Greece and Its Colonies in the Archaic Age. Impelled by overpopulation and poverty, Greeks spread out from their homelands during the Archaic Age, establishing colonies in many parts of the Mediterranean. The colonies were independent city-states that traded with the older Greek city-states.

In the eighth century B. C., Greek civilization burst forth

with new energies, beginning the period that historians have called the Archaic

Age of Greece. Two major developments stand out in this era: the evolution of

the polis, or city-state, as the central institution in Greek life and the

Greeks’ colonization of the Mediterranean and Black seas.

The Polis

The Greek polis (plural, poleis) developed slowly during the

Dark Age but by the eighth century B. C. had emerged as a unique and

fundamental institution in Greek society. In a physical sense, the polis

encompassed a town or city or even a village and its surrounding countryside.

But the town or city or village served as the focus or central point where the

citizens of the polis could assemble for political, social, and religious

activities. In some poleis, this central meeting point was a hill, which could

serve as a place of refuge during an attack and later in some locales came to

be the religious center where temples and public monuments were erected. Below

this acropolis would be an agora, an open space that served both as a place

where citizens could assemble and as a market.

Poleis varied greatly in size, from a few square miles to a

few hundred square miles. The larger ones were the product of consolidation.

The territory of Attica, for example, had once had twelve poleis but eventually

be- came a single polis (Athens) through a process of amalgamation. The

population of Athens grew to about 250,000 by the fifth century B. C. Most

poleis were much smaller, consisting of only a few hundred to several thousand

people.

Although our word politics is derived from the Greek term

polis, the polis itself was much more than just a political institution. It

was, above all, a community of citizens in which all political, economic,

social, cultural, and religious activities were focused. As a community, the

polis consisted of citizens with political rights (adult males), citizens with

no political rights (women and children), and noncitizens (slaves and resident

aliens). All citizens of a polis possessed rights, but these rights were

coupled with responsibilities. The Greek philosopher Aristotle argued that the

citizen did not belong just to himself: “We must rather regard every citizen

as belonging to the state.” The unity of citizens was important and often

meant that states would take an active role in directing the patterns of life.

The loyalty that citizens had to their poleis also had a negative side,

however. Poleis distrusted one another, and the division of Greece into fiercely

patriotic sovereign units helped bring about its ruin. Greece was not a united

country but a geographic location. The cultural unity of the Greeks did not

mean much politically.

A New Military System: The Greek Way of War

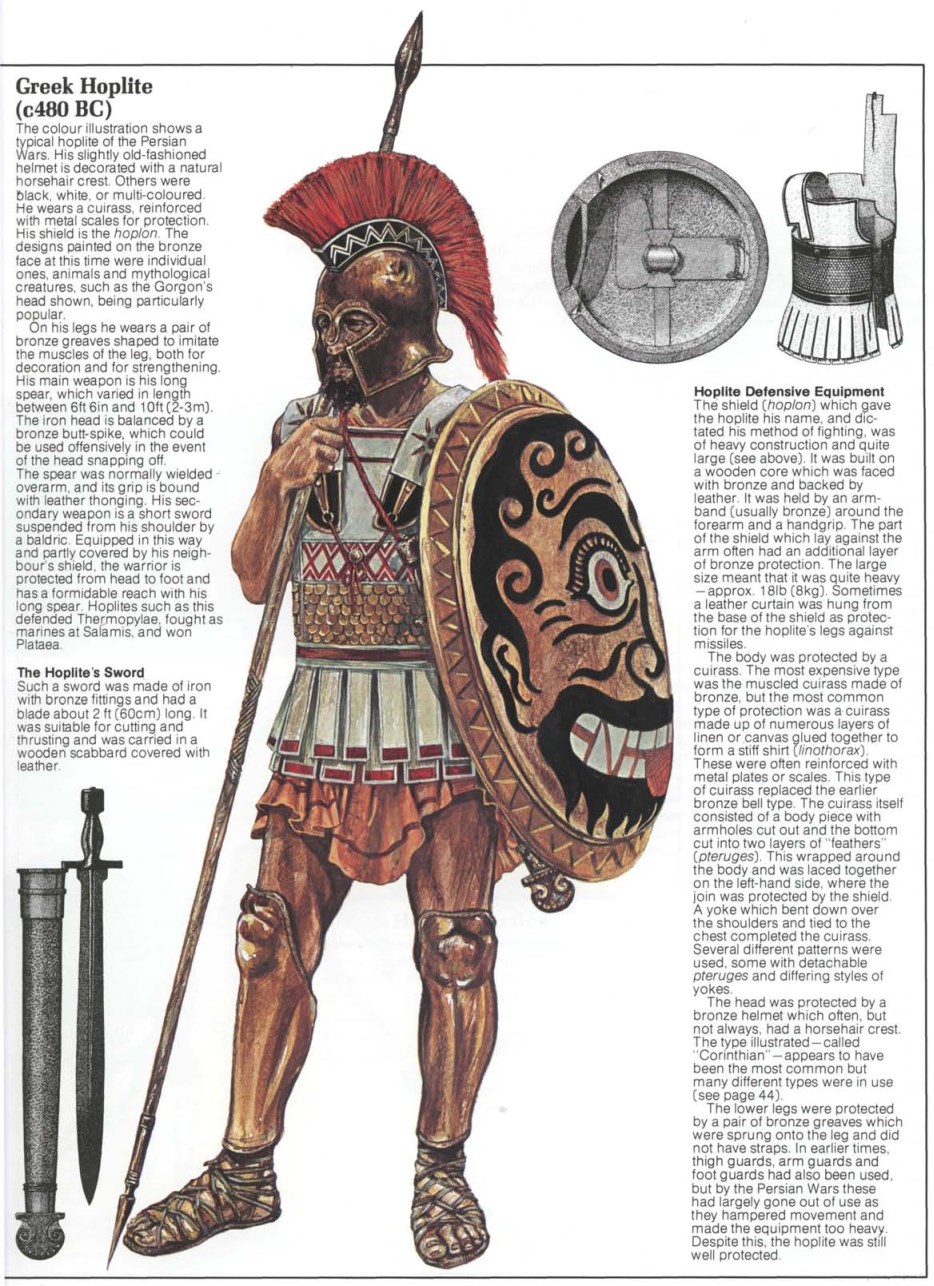

As the polis developed, so did a new military system. In

earlier times, wars in Greece had been fought by aristocratic cavalry

soldiers—nobles on horseback. These aristocrats, who were large landowners,

also dominated the political life of their poleis. But at the end of the eighth

century, a new military order came into being that was based on hoplites,

heavily armed infantrymen who wore bronze or leather helmets, breastplates, and

greaves (shin guards). Each carried a round shield, a short sword, and a

thrusting spear about 9 feet long. Hoplites advanced into battle as a unit,

shoulder to shoulder, forming a phalanx (a rectangular formation) in tight

order, usually eight ranks deep. As long as the hoplites kept their order, were

not outflanked, and did not break, they either secured victory or, at the very

least, suffered no harm. The phalanx was easily routed, however, if it broke

its order. The safety of the phalanx thus depended on the solidarity and

discipline of its members. As one seventh-century B. C. poet observed, a good

hoplite was “a short man firmly placed upon his legs, with a courageous heart,

not to be uprooted from the spot where he plants his legs.”

The hoplite force, which apparently developed first in the

Peloponnesus, had political as well as military re- percussions. The

aristocratic cavalry was now outdated. Since each hoplite provided his own armor,

men of property, both aristocrats and small farmers, made up the new phalanx.

Initially, this created a bond between the aristocrats and peasants, which

minimized class conflict and enabled the aristocrats to dominate their

societies. In the long run, however, those who could become hoplites and fight

for the state could also challenge aristocratic control.

In the new world of the Greek city-states, war became an

integral part of the Greek way of life. The Greek philosopher Plato described

war as “always existing by nature between every Greek city-state.” The Greeks

created a tradition of warfare that became a prominent element of Western

civilization. The Greek way of war exhibited a number of prominent features.

The Greeks possessed excellent weapons and body armor, making effective use of

technological improvements. Greek armies included a wide number of

citizen-soldiers, who gladly accepted the need for training and discipline,

giving them an edge over their opponents’ often far-larger armies of

mercenaries. Moreover, the Greeks displayed a willingness to engage the enemy

head-on, thus deciding a battle quickly and with as few casualties as possible.

Finally, the Greeks demonstrated the effectiveness of heavy infantry in

determining the outcome of a battle. All of these features of Greek warfare

remained part of Western warfare for centuries.

Colonization and the Growth of Trade

Greek expansion overseas was another major development of

the Archaic Age. Between 750 and 550 B. C., large numbers of Greeks left their

homeland to settle in distant lands. Poverty and land hunger created by the

growing gulf between rich and poor, overpopulation, and the development of

trade were all factors that led to the establishment of colonies. Some Greek

colonies were sim- ply trading posts or centers for the transshipment of goods

to Greece. Most were larger settlements that included good agricultural land

taken from the native populations found in those areas. Each colony was founded

as a polis and was usually independent of the mother polis (metropolis) that

had established it.

In the western Mediterranean, new Greek settlements were

established along the coastline of southern Italy, including the cities of

Tarentum (Taranto) and Neapolis (Naples). So many Greek communities were

established in southern Italy that the Romans later called it Magna Graecia

(“Great Greece”). An important city was founded at Syracuse in eastern Sicily

in 734 B. C. by the city-state of Corinth, one of the most active Greek states

in establishing colonies. Greek settlements were also established in southern

France (Massilia—modern Marseilles), eastern Spain, and northern Africa west

of Egypt.

To the north, the Greeks set up colonies in Thrace, where

they sought good agricultural lands to grow grains. Greeks also settled along

the shores of the Black Sea and secured the approaches to it with cities on the

Hellespont and Bosporus, most notably Byzantium, site of the later

Constantinople (Istanbul). A trading post was established in Egypt, giving the

Greeks access to both the products and the advanced culture of the East.

The Effects of Colonization

The establishment of these settlements over such a wide area

had important effects. For one thing, they contributed to the diffusion of

Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean basin. The later Romans had their

first contacts with the Greeks through the settlements in southern Italy.

Furthermore, colo- nization helped the Greeks foster a greater sense of Greek identity.

Before the eighth century, Greek communities were mostly isolated from one

another, leaving many neighboring states on unfriendly terms. Once Greeks from

different communities went abroad and encountered peoples with different

languages and customs, they became more aware of their own linguistic and

cultural similarities.

Colonization also led to increased trade and industry. The

Greeks sent their pottery, wine, and olive oil to these areas; in return, they

received grains and metals from the west and fish, timber, wheat, metals, and

slaves from the Black Sea region. The expansion of trade and industry created a

new group of rich men in many poleis who desired political privileges

commensurate with their wealth but found them impossible to gain because of the

power of the ruling aristocrats. The desire for change on the part of this

group soon led to political crisis in many Greek states.

Tyranny in the Greek Polis

When the polis emerged as an important institution in Greece

in the eighth century, monarchical power waned, and kings virtually disappeared

in most Greek states or survived only as ceremonial figures with little or no

real power. Instead, political power passed into the hands of local

aristocracies. But increasing divisions between rich and poor and the

aspirations of newly rising industrial and commercial groups in Greek poleis

opened the door to the rise of tyrants in the seventh and sixth centuries B. C.

They were not necessarily oppressive or wicked, as our word tyrant connotes.

Greek tyrants were rulers who seized power by force and who were not subject to

the law. Support for the tyrants came from the new rich, who made their money

in trade and industry, as well as from poor peasants, who were in debt to

landholding aristo- crats. Both groups were opposed to the domination of

political power by aristocratic oligarchies.

Tyrants usually achieved power by a local coup d’e’tat and maintained it by using mercenary soldiers. Once in power, they built new marketplaces, temples, and walls that created jobs, glorified the city, and also enhanced their own popularity. Tyrants also favored the interests of merchants and traders by encouraging the founding of new colonies, developing new coinage, and establishing new systems of weights and measures. In many instances, they added to the prosperity of their cities. By their patronage of the arts, they encouraged cultural development.

The Example of Corinth

One of the most famous examples of tyranny can be found in

Corinth. During the eighth and early seventh centuries B. C., Corinth had become

one of the most prosperous states in Greece under the rule of an oligarchy led

by members of the Bacchiad family. Their violent activities, however, made them

unpopular and led Cypselus, a member of the family, to overthrow the oligarchy

and assume sole control of Corinth.

Cypselus was so well liked that he could rule without a

bodyguard. During his tyranny, Corinth prospered by exporting vast quantities

of pottery and founding new colonies to expand its trade empire. Cypselus’ son,

Periander, took control of Corinth after his father’s death but ruled with such

cruelty that shortly after his death in 585 B. C., his own son, who succeeded

him, was killed, and a new oligarchy soon ruled Corinth.

As in Corinth, tyranny elsewhere in Greece was largely

extinguished by the end of the sixth century B. C. The children and

grandchildren of tyrants, who tended to be corrupted by their inherited power

and wealth, often became cruel and unjust rulers, making tyranny no longer seem

such a desirable institution. Its very nature as a system outside the law

seemed contradictory to the ideal of law in a Greek community. Tyranny did not

last, but it played a significant role in the evolution of Greek history. The

rule of narrow aristocratic oligarchies was destroyed. Once the tyrants were

eliminated, the door was opened to the participation of more people in the affairs

of the community. Although this trend culminated in the development of

democracy in some communities, in other states expanded oligarchies of one kind

or an- other managed to remain in power. Greek states exhibited considerable

variety in their governmental structures; this can perhaps best be seen by the axiomatic

socialites of the two most famous and most powerful Greek city-states, Sparta

and Athens.