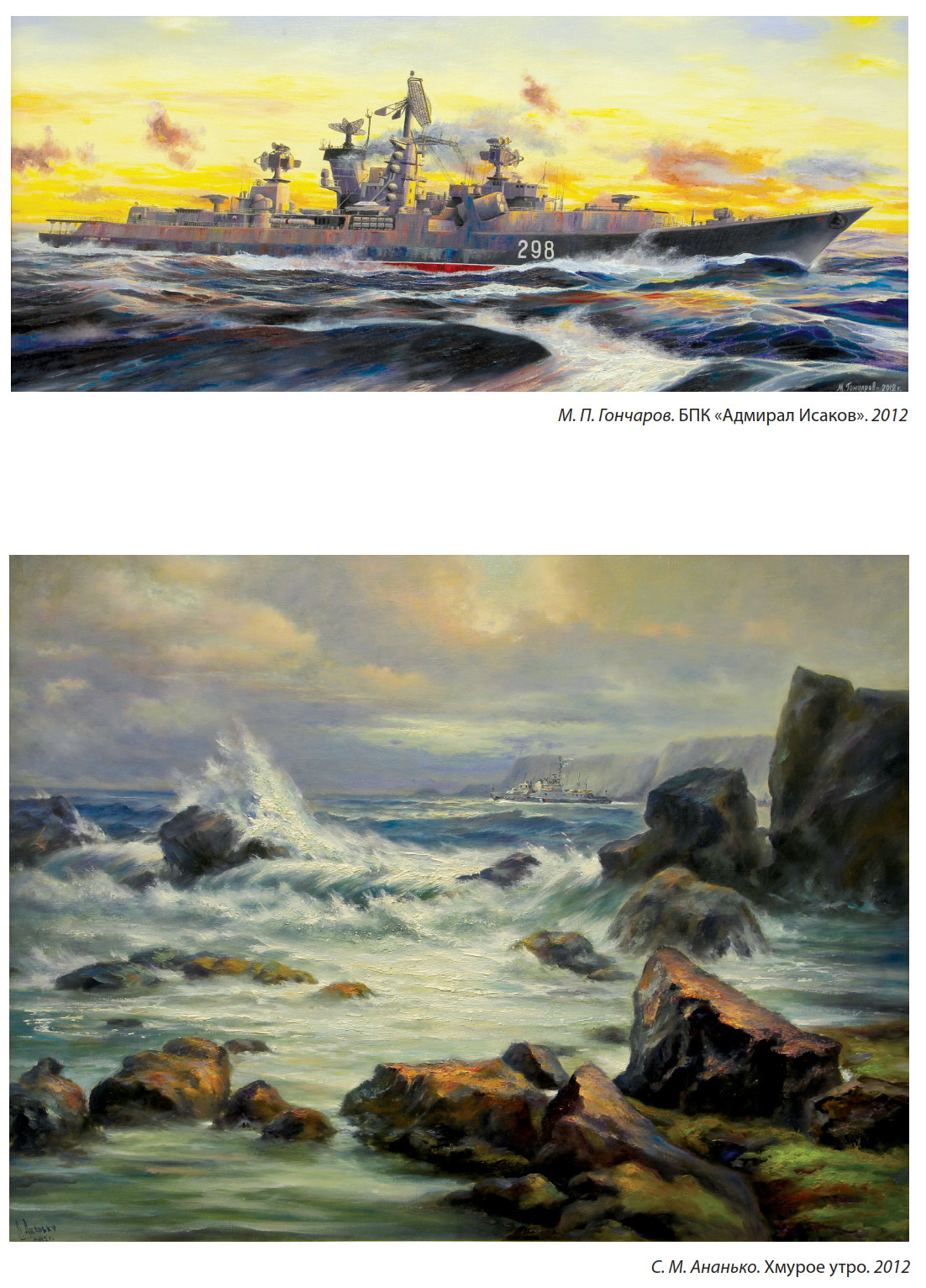

Top: M.P. Goncharov. BOD Admiral Isakov. 2012 Bottom: S.

M. Ananko. Gloomy morning. 2012

Top: S. M. Ananko. TAVKR “Admiral of the Fleet of

the Soviet Union Kuznetsov” while practicing combat training tasks at sea.

2016 Bottom: S. M. Ananko. The heavy nuclear missile cruiser Peter the Great.

2016

SOVIET NAVY WWII

Popularly known in the West as the “Red Fleet,” the Soviet

Navy was divided by geography and ship and base disposition into the Baltic

Fleet, Black Sea Fleet, and Pacific Fleet. It suffered a bloody purge in 1930,

and was intermittently purged by Joseph Stalin after that. From 1935 Stalin

ended debate over whether the Soviet Navy should deploy as a “Jeune École”

fleet equipped only for “small wars” or deploy as a “Mahanian” blue water

battlefleet that sought “command of the sea.” He chose the latter and

thereafter launched a shipbuilding program that centered on battleships, heavy

cruisers, and other large capital warships. Stalin insisted on building

battlecruisers as well, a ship type for which he exhibited a pronounced

preference against all professional advice. The purpose of the big ships was to

gain mastery of the sea around the northern coastlines of the Soviet Union: on

the Gulf of Finland, Baltic Sea, and Sea of Japan. That essentially clear,

rational, traditional naval outlook was complicated by personal quirks and

oddities of the views and personality of Stalin. Most important among his

direct interventions was refusal to build aircraft carriers, a decision that

reflected his limited understanding of how navies projected power.

Stalin at first looked to the United States for assistance

in building a blue water fleet of battleships and battlecruisers. His request

to commission a U.S. shipyard to build a battleship for the Soviet Navy was

spurned. Stalin turned next to Adolf Hitler for technical aid, from the end of

their partnership in conquering Poland in 1939 to the start of Hitler’s

BARBAROSSA invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Stalin paid Hitler back

by extending operational cooperation to the Kriegsmarine in its war with the

Western Allies. A special naval base was set up for the Germans at Lista Bay

near Murmansk that was used by the Kriegsmarine to facilitate the WESERÜBUNG

invasion of Norway in April 1940, while several other Soviet ports were opened

to German warships. The Soviets also aided transfer of a German auxiliary

cruiser around Siberia to prey on Allied shipping in the northern Pacific. For

this assistance the Kriegsmarine provided Moscow specialized naval equipment,

ship schematics, and a partially completed cruiser in a form of barter

exchange. This odd situation reflected Stalin’s long-term view of the need to

build up Soviet naval power and misreading of the German Führer’s intentions.

Stalin’s view contrasted sharply with Hitler’s belief that any short-term naval

aid to Moscow would prove irrelevant once he unleashed his armored legions in

the east.

The Baltic Red Banner fleet began the war with just two

World War I–era battleships and two cruisers. These remained confined to the

base at Kronstadt. It also had 19 destroyers and 65 submarines of varying

quality, as well as a fleet air arm of over 650 planes. During the

Finnish–Soviet War (1939–1940) the Baltic fleet moved to cut off Finland from

sea lanes to Sweden, but no naval engagements ensued with Finnish surface

ships. That changed with BARBAROSSA, as the Kriegsmarine joined the fight in

the Baltic. The Germans moved dozens of minelayers, minesweepers, and other

coastal warships to Finland before June 1941, and afterward established a major

base in the port of Helsinki. Most naval action in the early part of the

German–Soviet war in the Baltic was confined to laying sea mines, sweeping for

mines, U-boat attacks, and aerial attacks by the Luftwaffe on exposed Soviet

ships. There were several small Soviet and German amphibious clashes over a

number of small islands. The major Soviet warship and transport losses came in

August in one of the least known, although the worst, convoy actions of the

entire war. The Soviets sought to relocate smaller warships from Tallinn to

Kronstadt and to evacuate as many personnel by ship as they could before the

Panzers arrived in the Estonian capital. In the German attack on the hastily

formed Soviet convoy the Soviet Navy lost 18 small warships and 42 merchantmen

and troopships, most to a night encounter with a dense minefield. The following

day, as all major warships fled the convoy, Luftwaffe dive bombers struck

floundering and exposed troopships and transports. Only two survived. Total

loss of life was at least 12,000.

The naval garrison on Kronstadt held out for 28 months

during the siege of Leningrad, then used its big guns to support the Red Army

in the operation that finally broke the siege in January–February, 1944.

Meanwhile, in 1942 the Soviet Navy went on the offense in the Baltic. It sent

submarines deeper into the sea, where they enjoyed some success against German

and Finnish shipping plying trade routes from Sweden and along the coastline of

Germany. Several Swedish ships were sunk inadvertently, which moved the Swedish

Navy to introduce a convoy system and on occasion to depth charge Soviet boats.

The most successful Soviet naval operation in the Baltic was an amphibious lift

of nearly 45,000 troops to Oranienbaum in 1944, during the offensive that

lifted the siege of Leningrad. An even larger set of amphibious operations

landed Red Army soldiers and Soviet Navy marines on a number of small, but key,

islands in the Gulf of Riga in late 1944. The situation in the air was also

reversed by 1944, as Red Army Air Force and Soviet Navy planes harassed and

sank congested German shipping. From 1941 to 1945 the Soviet Baltic fleet lost

one old battleship (to bombs), 15 destroyers, 39 submarines, and well over 100

minesweepers, smaller warships, and transports, as well as numerous landing

craft. A modern battleship under construction before the war was locked in port

by the siege of Leningrad and never completed.

The war began disastrously for the Soviet Navy’s Black Sea

Fleet, which was bombed at anchor on the first day, June 22, 1941. Before that

attack the Black Sea Fleet comprised a single modernized dreadnought, four

cruisers, dozens of older and new destroyers, 47 old submarines, nearly 90

motor torpedo boats, and sundry coastal craft. It had 626 aircraft, mostly of

obsolete types. The Black Sea Fleet was also responsible for the Caspian Sea,

the Sea of Azov, and patrolling the lower Don and Volga Rivers. A 59,000 ton

giant super battleship, the “Sovetskaia Ukraina,” was still under construction

when the bombs started to fall, just like its sister ship in Leningrad. When

Army Group South took the port of Nikolaev during the Donbass-Rostov operation,

the “Sovetskaia Ukraina” was captured. Once the terrible siege of Sebastopol

began, the Fleet’s main port was closed to naval operations and ships scrambled

to relocate to ports farther east. The first Black Sea Fleet amphibious

operation was a landing of 2,000 marines behind Rumanian lines near Odessa, a

desperate action that failed to save the city. Instead, between October 1–16,

1941, an evacuation of over 86,000 soldiers and 14,000 other Soviet citizens

was carried out from Odessa. The Fleet facilitated large-scale amphibious

landings at Kerch-Feodosiia in December 1941. Without effective Kriegsmarine

opposition in the Black Sea, the Soviets took the Germans in the Crimea by

surprise. They came ashore in force, over 40,000 strong, at more than two dozen

locations behind the main enemy force, which was investing Sebastopol. More

troops were sent in via an ice road over the Kerch Straits. A larger amphibious

and airborne operation was planned to retake the entire Crimean peninsula in

January 1942, but it was canceled when the situation badly deteriorated. When

the Germans assaulted in May with their main force, relocated from Sebastopol,

the Soviet Navy evacuated survivors across the Kerch Straits.

All this time, the Black Sea Fleet maintained a 240-mile

lifeline into Sebastopol under constant and heavy Luftwaffe attack. By late

1942 the Fleet faced German and Italian small craft flotillas that were shipped

overland and reassembled in the Crimea. The Soviets also faced at least six

Axis submarines in the Black Sea, including one from Rumania. In February 1943,

the Soviets carried out two amphibious landings around Novorossisk. The smaller

landing established a beachhead that held on, and was successfully reinforced

by sea. On September 10 the port fell when Black Sea Fleet leaders used over

130 small boats to enter and assault the harbor. However, in October the Fleet

lost three new destroyers to land-based bombers, after which Stalin forbade its

commanders to expose any surface ships to danger. More landings were made in

German rear areas to block the Wehrmacht on its long retreat out of the east.

These were mostly wasteful of Soviet lives and forces. Worst of all, the Soviet

Navy failed to prevent evacuation of over 250,000 Axis troops of Army Group A

across the Kerch Straits during September–October, 1943. That was mostly

Stalin’s fault: he refused to expose any large surface ships to German bombing,

lest they be lost. That lessened the victory at Sebastopol achieved by Soviet

ground forces in May 1944: a flotilla of small ships and barges was massively

bombed and shelled, but 130,000 German and Rumanians escaped who could have

been stopped by the big guns of destroyers, cruisers, and the Fleet’s unopposed

dreadnought that Stalin would not allow into action.

Pacific Fleet operations were minimal and strictly defensive

until the Manchurian offensive operation (August 1945). Most submarines were

therefore released for service in the North Sea. To get there, they made a

remarkable voyage across the Pacific, down the coast of North America, through

the Panama Canal, and across the Atlantic to Murmansk or Archangel. Not all

survived the journey. Those that did took up duty scouting for and protecting

arctic convoys from Britain. In September 1943, the Soviet Navy was denied any

ships surrendered by the Regia Marina to the Royal Navy at Malta. They went to

the British instead. The Soviets did acquire a number of German surface ships

in late May 1945, along with a share in those U-boats that were scuttled by

their captains or sunk by the Western Allies.

Soviet Navy – Post WWII

In the immediate post-war years the only naval units of even

marginal significance were three battleships: a Russian vessel dating back to

tsarist times and two British ships of First World War vintage, which had been

lent to the USSR during the war. One of the latter was returned to the UK in

1949, having been replaced by the ex-Italian Giulio Cesare, which the Soviets

renamed Novorossiysk.fn3 There were also some fifteen cruisers – a mixture of

elderly Soviet designs, nine modern Soviet-built ships, a US ship lent during

the war (and returned in 1949), and two former Axis cruisers, one ex-German,

the other ex-Italian. There was also a force of some eighty destroyers, also of

varying vintages and origins.

During the 1940s and 1950s these Soviet warships were rarely

seen on the high seas, apart from a limited number of transfers between the

Northern and Baltic fleets, which tended to be conducted with great rapidity.

The only exception was a series of international visits, mainly by the

impressive Sverdlov-class cruisers, which were paid to countries such as Sweden

and the UK. The navy suffered a major setback in 1955 when the battleship Novorossiysk

was sunk while at anchor in the Black Sea by a Second World War German ground

mine, an event which led to the sacking of the commander-in-chief, Admiral N.

M. Kuznetzov; he was replaced by Admiral Gorshkov.

In the early 1960s, however, individual Soviet units began

to be seen more frequently in foreign waters, as did ever-increasing numbers of

‘intelligence collectors’, laden with electronic-warfare equipment. These

ships, generally known by their NATO designation as ‘AGIs’, monitored US and

NATO exercises and ship movements. The original AGIs were converted trawlers

and salvage tugs, but, as the Cold War progressed and the Soviet navy became

increasingly sophisticated, larger and more specialized ships were built,

culminating in the 5,000 tonne Bal’zam class, built in the 1980s. In addition

to such ships, conventional warships regularly carried out intelligence-collecting

and surveillance tasks, particularly when Western exercises were being held.

Apart from general eavesdropping on Western communications links and studying

the latest weapons, such missions helped the Soviet navy to learn about US and

NATO tactics, manoeuvring and ship-handling.

The Soviets also put considerable effort into espionage

(human intelligence, or HUMINT, in intelligence jargon) against Western navies.

This included the Kroger ring in the UK, which was principally targeted against

British anti-submarine-warfare facilities, and the Walker spy ring in the USA,

which gave away a vast amount of information on US submarine capabilities and

deployment.

The growth and increasing ambitions of the Soviet navy were

best illustrated by the size, scope and duration of its exercises. The first

important out-of-area exercise was held in 1961, when two groups of ships – one

moving from the Baltic to the Kola Inlet and the other in the opposite

direction (a total of eight surface warships, four submarines and associated

support ships) – met in the Norwegian Sea. There they conducted a short

exercise before continuing to their respective destinations.

In early July 1962 transfers between the Baltic and Northern

fleets again took place, coupled with the first major transfer from the Black

Sea Fleet to the Northern Fleet. This was followed by a much larger exercise,

extending from the Iceland–Faroes gap to the North Cape, which included surface

combatants, submarines, auxiliaries and a large number of land-based naval

aircraft. The activity level increased yet again in 1963, and the major 1964

exercise involved ships moving through the Iceland–Faroes gap for the first

time, while units of the Mediterranean Squadron undertook a cruise to Cuba. By

1966 exercises were taking place in the Faroes–UK gap and off north-east

Scotland (both long-standing preserves of the British navy) and also off the

coast of Iceland.

In 1967 the naval highlight of the Arab–Israeli Six-Day War

was the dramatic sinking of the Israeli destroyer Eilat by the Egyptian navy

using Soviet SS-N-2 (‘Styx’) missiles launched from a Soviet-built Komar-class

patrol boat. Not surprisingly, Soviet naval prestige in the Middle East was

high, and the Soviets took the opportunity to enhance it yet further by port

visits to Syria, Egypt, Yugoslavia and Algeria, employing ships of the Black

Sea Fleet.

The following year saw the largest naval exercise to date;

nicknamed Sever (= North) it involved a large number of surface ships,

land-based aircraft, submarines and auxiliaries. The exercise covered a variety

of areas, but the main activity took place in waters between Iceland and

Norway. One of the naval highlights of the year, for both the Soviet and the

NATO navies, was the arrival in the Mediterranean of the first Soviet

helicopter carrier, Moskva.

Further exercises and deployments took place in 1969, but in

the following year Okean 70 proved to be the most ambitious Soviet naval

exercise ever staged. This involved the Northern, Baltic and Pacific fleets and

the Mediterranean Squadron in simultaneous operations, with the major emphasis

in the Atlantic. A large northern force, comprising some twenty-six ships,

started with anti-submarine exercises off northern Norway between 13 and 18

April, and then proceeded through the Iceland–Faroes gap to an area due west of

Scotland, where it carried out an ‘encounter exercise’ against units from the

Mediterranean Squadron. The two groups then sailed in company to join the

waiting support group, where a major replenishment at sea took place. Other

facets of the exercise included units of the Baltic Fleet sailing through the

Skaggerak to operate off south-west Norway, and an amphibious landing exercise

involving units of the recently raised Naval Infantry coming ashore on the

Soviet side of the Norwegian–Soviet border.

This was a very large and ambitious exercise, from which the

Soviet navy learned many major lessons, one of the most important of which was

the falsity of the concept of commanding naval forces at sea from a shore

headquarters. Such a concept had been propagated for two reasons: first,

because it complied with the general Communist idea of highly centralized power

and, second, because it also avoided the complexity and expense of flagships.

Once Okean 70 had proved this concept to be impracticable, ‘flag’ facilities

were built into the larger ships, although the Baltic Fleet continued to be

commanded from ashore.

The exercise which took place in June 1971 rehearsed a

different scenario, with a group of Soviet Northern Fleet ships sailing down

into Icelandic waters, where they reversed course and then advanced towards Jan

Mayen Island to act as a simulated NATO carrier task group, which was then

attacked by the main ‘players’. Again, a concurrent amphibious landing formed

part of the exercise.

There were no major naval exercises in 1972, but in a spring

1973 exercise Soviet submarines practised countering a simulated Western task

force sailing through the Iceland–UK gap to reinforce NATO’s Northern flank,

while a similar exercise in 1974 took place in areas to the east and north of

Iceland. Okean 75 was an extremely large maritime exercise, involving well over

200 ships and submarines together with large numbers of aircraft. The exercise

was global in scale, with specific exercise areas including the Norwegian Sea,

where simulated convoys were attacked; the northern and central Atlantic,

particularly off the west coast of Ireland; the Baltic and Mediterranean seas;

and the Indian and Pacific oceans. Overall, the exercise practised all phases

of contemporary naval warfare, including the deployment and protection of

SSBNs.

In 1976 an exercise started with a concentration of warships

in the North Sea, following which they transited through the Skagerrak and into

the Baltic. Although not an exercise as such, great excitement was caused among

Western navies when the new aircraft carrier Kiev left the Black Sea and sailed

through the Mediterranean before heading northward in a large arc, passing

through the Iceland–Faroes gap and thence to Murmansk. NATO ships followed this

transit very closely, as it gave them their first opportunity to see this large

ship and its V/STOL aircraft.

The following year saw two exercises in European waters, the

first of which was held in the area of the North Cape and the central Norwegian

Sea. The second was much larger and consisted of two elements, one involving

the Northern Fleet in the Barents Sea, while in the other ships sailed from the

Baltic, north around the British Isles and then into the central Atlantic. Also

in 1977 the Soviet navy suffered the second of its major peacetime surface

disasters when the Kashin-class destroyer Orel (formerly Otvazhny) suffered a

major explosion while in the Black Sea, followed by a fire which raged for five

hours before the ship sank, taking virtually the entire crew to their deaths.

In 1978 the passage of another Kiev-class carrier enabled an

air–sea exercise to take place to the south of the Iceland–Faroes gap. Similar

exercises followed in 1979 and 1980. The 1981 exercise involved three groups

and took place in the northern part of the Barents Sea.

There were no major naval exercises in 1982, but the

following year saw the most ambitious global exercise yet, with concurrent and

closely related activities in all the world’s oceans, involving not only

warships, but also merchant and fishing vessels. In European waters, three

aggressor groups assembled off southern Norway and then sailed northward to

simulate an advancing NATO force; they were then intercepted and attacked by

the major part of the Northern Fleet.

The major exercise in 1985 followed a similar pattern, with

aggressor groups sailing northeastward off the Norwegian coast, to be attacked

by a large Soviet defending task group which included Kirov, the lead-ship of a

new class of battlecruiser, Sovremenny-class anti-surface destroyers and

Udaloy-class anti-submarine destroyers, as well as many older ships. There was

also substantial air activity, which included the use of Tu-26 Backfire

bombers. Although not apparent at the time, this proved to be the zenith of

Soviet naval activity, and in the remaining years of the Cold War the number

and scale of the exercises steadily diminished.

These major exercises enabled the Soviet navy to rehearse

its war plans and to demonstrate its increasing capability to other navies,

particularly those in NATO. There were, of course, many smaller exercises, such

as those involving amphibious capabilities, which took place on the northern

shores of the Kola Peninsula, on the Baltic coast and in the Black Sea. It is

noteworthy, however, that the vast majority of the exercises held in European

waters, and particularly those held from 1978 onwards, while tactically

offensive, were actually strategically defensive in nature, involving the

Northern Fleet in defending the north Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea and the

area around Jan Mayen Island.

Soviet at-sea time was considerably less than that of the US

and other major Western navies. The latter maintained about one-third of their

ships at sea at all times, while only about 15 per cent of the Soviet navy was

at sea, reducing to 10 per cent for submarines. The Soviets did, however,

partially offset this by placing strong emphasis on a high degree of readiness

in port and on the ability to get to sea quickly.

Modern Russian Federation Navy

The 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union led to a severe

decline in the Russian Navy. Defense expenditures were severely reduced. Many

ships were scrapped or laid up as accommodation ships at naval bases, and the

building program was essentially stopped. Sergey Gorshkov’s buildup during the

Soviet period had emphasised ships over support facilities, but Gorshkov had

also retained ships in service beyond their effective lifetimes, so a reduction

had been inevitable in any event. The situation was exacerbated by the

impractical range of vessel types which the Soviet military-industrial complex,

with the support of the leadership, had forced on the navy—taking modifications

into account, the Soviet Navy in the mid-1980s had nearly 250 different classes

of ship. The Kiev class aircraft carrying cruisers and many other ships were

prematurely retired, and the incomplete second Admiral Kuznetsov class aircraft

carrier Varyag was eventually sold to the People’s Republic of China by

Ukraine. Funds were only allocated for the completion of ships ordered prior to

the collapse of the USSR, as well as for refits and repairs on fleet ships

taken out of service since. However, the construction times for these ships

tended to stretch out extensively: in 2003 it was reported that the Akula-class

submarine Nerpa had been under construction for fifteen years. Storage of

decommissioned nuclear submarines in ports near Murmansk became a significant

issue, with the Bellona Foundation reporting details of lowered readiness.

Naval support bases outside Russia, such as Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam, were

gradually closed, with the exception of the modest technical support base in

Tartus, Syria to support ships deployed to the Mediterranean. Naval Aviation

declined as well from its height as Soviet Naval Aviation, dropping from an

estimated 60,000 personnel with some 1,100 combat aircraft in 1992 to 35,000

personnel with around 270 combat aircraft in 2006. In 2002, out of 584 naval

aviation crews only 156 were combat ready, and 77 ready for night flying.

Average annual flying time was 21.7 hours, compared to 24 hours in 1999.

Training and readiness also suffered severely. In 1995, only

two missile submarines at a time were being maintained on station, from the

Northern and Pacific Fleets. The decline culminated in the loss of the Oscar

II-class Kursk submarine during the Northern Fleet summer exercise that was

intended to back up the publication of a new naval doctrine. The exercise was to

have culminated with the deployment of the Admiral Kuznetsov task group to the

Mediterranean.

As of February 2008, the Russian Navy had 44 nuclear

submarines with 24 operational; 19 diesel-electric submarines, 16 operational;

and 56 first and second rank surface combatants, 37 operational. Despite this

improvement, the November 2008 accident on board the Akula-class submarine

attack boat Nerpa during sea trials before lease to India represented a concern

for the future.

In 2009, Admiral Popov (Ret.), former commander of the

Russian Northern Fleet, said that the Russian Navy would greatly decline in

combat capabilities by 2015 if the current rate of new ship construction

remained unchanged, due to the retirement of ocean-going ships.

In 2012, President Vladimir Putin announced a plan to build

51 modern ships and 24 submarines by 2020.[32] Of the 24 submarines, 16 will be

nuclear-powered. On 10 January 2013, the Russian Navy finally accepted its

first new Borei class SSBN (Yury Dolgorukiy) for service. A second Borei

(Aleksandr Nevskiy) was undergoing sea trials and entered service on 21

December 2013. A third Borei class boat (Vladimir Monomakh) was launched and

began trials in early 2013, and was commissioned in late 2014.