play a similarly important role in Britain; and a

mysterious people called Attacotti who were perhaps of Irish or Hebridean

origin. Eventually, the leaders of these hostile nations devised a barbarica

conspiratio, a ‘barbarian conspiracy’, to co-ordinate their attacks on Roman

Britain. Their plans came to fruition after crucial information was provided by

traitors on the Roman side: corrupt officials, army deserters and rogue agents

among the arcani. In 367, a huge barbarian assault was unleashed, its impact

sweeping away the imperial defences. Seaborne raids from east and west drove

far inland into the rich countryside of southern Britain, bringing death and

destruction to the bewildered citizens. Towns were ransacked and villas were

looted. Down from the north came the Picts, some to overwhelm the garrisons of

Hadrian’s Wall while others swarmed along the eastern coast in flotillas of

boats. The outpost forts north of the Wall were either bypassed or overwhelmed.

In a battle between the frontier army and Pictish marauders, Fullofaudes, the

senior Roman general in Britain, was taken prisoner. Leaderless and

demoralised, the entire imperial garrison was thrown into chaos. Some soldiers

cast off their uniforms and deserted their posts, while others roamed the land

in lawless gangs. Fearing the total loss of Britain, the emperor Valentinian

despatched a strike force of elite regiments led by the renowned Count

Theodosius. Two years of hard fighting eventually led to the expulsion of the

barbarians and, after Theodosius issued an amnesty for deserters, stability was

gradually restored. The soldiers returned to their forts and Hadrian’s Wall was

reinstated as the boundary of the Empire. In the wake of the crisis, however,

the outposts beyond the Wall were finally abandoned. Theodosius redeployed what

remained of their garrisons, disbanded the treacherous arcani and withdrew all

Roman forces behind the Tyne–Solway line.

After the disaster of 367, the Britons beyond Hadrian’s Wall

were effectively cut off from their countrymen south of it. Both groups had

suffered grievously during the barbarian onslaught, but there is no record of

Theodosius driving Pictish raiders from the lands of the Damnonii or Votadini.

The natives of the intervallate zone were presumably left to fend for

themselves. One medieval Welsh legend tells of a Votadinian prince or chieftain

called Cunedda who led a warband to North Wales to expel a colony of Irish

pirates from Gwynedd. Cunedda’s position in the genealogies makes him a figure

of the late fourth to mid-fifth century and this chronology has led some

historians to see him as a Roman federate transferred from Lothian during the

Theodosian reorganisation. Much detailed speculation about Rome’s relationship

with the Votadini has been woven around this scenario, but the data is too

fragile to support it. A more sceptical, more objective view sees the story of

Cunedda as a later Welsh attempt to create a fictional link between the kings

of Gwynedd and their fellow-Britons of the North.

Among the repercussions of the barbarian conspiracy the most

ominous development, at least for the native population of Roman Britain, was

the recruitment of Germanic foederati to guard the southern towns. These were

mostly Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians from the North Sea coastlands of what

are now Denmark and Germany. In northern Britain there were fewer towns and

villas than in the south, but one area where Romanisation had taken root was

the fertile Vale of York. There are archaeological hints that German warriors

were settled in this district in the late fourth century, either by Theodosius

after 367 or by the imperial usurper Magnus Maximus in 383. Serving Rome as

mercenaries, the Germans initially performed a useful gatekeeping role against

seaborne attacks by Pictish and Saxon pirates. Like all hirelings their

services were not given freely, but were bought with regular gifts of cash from

the imperial treasury. Any disruption to these payments was likely to turn

friendship and service to ill-feeling and hostility.

In the 370s, the lands south of Hadrian’s Wall returned to a

position of watchfulness. The northern frontier remained on a high state of

alert, as did the lines of forts and signal-towers along the western and eastern

coasts. North of the Wall the independent Britons, almost certainly without

Roman help, repelled marauding bands of Picts and regained control of their own

borders. But the barbarians were not so easily cowed and their raids continued

to gnaw Britannia from all sides. With the situation deteriorating once more,

the conspirators of 367 may have watched in gleeful disbelief as parts of the

imperial garrison began to leave the island in the period after 380. The first

big troop-withdrawal came in 383 when Magnus Maximus, a high-ranking officer in

Britain, resolved to make himself emperor. Ironically, he had previously

inflicted heavy defeats on the Picts and Scots, but now he poured his energies

into his personal ambitions. Supported and encouraged by other officers, he led

a substantial army across the sea to Gaul, thereby depleting Britain of forces

essential for her protection. The barbarians are likely to have taken full

advantage of his departure, but this time there was no Theodosius to confront

them. Troubles elsewhere in the Empire made it impossible to send

reinforcements to Britain. Another famous general, the half-Vandal Flavius

Stilicho, is depicted in a contemporary Latin poem leading an expedition

against the Picts at the end of the fourth century. It seems, however, that

this campaign existed only in the imagination of the poet Claudian who used it

as a literary device to illustrate the far-reaching extent of Stilicho’s fame.

In reality, the Empire lacked the will to rescue Britain from the brink of

catastrophe. To compound the situation, the Roman authorities now faced a peril

much closer to home.

On the last night of the year 405, the imperial frontier in

Germany was overwhelmed by a host of Vandals, Alans and other barbarians who

crossed the Rhine to begin the dismemberment of Roman Gaul. In Britain the

garrison reacted by rallying around Constantine, an ambitious officer with an

auspicious name, and proclaimed him emperor. Leading a large force, Constantine

sailed over to Gaul to assert his claim against forces loyal to the legitimate

emperor Honorius. The loyalists were victorious and the usurper was executed.

By 410, his henchmen in Britain were rooted out, but they bequeathed a

desperate situation. With the depleted imperial troops struggling to stand firm

against barbarian raids, the native elites of the southern towns seized control

of the imperial administration. Taking the initiative, these Romanised Britons

restored a semblance of order before appealing to the emperor for aid. But

Honorius was grappling with the problems of a disintegrating Empire and had no

help to offer to beleaguered subjects in a faraway land. Instead, he sent a

letter urging the anxious Britons to organise their own defence. This had

profound consequences for the remaining Roman troops, all of whom relied on

wages issued by the imperial treasury. Their pay had probably been arriving

erratically for some time, but now it ceased altogether. Without it the

soldiers had no incentive or obligation to defend the Empire. On the northern

frontier, groups of disillusioned men gradually abandoned their forts, taking

their families with them and vanishing into the countryside. In the lands to

the south, the last vestiges of imperial bureaucracy were swept away as power

was seized by native leaders. By c.420, the Roman occupation of Britain was

over.