Until just five years ago, Manchurians were little more

than backward bandits squabbling over pieces of torn fiefdoms. Today, we

operate our own air force against all the enemies of a modernized Manchukuo.

-Nobuhiro Uta, 1st Lieutenant, Doi ManshuTeikoku Kugun’

In 1640, Ming Dynasty control over China was falling apart.

Widespread crop failures, followed by starvation on a scale too massive for

government redress, and peasant revolts broke out to badly shake the nearly

300-year-old order. Taking advantage of these upheavals, Manchu raiders from

the north approached the capital on May 26, 1644. Beijing was defended by an unfed,

unpaid army unwilling to oppose the invaders, who entered its gates just as the

last Ming emperor hung himself on a tree in the imperial garden.

The Manchus replaced his dynasty with their own, the Qing

(or “clear”), that ruled until the early 20th century. Demise of the

Manchurian imperium in 1912 had been preceded by decades of corruption,

military defeats, and foreign exploitation, leading inevitably toward

revolution. Organized society dissolved, as private armies fought each other

for control during the so-called Warlord Era.

Observing this calamitous decline from afar were the

Japanese. They knew that someone would eventually emerge from the chaos to

unify the country, thereby fulfilling Napoleon’s dire warning about China being

a sleeping giant that, once awakened, would terrify the world. In 1931,

Japanese forces invaded Manchuria to extirpate its contentious warlords,

restore some semblance of social order, and, most importantly to themselves,

create a buffer state, rich in natural resources, between Japan and the USSR.

On February 18, 1932, Manchukuo was established with

assistance from former Qing Dynasty officials, including Pu-Yi, “the last

emperor.” Unlike Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 film of that name, the new

“State of Manchuria” was not entirely a Japanese “puppet;’ or

colony, although it had elements of both. Like most Asian monarchs of his time,

including Japan’s Emperor Hirohito, Pu-Yi was mostly a figurehead: the nation’s

symbolic personification. Real power lay in the hands of state council cabinet

ministers, who belonged to the Xiehehui Kyowakai. This “Concordia

Association” embodied the principles of Minzoku Kyowa, the “concord

of nationalities;’ a pan-Asian ideology aimed at making Manchukuo into a

multi-ethnic nation that would gradually replace the Japanese military with

civilian control.

By granting different ethnic groups their communal rights

and limited self-determination under a centralized state structure, a balance

was created between federal power and minority rights, thereby avoiding the

same kind of separatism that had undermined the Hapsburg’s Austro-Hungarian

monarchy or Russia’s Czarist empire. Accordingly, emigres were allowed their

own independent groups, which included a wide spectrum of agendas, from White

Russian Fascists and Romanov monarchists, to Jews involved in several Zionist

movements. Together with these diverse populations, Mongols, Hui Muslims, and

Koreans, as well as native Manchu, Japanese settlers, and the majority of

Chinese found workable representation in the Concordia Association that

dispensed with former animosities.

Because the rights, needs, and traditions of each group were

officially respected, religious liberty was guaranteed by law. Mongol lamas,

Manchu shamans, Muslim ahongs, Buddhist monks, Russian Orthodox priests, Jewish

rabbis, and Confucian moralists were equally supported by the state.

Corporatist, anticommunist and anticapitalist, Minzoku Kyowa aimed at class

collaboration by organizing people through religious, occupational, and ethnic

communities. Manchukuo was intended to be the ideal and standard by which the

rest of China was to be reconstituted.

Other similar states set up by the Japanese were the

Mangjiang government for Inner Mongolia, the Reformed Government of the

Republic, and the Provisional Government of the Republic for the eastern and

northern areas of China, respectively. These last two were combined by 1940 in

the Nanjing National Government headed by Wang Jingwei, perhaps the most

brilliant Chinese statesman of the 20th century. After Sun Yat-sen’s death in

1925, as described in Chapter 13, Jingwei became the leader of the Kuomintang,

China’s Nationalist Party, but was subsequently ousted by backstage intrigue to

put Chiang Kai-shek in control.

Jingwei believed with the Japanese that China only avoided

being a military, economic, and ideological threat to the outside world and

itself, while preserving its culture from foreign influences, by a

decentralized system of cooperative independence for the various provinces,

with emphasis on their ethnic individuality. In this, the Japanese envisioned

themselves as the power center of Asia’s Co-Prosperity Sphere. Heavy Japanese

investment helped Manchukuo to become an industrial powerhouse, eventually

outdistancing Japan itself in steel production.

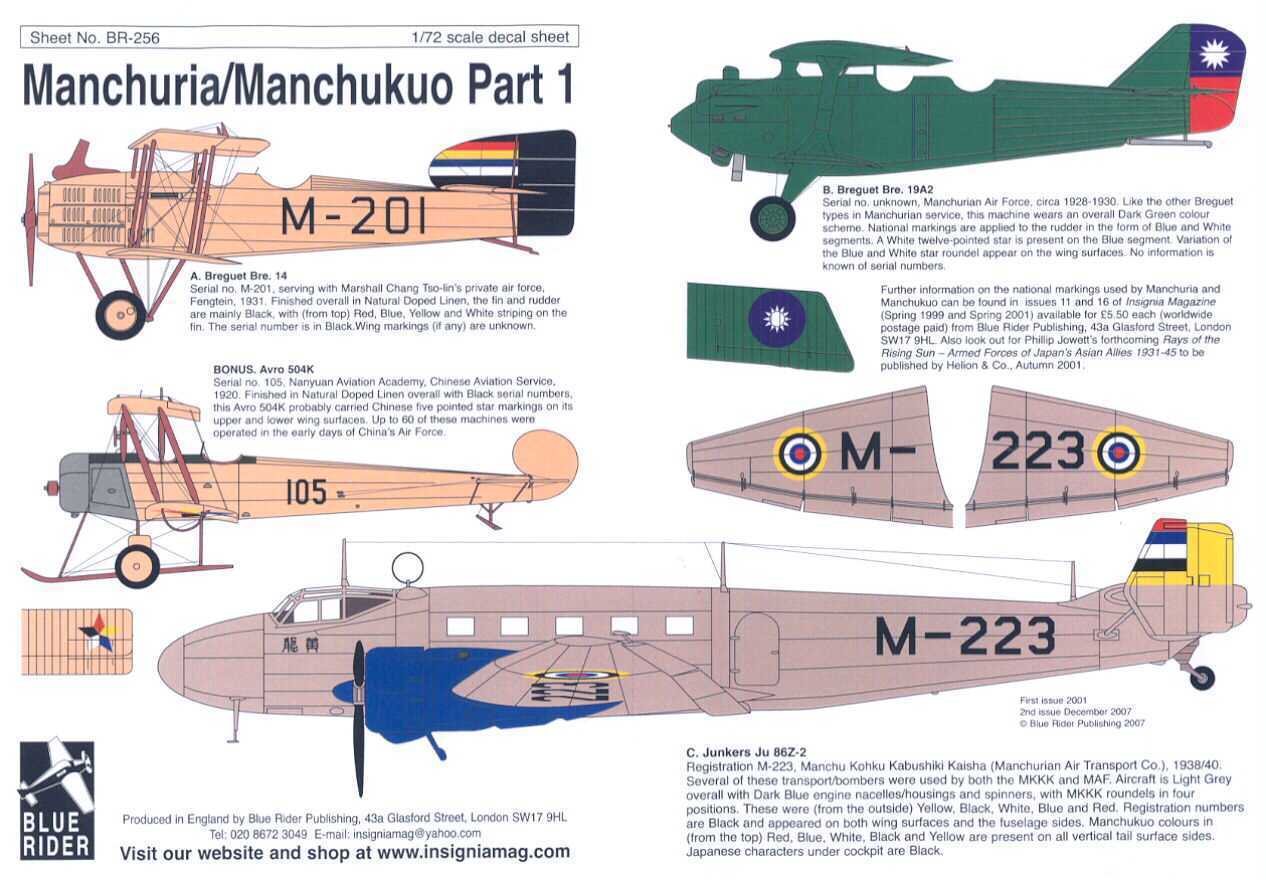

Manchuria operated its first airline, the most modern in

Asia outside Japan. Flying with the Manchukuo Air Transport Company were

Junkers Ju.86s and Fokker Super Universals. The German Junkers was powered by a

pair of Jumo 207B-3/V, 1,000-hp diesel engines, able to carry its 10 passengers

nearly 1,000 miles above 30,000 feet, making it an ideal transport for China’s

mountainous terrain.

The Dutch-designed Fokker F.18 Super Universal was actually

produced in the United States during the late 1920s, later manufactured under

license by Canadian Vickers and Nakajima in Japan. Chosen for its ruggedness,

especially the reliability of its 450-hp Pratt and Whitney Wasp B engine in

very cold conditions, a Super Universal known as the Virginia served in Richard

E. Byrd’s 1928 Antarctic expedition. He additionally valued the conventional,

eight-place, high-wing, cantilever monoplane for its 138-mph performance at

19,340 feet over 680 miles.

Even before the Manchukuo Air Transport Company was renamed

“Manchukuo National Airways;’ the city of Changchun had likewise undergone

a change to Xinjing, the “New Capital” of Manchukuo. The former

whistle-stop town was transformed almost overnight into a beautiful, modern,

and large city, the most culturally brilliant in China at the time. Manchukuo

was officially recognized by 23 foreign governments from all the Axis powers

and the USSR to El Salvador and the Holy See. The League of Nations denied

Manchukuo’s legitimacy, however, prompting Japan’s withdrawal from that body in

1934, while the United States opposed any change in the international status

quo “by force of arms;’ as stated by America’s Stimson Doctrine.

Still, Manchukuo experienced rapid economic growth and

progress in its social systems. Manchurian cities were modernized, and an

efficient and extensive railway system was constructed. A modern public

educational system developed, including 12,000 primary schools, 200 middle

schools, 140 teacher preparatory schools, and 50 technical and professional

colleges for its 600,000 pupils and 25,000 teachers. There were additionally

1,600 private schools; 150 missionary schools; and, in the city of Harbin, 25

Russian schools. By 1940, of Manchukuo’s 40,233,950 inhabitants, 837,000 were

Japanese, and plans were already afoot to increase emigration by 5 million

persons over the next 16 years, in the partial relief of Japan’s overpopulation

crisis.

Bordering as Manchukuo did the Russian frontier, the

necessity for self-defense was apparent. In February 1937, an air force, the

Dai Manshu Teikoku Kugun, was formed. To begin, 30 officers were selected from

the Imperial Army for training with Japan’s Kwantung Army at Harbin. By late

summer, their first unit was established at the Xinjing airfield under the

command of 1st Lieutenant Nobuhiro Uta. His taskto make something of the

fledgling service-was daunting, because he had only a single aircraft at his

disposal, a World War I-era biplane.

The Nieuport-Delage Ni-D.29 had made its prototype debut in

August 1918 and looked every bit its age with its open cockpit and fixed tail

skid. Even then, the French-built pursuit aeroplane did not pass muster,

because it could not achieve altitude requirements. The Ni-D.29 received a new

lease on life when, stripped of its cumbersome military baggage and its Gnome

9N rotary engine replaced by a 300-hp HispanoSuiza 8Fb V-8, it won eight speed

records, including the Coupe Deutsche and Gordon Bennet Trophies of 1919 and

1920, respectively.

Nieuport-Delage executives cashed in on the aircraft’s new

prestige by making it a lucrative export to Belgium, Italy, Spain, Sweden,

Argentina, Japan, and Thailand. Their swift model saw action in North Africa,

dropping 20-pound antipersonnel bombs on native insurgents unhappy with French

and Spanish colonialism. By 1937, the old double-decker’s top speed of 146 mph

and 360-mile range made it something of a relic, but Lieutenant Uta made good

use of its forgiving handling characteristics in the training of his novice

aviators.

Appeals to Japan resulted in more modern aircraft for the

nascent Dai Manshu Teikoku Kugun. First to arrive were examples of a Kawasaki

KDA-2 reconnaissance biplane. It had been designed specifically for the

Imperial Japanese Army by Richard Vogt, an aero engineer from Germany’s

renowned Dornier Flugzeugewerke. Following successful trials, the KDA-2 entered

production with Kawasaki as “Type-88-1, in 1929. Its unequal span wings

and slim, angular fuselage married to a 600-hp BMW VI engine provided a

respectable range of 800 miles at 31,000 feet.

The aircraft’s remarkable stability and rugged construction

lent itself well to the light-bomber role when fitted with 441 pounds of bombs.

Lieutenant Uta’s men also received the Nakajima Type 91, until recently

replaced by the Kawasaki Type 95, Japan’s leading fighter. The parasol

monoplane’s Bristol Jupiter VII, 9-cylinder radial engine was rated at 520 hp,

allowing a service ceiling of 29,500 feet and 186-mph maximum speed. Twin

7.7-mm machine-guns synchronized to fire forward through the propeller arc were

standard for the time.

In July 1938, Soviet troops violated the 78-year-old Treaty

of Peking between Russia and China by establishing their common Manchurian

border, a move that alarmed the Japanese, suspicious of Stalin’s plans for a

Communist China. On the 15th, Japan’s attache in Moscow called for the

withdrawal of newly arrived Red Army forces from a strategic area between the

Shachaofeng and Changkufeng Hills west of Lake Khasan, near Vladivostok. His

demand was rejected because, he was told, 1860’s Treaty of Peking was invalid,

having been signed by “Czarist criminals”2 Soon after, he learned

that the Soviets had relocated the original 19th century demarcation markers to

make their territorial claims appear legitimate.

Japan answered this deception on the 29th by launching its

19th Division and several Manchukuo units at the Red Army’s 39th Rifle Corps,

without success. Although the Nakajima fighter planes stayed behind for

homeland defense, the Manchurians used their Kawasaki reconnaissance aircraft

to scout Russian weak spots without being detected. Based on photographic

information made available by the high-flying biplanes, the Japanese renewed

their offensive on July 31, this time expelling the enemy from Changkufeng Hill

in a nighttime attack. Beginning on the morning of August 2, General Vasily

Blyukher, commanding the Far Eastern Front, ordered a massive, relentless,

week-long artillery barrage that drove the Japanese and Manchurians back across

the border. Hostilities ceased on August 11, when a peace brokered by the

United States came into effect, and Soviet occupation of the compromised

Manchurian border was affirmed.

Far from being honored as the victor of the short-lived

campaign, General Blyukher was arrested by Stalin’s political police and

executed for having suffered higher casualties than the enemy. Russian dead

amounted to 792, plus 2,752 wounded, compared with 525 Japanese and Manchurians

killed, 913 wounded.

Although the Changkufeng Incident, or Battle of Khasan, as

it is still sometimes known, was a Japanese defeat, it afforded the young Dai

Manshu Teikoku Kugun its first operational experiences. More were to come in

less than a year during another, far more serious frontier dispute with the

USSR, when Manchukuoan horse soldiers drove off a cavalry unit of the Mongolian

People’s Republic that had crossed into Manchuria across the Khalkha River,

near the village of Nomohan on May 11, 1939.

Forty-eight hours later, they returned in numbers too great

to be removed by the Manchurians alone. The next day, Lieutenant-Colonel Yaozo

Azuma, leading a reconnaissance regiment of the 23rd Division, supported by the

64th Regiment of the same division, forced out the Mongols. They returned yet

again later that month, but as the Japanese moved to expel them, Azuma’s forces

were surrounded and decimated by overwhelming numbers of the Red Army on May

28; his men suffered 63 percent casualties.