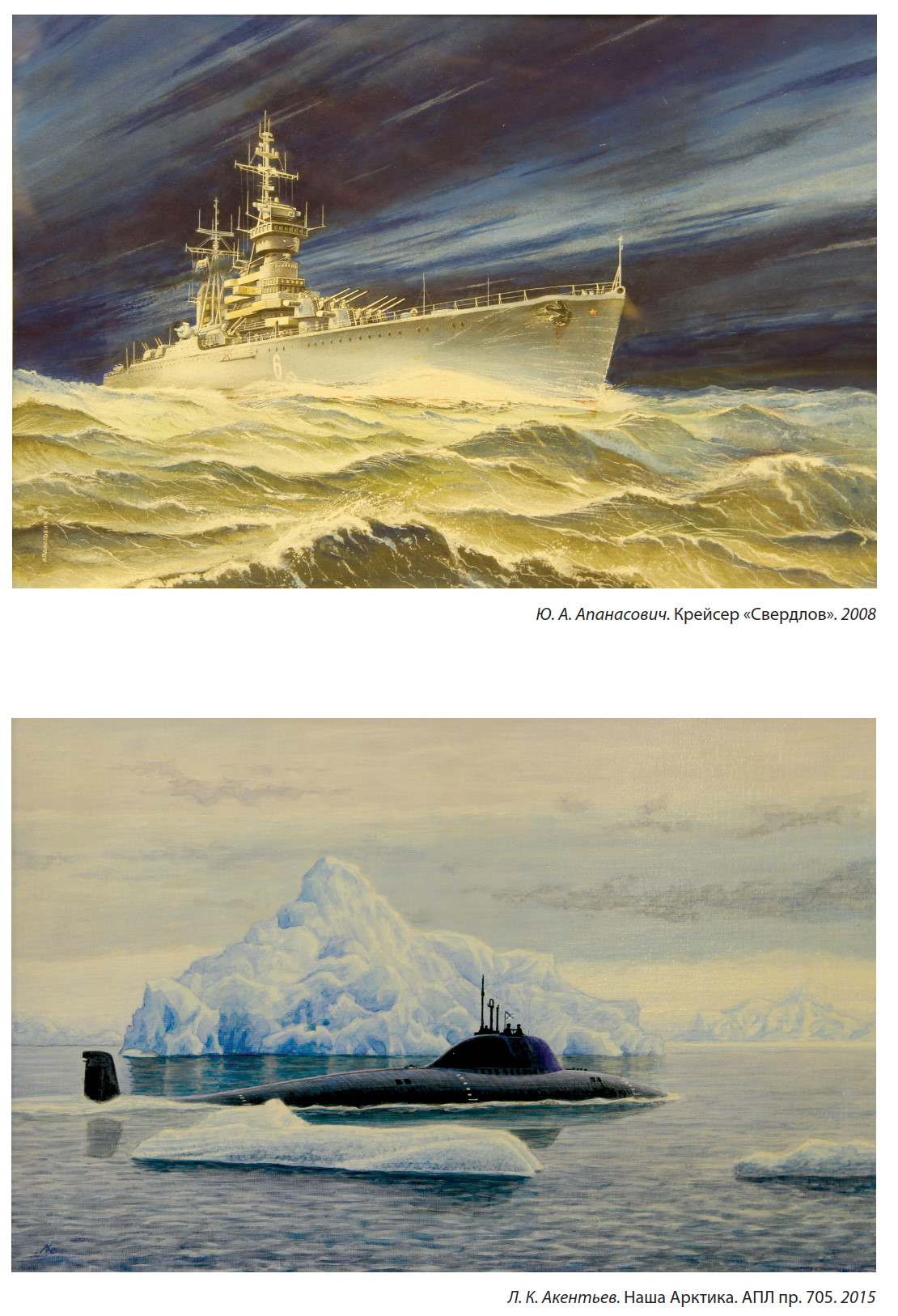

Top: Y.A. Apanasovich. The cruiser Sverdlov. 2008 Bottom:

L.K. Akentiev. Our Arctic. Nuclear Submarine 705. 2015

Top: L.K. Akentiev. “St. Phoca” at Cape

Flora. 2015 Bottom: M.P. Goncharov. Squadron battleship

“Tsesarevich”. 2001

Russian Navy 1695-1900

The Russian Navy was founded by Peter the Great (1682-1725)

in the Baltic to protect Russia from then powerful Sweden and on the Sea of

Azov to counter the Ottoman Empire. Catherine the Great extended Russia’s

control to the Black Sea by adding a fleet based at Sevastopol. Russia

maintained small flotillas on the Caspian and White Seas. By the end of the

eighteenth century there was also a Pacific Squadron that supported the

Russian-American Company colony in Alaska. From Catherine II’s reign until the

late 1820s, periods of friendly relations with Britain allowed the Baltic Fleet

to deploy to the Mediterranean in a series of campaigns against the Ottomans. A

Russian squadron joined an Anglo-French fleet in the victory over Mehmet Ali at

Navarino in 1827. Thereafter until the 1854-56 Crimean War, the Baltic Fleet

declined into the autocrat’s naval parading force. At the same time the

professionalization of the Black Sea developed apace as a result of superior

leadership, notably Admiral M. P. Lazarev, and continuous operations in support

of Russia’s protracted war with Caucasian mountaineers. Nakhimov’s overwhelming

victory against a Turkish Squadron at Sinope in late 1853, which brought

Anglo-French intervention in the Crimean War, was, in fact, a continuation of

the Black Sea Fleet’s mission to isolate the Caucasian theater of operations

from maritime supply.

The 1856 defeat that saw the Black Sea Fleet abolished and

made very clear the need for rail connections to link south Russia with the

Moscow-St. Petersburg core and to avoid a Baltic blockade, also came at the

crucial time when the great steam-and-steel revolution was taking place. This

coincided with the scrapping of the IRN’s sailing ships and their replacement

both by modern warships, such as those which visited the United States in

1863-64, and in a revival of concern with naval strategy and tactics. Though

reduced in size to one thirty-sixth of the million-man army, the 28,000 men in

the navy were much more technically proficient and efficient.

Between the beginning (1696) and the end (1917) of its

history, the Imperial Navy had far more influence than its modest size and

marginal role would suggest. Three key themes emerge. The first concerns the

role of the navy in national strategy; the second the relationship between the

navy and the process of technological modernization and Westernization; and the

third the issue of the professionalization of the officer corps. By the

mid-nineteenth century the latter involved the development of a system of

advanced schooling for officers, the cultivation of a shared vision of the

service through publications for the officer corps (the official and unofficial

sections of Morskoi sbornik), and the unsuccessful resolution of the especially

difficult question of officer advancement (chinoproizvodstvo) which turned on

the conflict between promotion based on bureaucratic seniority or talent and

achievement.

The navies that Peter built on the Sea of Azov and in the

Baltic were fleets in being that, as in the later Soviet case until the 1950s,

had deterrent value, but also served as a “second arm” supporting amphibious

operations against hostile shores, a mission that the Black Sea Fleet also

developed. Given the demands of maintaining a continental army, the navy had

few levers to use to extract bigger budgets. After the early combined

operations under Peter, the navy languished until the reign of Catherine II,

when it once again dominated the Baltic and won command of the Black Sea. In

this period the IRN did venture out of the Baltic and enjoyed some success in

battle. Because of the nature of the final struggle with Napoleon, a

continental war fought in alliance with Britain and as a result of the debt

incurred in prosecuting that war, the navy once again went into decline. The

exception to this being the mounting of scientific expeditions and round-the

world cruises. Russian naval officers came to see such deployments as necessary

for the training of professional naval officers.

The history of the navy from Petrine days to the end of its

second century reflected the patterns and tensions between repressive, militaristic

autocracy and thoughtful, visionary obshchestvo (educated society). The Crimean

War dealt a heavy blow to that structure, challenged its institutions and

stimulated the Great Reforms, which included the emancipation of the serfs as a

basic move toward a more productive economy and the needs of the armed forces.

In this the admiral, General-Admiral Grand Duke Konstantin

Nikolaevieh, played an important role from 1854 in protecting and training five

future ministers in bureaucratic politics and administration and instilling in

them the hope that virtue and talent would triumph. He also cultivated an

alliance with the naval officers who had been proteges of Admiral Lazarev and

brought them into the senior leadership of the navy. With no Black Sea Fleet because

of the demilitarization of the Black Sea, this leadership focused its attention

on the modernization of the Baltic Fleet and the development of a Pacific

Squadron. The visits to the United States in 1863 of Baltic and Pacific

squadrons were part of a new naval strategy that embraced such deployments as a

deterrent threat to British trade.

By the time of the Great Reforms (1856-70) following the

Crimean defeat, the navy was allowed to play a wider role through modernization

so as to help the Russian Army preserve the country’s great-power status. From

1856, then, the Russian Navy developed in parallel with Western naval forces

and created its own industrial base in alliance with private enterprise. This

development rested upon the cultivation of a professional officer corps, where

initiative and experience took precedence over seniority. In 1877-78 the Black

Sea Fleet, which was almost non-existent-remilitarization had only become

possible in 1870 and there were no yards or mills in the South to build modern

ironclads-managed to neutralize a much larger Turkish Navy through the

aggressive use of mines and torpedoes.

Believing that he should, unlike most Russians, consult

affected parties, the grand duke turned Morskoi sbornik (Naval Digest) from a

dull official bulletin into a lively journal of discussions, which helped

clarify the confusions and the liberations of the Great Reforms.

These abolished the ancien regime and introduced a new world

in which local organizations governed what was within their ken. This very much

affected the army deprived of its privileged aristocratic officers and its serf

soldiers. It also touched an increasingly technological steam and steel navy

after 1860. At the same time the implications of the reform process frightened

many conservatives in the Imperial family (notably the heir to the throne, the

future Alexander III, the bureaucracy, and society). Konstantin Nikolaevich was

for them a “red,” a dangerous figure whose ideas could lead to the undermining

of the autocracy itself. After the death of Alexander II, the new tsar moved to

remove the grand duke from his post as general-admiral and other state offices.

With the grand duke’s departure from leadership of the navy,

leadership of the Naval Ministry passed into the hands of men who once again

cultivated appearances at the expense of accomplishments and saw initiative and

experience as grave dangers to institutional stability. The naval counter

reforms, especially the tsenz (promotion based on positions held and time in

service) created a bureaucratized force. The Naval Ministry reverted to the

purchase of major combatants abroad and failed to develop a staff system to

guide the navy in preparation for war. The full implications of this decline

were only revealed by the destruction of the Russian squadron at Port Arthur and

the defeat of Rozhestvennsky’s squadron at Tsushima (1905).

Russian Navy WWI

Peter the Great founded the Russian Navy in the early 1700s.

The main fleet operated in the Baltic Sea with a squadron on the Sea of Azov

which expanded later that century to become the Black Sea Fleet. During the

Crimean War the sailors and guns of the Black Sea Fleet played a distinguished

role in the defence of Sebastopol. However, the Baltic Fleet was reduced to

passivity having proved itself incapable of breaking the Anglo-French blockade.

When the empire expanded eastwards a Pacific Squadron was established with its

base at Vladivostok. The remilitarization of the Black Sea at roughly the same

time led to a further period of expansion but due to limited resources, the

Baltic Fleet was somewhat overlooked. However, pressure from France following

the 1894 treaty led to an increase in the strength of the Baltic Fleet to

counter the growing naval power of Germany. As a result French companies

received ship-building orders as Russian heavy industry did not have the

capacity to build complete, modern warships.

The Russo-Japanese War was a disaster for the Russian Navy

that lost virtually all of the Pacific Squadron as well as much of the Baltic

Fleet which sailed to its doom at the battle of Tsushima. With severely limited

resources the navy was faced with the dilemma of, “we must know what we want”

in terms of ship types and whether it should concentrate on the Pacific Ocean,

the Baltic or Black seas.

1906–1914

Although there had been a Navy Minister for decades his role

was that of junior partner in the War Ministry where the army was regarded as

the more important service. Strategically the navy’s role was to support the

army.

In 1906 a Naval General Staff was established under the new

State Defence Committee but was almost immediately at loggerheads with the Navy

Minister Admiral A. A. Birilov who regarded the new body as an upstart creation

of little value. Both the Navy Ministry and the Naval General Staff produced

plans for modernisation and reform, but neither was acceptable on the grounds

of cost. Furthermore the army and the Council of State Defence objected,

complaining that they exceeded the Navy’s defensive role. As the arguments and

politicking dragged on the Tsar intervened. Nicholas II, in common with his

cousins George V and Wilhelm II, liked ships and wished to expand Russia’s

overseas influence by the possession of a strong, modern navy. However, the

Third Duma (1907–12) preferred to invest the money that was available in the

army. Consequently the annual naval estimates became a matter of prolonged

debate.

A series of emergency grants provided for the replacement of

several ships lost at Tsushima and as money from increased state revenues and

French loans filled the treasury and Turkey began to expand its fleet in the

Black Sea, it was decided to increase the size of the fleet both there and in

the Baltic. While a considerable proportion of this money was invested in capital

projects such as shipyards, dry docks and improved port facilities, a large

ship building programme was also approved. With the appointment of a new Navy

Minister who was more receptive to reform, Admiral I. K. Grigorovich, in 1911

the Duma began to look more favourably on the naval estimates. On 6 July 1912

the Tsar signed a £42,000,000 expansion plan. The problem was that many of the

ships laid down under this programme were not scheduled for completion for some

time. Furthermore they were highly dependent on foreign expertise and

equipment, and the overseas contracts were not placed with Russia’s likely

allies. As with heavy artillery procurement orders were made with German

companies as well as those of Britain and France.

1914

At the outbreak of war two Russian cruisers, paid for and on

the point of completion in German yards, were commissioned into the German

navy. According to the 1914 edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships, four Dreadnoughts

and two cruisers were also under construction for the Baltic Fleet, as were

three Dreadnoughts and nine cruisers for the Black Sea Fleet. These new capital

ships were to be complemented by thirty-six new destroyers and a large number

of submarines and auxiliary vessels. The majority of these ships were due for

completion within the next few years. By 1914 Russian naval expenditure only

lagged behind that of Britain and the USA having overtaken Germany and other

potential enemies. Indeed Russia and Britain were on the point of signing a

naval agreement when the war broke out. But the Russian Navy was not to be

committed offensively during the war years and the majority of its operations

were defensive.

1914–17

As noted in Plan 19 both fleets were subordinated to Stavka.

The HQ of the Black Sea Fleet was at Sebastopol, the headquarters of the Baltic

fleet at Helsingfors (Helsinki) in Finland, having major bases at Kronstadt and

Riga. The Navy Ministry at Petrograd acted as a clearing house for orders from

Stavka.

As the Pacific Squadron took virtually no part in the war it

is mainly the operations of the Baltic and Black sea fleets that concern us

here and as little or no co-ordination was possible each will be dealt with

individually.

Baltic Sea Fleet

At the outbreak of war the Baltic Fleet put a carefully

planned defensive mining programme into operation. Russian mines were reputedly

the best and most effective used by any navy in the war. The objective of this

was to prevent the movement of German naval units against the capital or the

flank of NW Front. The officer in charge of mining was Captain A. V. Kolchak

who was to advance swiftly to the rank of Admiral. The major achievement of the

Baltic Fleet during 1914 was the capture of a set of German naval code books

from the Magdeburg during August thus enabling Allied intelligence officers to

monitor German movements.

For the next two years the Baltic Fleet’s major units were

preserved in anticipation of a decisive fleet action. The burden of offensive

operations was undertaken by the eleven submarines of the Baltic Fleet and a

small number of British submarines that reached Russia via the Arctic or by

running the gauntlet of German patrols at the mouth of the Baltic. Although the

submariners of both navies did sterling work against coastal traders plying the

Baltic, the bulk of the Russian fleet remained in harbour. Such passivity had a

dire effect on the officers and men leaving them prey to apathy and

politicisation. Protected by the increasingly complex web of minefields the

sailors’ discipline eroded slowly. Cruises were limited due to the lack of

British anthracite coal stocks which were in short supply (although

interestingly enough, thousands of tons of coal had in fact been stockpiled at

Archangel and Murmansk but were instead being used to ballast ships returning

to their home ports after delivering munitions to Russia). The sailors’

dockside work was also inhibited by the blanket of ice that built up on the

harbours and the ship building programme was held up because many of the

vessels under construction were designed only to take German-made turbines. The

overall result of all these problems was a number of crews with little or

nothing to do.

When the army’s rifle shortage became critical in 1915 the

navy exchanged its Russian rifles for the Japanese Arisaka to ease ammunition

supply problems. Japan also salvaged ships from the Russo-Japanese War, which

were re-commissioned by the Russians and a Separate Baltic Detachment was

formed but it did not manage to return to the Baltic.

Problems

The first outbreak of trouble occurred on the cruiser

Rossiia in Helsingfors during September 1915. The sailors protested about poor

food, overly harsh discipline and “German officers”. Rumours of the treachery

of the “German officers” had been growing since the loss of the cruiser Pallada

when on patrol duties in November 1914, though the fact that it went down with

all hands did not enter into the gossip mongers’ tales.

The navy seems to have had a greater proportion of officers

with German sounding names than the army and being a smaller service they were

more noticeable. Indeed the commander of the Baltic Fleet in 1915 was Admiral

N. O. von Essen who apparently considered “russifying” his name during this period.

Although the ringleaders aboard the Rossiia were arrested it did not prevent

further problems in November 1915 when part of the crew of the battleship

Gangoot rioted beyond their officers’ control over poor food. More worrying for

senior commanders was the refusal of neighbouring vessel’s crews to train their

guns on the mutineers. Finally the threat of a submarine putting torpedoes into

the Gangoot put a stop to the mutiny. A series of arrests were made resulting

in those men being assigned to disciplinary battalions. Disciplinary

battalions, usually 200 men at a time, were often sent to NW Front until

Twelfth Army complained that they more trouble than they were worth.

Subsequently the disciplinary battalions were detained at the naval bases where

they became progressively more difficult to control.

As 1916 wore on morale declined still further. Whenever

ships changed commanders or officers transferred and attempts were made to

tighten discipline where it was perceived to be too lax the men reacted with

dumb insolence or worked at a snail’s pace. That November Grigorovich expressed

his concerns to the Tsar during an interview at Stavka. However, Nicholas

refused to discuss internal security matters nor did he respond to written

reports on similar matters. The situation was summed up in a report from the

commander of the Kronstadt base to the navy’s representative at Stavka.

“Yesterday I visited the cruiser Diana…I felt as if I were on board an enemy

ship.… In the wardroom the officers openly said that the sailors were

completely revolutionaries.… So it is everywhere in Kronstadt.”

In November 1916 the Russian defences claimed their greatest

victory. A force of eleven German destroyers became entangled in minefields

while hunting coastal traffic and within forty-eight hours seven were lost and

one severely damaged. There was no Russian shipping in the area as they had

intercepted radio transmissions and stayed away.

Boredom and lack of activity were not the only reasons for

the men’s increased disillusionment with the war and the regime. Service in the

navy demanded a different sort of recruit to those of the army. The literacy

rate amongst sailors was approaching seventy-five per cent, (in the army it was

less than thirty per cent) a higher standard of proficiency with technology was

vital as were teamwork and initiative, all qualities which fostered a more

highly skilled and integrated body of men. The close proximity to urban,

industrial centres inevitably led them to be exposed to extreme political viewpoints

and the discussion of conditions ashore. Consequently when the revolution came

in March 1917 the sailors of the Baltic Fleet were ready and willing to

participate.

The Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet (Admiral A. A. Eberhardt) followed a more

aggressive policy, mounting operations against the Bosporus on 28 March 1915 and

again the next month in support of the Gallipolli expedition. By way of drawing

the Turks attention to the Black Sea coastline pretence was made of

reconnoitring the shore for possible landing sites as had been agreed with the

Western Allies. The Anatolian coastline slowly came to be dominated by the

Russians which forced the Turks to rely more and more on the slower overland

route to supply men and munitions for their Caucasian Front. When Bulgaria

entered the war several raids were made against coastal shipping but the

presence of German submarines limited such operations. However, it was in

support of the right flank of the Caucasian Front that the Black Sea Fleet made

its strongest contribution.

In August 1916 Kolchak was appointed commander of the Black

Sea Fleet. In November the Black Sea Fleet suffered its greatest loss, the

newly completed battleship Emperatritsa Mariia which blew up in Sebastopol

harbour with over 400 casualties. For the remainder of the war the Black Sea

virtually became a Russian lake and increasing use was made of the navy to

ferry and escort supplies to the army. The reasons noted for the decline of the

Baltic Fleet were much less pronounced amongst the Black Sea sailors. The

simple fact that the men were more or less continually involved in an active

war and were not subject to urban influences to the same extent as in the

Baltic saved the Black Sea Fleet from the worst excesses of the March Revolution.

Kolchak took many of his ships to sea when the situation in Petrograd became

serious and only returned to harbour when the Tsar had abdicated. Thus, when

dozens of officers of all ranks in the Baltic Fleet were being murdered by

their men the Black Sea Fleet remained comparatively quiet.

The navy and the revolutions

The speed with which the Baltic Fleet’s sailors responded to

the March events in Petrograd points to a sense of unity of purpose, although

not necessarily a carefully tailored uprising guided by a single mind. When the

revolution began the sailors supported it from the outset and were prepared to

shoot any who stood in their way. This included their officers, although many

were also killed as retribution for past behaviour. On 16 March Admiral A. I.

Nepenin, commanding the Baltic Fleet, informed the Provisional Government, “The

Baltic Fleet as a military force no longer exists.” As far as he could see his

ice bound ships had raised red flags.

In both fleets committees were established with powers

similar to those in the army. The difference between the fleets was Baltic Fleet’s

greater degree of militancy and involvement with the affairs of Petrograd.

During the July Days Baltic Fleet sailors were heavily involved but the actions

subsequently launched to contain radicalism seem to have achieved little but

the further alienation of the men. Despite this the sailors supported Kerensky

during the Kornilov affair but by the end of September the Provisional

Government exercised very little authority over them.