Vandals

The boy Romulus Augustulus is commonly said to have been the

last Roman emperor in the West. He was deposed and superseded in AD 476 by a

German officer called Odoacer, who had served under various Roman commanders.

Odoacer was content to rule as king of Italy, recognizing the suzerainty of the

eastern emperor in Constantinople, and unconcerned to claim the traditional

imperial titles and honours for himself. Romulus, in any case, had been a

usurper, raised to power by his father’s coup d’ état, and he was not

recognized by the eastern emperor. However, the abandonment of the imperial

title has a symbolic significance and provides historians of ancient Rome with

a pretext for closing their account.

There is no obvious valedictory date for Roman history. Any

event identified as terminal must in reality be a symbolic ending. For

Graeco-Roman civilization did not collapse or explode. It was simply

transmuted, by a gradual process, out of recognition; in many ways its

institutions, assumptions and attitudes are still with us, having survived and

revived in disguised and undisguised forms during the passage of the centuries.

However, it is increasingly difficult, as time advances, for any history to be

a world history, and our sense of form decrees that every story should have a

beginning, middle and end. Apart from Romulus Augustulus, there are various

possible stopping places for the historian of ancient civilization.

In 395, the great if somewhat bigoted Christian Emperor

Theodosius died, bequeathing the Roman world to his two ineffectual sons

Arcadius and Honorius, the first of whom exercised imperial power in the East,

the second in the West: a situation which perpetuated discord between the two

halves of the Empire. The administrative distinction foreshadowed in

Diocletian’s arrangements gave political expression to the pre-existing

cultural and linguistic difference between the Greek East and the Latin West.

The difference has left its mark on ecclesiastical history. Perhaps, therefore,

we might assign “the end of the Roman Empire” to the point at which it ceased

to be a unity: ie, the death of Theodosius the Great.

On the other hand, the dignity and power of the Roman Empire

were astonishingly restored by the conquests of the inspired eastern Emperor

Justinian, who reigned as Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Justinianus, assuming the

title of “Augustus” at his coronation in 527. Justinian extended his authority

into Africa, Italy and Spain, where his armies prevailed against the Vandal and

Gothic invaders. He also maintained alternating war and diplomatic relations

with the Persians on his eastern frontier. Justinian’s services to the arts of

peace were also outstanding. He initiated many works of architecture and civil

engineering; his most magnificent achievement in this respect was, of course,

the building of Constantinople’s great cathedral Santa Sophia (“The Holy Wisdom”).

Justinian has also been immortalized by his contribution to the legal faculty.

His codification of Roman Law was at least as monumental a work as the building

of Santa Sophia. Unfortunately, his reign, like that of many Byzantine

emperors, was troubled by theological disputes which obsessed not only the

clergy but the population at large. As often in history, religious differences

provided rallying points for political ambitions and aspirations. In

Constantinople, opinions became war-cries, indicative of allegiance. If you

backed the green charioteer in the circus, you believed certain things about

the relationship of the Father to the Son and at the same time favoured one

branch of the imperial family rather than another. Allegiances, on analysis,

are always “package deals”, but Constantinople produced a reductio ad absurdum

of the incorrigible human tendency to faction.

After Justinian’s death in 565, his far-flung Empire soon

collapsed, and for a time Constantinople was well content only to defend its

own walls. But again, great emperors like Heraclius (610–641) and Leo the

Isaurian (717–740) saved civilization. The last of the western provinces to

survive was the “exarchate” of Ravenna. This finally fell to the Lombards

(Longobards), a Germanic people who had for long occupied the north Italian

territory which still bears their name. Perhaps the fall of Ravenna in 751 is

another suitable terminus for Roman history. It is, of course, equally possible

to propose a much earlier date, and as such, the sack of Rome by the Goths in

410 suggests itself. But this again must be regarded as a purely symbolic

event. Rome at this time was not even the capital of a prefecture or its

subdivision, a diocese, as the civil departments of Diocletian’s and Constantine’s

Empire had been termed. It was certainly not a city of any military

consequence. It was simply, as ancient Athens had long ago become, a venerated

tourist centre, almost a kind of museum.

The Eastern Front

Justinian was one of many emperors who would have been glad

to live on terms of peaceful coexistence with the Persians – even if he had to

pay for the privilege. But the Persians were not so minded. They well

understood the manpower difficulties of their old adversaries, and while the

eastern and western Empires were assailed by a multitude of barbarians on other

frontiers, the Sassanid rulers saw fit to take their opportunity.

Since the defeat of Valerian and the retribution exacted in

the name of Rome by Odenatus, the tide of war on the Euphrates frontier had

ebbed and flowed recurrently. Galerius, Diocletian’s faithful “Caesar”, had at

first suffered defeat (near Carrhae again) at the hands of the Persian king

Narses. However, he amply avenged the disaster, and in the following year (AD

298) Rome’s eastern frontier was pushed still farther eastward, across

Mesopotamia as far as the Tigris.

In the year 359, Shapur II, bent on restoring Persian

fortunes, led his armies into Mesopotamia and captured several Roman frontier

fortresses. Reacting to the eastern emergency, Constantius II was obliged to

recall troops from Gaul, and the resentful army there proclaimed Julian, his

“Caesar” on the western front, as “Augustus”. But frontier pressures being what

they were, before the imperial rivals could find leisure to fight each other,

Constantius died, and Julian was left as sole emperor to vindicate Roman power

and prestige in the East. He led his army along the Euphrates, assisted by

river transport, and at a point some 50 miles (80km) from Babylon, taking advantage

of an ancient canal, conveyed his ships across to the Tigris. Here, however,

instead of investing the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, he was lured into a

further eastern march, in which lengthening lines of communication produced

horrible privations for his troops. Even where the country was fertile, the

enemy had devastated it. The Persians harassed him as the Parthians had

harassed Roman armies in earlier times. In this campaign, Julian died of a

wound, and the Persians soon recovered Mesopotamia from the inadequate officer

whom his bereaved troops acclaimed as an imperial successor. Perhaps in this

long story of border warfare, the Romans – or at any rate their Byzantine

representatives – may he regarded as having the last word. For the Emperor Heraclius,

after a protracted series of campaigns, overcoming a formidable alliance

between the Persians and the barbarian Avars north of the Black Sea (626),

finally destroyed the army of the Persian king Khusru (Chosroes II) in a battle

near Nineveh.

The Persian Empire was by this time thoroughly weakened and

already confronted by other enemies than Rome. In 454, the Persians had to meet

an invasion of the White Huns, a branch of the Central Asiatic horde which

already menaced a great part of the Eurasian continent. Perhaps if the

Sassanids had not squandered their energies in futile wars with Rome for very

limited gains, they would have been better able to resist the Arabs who, early

in the seventh century, fired by the message of their Prophet, defied Persian Zoroastrianism

with a fanaticism greater than its own.

Yet while it is possible to regard the wars of Romans and

Persians as having a merely exhausting effect on both sides, these wars

provided a training ground and were the source of many military lessons. The

Romans conducted their frontier defence in the East with great sophistication,

and the small fortress garrisons of the Euphrates frontier on more than one

occasion showed their heroism. The Romans also learned much from Persian

methods of fighting. Chain-mailed and plate-armoured horsemen, at the time when

the Notitia Dignitatum was compiled, formed a regular part of the Roman army, a

development which had started with Trajan. There seems to have been even an

attempt to evolve a hybrid from the light mounted bowman and heavily armed

lancer. For we learn of armoured archers on horseback (equites sagittarii

clibanarii). There is, however, no record of their successful application in

action.

Hostile and Friendly Goths

Of all the barbarian peoples who penetrated the Roman Empire

in the later centuries of its history, the Goths made the deepest impression.

They were a Germanic people of Scandinavian origin, who had begun their

southward migration about the beginning of the Christian era. Evicted by

Claudius “Gothicus” in the third century AD, they again exerted pressure in the

fourth. Aurelian had allowed the West Goths (Visigoths) to settle north of the

Danube in what had previously been the Roman province of Dacia. The East Goths

(Ostrogoths), who had formed another group, had occupied the region of the

Ukraine.

At the end of the fourth century, the Goths were under heavy

pressure from the migratory movements of east European and Asiatic peoples, and

sought the right to settle within Roman territory. The Roman Emperor Valens,

then occupied in war against Persia, strove to ensure, through his commanders

on the Balkan front, that the Goths should be disarmed before they were

admitted as settlers, but he was unable to enforce this precaution. The

unrelenting eastern pressures were driving successive waves of barbarian tribes

across the Danube and the Rhine, and Valens was eventually obliged to return

from the East in order to take command himself. In a violent battle near

Adrianople (378) he was defeated by the immigrants and killed. His body was

never recovered. Imperial prestige suffered badly. The Emperor’s cavalry had

fled and his infantry been annihilated.

Even after this great Roman disaster, however, the Goths did

not overrun the Empire. In the first place, they were unable to capture Roman

fortified points, lacking both the skill and the equipment requisite for

assault on fortifications. Secondly, the Romans were saved, as often in the

past, by a great general who rallied their armies when the situation seemed

desperate. The saviour on this occasion was Theodosius, a gifted officer raised

to the imperial power by the surviving “Augustus”, Flavius Gratianus (Gratian),

in order to cope with the emergency. Theodosius solved the manpower problem by

enrolling friendly Christian Goths, already settled within the Empire, to

resist the invaders. A treaty was at last made with the immigrants, according

to which they were allowed to settle within the Empire, south of the lower

Danube, as a confederate people under their own rulers, but serving under Roman

officers in time of war. This was very much what they had wanted in the first

place.

For Theodosius’ policy of absorbing the barbarians whom he

could not evict, there was an ample precedent. Such absorption was in the essence

of Roman political instinct; it can be instanced in the earliest days of the

Republic and in the later recognition of client kingdoms. Faced with

everlengthening numerical odds, caused not only by migratory pressure but also

by expanding barbarian populations, the Roman Emperor could hardly have done

better. It was indeed an imaginative solution. However, the point had been

reached when absorption of barbarians could more appropriately be described as

dilution of Romans among barbarians.

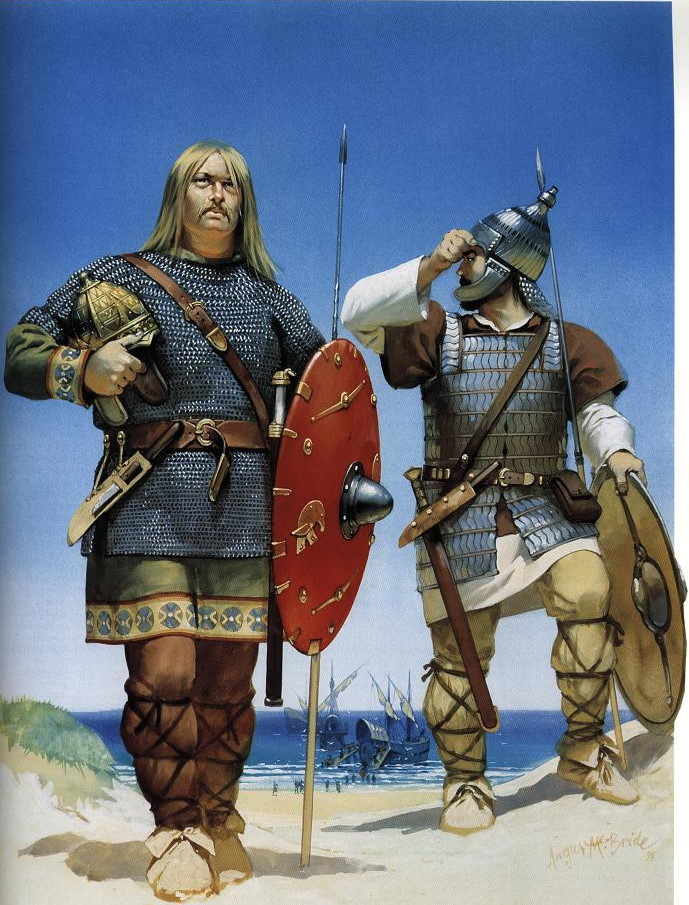

This situation, like the Persian Wars, led increasingly to

the adoption of alien arms and armour by the imperial forces. In the time of

Theodosius, the legionary, with his characteristic crested helmet and cuirass,

was still a recognizable Roman type. But at the same time, legions were

beginning to use exotic weapons such as the spatha – a long broadsword – which

had in Tacitus’ day been employed only by foreign auxiliaries in the Roman

army. Instead of the pilum, some infantry units were now armed with the lancea,

a lighter javelin, to which extra precision and impetus could be given by the

use of an attached sling strap. The terms spiculum and vericulum also indicate

new types of missile weapons. The general tendency was towards lighter kinds of

throwing spears.

Goths in Revolt

In AD 388, with the help of a German general, Theodosius had

suppressed the rebellion of Magnus Maximus, a military pretender based on

Britain, who had extended his power to Gaul and Spain and finally invaded the

central provinces of the Empire. Theodosius’ German general then turned against

him and supported another pretender in Rome, but the Emperor promptly marched

from Constantinople into Italy and extinguished both the Roman rival and his

German supporter. Events took this course because Theodosius was a strong

emperor, able to fight his own wars. Under weak or pusillanimous emperors, the

real power lay with their commanders-in-chief, and these commanders-in-chief

were frequently of Germanic barbarian origin.

The Goths whom Theodosius had settled south of the Danube

remained loyal to him during his lifetime. But their chief, Alaric, who had

commanded a Gothic contingent during the Italian campaign, aspired to a higher

appointment, and after Theodosius’ death he led his people in revolt. Under

Alaric’s leadership, the Goths from the Danube settlement (Lower Moesia), after

briefly threatening the walls of Constantinople, marched southward through

Thrace and ravaged Macedonia and north Greece. They were checked, however, by

the very able Western commander-in-chief, Stilicho, the only officer who was

able to cope with Alaric. As a result of political intrigue, the Emperor

Arcadius at Constantinople ordered Stilicho off Eastern territory. Stilicho

obeyed, and Alaric was then free to continue his march southwards.

Athens paid the Goths to go away, but they invaded the

Peloponnese. Arcadius, having had time to think again, appealed to Stilicho to

come back – and Stilicho came. He reached Corinth with his army by sea,

outmanoeuvred the Goths in the Peloponnese and forced Alaric to make peace. By

a new treaty, the Goths received land to the east of the Adriatic, and Alaric

was proclaimed king of Illyria. It was not a solution which was expected to

last, and it did not.

Alaric’s attitude seems to have been in some ways ambiguous.

He had at first been ambitious for promotion in the Roman army, but when

disappointed had eagerly espoused the cause of nationalistic Gothic

independence, which enjoyed a considerable vogue among the Balkan Visigoths

over whom he ruled. The agreement which he reached with Stilicho seems

temporarily to have satisfied both his Roman and his Gothic aspirations, for

while recognized as king by the Gothic population, he was also granted the

title of Master of the Armed Forces in Illyricum – a top Roman appointment.

“Master of the Armed Forces” was a title which had become

important under Theodosius. In the time of Constantine the Great, the Master of

the Horse (Magister Equitum) and Master of Foot (Magister Peditum) had been

separate appointments. But Theodosius combined the two into a single command

(Magister utrius quo militiae). Officers so ranking might be attached to the

emperor’s staff or given authority over specified regions, as Alaric was in

Illyricum. In the West, the divided command of horse and foot persisted until a

later date, but under an emperor like Theodosius’ son Honorius, who was no

soldier himself, the need for a unified command became imperative, and the

commander-in-chief, who automatically received patrician social status on

appointment, came to be known, curiously, as the Patrician. The old term

patricius, originally applied to aristocratic members of the early Republic,

had been revived by Constantine as an honorary title, but in the fifth century

AD it was often held by successful barbarian officers and indicated supreme

military command.

The Vandals

Stilicho, like Alaric, was an officer of barbarian origin.

He differed in being not a Goth, but a Vandal. In the fifth century AD, the

Vandals were a very active Germanic people, but in comparison with other

barbarian nations, they were not numerous. Their earliest recorded homeland was

in south Scandinavia but, migrating southwards, by the end of the second

century AD they had become the restless western neighbours of Gothic

settlements north of the Danube. A further migration was made as a result of

pressure from the Huns, and in 406 the Vandals crossed the Rhine, ravaged and

plundered Gaul, then made their way into Spain. In these wanderings, they were

accompanied by the Alans from south Russia, but the Visigoths in Spain, acting

under Roman influence, attacked them fiercely and virtually exterminated one

section of their community.

In 429, under the most celebrated of their kings, Gaiseric,

the Vandals, with their Alan associates, crossed into Africa. Their entire

population is reported at this time to have been only 80,000 strong. Probably,

not more than 30,000 of these will have been fighting men. The number is small

when one remembers Ammianus Marcellinus’ instance of a single German tribe

which in the course of 60 years had increased its population from 6,000 to

59,000. Gaiseric soon exerted full control over north Africa. Like other

Germanic nations, the Vandals had made contact with Christianity before they

entered Roman imperial territory. Like many other Germans, also, they had been

converted to an heretical form of Christianity (Arianism). Gaiseric was an

ardent Arian and persecuted the Catholic Christians of north Africa with

fanatical zeal.

The Vandals were notable as a seagoing nation. Perhaps the

experience of the African immigration opened their eyes to the further

possibilities of water transport. Gaiseric acquired a fleet and used it for the

purpose of widespread piracy, against which the western Mediterranean, by the

end of the fifth century, had absolutely no protection. It may seem surprising

that a nation with a long history of overland migration should have developed

in this way, but the Goths, who had similarly reached the Mediterranean in the

third century, had quickly adapted themselves to maritime conditions and

launched sea-borne raids on the Black Sea and further south into the Aegean.

Certainly, the seafaring habit seems to have taken deep root

among the Vandals and it perhaps antedates even the Vandal occupation of

Africa. At the end of the fourth century, Stilicho, adhering to the traditional

methods of his compatriots, transported his army to Corinth by sea. After he

had come to terms with Alaric in 397, he dispatched another sea-borne force to north

Africa to quell a rebellion in that province. Clearly, Rome’s great Vandal

generalissimo was in undisputed command of central and western Mediterranean

waters. History suggests that Stilicho and Gaiseric studied in the same

strategic school.

The weakness of the Vandals, of course, lay in the paucity

of their numbers, and in this they may be contrasted sharply with many other

barbarian nations, who could rely on numbers to compensate for lack of military

skill and sophisticated armament. For this reason, the renowned Byzantine

general, Belisarius, acting on behalf of the Emperor Justinian, was able in the

sixth century to cross with a fleet into Africa and crush the Vandal kingdom

completely. It never revived. We should also notice, in this context, that

Greek seafaring tradition in the East, given full support from Constantinople,

was still able to provide a bulwark against organized piracy during centuries

when the seas and shores of the West were hopelessly exposed to such attackers.