29/30 April 1915

This was the first raid on England to be carried out by a

German military airship.

LZ-38 was the single army airship that carried out the raid,

under the command of Hauptmann Erich Linnarz. It was first reported from the

Galloper lightship as being 30 miles south-east of Harwich, going west, after

11 p.m. on 29 April.

At 11.55 p.m. she crossed the coast at Old Felixstowe and

went straight inland, reaching Ipswich at 12.10 a.m. There, she dropped five

incendiary bombs in the borough, one of which failed to ignite. One fell on a

house in Brookshall Road, setting fire to it and the adjoining house; otherwise

no damage was done and no casualties were caused.

Immediately afterwards, five more incendiary bombs fell at

Bramford, to no effect. At 12.20 a.m. five explosive and eleven incendiary

bombs fell at Nettlestead and Willisham, 7 miles north-west of Ipswich, doing

no damage except for crops. The airship eventually reached Bury St Edmunds, and

for ten minutes circled over the town, going round two or three times. At 1

a.m. she dropped three HE and forty incendiary bombs on the defenceless town.

Luckily, most incendiary bombs simply burnt out causing no damage or were

doused by buckets of water.

The most significant damage was suffered by four business

premises on the Butter Market, where Day’s Boot Makers and adjoining shops were

gutted, and burned until morning. By some miracle, there was only one casualty

– a collie dog belonging to a Mrs Wise.

The airship had now left the area of coast fog; the sky was

quite clear and moonlit at Bury St Edmunds, and the LZ-38 was plainly visible

at a height of about 3,000ft. She therefore hastened to return to the

protection of the fog before she could be attacked, and went off eastward at

high speed, dropping a single HE bomb as she went. No damage was done in either

case.

At 1.15 a.m., she reached Creeting St Mary, 16 miles

east-south-east of Bury St Edmunds, and dropped an incendiary bomb there,

followed by another at Otley; neither causing any harm. At 1.27 a.m. another

fell at Bredfield, 10 miles east-south-east of Creeting St Mary, and at 1.30

a.m. another at Melton, 2 miles from Bredfield, with the same result. The last

bomb, also an incendiary, was harmlessly thrown at Bromeswell, and the airship

proceeded out to sea near Orfordness at about 1.50 a.m.

After turning north along the coast, at 2 a.m. she passed

over Aldeburgh and was last heard of at sea at 2.20 a.m., still going in the

same direction. No action was taken against the Zeppelin; the mobile guns of

the RNAS reached Bury St Edmunds at 1.45 a.m., three quarters of an hour after

the raid, and it was by then too foggy on the coast for aircraft to go up.

10 May 1915

LZ-38, again commanded by Hauptmann Linnarz, was this time

first spotted at 2.45 a.m. over the SS Royal Edward which was moored off

Southend as a prisoner of war hulk. The raider dropped an incendiary bomb close

to the port side of the ship, the flames leaping up to a height 10–12ft and

lasting half a minute. The LZ-38 was travelling towards Southend and dropped

two more bombs in the water between the ship and the shore.

She passed over Southend east–west at 2.50 a.m., dropping

four HE and a large number of incendiary bombs on the town as she went. Two of

the HE bombs failed to explode. After leaving Southend the airship went over

Leigh to Canvey Island where, at 3.05 a.m., the Zeppelin came under fire of the

AA (anti-aircraft) guns at Thames Haven and at Curtis & Harvey’s Explosive

Works, in Cliffe. There were 3in guns mounted at Cliffe and their fire, the

volume of which was probably unexpected, straightaway turned the LZ-38, which

appeared to be hit – although not vitally.

The Zeppelin went back over Southend, dropping more

incendiary bombs there at 3.10 a.m. She headed north-east towards Burnham, and

went out to sea near the mouth of the Crouch. At 4.18 a.m. she passed the

Kentish Knock light vessel, heading east. She passed near Sunk at 4.30 a.m. and

by 5.15 a.m. she had moved south of the Shipwash, after which she headed

towards the Outer Gabbard and out to sea. On returning to Belgium, she was

found to have been holed twice aft by AA (anti-aircraft) fire, a shell having gone

through her stern.

A large number of incendiary bombs, estimated to be about

ninety, were dropped on Southend but, owing to the energy of the fire brigade

surprisingly little damage was done. A timber yard was burnt out and a number

of small fires were started, all of which were brought under control, except

for one in a dwelling house which was completely burnt out. A woman was killed

and a man injured in this house. A private of the 10th Border Regiment was also

injured in the town.

The very heavy load of incendiary bombs carried by the

airship was remarkable, as is the time at which the raid was carried out, just

before dawn. As this time was not again chosen for a further raid, it was

evidently deemed unsuitable for some reason. The height of the airship was

unusual for this period, being estimated at 9,000–10,000ft, which is much

higher than previously.

During the raid a message was dropped on the town, written

on a piece of cardboard in blue pencil: ‘You English. We have come and will

come again soon. Kill or Cure. German.’

17 May 1915

LZ-38, with Hauptmann Linnarz, was spotted again seven days

later at 12.30 a.m. hovering off North Foreland for some time,and appeared to

have dropped some bombs in the sea. She then approached Ramsgate. On being

fired at from drifters at sea, she first went east and then northwards and was

off the Tongue lightship shortly after 1 a.m. At 1.40 a.m. she came overland

again at Margate and flew across Thanet, reaching Ramsgate at 1.50 a.m.

She dropped a number of bombs, apparently four HE and about

sixteen incendiaries, on the town. One HE bomb struck the Bull and George

Hotel, penetrating to the basement and blowing out the whole front of the

building. A man and a woman who were on the second floor were seriously injured

and died three days later; another woman was slightly injured. No other

casualties were caused, though bombs fell all over the town and in the harbour.

A few buildings and some fishing smacks were damaged. After throwing the bombs,

the airship went out to sea under hot rifle fire and disappeared in the clouds.

She then proceeded down the coast, and came inland again

about 2.10 a.m. at Deal, where she hovered for a short time with propellers

stopped. At 2.25 a.m., LZ-38 approached Dover and was engaged by the AA guns of

the garrison. In all, five rounds of 6-pdr and twenty-eight rounds of 1-pdr

ammunition were fired. On being caught by the searchlights and fired at, the

airship at once rose to a height of at least 7,000ft, dropping bombs as she did

so, and emitted a dense cloud of vapour in which she disappeared (this was a

discharge of water ballast).

The bombs fell at Oxney, 3½ miles from Dover. They were all

incendiary, and thirty-three were found. No damage was done by any of them.

The airship carried on north, was fired on by the guard ship

in the Downs at 2.50 a.m., hovered about in the neighbourhood of the North

Goodwins until 3.25 a.m. and then went back to Belgium after day had dawned.

She passed over the British lines at Armentières at about 4.20 a.m.

While over Ramsgate, the lights of London were discernible

from the airship, but her commander’s instructions expressly forbade his

venturing far inland and no attempt was made to raid London. The estimated

value of the damage caused by the raid was £1,600.

26 May 1915

LZ-38 and Hauptmann Linnarz paid their second visit to

Southend on this night, several weeks later. The raid was clearly a repetition

of his earlier reconnaissance of the route to London, special attention being

paid to the mouth of the River Blackwater.

At 9.18 p.m. LZ-38 passed Dunkirk going west, and at 10.30

p.m. appeared off Clacton-on-Sea. She then passed south-west via

Bradwell-juxta-Mare at 10.50 p.m. to Southminster at 10.53 p.m. Here, she was

fired on with fifty-seven rounds from a pom-pom.

LZ-38 turned south to Burnham-on-Crouch shortly before 11

p.m., passing over Shoeburyness at 11.05 p.m., where the airship came under

fire from a 3in AA gun and veered westwards to Southend. Here, at 11.13 p.m.,

she dropped twenty-three small HE bombs and forty-seven incendiaries. Two women

were killed (one of them, unfortunately, from a fragment of AA shell), a girl

was injured and several other people received minor injuries.

LZ-38 went off to the north-east, and was again engaged by

Shoeburyness AA fire at 11.20 p.m. (the 3in gun at Shoeburyness fired a total

of twenty-four rounds HE and thirteen rounds of shrapnel). She passed Wakering

at 11.25 p.m. then left via Burnham, where she was fired on with 200 rounds of

rapid fire by A Company, 2nd/8th Battalion Essex Regiment, thence to Bradwell

and out to sea at the mouth of the Blackwater at 11.45 p.m. The monetary damage

caused by the raid was estimated at £947.

It was noted that the small HE bombs were more like

grenades, weighing about 5lb each. The GHQ report stated:

These clearly had no other object than the killing or

maiming of as many people as possible. Owing to their small size the damage

they could inflict to well-built house property was relatively slight but as

the casing of the bomb was serrated in the same manner as that of a Mills

grenade, the explosion of such a bomb in a crowded thoroughfare or building

would cause serious casualties.

The First Raid on London

LZ-38 was first reported on 31 May passing Dunkirk at 8.30

p.m. She crossed Calais at 8.55 p.m. and made for the North Foreland, passing

Margate, where she was fired at with 500 rounds from the Maxim machine guns of

the Southern Mobile RNAS section at 9.42 p.m. Other .45 Maxim machine guns of

the Southern Mobile RNAS opened fire on her from Reculver at 9.50 p.m. and she

seems to have moved over to the Essex shore. Here she was fired upon with

twelve rounds of shrapnel shell by the 3in gun at Shoeburyness at 10.12 p.m.

LZ-38 passed inland between Rochford and Rayleigh at 10.25

p.m., reaching Wickford at 10.35 p.m. Later, at 10.50 p.m., she passed

Brentwood and then seems to have hesitated as to her course; her commander was

evidently fixing his exact position with regard to London.

LZ-38 then came straight in, passing between Woodford and

Wanstead at 11.15 p.m. The airship was seen over London for the first time,

about 400 yards away from Stoke Newington Station and, at this point, commenced

dropping bombs at 11.20 p.m.

The first bomb to drop in the Metropolitan Police area was

an incendiary. It fell on 16 Alkham Road, Stoke Newington, penetrating into two

bedrooms and destroying their contents by fire. The spot where this bomb fell

is about 300 yards south-east of Stoke Newington Station and it may possibly

have been aimed at the station. The next bomb was also an incendiary and it

fell on 8 Chesholm Road, falling through the roof of the back bedroom but

without doing any further damage. This was followed by three HE grenades that

fell on 41, 43 and 45 Dynevor Road, Stoke Newington. At the first house the

windows and doors were blown out, but nos 43 and 45 also had the back

extensions of each house practically demolished and the rest of the doors and

windows blown out.

The airship then steered a course due south about 500–600

yards west of the main Kingsland–Stoke Newington road, which was doubtless

visible. Bombs were then thrown in rapid succession, the next being an

incendiary which fell at 27 Neville Road, Stoke Newington, completely gutting

the premises. This was followed by an HE grenade, which landed in the roadway

of Neville Road and failed to explode.

An incendiary bomb fell on a shed at the rear of 21 Neville

Road, but caused no fire, and another incendiary followed this at 47 Neville

Road, falling through the roof to the floor below without causing any fire.

Another incendiary bomb was dropped at 6 Allen Road, and this went through the

roof of the house to the ground floor, gutting two rooms and injuring four

children slightly. At 69 Cowper Road, an incendiary bomb fell into a small water

tank without causing any serious damage, while at 71 Cowper Road another

incendiary caused a small fire.

The next bombs to fall were two grenades at 102 Shakespeare

Road. One struck the coping of the house and another fell on the front steps.

Considerable damage was done to no. 102 and the adjoining houses. Three more

incendiary bombs were thrown into Barrett’s Grove, Arundel Grove and St

Matthias’ Road, Stoke Newington, but no damage was caused.

Two HE grenades were dropped on Woodville Grove. These fell

into gardens and did not explode. They were followed by three incendiaries and

an HE grenade dropped in Mildmay Road, which caused very slight damage. From

this point onwards to the Shoreditch Empire Music Hall no grenades were thrown.

More incendiaries fell in Queen Margaret’s Grove and King Henry’s Walk without

doing any damage; two, however, caused a fire in Ball’s Pond Road in which two

people were burnt to death, and a man and four women injured.

Incendiary bombs were dropped all the way down Southgate

Road at close intervals, but fortunately they all fell into gardens or onto

roadways and caused no damage. After crossing at Regent’s Canal, an incendiary

bomb was dropped at 6 Witham Street but only caused a slight fire, which was

extinguished by the occupier.

The airship now veered more to the south-east, and dropped

several incendiary bombs, causing only slight damage, until at 28 Hemsworth

Street, Hoxton, where the premises were gutted, as were those at 31 Ivy Lance,

Hoxton, where an incendiary bomb caused severe damage by fire and slightly

injured a child. The next bomb, dropped at Bacchus Walk, Hoxton, destroyed the

premises, and hit and seriously injured a soldier. Between this point and the

Shoreditch Empire, three more incendiary bombs were dropped without causing any

serious damage, two of them falling onto stone pavements.

Subsequently, four incendiary bombs were dropped together,

three falling on the Shoreditch Empire Music Hall and the other on the house

next door; the damage in both cases was slight. A grenade was also thrown at

this point, and this fell onto the pavement in front of the music hall without

causing any casualties. The audience was in the building at the time, and any

tendency to panic was averted by the promptitude of the manager in addressing

the audience from the stage.

The next bomb was an incendiary, and fell on the premises of

Hopkins & Figg’s, drapers of Shoreditch, without causing any serious

damage. There were about thirty female assistants sleeping on the premises and

the consequences might have been very serious had the bomb set the building on

fire.

Three incendiary bombs fell on Bishopsgate Street Goods

Station, but the fires were promptly extinguished by the men on duty. Two

incendiaries and one HE grenade fell into Pearl Street, Shoreditch, but did no

great damage. These were followed by three incendiary bombs in Princelet

Street, and an HE grenade in Fashion Street, none of which caused any serious

damage.

Altogether, four men (including two soldiers), two women and

two children were injured in Hoxton and Shoreditch. Fortunately there were no

fatalities.

The airship then passed over Whitechapel. Incendiary bombs

which fell on Osborn Street, Whitechapel and near Whitechapel Church did no

damage. A HE grenade fell into a large tank of water at the whisky distillery

of Johnnie Walker & Sons, Whitechapel, followed by three incendiaries in

Commercial Road East, none doing any harm.

LZ-38 began to turn due north-east and, at the same time,

dropped seven HE grenades in close succession. The first of these fell in a

yard at 13a Berners Street, injuring a horse, followed by two on the same spot

in Christian Street, Whitechapel. The casualties here were severe, as two

children were killed, with five people seriously hurt and five slightly

injured.

Another HE grenade fell in Burslem Street, St George’s, but

failed to explode; followed by another in Jamaica Street and another in East

Arbour Street, with similar results. The next bomb was also a grenade that fell

on Charles Street, Stepney, but only broke some glass. The next two bombs were

incendiaries at 130 Duckett Street and 16 Ben Jonson Road, Stepney, and these

caused slight fires in both instances. They were closely followed by a grenade,

which also fell on Ben Jonson Road, but caused no damage.

It is worthy of note that the commander of LZ-38 made no

attempt to attack the docks which, at this point in the raid, lay only about 1

mile away from him to starboard.

A relatively large distance of 3 miles now elapsed before

the next bombs were thrown. The fact that the airship was passing over the

relatively thinly inhabited areas on each side of the River Lea could

apparently be seen from the airship and, for this reason perhaps, no bombs were

thrown hereabouts. The next bombs released were two incendiaries, which fell at

Wingfield Road and Colgrave Road, West Ham, but did no damage. A grenade in

Florence Street, Leytonstone, caused little harm, as did others which fell at

Park Grove Road, Cranleigh Road, Dyer’s Hall Road and Fillebrook Road. The last

bomb in Fillebrook Road, fell at about 11.35 p.m. The casualties at Leytonstone

amounted to three people being slightly injured.

The total number of bombs dropped in the Metropolitan Police

area were:

30 HE grenades at 5lb each = 150lb

89 Incendiary bombs at 25lb each = 2,225lb

This weight represents a total of 1 ton 1cwt and 23lb of

bombs dropped on London.

LZ-38 now went off east, passing Brentwood at 11.55 p.m. and

was spotted between Burnham and Southminster at 12.30 a.m. Her commander

clearly had some difficulty in fixing the locality of his point of departure –

no doubt the mouth of the Crouch – and hesitated for a few moments just as he

had outside London, before deciding his position with regard to the coast. The

airship was fired upon by an AA gun at Southminster and the mobile guns of the

RNAS at Burnham. LZ-38 went out to sea at the mouth of the Crouch about 12.40

a.m. The estimated monetary value of the damage caused by the raid was

estimated at £18,596.

The question of the height at which this airship was

travelling was of some importance. At Shoeburyness her height was estimated at

7,500ft by the military authorities. The reports of the RNAS, however, speak of

her as having passed near that place (probably on her return) at 10,000ft and,

‘at no part of its journey does it appear to have descended much below this elevation’.

No action against the airship was taken by the AA guns in

London, then controlled by the RNAS. The reason given for this inaction was the

airship was so high that it was neither seen nor heard: ‘There is no authentic

case of anyone having been able to see it during its passage over London … it

was faintly heard by the gun-station at Clapton.’ This statement appears to be

substantiated, but at the same time the accurate manner in which the airship

followed the straight line of the Kingsland Road from Stoke Newington to

Shoreditch, at a height of 10,000–11,000ft, even by moonlight, is remarkable.

So great a height was not attained by any of the other

airships, whether army or naval, which raided London later in the year. Their

height was between 7,000 and 10,000ft during the raids of 7 and 8 September,

until they had got rid of their bombs and were going off. On 13 October,

however, the height of 12,000ft was attained by a naval airship, but it was not

until autumn 1916 that this became the normal raiding height.

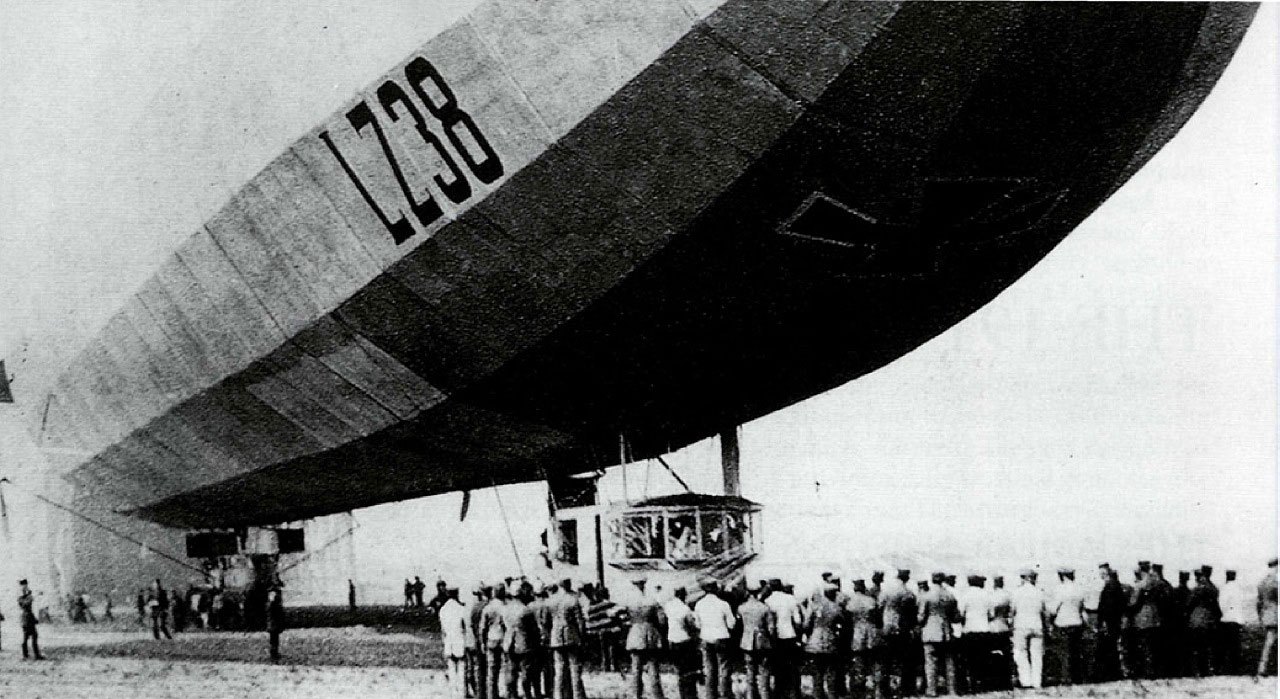

Hauptmann Erich Linnarz and his crew pose for photographs after LZ38’s first raid.

‘I was London’s First Zepp Raider’ by Major Erich Linnarz

Major Linnarz, who was commander of Zeppelin LZ.38, had been

four times over England before, on May 31, 1915, he succeeded in reaching

London. This was London’s first air raid.

It was not until January 1915 that the Kaiser at last

sanctioned the bombing of England, and not until four months later that he was

prevailed upon by his advisers to give his consent to attacking London. The

proud ship LZ.38, the latest product of Count Zeppelin’s works at

Friedrichschafen on Lake Constance, which I commanded, was one of those

detailed for the job.

On the morning of May 31 orders in cipher were brought from

Berlin to me at Brussels to raid London. Preparations for the flight were

carried out all that day. Engines were tested, ballast tanks examined, the

radio apparatus thoroughly overhauled, and the huge deflated envelope closely

inspected for flaws. Presently there was the hiss of gas and slowly the monster

took a more rigid shape. Then the bomb-racks were loaded. One hundred and

nineteen bombs there were in all – eighty-nine incendiary, thirty high

explosive ones. A ton and a half of death.

As the perspiring soldiers wheeled the infernal things on

trucks before placing them in position, the setting sun sank behind the shed

and stained the sky a deeper and more ominous red. My crew, clad in their

leather jackets and fur helmets, were standing in groups on the landing ground.

A siren sounded shrilly and they moved to the shed, entered the gondola and

took up their posts. Gently guided by ropes the ship slid smoothly forward. The

sounding of a second siren indicated that the ship was clear of its shed.

‘Hands off, ease the guides,’ I shouted. The men at the

ropes let go.

Great Eddies of dust swept through the air as the final test

to the mammoth propellers was given. An officer approached and told me all was

ready, I stepped in, gave a signal, and mysteriously the ship soared upwards.

We were on our way to London.

From my cabin, with its softly lit dials – everyone with a

story to tell – its maps, its charts, and compass, I could hear the rhythmic

throb of the engines; feel the languorous swing of the gondola as we rode

smoothly through space. Over invaded Belgium we flew. Here it was that one of

my crew at the helm reported that he had sighted what he thought to be a hostile

airship approaching. For safety I altered course and steered in the direction

of Ostend.

Often raiding Zeppelins, on their way out from Belgium to

England, encountered enemy craft endeavouring to intercept their passage. But,

as it afterwards turned out, this one was only Captain Lehmann, who was killed

in an airship crash in America last year, on one of the other Zeppelins

detailed to raid England. He had left Namur earlier, also with London as his

aim, but over the Channel he had broken a propeller, which had pierced his

gas-bag and forced him to return to his base.

He was on his way back when we saw him. None of the other

ships reached London that night, but discharged their bombs on East Coast

towns. On, on we sped. It was a beautiful night – a night of star spangled

skies and gentle breezes, a night hard to reconcile with a purpose as grim as

ours. And then the glimmer of water showed below and we knew we were over the

sea. Tiny red specks winked at us. They were patrol boats keeping their

ceaseless watch in the Channel, and we were looking down their funnels into the

glowing heart of their stoke-hold furnaces. England!

We crossed the black ridge of the coast. Immediately from

below anti-aircraft guns spat viciously. We could hear the shells screaming past

us. We increased our altitude and our speed. Across the Thames estuary we

raced, wheeling inland at Shoeburyness, over Southend, which I had raided the

week before – and then, following the gleaming river, we made straight for the

capital. Twenty minutes later we were over London. There below us its great

expanse lay spread. I knew it all so well. I had spent several months there

five years before. There seemed to have been little effort to dim the city.

There were the old familiar landmarks – St. Paul’s, the Houses of Parliament,

and Buckingham Palace, dreaming in the light of the moon which had now risen.

I glanced at the clock. It was ten minutes to eleven. The

quivering altimeter showed that our height was 10,000 feet. The air was keen,

and we buttoned our jackets as we prepared to deal the first blow against the

heart of your great and powerful nation.

Inside the gondola it was pitch dark save for the glowing

pointers of the dials. The sliding shutters of the electric lamps with which

each one of the crew was provided were drawn. There was tension as I leaned out

of one of the gondola portholes and surveyed the lacework of lighted streets

and squares. An icy wind lashed my face.

I mounted the bombing platform. My finger hovered on the

button that electronically operated the bombing apparatus. Then I pressed it.

We waited. Minutes seemed to pass before, above the humming song of the

engines, there arose a shattering roar.

Was it fancy that there also leaped from far below the faint

cries of tortured souls?

I pressed again. A cascade of orange sparks shot upwards,

and a billow of incandescent smoke drifted slowly away to reveal a red gash of

raging fire on the face of the wounded city.

One by one, every thirty seconds, the bombs moaned and

burst. Flames sprang up like serpents goaded to attack. Taking one of the

biggest fires, I was able by it to estimate my speed and my drift. Beside me my

second in command carefully watched the result of every bomb and made rapid

calculations at the navigation chart.

Suddenly from the depths great swords of light stabbed the

sky. One caught the gleam of the aluminium of our gondola, passed it, retraced,

caught it again, and then held us in its beam. Instantly the others chased

across the sky, and we found ourselves moving through an endless sea of

dazzling light. Inside the gondola it was brighter than sunlight. Every detail

of the car was thrown in sharp relief. The crew at their posts looked like a

set of actors grouped in the limelight without their make-up. And so began a

game of hide and seek in the sky. The helmsman and I tried every way of eluding

the searchlights, practising every trick of navigation.

Then came the bark of the batteries. Shells shrieked past

us, above us, below us. There were glowing tracer shells which we had never

seen before, but had heard all about – slim projectiles that tore a hole in the

ship’s fabric and then burst into flame. It was this thought that sent us home

quickly. We had been over London for an hour. Soon we left the thrusting searchlights

behind. We could see ahead of us the sea, through which the moon had laid a

silver path to guide us home. As we crossed the black ridge of the shore we

were met with a further attack from the anti-aircraft guns at Burnham and

Southminster. I think our gondola light, now alight and casting a feeble glow

over the cabin, perhaps had betrayed us. I put it out. Shell after shell

whizzed past, some of them the dreaded incendiary type. Some burst dangerously

near. On, on we flew, and at last we were out of range and the firing died

down.

Now a new menace threatened us – aeroplanes. We went in

dread of these since your pilots had orders that if they failed to reach us

with the machine-gun fire they were to climb above us and ram our gas-bags with

their machines. Evidently the supreme sacrifice meant nothing to these brave

men. One by one they came from the airfields that had been established round

the coast to intercept returning raiders. My look-out thought he spotted one

flying towards us. Higher we rose out of reach. The British aeroplanes were

faster than we were, but they couldn’t reach our height limit.

Presently in the fading moonlight, we could see the waves

beating against the Belgian coastline far below. We were feeling cold and

hungry, exhausted and spent from the high-pitched hours of that night – rather

like the remorseful reveller returning in the hour before the dawn. It was

almost dawn. The first vague light was edging the horizon as we flew over

invaded Belgium. We had been away ten hours. The first attack on London had

been accomplished. Our bomb rack was empty. Behind us we could faintly make out

the red glow of fire on the sky’s rim. It was ravaged London. And as we sank to

the earth and the gondola bumped across the landing-ground at Brussels-Evere,

the sun, rising in front of the Zeppelin sheds, smeared the sky with crimson

streaks as though fingers dipped in blood had been drawn across the horizon.