Floating Batteries at the Capture of Kinburn.

Having driven Gorchakov’s army out of the south side of

Sevastopol the allied commanders were at a loss about what should be done next.

The battle had been expensive in soldiers’ lives, ammunition and resources; so

much so that it was difficult to avoid a general feeling that they had

justified their presence in the Crimea by taking the city whose capture had

eluded them for a year. This was particularly true in the French camp where

there were smiles and congratulations all round. Pélissier was given a marshal’s

baton and, much to the irritation of the British, was appointed a mushir, or

commander-in-chief, by the Sultan; Bruat was promoted to full admiral (but did

not live long to enjoy the pleasure as he died at sea two months later) and

Simpson was awarded the Légion d’Honneur. Even the much-reviled telegraph came

into its own on 12 September when Pélissier received the thanks of a grateful

emperor: ‘Honneur à vous! Honneur à votre brave armée! Faites à tous mes

sincères félicitations.’ (‘All honour to you. Honour to your brave army. I send

to you all my sincere congratulations.’)

At home in Paris there were sonorous celebrations allied to a sense of relief; a Te Deum was celebrated in Notre Dame, which had been decorated with the flags of the allied powers. Sevastopol had fallen and in many people’s minds the victory and the part played by Pélissier’s men symbolised a rebirth of French military might. For a few happy hours 1812 became just another dusty date in a long-forgotten history and it seemed possible that Sevastopol was but a springboard for even greater successes against the Russians. Two weeks after Sevastopol fell Colonel Rose, British liaison officer at French HQ, sent a thoughtful despatch to Clarendon which captured the mood in the French camp:

After 1815 the spirit of the French Army was lowered by a

succession of reverses. The successes in Algiers against Barbarians, without

artillery, were not sufficient to restore them the prestige they once enjoyed.

But the share of successes which the French Army have had

in conquering a Military European Power of the first order, in battles on the

field, and in the Siege of a peculiarly strong and invested Fortress, a Siege

without many parallels in History, have not only improved, very much, the

experiences and military qualifications of the Officers and men of the French

Army, but have raised their military feeling and confidence.

To capitalise on that effect Napoleon insisted that the war

must continue and that Russia must be humbled before there could be any peace

settlement. Not only would that process isolate Russia from Europe but it would

also restore France as a major power and destroy for ever the settlement of

1815. It might even be possible to realise Napoleon’s dream of rebuilding the

kingdom of Poland and placing his cousin on its throne.

There was much to recommend this way of thinking. France had

been left exhausted by the Napoleonic wars and the nation itself had been

humbled, its frontiers reduced to those of 1789. Napoleon III certainly

believed that he had a mission to restore his country’s fortunes by continuing

the war, but he was already swimming against a tide of growing disapproval with

the war. While his fellow countrymen had been happy and relieved to celebrate

the fall of Sevastopol it could not be denied that the victory had been won at

a cost. The casualties seemed to be disproportionate to any diplomatic or

strategic gain and the need to keep the forces supplied for another winter was

a strain on an already overloaded exchequer. France simply did not have the

resources to continue the war and was unable to match the expenditure lavished

on it by her British allies. London’s well-filled purse was one very good

reason why Napoleon was so desperate to keep the cross-Channel alliance in

being.

He had little difficulty in persuading his allies to be

assertive. Palmerston remained as bellicose as ever and, together with

Clarendon, warned colleagues that the war was far from being over and might

last another two or three years. Their message was clear and unwavering:

Britain’s war aims would not be altered and there could be no negotiated peace

until Russia had been defeated. To achieve that goal Palmerston still thought

that it would be possible to construct a grand European alliance similar to the

coalition which had defeated Napoleon forty years earlier. As he told Clarendon

on 9 October, ‘Russia has not yet been beat enough to make peace possible at

the present moment.’ Military pride was also at stake. Palmerston had refused

permission for the church bells to be rung in celebration of the recent victory

as it was all too evident that British troops had not distinguished themselves

in the fighting.

The Turks were keen to see the allies continue the war in

the Crimea as this would allow them to open operations in Asia Minor and to

that end they insisted that Omar Pasha be allowed to withdraw his army from the

Crimea. Russia, too, was adamant that the war was far from over. ‘Sevastopol is

not Moscow, the Crimea is not Russia,’ said Alexander II in a proclamation to

Gorchakov shortly after the fall of Sevastopol. ‘Two years after we set fire to

Moscow, our troops marched in the streets of Paris. We are still the same

Russians and God is still with us.’ In military terms the Russian commander had

merely made a tactical retreat into a new position which would continue to pose

problems to the allies. The tsar also guessed correctly that his enemies had no

intention of marching into Russia and that unless Gorchakov were defeated

stalemate had returned to the Crimean peninsula. Given that unassailable

position, the allies’ only hope of inflicting a decisive defeat seemed to lie

in the Baltic; Dundas’s destruction of Sveaborg having given rise to hopes that

a similar campaign in the spring of 1856 could crush Kronstadt and leave St

Petersburg open to attack by sea and land forces. It was an idea which would

exercise the minds of allied planners throughout the winter.

None the less, the continuing public bellicosity could not

disguise the fact that there was also a growing desire for peace, especially in

France, where Count Walewski, Drouyn de Lhuys’s replacement as foreign

secretary, was playing a somewhat different game. An illegitimate son of

Napoleon Bonaparte, he was considered by Cowley to be an intellectual

lightweight who was too close to the emperor’s pro-Russian half-brother, the

Duc de Morny, and therefore not to be trusted. To Clarendon he was a parvenu,

‘a low-minded strolling player’ whose ‘view of moral obligation’ was always

‘subservient to his interests or his vanity’. Palmerston shared that opinion

and added the thought that if anything were to happen to the emperor there

would be no shortage of French politicians of Walewski’s ilk who would be

prepared to sue for peace with the Russians.

There were grounds for these fears. Although Cowley and

Clarendon, the British statesmen most directly involved, never lost their

suspicions about those who served the emperor – based largely on social

snobbery, it must be admitted – they were right to pay close attention to the

new French foreign secretary, Walewski. At a time when the allies were

attempting to maintain a common front and continue the war he was in secret

negotiation with the Russians through the Duc de Morny and a shadowy figure

called Baron Hukeren, the adopted son of the Dutch ambassador in Paris, whom

Cowley described as ‘among the numerous speculating and political intriguers

that abound in the capital’. Initially, Napoleon seems not to have known that

covert peace feelers were being made but by October he had given them tacit

approval. These were conducted on two fronts: through his friendship with Prince

Gorchakov, the duke made it known that France was ready for peace while a

similar message was passed by Walewski to Nesselrode’s daughter who was married

to the Saxon ambassador in Paris, Baron von Seebach. At the same time the

Russian ambassador in Berlin, Baron Budberg, alerted the Prussian government

that the tsar was ready to reopen negotiations. While, in themselves, these

clandestine talks did not lead to the reopening of peace talks, they at least

helped to pave the way.

Meanwhile, as had happened earlier in the year when the

Vienna conference seemed to hold out the hope of a cessation of hostilities,

the British and French governments urged their commanders in the Crimea to

continue the campaign. Having told Simpson that from the Queen’s palace to

humblest cottage British hearts were beating with pride at ‘this long

looked-for success’, Panmure turned to sterner matters:

The consequences of this event upon the morale of the

Russian Army must be very great, and I trust that in concert with Marshal

Pélissier you have devised means to take advantage of them and to give the

enemy no rest till his overthrow is completed.

In order to keep this object properly in view you must

not suffer your mind to rest upon any expectation of peace; your duty as a General

is to keep your Army in the best condition for offence and to turn your

attention to all the means in your power for so doing.

There was considerable mortification that the victory had

not been followed up with a further attack on the Russian position and Panmure

told Simpson that there were to be no celebrations in the army until Russia had

been finally defeated. A succession of despatches from London attempted to goad

the British commander into action but without success. Simpson simply reiterated

his and the French belief that it would be folly to attack the Russian

positions and he remained unmoved by an unhelpful suggestion that he should

think of ‘applying a hot poker’ to make Pélissier do something positive. The

impasse was broken on 26 September when Panmure sent a peremptory telegram to

the British commander demanding action:

The public are getting impatient to know what the

Russians are about. The Government desire immediately to be informed whether

either you or Pélissier have taken any steps whatever to ascertain this, and

further they observe that nearly 3 weeks have elapsed in absolute idleness.

This cannot go on and in justice to yourself and your army you must prevent it.

Answer this on receipt.

From the evidence of the correspondence between the two men

it is difficult to know what Panmure wanted to achieve from this telegraphic

despatch. That he was anxious to hear Simpson play a more martial tune was

beyond doubt, yet the commander’s own letters betray a worrying timorousness

that was not to be cured by Panmure’s mixture of threats and cajoling. In one

letter he would chide Simpson for playing second fiddle to the French and

insist on action, ending the despatch with an order that the British soldiers

were not to be given spirits before going on sentry duty; in another he would

reflect on the pleasure of discussing the campaign at some future date over a

bottle of claret. However, his latest despatch had one obvious effect: the man

who had gone out to the Crimea with no other thought than to report on Raglan,

finally admitted that high command was too great a burden to bear. Two days

later Simpson telegraphed his resignation, explaining that he could not remain

in command while facing sustained criticism, and his offer to stand down was

quickly accepted.

As Codrington was the designated successor, it should have

been an easy matter to confirm his promotion, but during the final assault on

Sevastopol Codrington seemed to have lost his nerve – Newcastle was

particularly withering in his criticism – and renewed thought was given to the

command of the army in the Crimea. Once again the candidates’ claims were

examined and during the hiatus, which lasted three weeks, Panmure was forced to

address his orders simply to the British Headquarters in the Crimea. Despite

doubts about his abilities Codrington was confirmed in command on 15 October

but did not take over the office until a few weeks later: more than any other

attribute, his ability to speak fluent French and his easy social skills seem to

have counted in his favour. To soften the blow to the other commanders, on 10

December the army was divided into two corps, command of each going to Campbell

and Eyre.

By then the British Army was in a much better position than

in the previous year and relatively well equipped to face another winter. Each

soldier had been given a new hard weather uniform consisting of two woollen

jerseys, two pairs of woollen drawers, two pairs of woollen socks, two pairs of

long stockings, one cholera belt, one comforter, a pair of gloves, a fur cap,

greatcoat and waterproof cape. At Panmure’s insistence – he was a great

stickler for detail – each man was also given, and ordered to use, a tin of

Onion’s Drubbing, a new patented waterproof treatment for boots; and on 7 December

four hundred field stoves specially designed by Alexis Soyer arrived at

Balaklava. As an aid for observing the enemy in forward positions the army was

supplied with a thousand trench telescopes of the kind which would be used in

the First World War ‘for looking at objects without exposing the viewer’.

With better conditions, the supply problems having been

largely solved, the army’s morale improved. Before winter settled in there were

race meetings and hurriedly improvised shoots for the officers and theatricals

for the men. Despite Panmure’s exhortations about keeping drunkenness at bay

the independently owned canteens at Kadikoi did brisk business and, with the

Russians content to keep their distance, the miseries of the last winter’s

discomforts in the trenches were soon forgotten. By contrast it was now the

turn of the French to suffer. Cholera followed by typhus ran through their camp

and, added to a general air of disaffection, there were calls from the veterans

of the fighting to be sent home. As the casualties from illness began to mount

these demands were met: on 13 November Rose reported that the French Imperial

Guards regiments were to be withdrawn and that eight line infantry regiments

were to return to Algeria. Despite promises to the contrary, these were not to

be replaced.

Before the armies went into winter quarters at the beginning

of November, the British in good spirits, the French in as sorry as state as

their allies had been in the previous season, there were two noteworthy attacks

on the Russians. Having despatched part of their cavalry to Eupatoria, French

units led by General D’Alonville attacked a larger Russian force on 20 October

and succeeded in compelling it to withdraw with the loss of many casualties.

However, D’Alonville chose not to follow up the success, other than to continue

the harassment of Russian stragglers, because, according to Rose, the French

chief of staff, General de Martimprey, had ordered his subordinate commanders

to rein in any propensity for offensive activities:

I again perceived that he was opposed to any hostile

operation against the enemy on a large scale. But whether he entertains this

opinion because he thinks that the Enemy will leave the Crimea, without being

forced to do [sic], or because he is of the conviction, which he lately

expressed, that negotiations in the winter will bring about a peace, I know

not.

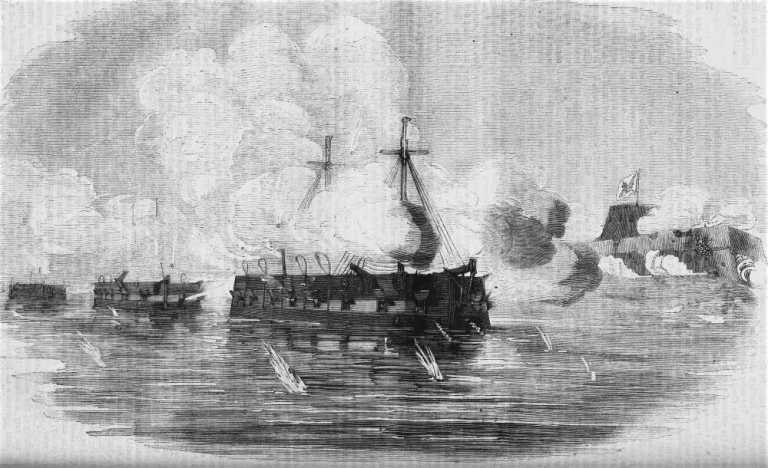

The other operation was far more aggressive and it was

destined to be the last blow struck by the allies during the war. It was also

the most successful, a combined forces’ attack on the Fort Kinburn, a heavily

defended Russian position which covered the confluence of the Rivers Bug and

Dnieper. The brainchild of Lyons, it made full use of three newly developed

French armoured steam batteries which, together with the allied gunboats and

battleships, battered the fortress into submission. The French played a full

role by committing 6000 men to the infantry force of 10,000, command of which

was awarded to General Bazaine, as well as three battleships and a number of

gunboats, although it remained unclear if Pélissier’s enthusiasm for the

assault was governed more by a succession of orders from Paris or by his newly

developed infatuation with Bazaine’s wife, Soledad. During Bazaine’s absence,

Pélissier’s coach, captured from the Russians, was to be seen each day outside

Soledad’s quarters. It was not the only romance thrown up by the war: Canrobert

had fallen for the daughter of Colonel Strangways, the British gunner commander

killed at Inkerman, but as with Pélissier’s fondness for Bazaine’s wife nothing

came of the wartime dalliance.

The attack on Kinburn, though, was a complete success. On 16

October the infantry and marine forces made an unopposed landing on the Kinburn

peninsula to cut off the fortress from reinforcements and to attack the

garrison should it decide to retire. The following day, having advanced under

cover of darkness, the allied fleet commenced a heavy bombardment, using

tactics similar to those employed at Sveaborg a month earlier. Having been

infiltrated into the bay in front of the fortress the gunboats and steam

batteries were able to produce a sustained bombardment which quickly silenced

the Russian guns. Then the allied battleships steamed into line to fire an

equally heavy succession of broadsides which left the garrison with no option

but to surrender. The way was open to strike inland but Bazaine called a halt

to the operation once the forts and Kinburn and Ochakov (on the other side of

the estuary) had surrendered. Following the destruction of Sveaborg, the

successful outcome of the Kinburn operation demonstrated that the allies now

had the naval capacity to attack and defeat Russia’s hitherto impregnable

sea-fortresses.

As winter set in other activities included a reconnaissance

of the Baider valley to ascertain whether or not an attack on the Russian

positions at Simpheropol would yield results. Napoleon thought so but the

French-led scouting party reported back that the Russians were entrenched on

the high ground and that any attack would only result in unacceptable

casualties. That fear lay at the heart of the allied command’s thinking. With

the fall of Sevastopol, France had recovered her honour and, just as

importantly, her right to sit at the high table when European matters were

being discussed. Pélissier did not want to pursue the war against the Russians

and by the middle of October he had come to the opinion that the allied army in

the Crimea should be reduced by almost half to 70,000 and that it should take

up defensive positions on the Chersonese peninsula.

His thinking chimed in with the mood at home where the war

was now decidedly unpopular. On 22 October Cowley reported a conversation with

the emperor in which Napoleon argued that the war had become an expensive

anachronism and that the presence of the allied armies would not encourage

Russia to negotiate. That could only be achieved by diplomatic means. As

evidence, he produced a report from Pélissier in which the marshal claimed that

there was nothing for the allies to conquer in southern Russia – ‘sterile

plains which the Russians will abandon after some battles in which they will

lose a few thousand men, a loss which causes them no decisive damage, whilst at

every step the Allies with a great sacrifice of men and money and with nothing

to gain will risk each day the destinies of Europe’.