Battle of Barcelona, (1705; War of the Spanish Succession) An Anglo-Dutch force had taken Gibraltar (1704) and from there a fleet under Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell landed a force of 6,000 British soldiers, under the Earl of Peterborough, north of Barcelona (August 1705). This force took the hill of Montjuich, south of the city, which led to the surrender of the city (9 October). Archduke Charles (later Charles VI of the Holy Roman Empire) was proclaimed King Charles III of Spain.

Peterborough, Earl of (1658-1735) Born Charles

Mordaunt, he spent a short time at university and then served in the navy,

largely in the Mediterranean under his uncle, Henry, who was a vice-admiral. He

inherited the title of Viscount Mordaunt (1675). Mordaunt returned home (1680)

and supported William of Orange, from whom he received many preferments when

William became king (1689). He was involved in various intrigues, quarrelling

with Marlborough and Godolphin. He became Earl of Peterborough (1697) on the

death of his uncle. In 1705 he was given command of the army sent to Spain and

undertook the siege of Barcelona, for which he claimed all the credit. Mordaunt

was then given full powers of civil administration by the recently crowned King

Charles of Spain and moved to Valencia where he stayed despite various other

upheavals throughout Spain. He was ordered by Queen Anne to leave Spain for

Italy. The rest of his command in Spain was glad to see him go. He sailed for

Genoa. He returned to Valencia (1706) but was recalled to England (1707) where

he was indicted for his dilatory conduct in Spain and Italy. The case became a

power struggle between Mordaunt and Marlborough, and as Marlborough was out of

favour Mordaunt was acquitted. He was made ambassador- extraordinary to Vienna

(1711), where he incurred further displeasure. He returned to England (1712)

and was made colonel of the Royal Horse Guards (Blues and Royals) of which post

he was deprived (1715) on the accession of George I. He held no further

military appointments of importance and spent the rest of his life in intrigue

at home and on the Continent.

Most will have some familiarity with the campaigns and great

battles of John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough. Fewer may have the same

knowledge of the campaigns conducted in the Iberian Peninsula during the course

of the War of the Spanish Succession by Charles, Third Earl of Peterborough in

the years 1705 and 1706.

The Earl and his small force, bolstered by timid allies,

were constantly opposed by superior numbers yet managed to record a number of

decisive victories in small encounters, larger battles and sieges. And all in

under two years! At the end of his brief campaign the Earl left Spain, and

within one further year all his successes were rendered pointless at the Battle

of Almanza on 25th April, 1707, when Allied forces were defeated heavily by

Marshal Berwick.

The Opening Phase

The early actions in this theatre were naval. On October

12th, 1702 Sir George Rooke forced the boom of the harbour of Vigo with his

fleet of thirty British and twenty Dutch warships to destroy the French and Spanish

fleets at anchor. He burned eleven men-of-war and captured a further ten. He

also took as prizes eleven Spanish treasure galleons with their cargoes intact.

On July 24th, 1704 Rooke was again in action leading a

combined British and Dutch fleet in the capture of the fortress of Gibraltar

from the Spanish garrison under the Marquis de Salinas. The fortress resisted

for a mere two days and Britain acquired the ‘rock’ for its naval power for the

loss of only twelve officers and two hundred and seventy-six men killed or

wounded. Apart from Rooke’s victories there was little other early success for

the Allies facing the Duke of Berwick, the natural son of James II and

Arabella, the sister of the Earl of Marlborough.

The Earl’s Campaign, 1705

Towards the end of May 1705 the Earl sailed from St Helen’s

with a force of some 5,000 men, arriving in Lisbon on 20th June Here, besides

taking on stores, he exchanged with the Earl of Galway two newly raised

regiments of Foot for Dragoons. On 28th June the Earl sailed from Lisbon

instructed “. . . vigorous push in Spain. . .” and began his campaign

by laying siege to Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia.

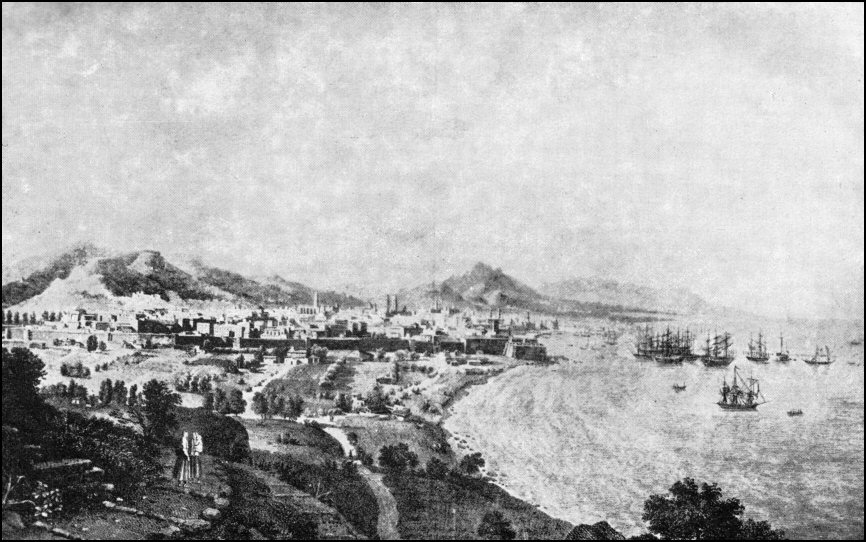

On 16th August 1705 the Earl’s small force anchored in the

Bay of Barcelona, after having paused on route to seize the to make a fortress

of Denia at the mouth of the Guadalquivir. The siege of Barcelona was rendered

more difficult by the presence, a mile inland, of the fortress of Monjuick.

This fortress dominated the landward approaches to the city and must first be

taken by any enemy wishing to invest the city. The Earl’s timid ally, the

Archduke Charles of Austria, was unenthusiastic about the prospects of success

and so the siege did not open until 14th September.

The Earl, with only one aide, reconnoitred the fortress and,

noting the laxity of the garrison, decided upon a surprise assault. Feigning

the withdrawal of his artillery, Peterborough personally led a night march by

1,800 of his force upon the defences of the fortress. In three columns they

made a dawn attack, carrying the outer works and ramparts under heavy fire. On

hearing of a strong relief force from the city the attack began to falter and

the early initiative was nearly lost. The Earl himself mounted the ramparts

and, seizing a standard, rallied the attackers. Upon this renewed attack, the

Governor of the fortress, fearing a larger scale assault, withdrew his force

into the city’s defences. Peterborough’s forces then began to construct saps

against the city. Soon the walls were breached but, before the city could be

stormed, the Governor surrendered on 9th October. In this one action much of

the area of Catalonia was secured for Charles.

After the successes at Denia and Barcelona Charles insisted

that the army go into winter quarters. This gave time for the opposing forces

of Philip V of Spain to regroup and consider how to go on the offensive.

1706

Early in the spring of 1706 Philip’s forces besieged the small

garrison of 500 troops holding San Mateo. The siege was commanded by the

Marquis de las Torres with a force of some 4,000 Foot and 3,000 Horse.

Peterborough was sent to raise the siege with a force of only 1,200 men. Facing

such a daunting task the Earl resorted to a deception. He allowed the enemy to

capture a message to the Governor of San Mateo stating that a large force was

on hand to raise the siege. He then disposed his small force in the coppice and

brushwood screened heights above San Mateo with such skill that Torres thought

himself facing a far superior force and withdrew, raising the siege.

Peterborough was able to enter San Mateo in triumph without the necessity of

battle. He immediately decided to take the offensive and set off with a force

of 200 Horse to pursue Torres 7,000! By harassing stragglers and intercepting

messengers he was able to retain the initiative and keep the thought in his opponent’s

mind that a large force was closing on him. So effective was this pursuit that

Torres’ withdrawal became a headlong rout.

In the meantime the Duke of Arcos had besieged Valencia. The

Earl set off to its relief with his small force. Following the customs of the

day he began to entrench his force to threaten the besiegers. Negotiations were

opened with Arcos, who was tricked into believing that his supervising

engineer, general Mahony, was a traitor. Arcos arrested Mahony and raised the

siege while Mahony’s force disbanded. Again the Earl had succeeded in raising a

siege with a very inferior force. However, Torres and 4,000 men were marching

to reinvest Valencia with a heavy artillery train embarked at Alicante.

Peterborough’s superior intelligence gathering allowed both forces to be

intercepted, thus preventing the siege from being renewed.

Despite the reverses at Valencia, Philip’s forces began a

siege of Barcelona on 2nd April, 1706. With only 2,000 men the Earl set off to

raise the siege. However, the superior force of the enemy compelled his force

to remain on the heights above the city. The French reduced the fortress of

Monjuick and breached the city’s walls. With an assault expected at any time,

the Earl drew up a daring plan. By night he embarked his force in fishing boats

from Leyette and ordered the British supporting squadron to sea. The French

Admiral, fearing being trapped in the bay, ordered the French squadron to sea

way for the small boats and their troops to enter the city. Seeing the squadron

leave and the reinforcements entering the city the French were disheartened and

raised the siege.

Briefly now Madrid was occupied, but Peterborough was unable

to continue command whilst having the timid Archduke Charles for an ally. He

was succeeded in command by the Earl of Galway.

On 25th April, 1707 Galway’s force of 15,000 Allied British

and Portuguese troops, comprising twenty-five battalions of Foot, seventy-seven

squadrons of Horse and forty guns, at the Battle of Almansa. Galway lost 7,000

men and thirty guns, were defeated by Berwick’s 30,000 French and Spanish,

comprising seventy-two battalions of Foot, seventy-seven squadrons of Horse,

and twenty-four guns. All the hard-won advantages of the Earl of Peterborough’s

campaigns of the previous two years were lost.

Not until 27th July, 1710 did the Allies enjoy another major

victory, when James, Earl of Stanhope, and his force of 24,000 men defeated

Villaderia’s force of 22,000 men at the Battle of Almenara. The Spanish force

was only saved from total disaster by nightfall. On 10th August, 1710 Charles

defeated De Bay’s force of 20,000 French and Spanish at Zaragoza, taking 5,000 prisoners

and 36 guns. However, on 10th December, 1710 Stanhope’s force was ambushed at

Brihuega by Vendome’s force while retreating from Madrid to Barcelona. His

entire force was killed or taken prisoner, Stanhope himself being taken captive

along with his remaining 500 men. The following day, Vendome’s force defeated

Charles at Tillaviciosa, taking 2,000 prisoners and 22 guns.

One of the king’s commissioners to reform the army

Since many officers had a proprietary interest in their offices,

it is hardly surprising that some believed that those offices should produce a financial

return. Charles Mordaunt, first earl of Monmouth (and later third earl of

Peterborough), one of the king’s commissioners to reform the army, although

himself a gentleman officer rather than a professional, strongly disapproved of

the purchase system because `it disobliges all good officers that expect to

rise by their service and diligence’. Monmouth was surprised and shocked to

learn that there were two particular coffee-houses in London where colonels met

to broker commissions as if they were taking bids on a public stock exchange.

`They sell most scandalously to any man without the least pretence (against all

the just ones) that gives them the most money.’ Such officers did not submit

easily to military discipline, and Monmouth complained that they could not be

counted upon to embark with their regiments for Flanders. But, it must be

added, most people thought Monmouth was mad, and his was a minority voice.