Ancient seafaring was largely dependent on weather

conditions. Sailing was restricted to the annual sailing season and was only

possible in good weather, and most voyages followed the coasts. This practice

continued all over the world until steam engines became widely used in ships in

the nineteenth century. The sailing season in the Mediterranean began in March

and lasted until November; for the rest of the year the ships stayed in port

unless an urgent voyage had to be made. Sailing in winter was avoided because

cloud, fog and mist made navigation difficult and winter storms were dangerous.

Seafarers preferred sailing close to the coast and used landmarks such as

promontories and islands to locate their position. On longer voyages they would

venture further out to sea but tried to ensure that the coast was always

visible. They used the sun and night sky for navigation; the constellation of

Ursa Minor was known in the ancient world as Stella Fenicia. The sailors were

familiar with the winds and sea and land breezes and took advantage of them.

Currents and tides did not generally play a significant role in Mediterranean

seafaring except in narrow channels such as the Chian Strait, the Strait of

Messina and the area of Syrtis Minor. Coastal routes were preferred, not only

because of the protection they offered in bad weather but also because most of

the ships, and especially the warships, had little room to store water and

food, so easy access to the coast was essential to obtain supplies. This

necessity became one of the basic elements in dictating strategy in ancient

warfare at sea: warships could only operate in areas where they could reach the

coast in order to take on water and food and rest their crews. As a result, the

control of harbours and landing places was most important and this can be seen

in the strategies adopted by Rome and Carthage during the conflicts.

Warships worked in cooperation with the army, to transport

troops to attack and ravage enemy territory. Raids were intended to put

political, economic and psychological pressure on the enemy. The rowers had

multiple tasks to perform. As well as rowing and beaching the ships, they built

siege engines when needed and fought on land. Fleets were used to escort

transport vessels and to support or disrupt sieges. Sea battles resulted from

situations where rival powers fought for control of territory that offered safe

harbours and landing places; they were most likely to occur when one side was

intent on taking over an area controlled by a rival. For example, in 260 in

Mylae the Romans defeated the Punic fleet and then started to operate on the

north coast of Sicily, and in 217 a Roman victory at the Ebro allowed Rome to

extend its influence on the Spanish coast. During the Punic Wars there were

many sea battles; in contrast, the First and Second Macedonian Wars saw no sea

battles when the Roman navy established itself in Greece. This was because

during these wars, Rome, with its allies, possessed overwhelming power at sea,

which Philip of Macedon’s fleet was not strong enough to challenge.

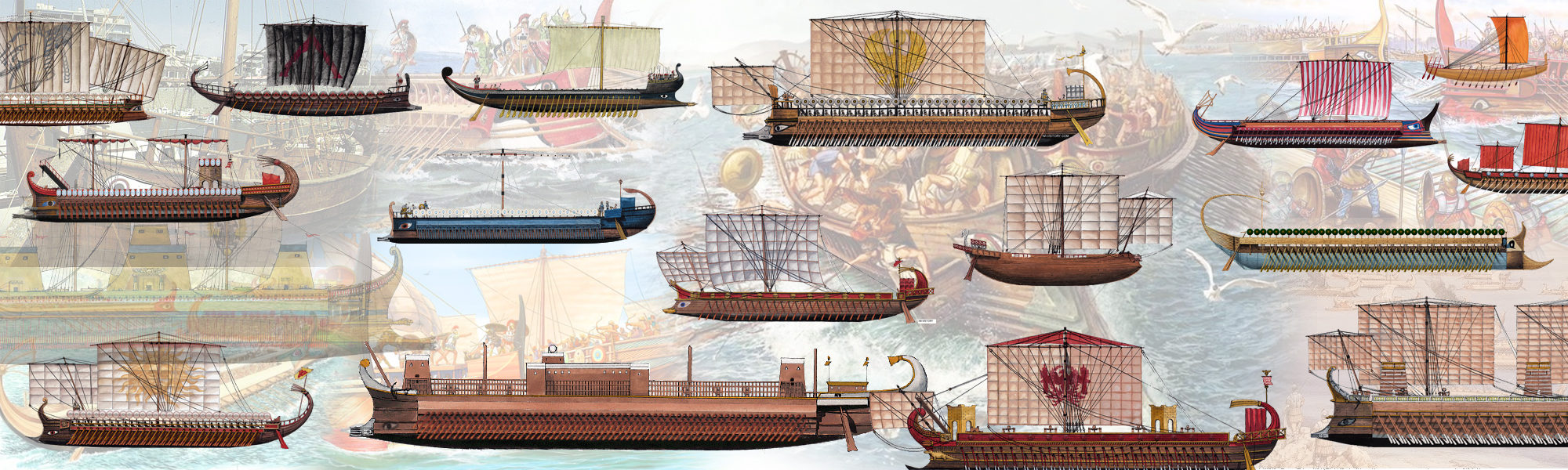

The main shipbuilding materials were fir and pine. The types

of warships used in the Punic Wars – the trireme, quadrireme, quinquereme and

six, as well as the pentecontor and other smaller vessels – were the result of

centuries of development in Mediterranean shipbuilding. Advances in naval

design had been made in the eastern and western Mediterranean and they were

quickly adopted by other states around the coast. There were significant

differences between the fleets of the various cities as each city commissioned

ships according to the fighting force it needed and could afford. Cities

constructed their own versions of the main types of ships – for instance, there

were several different types of trireme.

The earliest evidence that has come down to us about

warships is in the Iliad. Homer describes how the Greeks used their oared

warships – longships – to transport men and their equipment to the battlefield.

In this period oarsmen sat on one level and each one pulled an oar. The ships

were triacontors with thirty oars and pentecontors with fifty oars. At the end

of the eighth century BC, however, as naval tactics changed and ramming became

more important, a two-level arrangement of the oarsmen was introduced. By using

the same number of oarsmen but on two levels, one above the other, the ships

could be made shorter which increased the power, speed and agility that were

needed when ramming. Pentecontors were used not only for war but for commerce

and piracy as well. Specially constructed harbours were not needed for the

ships of this period: they used natural landing places along the coasts, where

they could be pulled onto shore to dry out after a voyage.

In these archaic societies, pentecontors were not built and

maintained solely by the states, as in these archaic societies, pentecontors

were not built and maintained solely by the states, as was the case later on

with the more expensive triremes. Aristocrats owned ships and used them for

various purposes. There was a horizontal social mobility of aristocratic

families and individuals throughout the Mediterranean world. The Greek nobility

used ships in war and diplomacy, to visit religious festivals and games, and

they travelled abroad to keep up personal contacts with the leading families in

other states. Similarly, the Carthaginians used ships to maintain contact with

influential families in the Punic colonies as well as in Greek Sicily and

Etruria, and the Etruscans were involved in trade and piracy. At the time, this

activity was not regarded as dishonourable. Plundering was seen as one way to

acquire wealth and status and so ships were used for piracy when the

opportunity arose. The label ‘pirate’ was applied to an enemy to discredit him.

Perhaps this explains why Etruscan and Tyrrhenian pirates are a common motif in

Greek archaic literature and art and yet the Greeks probably behaved in a

similar way at sea.

The next step in ship development was the trireme, in which

oarsmen were located on three levels on each side of the ship. The new design

was probably introduced at Sidon and Corinth at the end of the eighth century

and the first part of the seventh century BC. The trireme was clearly a more

powerful weapon than its predecessor but it was expensive to build and operate

so only the wealthiest states could afford them. The pentecontor required fifty

oarsmen and ten to twenty additional crew members and soldiers, while a trireme

required a crew of about 210. As a result, triremes were adopted slowly and at

different times by Mediterranean states. So, during the Persian Wars (490–479),

while the trireme was the commonest type of ship, other types were still

deployed – pentecontors continued to be operated in the sixth century BC and

even later. However, by the beginning of the fifth century BC, the trireme had

become the principal tool for projecting power in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Carthaginians probably adopted triremes soon after they were invented and

the Romans introduced them to their fleet in 311, when the offices of the

duoviri navales – naval commissioners in charge of equipping and refitting the

fleet – were introduced. While the wealthier states developed ever more

sophisticated ships, triremes, pentecontors and triacontors continued to serve

in the navies of the smaller states; for example, pentecontors were still

deployed in the third century BC and triacontors in the second century BC.

The development of new types of ship had so far been

concentrated in the eastern Mediterranean. In the fourth century BC, however,

the focus shifted to the west, where the introduction of the quadrireme, the

quinquereme and the six took place. This was the result of naval competition

between Carthage and Syracuse that, together with Athens, were the major

maritime cities of their time. Pliny states that, according to Aristotle, the

Carthaginians invented the quadrireme. According to Diodorus, Dionysius

invented the quinquereme. He probably also built sixes. These innovations in

ship design and construction should be seen against the background of how the

Greek colonists sought to put themselves on the map of a history shared with

the old homeland. The Sicilians and especially the Syracusans sought to gain

influence in the Greek world by making it clear that they were sharing the

burden of fighting the barbarians. This attitude is revealed in the tendency of

Greek texts to represent the battles against the barbarians in the east and

west as happening in a synchronized manner: for example, Himera and Salamis in

Herodotus; Pindar mentioning the battles of Salamis, Plataea and Himera as the

crowing glory of the Athenians, Spartans and Syracusans respectively; and

Timaeus highlighting the connection between Himera and Thermopylae. In effect,

these authors were seeking to show that the west is superior to the east when

it comes to fighting the barbarians. In this case, the leading role in

shipbuilding and innovation in ship design had shifted to Syracuse, to the new

Greek world, and these new vessels were used in their campaign against the

barbarians, the Carthaginians. The new types of ship were quickly adopted by

the navies in the east – quadriremes were in use at Sidon in 351 BC, and the

Cypriot kings who came to support Alexander after the Battle of Issus in 333

had quinqueremes. In the fleet of the city of Tyre, which Alexander besieged,

there were quadriremes and quinqueremes, and Alexander’s own fleet had both

these types of ship. In Athens, quadriremes and quinqueremes are recorded in

the naval lists starting from 330. According to Polybius, the Romans first

introduced quadriremes, quinqueremes and sixes at the beginning of the First

Punic War.

A quinquereme needed a crew of around 350. The aim with the

new types of ship was to target the increasing problem of finding skilful

oarsmen. In a trireme only one man sat to an oar, whereas in the ships of the

higher denominations more than one man sat to an oar, thus only one skilled

rower was needed for each oar-gang, the rest of the rowers being there for

power. In a quadrireme, the oarsmen were probably located on two levels, with

two men pulling each oar. In a quinquereme, the oarsmen were arranged on three

levels, with the top and middle levels manned by two men pulling an oar.

All these warships were designed to operate using the same

tactics as had been devised for triremes. They could be used to ram, in which

case the agility and speed of the ship were important as the aim was to stop

the enemy ship or to damage its oars so that it was immobilized and could

easily be put out of action. Warships could also be used as platforms for

hand-to-hand fighting and launching missiles, and soldiers, archers and

javelin-throwers were included in the crews. Warships that were intended to be

employed in this fashion required a more solid superstructure to accommodate

the large number of fighting men and the hulls were modified to ensure greater

stability. In consequence, such ships tended to be slow and less manoeuvrable.

Various ramming tactics were used. The diekplous or

breakthrough was an operation in which ships were arranged in a column in front

of the enemy. They then tried to break through the enemy line and, by using the

ram, damage the hulls and oars of the enemy ships. The defensive tactic against

a diekplous attack was to keep the ships close together, side by side, so that

it was difficult for the attackers to find space between them. Alternatively,

ships could be arranged in a two-line formation; the ships in the second line

were positioned in order to stop any enemy ships that penetrated the first

line. This method was used at the Battle of Ebro in 217 when the Romans,

together with the Massilians, defeated a Punic fleet. Obviously, this tactic

put the attackers at great risk as their ships might be rammed or lose their

oars and become immobile, which would make them easy targets. In the manoeuvre

known as periplous, attackers attempted to sail around the flank of the enemy

ships so as to come at them from the rear. Diekplous and periplous tactics

could only be carried out by well-trained and well-organized fleets and both

types of tactic can be seen in operation in the battles of the First and Second

Punic Wars.

Sails were used when possible, although rowing was

considered to be faster – the average speed of a ship under oar was 7 or 8

knots. There are no surviving representations of how a trireme under sail

appeared. Naval inventories, however, indicate that there were two masts on a

ship. The main mast was probably located in the middle of the ship and another

smaller mast at the front of the ship was probably raked and stepped forward.

The sails were almost certainly rectangular. Battles always took place near a

coast and, before the fighting started, all unnecessary weight, including the

main mast and rigging, was removed and left on the coast so that the ships were

as light and easy to manoeuvre as possible. During a battle, only oars were

used. When breaking off a battle, the small sail at the front of the ship was

raised on the second mast. As with battles on land, one side could refuse to

engage. However, if the commanders chose to fight – or if they could not avoid

it – they had to consider the speed of their fleet compared to that of the

enemy and to decide whether they should adopt offensive or defensive tactics.

If a slow fleet found itself in an unfavourable tactical situation, it might be

forced to attack in order to avoid a certain defeat.

Several factors affected the speed of the ships. They had to

be regularly hauled onto the shore or put into ship-sheds so they could dry

out; if this was not done, their wooden hulls became waterlogged and they

became heavy and slow. Newly-built ships were likely to be faster than the old

and, of course, their speed depended on their design. The speed of the ships

also depended on the strength of the oarsmen; rowing was exhausting work and

rowers could be expected to do it for only a few hours a day. Sometimes actions

were interrupted so that the crews could rest and the fighting then resumed the

following day.

Standardized shipbuilding was used. The rival states of the

Mediterranean borrowed shipbuilding designs and innovations from each other.

For example, Polybius records that at the beginning of the First Punic War the

Romans used as their model a Carthaginian ship that they had captured when it

ran aground. The Romans were not completely unaware of how to build such a ship

– Polybius exaggerates their ignorance – but they were keen to see the latest

development in Carthaginian shipbuilding. The main Roman contribution to

warfare at sea in this period was the corvus, the boarding-bridge, which they

used to attack enemy ships in the First Punic War. This innovation is

characteristic of the Hellenistic period in which the armies and navies knew

their opponents well and were evenly matched. In these circumstances they were

eager to come up with a new weapon or tactic that would give them an advantage.

This kind of development is particularly visible in the armies and navies

operated by the successors of Alexander the Great.

Alexander’s successors competed for supremacy in the eastern

Mediterranean and, in the arms race that followed, built ships of even greater

denomination. The names of these ships are puzzling. In the literature they are

described as the ‘seven’, the ‘eight’, the ‘nine’ and so on – all the way up to

the ‘forty’. We do not know how they were constructed or how the oarsmen in

them were arranged but big ships were a fleet phenomenon: they were used for

ramming and needed the support of smaller vessels in the navy, which protected

the larger ships. A large number of armed soldiers would have been aboard.

Ships of these types were not used in the Punic Wars, except for a Carthaginian

seven which had been captured from Pyrrhus.

Carthaginian Naval Power

The period of Carthaginian naval power spanned the sixth to

third centuries (with some minor activity in the second) bce. It was a period

of technological evolution, beginning with penteconters and the developments of

the trireme in the sixth century, `fours’ and `fives’ in the fourth century,

and, at the end of that century, `sixes’ and `sevens’, although the

Carthaginians appear to have resisted the gigantism of contemporary Hellenistic

fleets, and to have not gone in much for ships larger than the `five’. Other

ships were used; the Marsala wrecks might have been of hemiola (`one and a half

‘) design, or perhaps were fast transport ships. This might not preclude their

temporary use as com- bat craft. Some transports could be fitted with temporary

rams, as it appears the Marsala wrecks were. Our understanding of the types of

craft in use is hindered by the terminology employed by our sources and our

general ignorance of the concepts underlying the classification of polyremes.

It is likely that our literary sources employed shorthand terms that masked the

true complexity of the make-up of fleets and obscured the diversity of ships,

or indeed ship-designs within such a class as the `five’ (penteres,

quinquireme). However, it seems clear that fleets were often a mixture of quality,

design and size. The force left by Hannibal in Spain in 218 bce (Polyb. 3.3.14)

contained fifty `fives,’ two `fours’ and five `threes.’ The Carthaginian fleet

during the `Truceless War’ consisted of triremes, penteconters and the largest

of their skiffs (akatia) (Polyb. 1.73.2), perhaps because the potential for

enemy action at sea was limited and did not warrant the launch of those `fives’

that had survived the Roman triumph at the Aegates in 241 bce, perhaps also

because the cost of manning them was prohibitive for the cash-strapped repub-

lic. According to Livy (30.43), 500 oar-powered ships “of all types”

were towed out to sea and burned by Scipio at the end of the Second Punic war.

Warships, transports and merchantmen might sail together: Diodorus (14.59.7)

mentions transports (olkades) and “ships with rams” (chalkemboloi)

present at the battle of Catana, while Livy (25.27) reports that Bomilcar

sailed for Syracuse in 212 bce with 130 warships and 700 transports.