A special rehabilitation area for Army Group South was to be

established near Dnieperopetrovsk, while for Army Group Center similar areas

could be set up near Orsha, Minsk, Gomel, and Bryansk. Those few units of Army

Group North which were to be rehabilitated would probably be transferred to the

Zone of Interior. Rehabilitation was to begin in mid-March at the latest. After

the muddy season the fully rehabilitated units of Army Group Center were to be

transferred to Army Group South.

The exigencies of the last few months had led to the

commitment of a great number of technical specialists as infantrymen. The

overall personnel situation and the shortage of technically trained men made it

imperative either to return all specialists to their proper assignment or to

use them as cadres for newly activated units. The future combat efficiency of

the Army would depend upon the effective enforcement of this policy.

The high rate of materiel attrition and the limited capacity

of the armament industry were compelling reasons for keeping weapons and

equipment losses at a minimum.

In the implementing order to the army groups and armies, the

Organization Division of the Army High Command directed on 18th February that

those mobile divisions that were to be fully rehabilitated would be issued

50-60 percent of their prescribed motor vehicle allowance and infantry

divisions up to 50 percent. Every infantry company was to be issued four

automatic rifles and four carbines with telescopic sights; armor-piercing rifle

grenades were to be introduced. Bimonthly reports on manpower and equipment

shortages as well as on current training and rehabilitation of units were to be

submitted by all headquarters concerned.

The element of surprise was essential to the success of the

summer offensive. On 12th February Keitel therefore issued the first directive

for deceiving the Russians about future German intentions. The following

information was to be played into Soviet intelligence hands by German

counterintelligence agents:

At the end of the muddy season the German military leaders

Intended to launch a new offensive against Moscow. For this purpose they wanted

to concentrate strong forces by moving newly activated divisions to the Russian

theater and exchanging battle-weary ones in the East for fresh ones from the

West. After the capture of Moscow the Germans planned to advance to the middle

Volga and seize the industrial installations in that region.

The assembly of forces was to take place in secret. For this

purpose the capacity of the railroads was to be raised before the divisions

were transferred from the West. German and allied forces would meanwhile launch

a major deceptive attack in the direction of Rostov.

As to Leningrad, the prevailing opinion was that this city

would perish by itself as soon as the ice on Lake Ladoga had melted. Then the

Russians would have to dismount the railroad and the inhabitants would again be

Isolated. To attack in this area appeared unnecessary.

In addition, those German troops that were earmarked for the

Russian theater and presently stationed in the West were to be deceived by the

issuance of military maps and geographic data pertaining to the Moscow area.

The units that were already in the theater were not to be given any deceptive

information until the current defensive battles had been concluded. The same

directive also requested the Army and Luftwaffe to submit suggestions for other

deceptive measures. The maintenance of secrecy was strongly emphasized.

THE NAVY’S ROLE: FEBRUARY 1942

The German Navy’s principal concern in the Black Sea area

was the transportation of supplies for the Army. The difficulties were caused

by the shortage of shipping space and the absence of escort and combat vessels.

Measures taken to improve the German position in the Black Sea included

transfer of PT boats, Italian antisubmarine vessels, small submarines, and

landing craft; mine fields were also being laid. Orders had been issued to

speed up these measures and support the Army by bringing up supplies. Russian

naval forces in the Black Sea would have to be attacked and destroyed. The

degree of success obtained would determine the outcome of the war in the Black

Sea area. Attention was called to the fact that eventually it would become

necessary to occupy all Russian Black Sea bases and ports.

On the other hand, the remainder of the Russian Baltic fleet

stationed in and around Leningrad had neither strategic nor tactical value.

Ammunition and fuel supplies were exceedingly low. About 12 of the high speed

mine sweepers had been sunk so far, so that only four or five were left. About

65 out of 100 submarines had been sunk by the Germans.

THE INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE: 20th FEBRUARY 1942

In a summary dated 20th February 1942 the Eastern

Intelligence Division of the Army High Command stated that the Russians were

anticipating a German offensive directed against the Caucasus and the oil wells

in that area. As a countermeasure the Red Army would have the choice between a

spoiling offensive and a strategic withdrawal. Assuming the Russians would

attack, it was estimated that their offensive would take place in the south.

There they could interfere with German attack preparations, reoccupy

economically valuable areas, and land far to the rear of the German lines along

the Black Sea coast. If they were sufficiently strong, the Soviets would also

attempt to tie down German forces by a series of local attacks in the Moscow

and Leningrad sectors.

Numerous reports from German agents in Soviet-held territory

indicated that the Red Army had been planning the recapture of the Ukraine for

some time. At the earliest the Russian attack could take place immediately

after the muddy season, i. e. at the beginning of May.

The Russian forces identified opposite Army Group South

consisted of 83 infantry divisions and 12 infantry brigades as well as 20

cavalry divisions and 19 armored brigades, plus an unknown number of newly

organized units.

Interference from British forces seemed unlikely. The latter

would move into the Caucasus area only if their supply lines could be properly

secured, a time-consuming process that had not even been initiated. On the

other hand, lend-lease materiel was arriving in considerable quantities; the

first U. S. fighter planes had been encountered along the German Sixth Army

front.

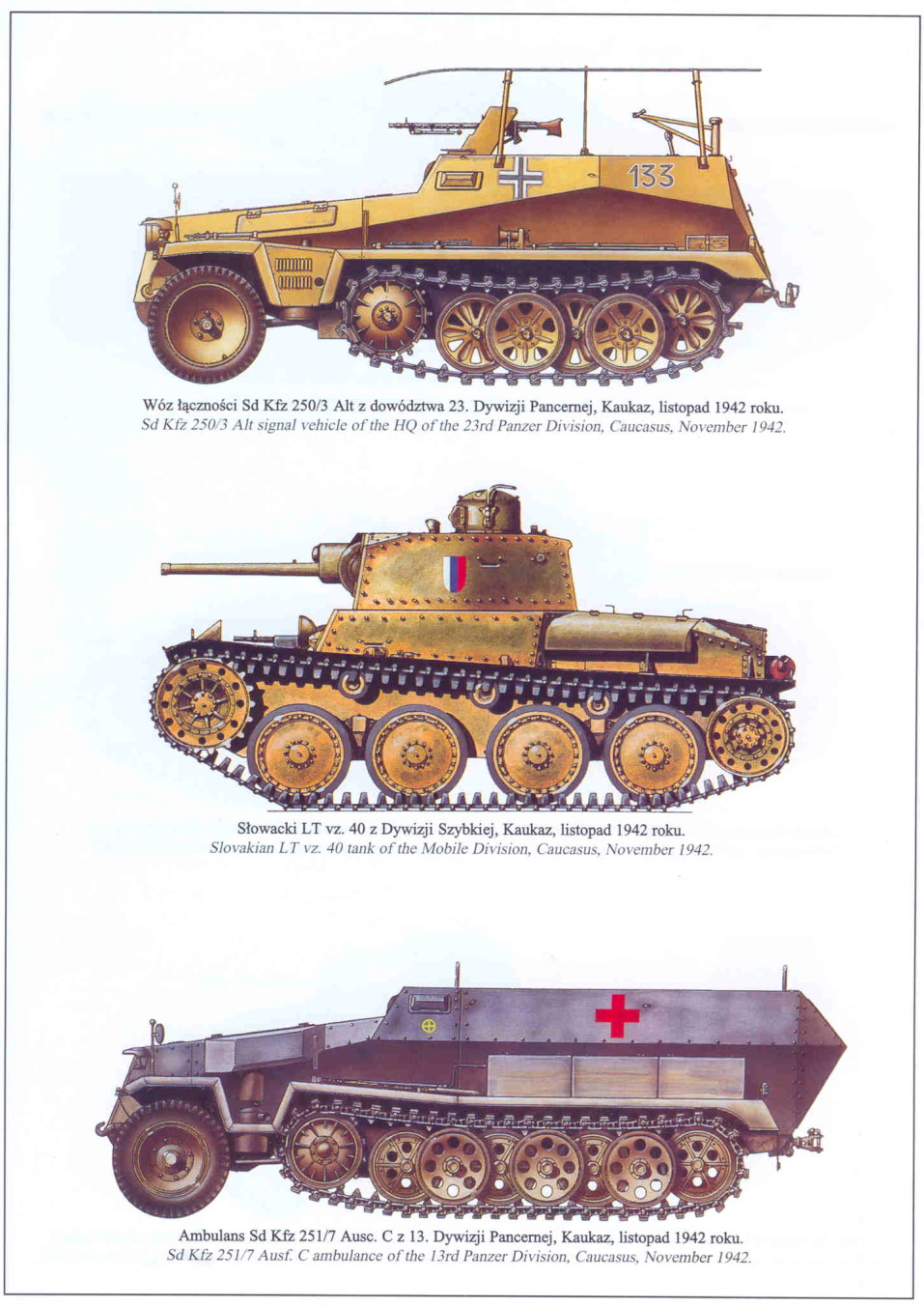

Caucasus Campaign (22 July 1942-February 1943)

German campaign, dubbed Operation EDELWEISS, to capture the

rich Caspian oil fields. Although the offensive was unsuccessful, the territory

taken in this operation represent- ed the farthest points to the east and south

reached by the German army during the war.

The great German summer offensive, Operation BLAU (BLUE),

opened on 28 June. General Erich von Manstein had argued for a concentration in

the center of the front. He believed that Soviet leader Josef Stalin would

commit all available resources to save Moscow and that this approach offered

the best chance of destroying the Red Army; it would also result in a more

compact front. Adolf Hitler rejected this sound approach and instead divided

his resources. In the north, he would push to take Leningrad, still under

siege, and link up with the Finns. But the main effort would be Operation BLAU

to the south, in which the Caucasus oil fields located near the cities of Baku,

Maikop, and Grozny would be the ultimate prize. Securing these areas would

severely cripple Soviet military operations, while at the same time aiding

those of Germany.

Hitler ordered Field Marshal Fedor von Bock’s Army Group

South to move east from around Kursk and take Voronezh, which fell to the

Germans on 6 July. Hitler then reorganized his southern forces into Army Groups

A and B. Field Marshal Siegmund List commanded Army Group A, the southern

formation; General Maximilian von Weichs had charge of the northern formation,

Army Group B.

Hitler’s original plan was for Army Groups A and B to cooperate

in a great effort to secure the Don and Donets Val- leys and capture the cities

of Rostov and Stalingrad. The two could then move southeast to take the oil

fields. The Germans expected to be aided in their efforts there by the fact

that most of the region was inhabited by non-Russian nationalities, such as the

Chechens, whose loyalty to the Soviet government was suspect.

On 13 July, Hitler ordered a change of plans, now demanding

that Stalingrad, a major industrial center and key crossing point on the Volga

River, and the Caucasus be captured simultaneously. This demand placed further

strains on already inadequate German resources, especially logistical support.

The twin objectives also meant that a gap would inevitably appear between the

two German army groups, enabling most Soviet troops caught in the Don River

bend to escape eastward.

On 22 July, Army Group A’s First Panzer and Seventeenth

Armies assaulted Rostov. Within two days, they had captured the city. A few

days later, the Germans established a bridgehead across the Don River at

Bataysk, and Hitler then issued Führer Directive 45, initiating EDELWEISS. He

believed that the Red Army was close to defeat and that the advance into the

Caucasus should proceed without waiting until the Don was cleared and

Stalingrad had fallen. The operation would be a case of strategic overreach.

Securing the mountain passes of the Caucasus region between

the Black and Caspian Seas was crucial in any operation to take the oil fields.

To accomplish this task, Army Group A had special troops trained for Alpine

operations, including Seventeenth Army’s XLIX Mountain Corps. Supporting Army

Group A’s eastern flank was Army Group B’s Fourth Panzer Army.

At the end of July, List had at his disposal 10 infantry divisions

as well as 3 Panzer and 2 motorized divisions, along with a half dozen Romanian

and Slovak divisions. Hitler expected List to conquer an area the size of

France with this force. Despite these scant German and allied forces, the Soviets

had only scattered units available to oppose the German advance. On 28 July,

the Soviets created the North Caucasus Front, commanded by Marshal Semen

Budenny, and Stalin ordered his forces to stand in place and not retreat. But

even reprisals failed to stem the Soviet withdrawal before Army Group A’s rapid

advance, which had all the characteristics of a blitzkrieg. Indeed, the chief

obstacles to the German advance were logistical, created by the vast distances

involved and terrain problems. The Germans used aerial resupply where possible

and also horses and camels to press their advance.

By 9 August, the 5th SS Panzer Division had taken the first

of the Caucasus oil fields at Maykop. To the west, infantry and mountain

formations of the Seventeenth Army had made slower progress, but on 9 August,

they took Krasnodar, capital of the rich agricultural Kuban region. They then

moved in a broad advance into the Caucasus Mountains, with the goal of taking

the Black Sea ports of Novorossiysk, Tuapse, and Sukhumi. Soviet forces, meanwhile,

continued to fall back into the Caucasus. As Budenny’s North Caucasus Front

prepared to defend the Black Sea ports, the Soviets sabotaged the oil fields,

removing much of the equipment and destroying the wellheads. So successful was

this effort that there would be no significant oil production from the region

until after the war.

SOVIET THERMOPYLAE: THE PROLETARY CEMENT FACTORY, 8/9

SEPTEMBER 1942

After the German 73. Infanterie-Division captured

central Novorossiysk, Ruoff ordered Wetzel’s V Armeekorps to continue the

advance along the coast road to threaten Tuapse from the west. The Soviet 47th

Army had been virtually demolished in the fight for the city and the only

significant Soviet force blocking the coast road was three battalions of naval

infantrymen, formed from survivors of Gorshkov’s Azov Flotilla and the 83rd

Naval Infantry Brigade. On 8/9 September, the German Infanterie-Regiment 213

began the effort to push along the coast road, supported by assault guns and

heavy artillery.

The 16th Naval Infantry Battalion had occupied a

strong position in the Proletary Cement Factory, on the outskirts of the town,

while the other two battalions were in the nearby Krasny Oktyabr Factory. Like

Thermopylae in ancient Greece, the terrain was narrow here due to the water of

Tsemes Bay and the nearby mountains, which reduced the German numerical

advantage. At dawn on 8 September, the German Landser from Infanterie-Regiment

213 came on at the point of the bayonet, but encountered unexpectedly strong

resistance at the Cement Factory. German infantrymen fought their way into the

lower floors and engaged in hand-to-hand combat, while Soviet sailors fired

down upon them from upper floors. After a day of intense fighting, the Soviet

battalion was nearly surrounded, but the survivors were able to slip out to

continue the fight at the Oktyabr Factory. Despite repeated attacks, the German

V Armeekorps could not achieve a breakthrough along the coast road and the

costly Soviet defence ultimately proved successful.

This scene shows the side of the factory and the

oncoming German infantry. Several of the Germans have already become casualties,

but a few of the Germans have reached the lower floor and are engaged in

vicious hand-to-hand combat with the Soviet naval infantrymen.

By the end of August, the German advance had slowed to a

crawl. For the Seventeenth Army, the problems were terrain and a stiffening

Soviet resistance. Bitter fighting occurred in Novorossiysk, beginning on 18

August when the Germans threw six divisions against the city. It fell on 6 September,

although the Soviets managed to evacuate their defending marine infantry by

sea.

To the east, the advance of the First Panzer Army, pushing

toward the oil fields at Grozny, also slowed. Problems there were largely

logistical, with a serious shortage of fuel impeding forward movement. In

addition, Hitler was gradually siphoning off First Army’s strength, including

two divisions, some of its artillery, and most of its air support (diverted

north to the cauldron of Stalingrad). Weather now became a factor, with the

first snowfall in the mountains on 12 September. Displeased with the progress

of his forces in the Caucasus and despite List’s objections, Hitler assumed

personal control of Army Group A on 10 September and sacked List.

Hitler’s plan was far too ambitious for the assets committed.

The weather had become a critical concern, as did continuing German logistical

problems. The Soviets, meanwhile, were able to feed additional resources into

the fight. On 14 October, the Germans suspended offensive operations in the

Caucasus, except for the Seventeenth Army efforts on the Terek River and around

Tuapse. The Germans took Tuapse several days later but then called a halt to

offensive operations on 4 November.

Events at Stalingrad now took precedence. By the end of

November, Soviets forces had encircled the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, and

Soviet successes there placed the Axis forces in the Caucasus in an untenable

situation. Then, on 29 November, the Soviet Transcaucasus Front launched an

offensive of its own along the Terek. The Germans repulsed this attack, but on

22 December, German forces began a withdrawal from positions along the Terek

River. At the end of December, with the situation to the north growing more

precarious daily, Hitler reluctantly ordered Army Group A to withdraw. This

movement began in early January, with Soviet forces unable seriously to disrupt

it. By early February, German forces had withdrawn to the Taman Peninsula, from

which Hitler hoped to renew his Caucasus offensive in the spring. In October

1943, however, German forces there were withdrawn across Kerch Strait into the

Crimea.

Germany’s Caucasus Campaign turned out to be a costly and

unsuccessful gamble. Ultimately, by splitting his resources between Stalingrad

and the Caucasus, Hitler got neither.